🍂 Footnotes #5 | Antidote to Consumerism

In this edition: Marguerite Yourcenar, Oliver Burkeman, Gustave Flaubert, Simone Weil, Ayn Rand and others

💭 Word of the week:

Amor fati - ‘love of one’s fate’. A philosophy of life in which you view every event as a necessary part of the journey that must be accepted and embraced.

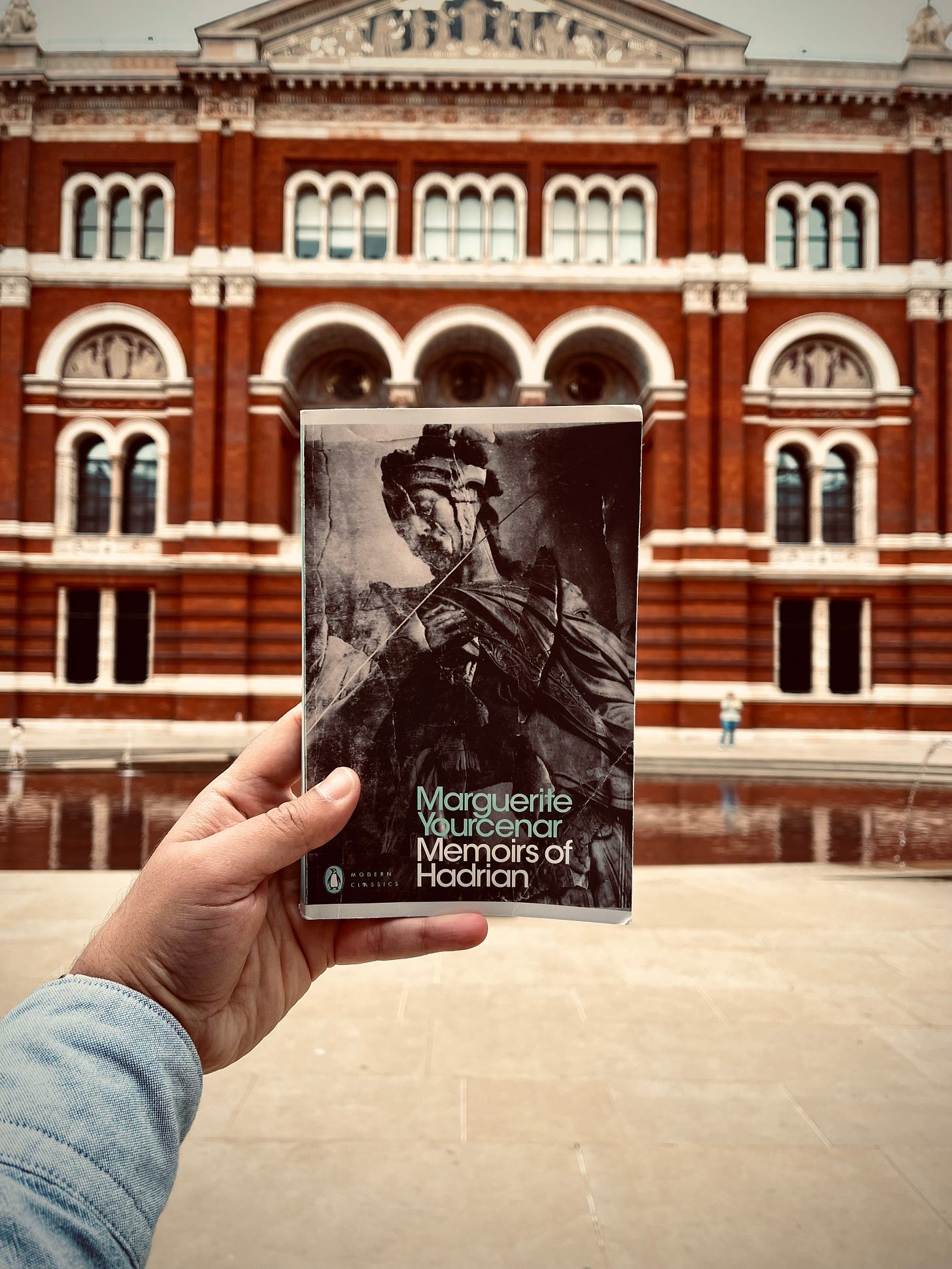

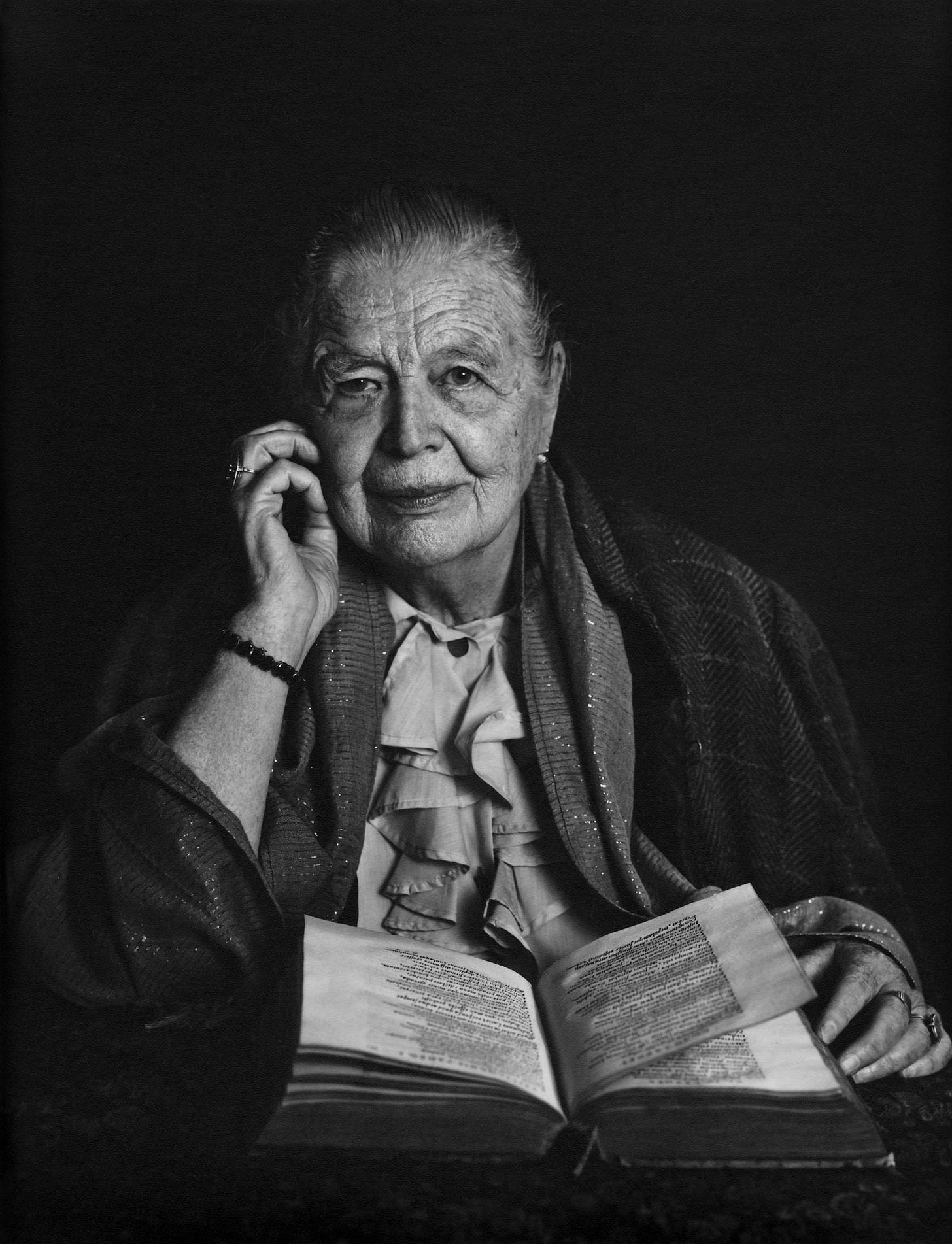

It’s often the greatest books that are the most challenging to review and Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian is one of them. Her writing is peerless, her genius limitless. This book is one of my most highlighted reads. There are a myriad of life-changing ideas in Yourcenar’s work, so I found myself annotating each page of it and recorded around two dozen different entries about it in my journal.

In this letter, I would like to share one of the journal entries I made while reading this remarkable book.

In his introduction to this book, Paul Bailey writes:

A humanist herself, a sceptic by nature, Marguerite Yourcenar presents us in these memoirs with one of mankind's best friends, an architect of peace and justice as well as buildings.

Written in the form of an extended letter to his successor, Marcus Aurelius, the book is Hadrian's valediction to a world that has pleased him. It opens with premonitions of his imminent decease and closes with his drifting quietly away from life, surrounded by adoring friends and servants.

It is, in fact, the preparation for death, the ultimate acceptance of it, that lends to these imagined memoirs their incomparable authority, particularly in a culture like ours, where the biggest taboo is our own mortality, not sex.

Bailey gives us a brilliant description of what the book is about, but it's the final sentence to which I wish to direct your attention, my dear reader.

‘in a culture like ours, where the biggest taboo is our own mortality, not sex.’

The relationship between sex and mortality has undergone a reversal over the past century. Once considered a taboo subject, sex is now openly discussed, while mortality, previously not a taboo, has become one in our modern culture.

For centuries, our ancestors were well aware of our mortality and the inherent limits of life. Artists, writers, and thinkers openly engaged in discussions about these topics. A compelling illustration of this is the painting below by Herman Steenwyck, titled 'An Allegory of the Vanities of Life.' A copy of painting like this would be on a wall of almost every household in Europe just a century ago.

However, the ascent of consumerist culture rendered conversations about mortality taboo. You might wonder, 'How?' and 'Why?’

Consumerism, as a lifestyle, dismisses the concept of limits. Its core tenet is to persuade you that the essence of life lies in ceaseless consumption of unnecessary items.

Take music streaming platforms, for instance; they offer access to approximately 45 million songs. A quick calculation reveals that it would require around 256 years, equivalent to three average lifespans, to listen to each one of them if the average track length is 3 minutes.

Some might argue that my logic is flawed because music platforms don’t say we should listen to all 45 mil. of songs, they simply grant us a choice. In response, I'd like to reference a finding by Nielsen, which discovered that users of movie-streaming platforms like Netflix are often overwhelmed by the overwhelming array of choices, leading them to opt out of the service without watching anything.

The cult of productivity is yet another manifestation of our culture's denial of mortality. In his insightful book '4000 Weeks: Time Management for Mortals,' Oliver Burkeman expounds on the contemporary promise and philosophy of productivity, which suggests that mastering our calendars will enable us to achieve everything we've ever dreamed of.

‘After all, it’s painful to confront how limited your time is, because it means that tough choices are inevitable and that you won’t have time for all you once dreamed you might do.’

~ Burkeman, 4000 Weeks

Mortality, in contrast, forces us to recognise that things are limited. It means that you won’t be able to read all the books you want; it means you’ll get to visit some places just once in the lifetime; it means that you won’t have time to be friends with everyone, just the select few.

Mortality teaches us how to reflect upon what is truly meaningful to us. Mortality tells us that each time we choose what or whom to pay attention to, we also choose how we define your lives.

If consumerism is poison, mortality, paradoxically is a cure. Or better to say its antidote.

The reason why mortality is a taboo conversation today is not because it’s a morbid or dark topic to talk about, but because mortality is consumerism’s mortal enemy.

Confide tibimet.

🍂 Footnotes

A couple of books coming soon that I’m excited about: Flaubert’s Selected Letters published by New York Review of Books coming September 26th, and Simone Weil’s ‘Need for Roots’ coming a month later on October 26th by Penguin books

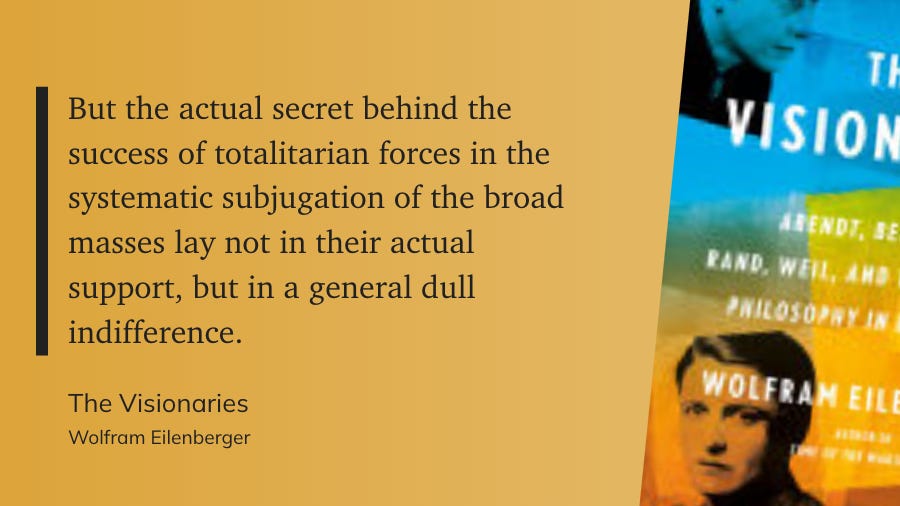

From Eilenberger’s book. Totalitarian governments succeed when ordinary people remain indifferent. (Quote by Ayn Rand, whose ideas seem to me simple, but in this case she’s correct)

This story of unsung heroes who worked on the Oxford English Dictionary is wonderful

Laughed really hard when discovered this failed restoration attempt of a painting called Ecce Homo. 👇 (Such an epic fail)

This study by a neuroscientist Katja Wiech from Oxford Uni back in 2008 showed that people with religious belief feel less physical pain.

I found paintings by the Victorian artist Richard Dadd interesting but also haunting.

I am currently…

📖 Currently reading: The Visionaries by Wolfram Eilenberger (finished W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz - he is genius. )

🎧 Current audiobook: Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War

📚 Book(s) Bought this Week: Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics

Book Review Coming Next Week:

🖋️ Quote of the week

I should take little comfort in a world without books, but reality is not to be found in them because it is not there whole.

Direct observation of man is a method still less satisfactory, limited as it frequently is to the cheap reflections which human malice enjoys.

Rank, position, all such hazards tend to restrict the field of vision for the student of mankind: my slave has totally different facilities for observing me from what I possess for observing him Iis s to do so are as limited as my own.