Eastern Spirit, Western Mind: How to See the World Through Poetic Eyes

Parallels between the lives of Rainer Maria Rilke and Natsume Sōseki and their path to poetic genius.

A Russian historian Naum Kleiman, in one of his essays wrote that ‘all great artists in history always came in pairs — Da Vinci came with Michelangelo; Byron came with Shelley; Shostakovich came with Prokofiev.’

Kleiman’s statement can also be applied to books. There are books that also come in pairs such as George Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, or Dante’s Divine Comedy and Milton’s Paradise Lost.

It seems that the fate had paired the timeless Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke with the poetic novel Three Cornered World written by a Japanese author Natsume Sōseki.

The works of Rilke are well-known in the English speaking world, while those of Sōseki remain largely obscure. In his native Japan, however, Sōseki is considered as one of the greatest among the modern Japanese writers.

Rilke had never heard about his ‘pair’ and neither did Sōseki. They did not influence each other the way Da Vinci influenced Michelangelo or Byron influenced Shelley.

What unites and makes this pair unique is that their destinies mirrored each other, inspiring the creation of two exceptional books. Though their styles differ greatly, both offer hope for living a more fulfilling life.

In the autumn of 1902, Franz Xaver Kappus was sitting in the garden of the Military Academy in the Austrian city of Wiener Neustadt. He was so absorbed in reading that he barely noticed when one of his teachers approached him.

The teacher gently took the book from Kappus’s hands, looked at its title, and said:

“Poems by Rainer Maria Rilke? Our student René is a poet now?”

It turned out that Rilke — one of the most admired poets of the time and whose verse Kappus read so attentively — was once a student at the same Military Academy as Kappus.

Horaček — that was the name of the teacher — suggested that Kappus write a letter to Rilke and attach his own poems for review.

Kappus agreed with his suggestion and sent a letter with his poems to Rilke with almost no hope of ever getting a reply.

I. Art as an antidote to modernity

However, Rilke did reply, and in his first response he declined to review the poems that Kappus enclosed with his letter.

He said that all critical intentions are too far from him and that:

“…nothing can one approach a work of art so little as with critical words: they always come down to more or less happy misunderstandings”.

He urged Kappus to cease seeking approval of his verses from others.

“You ask whether your verses are good. You ask me. You have asked others before. You send them to magazines. I beg you to give up all that”.

Instead Rilke asked young Kappus to journey deeper inside his own soul to examine reasons that motivated him to write.

“You’re looking to the outside and that above all you should not be doing now. Nobody can advise you and help you, nobody. There is only one way. Go into yourself. Examine the reason that bids you to write; Check whether it reaches its roots into the deepest region of your heart, admit to yourself whether you would die if it should be denied you to write”.

At first glance Rilke’s advice doesn’t express any ideas that were not voiced by other poets before. Lord Byron famously said: ‘If I don’t write to empty my mind, I go mad’ — when he was asked his motivation for writing.

Rilke knew himself that the ideas which he wrote to Kappus were not original, but his aim was not originality, rather a description of how the poet sees at the world.

This is precisely what makes Rilke’s letters so unique. For the first time in literary history someone, perhaps unintentionally, gathered pieces of advice given by poets across the generations such as Sidney, Shelley, Shakespeare or Schiller in one place.

Whilst Rilke addressed his letters to Kappus, he knew that the ideas which he included would be useful to all aspiring artists. He particularly thought of those who refused to surrender their independent minds to mass-movements that were on the rise at the time. To become immune from the so-called ‘collective mind,’ one had to look at the world like a poet.

In the second letter, which Rilke wrote while residing in the Italian city of Pisa, he tells Kappus what precisely he means. Looking at the world like a poet means ‘to see beauty in every day and even mundane things’.

‘If your everyday life seems to lack material, do not blame it; blame yourself, tell yourself that you are not poet enough to summon up its riches, for there is no lack for him who creates and no poor, trivial place’

This idea was expressed before by John Milton in his epic poem Paradise Lost:

‘The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven..’

However, what neither Rilke nor Kappus could know, and couldn’t even suspect, was that thousands of miles away, a Japanese writer Natsume Sōseki was writing a novel that has a striking resemblance to Rilke’s advice.

II. One Muse, Two Poets

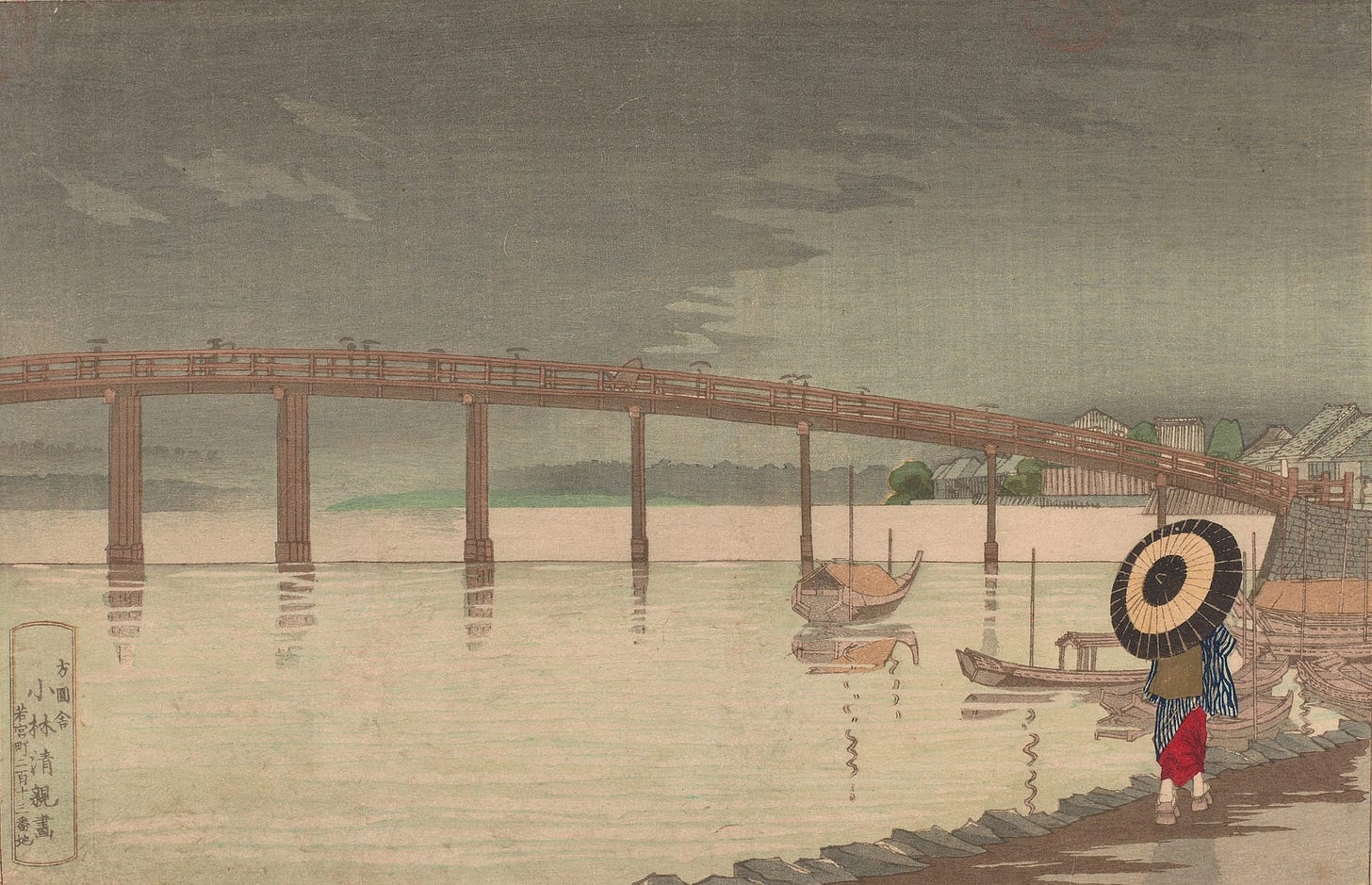

‘Three Cornered World’ by Natsume Sōseki was published in 1906 in Japan, exactly when the correspondence between Kappus and Rilke took place.

There is no evidence that Sōseki ever heard of Rilke or that he could have read the letters between the two, since ‘Letters to a Young Poet’ (how later publishers titled Rilke’s letters) was first published in Vienna two decades later in 1929.

Both works are remarkably similar not only by the ideas they express, but also by the motivations why they were written. It is, as if, the same Muse inspired them while their authors were thousands of miles apart.

Since the mid-19th Century, Japan was going through enormous economic and cultural transformations in an attempt to catch up with the West. For over two centuries Japan was closed to the outside world, which made it technologically backward in comparison to the Western powers.

When the American ships — led by the Commodore Matthew Perry — landed on its shores in 1848, the Japanese elite realized that it has no choice but to rapidly educate and modernize itself.

Thousands of scholars were sent abroad to study Western ideas with the purpose of bringing them back to Japan. Sōseki was one of them.

In 1900, he was sent to study in Great Britain to become the first ‘Japanese English literary scholar’.

Later in his writings Sōseki described his life in London as ‘the most unpleasant years in my life. Among English gentlemen I lived in misery, like a poor dog that had strayed among a pack of wolves.’

Initially, he was set to study at Cambridge, but the scholarship he received from the Japanese government was not enough to live on. So he settled to study at the University College London where it was more affordable.

Meredith McKinney writes in her introduction to ‘Three Cornered World’ that Sōseki spent ‘most of his days indoors buried in books, and his friends feared that he might be losing his mind.’

It was perhaps this experience of alienation, poverty and seclusion that inspired Soseki to write his novel. He also witnessed not only how technology distances humanity from the world of nature, but also how it distances people from each other.

‘The front of [steam train] has eyes like a giant snake, which will take young men to the abyss’ — he wrote later in a letter to his friend, describing how young Japanese soldiers were taken to the frontline in Russo-Japanese war by the steam trains, which were a newly imported technology from the West.

Rilke expresses the same fears as Sōseki in his semi-autobiographical ‘The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge’ where he describes his alienation from the modern Parisian society, whilst he resided there.

III. Eastern Spirit, Western Mind

When I was a student in Prague, back in 2010, I used to take those long walks across the city with no particular destination. In my early twenties I knew nothing about Rilke, but I passed the building where he was born every week.

These purposeless walks was sort of an exercise in meditation and contemplation about life. I had no schedule, no rush and no need to be anywhere at a certain time. I did not keep a diary — as I do right now — because my mind was not fixed on any particular problem or idea.

Reading Sōseki’s ‘Three Cornered World’ reminded me of those walks that I used to have. The story of this novel — like my long walks — has no precise destination. There are no plot twists or tension in it that will make your heart beat faster. There is no rush.

Instead, the story focuses on describing how to look at the world through the lense of a poet.

Sōseki wrote this novel, which is today considered to be a canon of Japanese literature, in a single week. Perhaps, it served as an antidote to the terrible experiences he had during his time in London and then upon arrival to Japan.

The character, from whose perspective the story is told, retreats to the mountains of Japan. He is a young aspiring artist who is in search of a scenery he could paint.

‘However you look at it, the human world is not an easy place to live. And when the difficulties intensify, you find yourself longing to leave the world and dwell in an easier one — and then, when at last you understand that difficulties will dog you wherever you may live, this is when poetry and art are born.

~ the first passage from ‘Three Cornered World’ by Nastsume Sōseki

What a eloquent passage to begin a novel with. There are books one should read with a pencil in hand to highlight beautiful passages, but Sōseki’s story is filled with so many beautiful passages, that its reader will run out of pencil before reaching the middle of the book.

The poetry and art are born when we realize that it is our only way to escape the ‘difficulties [that] will dog [us] wherever [we] may live’.

Sōseki continues:

‘Herein lies the poet’s true calling, the artist’s vocation. We owe our humble gratitude to all practitioners of the arts, for they mellow the harshness of our human world and enrich our human heart.’

This echoes the famous line by Nietzsche: ‘no one can build you the bridge on which you, and only you, must cross the river of life.’

For Sōseki, as well as for Rilke, it is poetry that acts like a bridge between the harshness of our world and the inherent beauty of our soul.

However, the difference between the two lies in the way they chose to describe how this metaphorical bridge should be built. For Sōseki this bridge is built from the way we should feel the world around us; whilst for Rilke it is built from the way we should think about the surrounding us world.

In one of his meditations Sōseki’s protagonist says that one can call himself an artist even if he hasn’t produced any works of art yet. Artist is not who creates art, but a person who has learnt how to see the beauty that’s hidden in the world.

‘Only by bringing myself to this unknown mountain village and steeping myself deep in its late spring world have I at last found within me the attitude of the pure artist. Once have I crossed this frontier, all the beauties of the world become mine.

I haven’t made a single painting since arriving…and you call yourself a painter? you may say with a sneer. But sneer you may, I am for the present a true artist, magnificent artist. Those who have attained this state don’t necessarily produce great works — but all who produce great works must first attain it.

Rilke expresses similar thoughts in his letter to Kappus which he sent from Rome:

To be an artist means: not to calculate or count; to grow and ripen like a tree which doesn’t hurry the flow of its sap and stands at ease in the spring gales without fearing that no summer may follow. It will come. But it only comes to those who are patient.

For both of them, becoming an artist was a way of survival in a callous and heartless world that they witnessed is coming forward. It was like an antidote required for the survival of their souls.

The first step that one should take towards becoming an artist is to retreat into a place where one can find solitude. That’s why Sōseki’s character retreats into the quite mountains, while Rilke writes to Kappus:

The necessary thing is after all but this: solitude, great inner solitude. Going-into oneself and for hours meeting no one — this one must be able to attain.

To be solitary, the way one was solitary as a child, when the grownups went around involved with things that seemed important and big because they themselves looked so busy and because one comprehended nothing of their doings.

Solitude is different from loneliness. Solitude is about enjoying your own company. Only a soul that is rich in experience can be comfortable with staying alone with itself.

Sōseki describes this in the second chapter when his character stops by a house located on the mountain side of a solitary old lady.

‘This old woman, who comprehends the swiftness of the turning wheel of Time as she counts off on bent fingers the passage of five years, must then surely be closer to the unworldly mountain immortals than to us humans.’

By living in close touch with nature and in solitude, the woman who Sōseki describes, is close to an artist in the way she looks at the world.

The connection with nature is also included in letters of Rilke, who emphasized that the Nature is in itself an act of creation.

Other than inner-self, solitude and nature — both works stress the importance of conquering our fears and sorrows.

‘If you see something frightening simply as what it is, there’s poetry in it; if you step back from your reactions and view something uncanny on its own terms, simply as an uncanny, there’s a painting there.’

~ Chapter 4, Three Cornered World, Nastume Sōseki.

While for Rilke ‘everything that terrifying is deep down a helpless thing that needs help,’

For an artist needs to come to terms with his fears as well as his sorrows, because ‘sorrows may be the poet’s unavoidable dark companion, but the spirit with which he listens to the skylark’s song holds not one jot of suffering’, as Sōseki’s character says while climbing the mountain.

Rilke urges us to ‘describe your sorrows and desires, passing thoughts and the belief in some sort of beauty — describe all these with loving, quiet, humble sincerity, and use, to express yourself’.

IV. Learning to see all over again

Albert Camus in his essay The Myth of Sisyphus wrote that:

Thinking is learning all over again to see, to be attentive, to focus consciousness; it is turning every idea and every image, in the manner of Proust, into a privileged moment.

In their works both Rilke and Sōseki taught their readers how to see, how to be more attentive and how to focus one’s consciousness in rapidly changing world. We still need that advice because the speed of that change has only increased in our time.

That’s why Three Cornered World influenced not only modern Japanese writers such as Yukio Mishima or Yasunari Kawabata, but also modern Western thinkers as Susan Sontag, Haruki Murakami, and even the greatest pianist of the 20th century — Glenn Gould.

Gould dedicated the last 15 years of his life re-reading and annotating Sōseki’s novel. It is said that on the day he died he had two books on his side — the Holy Bible and Three Cornered World.

Both books are very short — the Penguin edition of Rilke’s letters is only 50 pages long; while Sōseki’s novel spans just 140 pages — but they are being constantly re-read, annotated or discussed by artists and thinkers around the world to this day.

This article was originally published in March, 2021 on Medium.

I no longer write there, so thought I would share some of the pieces here.

This is so interesting and informative. Thank you so much.

Thanks for the introduction to Sōseki.