Géricault: What Happens When You Lose Hope

Deconstructing ‘The Raft of Medusa’: A true tale of hope and despair.

Hello friends,

This article explores one of the most haunting paintings I have ever seen, and perhaps the most significant piece I have ever written.

The story behind Géricault’s ‘The Raft of Medusa’ left me sleepless for many nights ever since I wrote about it. I write to preserve the greatest stories I encounter— in books, films, paintings, or sculptures. I revisit my pieces to refine my writing skills and to remind myself of the stories that captivated me at the time. Yet, since I wrote about The Raft four years ago, I have avoided revisiting it. The images of this horrifying story are too vivid, but as you will see, they still have a lesson to teach to those whose hearts are open to empathy.

Vashik Armenikus 🍂

‘Géricault allowed me to see his Raft of Medusa while he was still working on it. It made so tremendous an impression on me that when I came out of the studio I started running like a madman and did not stop till I reached my own room.’

~ Eugène Delacroix, Diaries 1817

Delacroix was not the only one who was driven close to madness by Gericault’s painting. Since its creation ‘The Raft of Medusa’ instilled a fanatical and even religious devotion among its admirers. This is not surprising since it is impossible not to go mad when you face the unimaginable horror that it depicts.

Towards the Catastrophe

In June 1816, a French frigate named Medusa with two other ships in its convoy departed from the French port of Rochefort. Medusa carried 400 people on board and was bound for the port of Saint-Louis in Senegal.

The captain was Viscount de Chaumereys, an aristocrat appointed to the position by King Louis XVIII, but who had not sailed in the last 20 years.

In an attempt to make good time, de Chaumereys decided to overtake two other ships, Echo and Argus, but due to his inexperience and poor navigation, the ship drifted 100 miles off its course.

A day later, on the second of July, de Chaumereys ran Medusa aground off the coast of West Africa. Due to the lack of lifeboats on board it was not possible to evacuate all 400 passengers at once, the plan was to make two trips to the shore and back. The supplies that remained on board were planned to be towed with the use of a small makeshift raft.

Alexandre Corréard, a young engineer from Paris, started constructing the raft. It had to be strong enough to carry many barrels of wine, food, passengers’ belongings, and no more than 10 people who would help steer while it was being towed.

Not long after the construction of the raft, Corréard noticed that Medusa’s bow was slowly beginning to collapse and leak. The fear among those who remained on board increased as the weather began to change and brought strong ocean waves which hit the doomed Medusa with increasing ferocity.

This created a panic amongst the passengers who were considered to be ‘low-ranking’ members of the ship, which included the soldiers, sailors and Corréard himself. The spaces on the lifeboats were already taken by their superiors. Moreover, since the captain ordered to load the makeshift raft with the supplies first, the space on it was getting scarce as well.

In fear of drowning, the remaining 147 passengers jumped on the small raft that was towed by the lifeboat. The raft went well beyond its capacity. Throwing some of the barrels and provisions overboard did free up space, it did not decrease the weight of it quite enough.

The panic among those on the raft increased and some tried to jump on the lifeboat towing it. At that moment the captain made the decision that later became a symbol and an allegory of injustice — he cut the rope between the two vessels sending the members of the raft adrift 13 days.

The bitter taste of despair

Insomnia drove the French painter Théodore Géricault mad after he read about the fate of those 147 people on board of the raft. Only fifteen survived and only two out of the fifteen were willing to tell what happened afterwards. One of the two was the young engineer Alexandre Corréard.

The year after the tragedy, Géricault met Corréard in the former’s home, and some say he was mystified by the fact that Corréard was eating whole lemons whilst he recounted the events.

Corréard’s story was not one of hope and heroism, but of madness and despair. This went against the accepted notion that the intellectuals of France had at the time. French political philosophers portrayed the human nature as essentially good. They claimed that all existing evil was born from the corrupt institutions that spoil human nature. ‘Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains’ said the French political philosopher Rousseau.

But the story that Corréard told Géricault proved Rousseau’s theories absolutely wrong.

For the next 13 days, each passenger of the doomed raft fought for his own survival against everyone else. This was not the world of ‘good natured’ people that was described by Rousseau, but it was the world described by another more pragmatic philosopher — Thomas Hobbes — who wrote that ‘the condition of man… is a condition of war of everyone against everyone.’

It took only three days, since the ‘Medusa’ ran aground, for the first cases of cannibalism to occur on the raft. At first, they did not kill to eat, only those who drowned were eaten. But it was not long after when the strong and healthy began to kill those who were weak and ill.

When small mutinies threatened to leave no one alive on board, the passengers of the raft agreed to throw their weapons into the sea. But, that did not help to avoid more deaths from violence.

On the eleventh day, fate mocked them cruelly. A butterfly flew next to the raft and then landed on a barrel. Those doomed passengers saw this as if God was communicating with them through nature. The butterfly reminded them of the Biblical story of Noah who received an olive branch in the beak of a dove after surviving the Great Flood.

Two days later, the raft was spotted by an English ship ‘Argus’, only 15 out of 147 people initially on board remained alive at that time. The English captain and his crew were so horrified by what they witnessed that some historians write the captain went insane months later.

Géricault soon understood why Corréard was eating lemons in such large quantities. The acid taste of the fruit helped the young engineer to rid of the foul taste of human flesh he devoured whilst on board that damned raft.

The Anatomy of the Painting

Well, so which moment of this catastrophe did Géricault choose to draw?

He could have drawn the moment when the Medusa struck the reef; or the moment the captain cut the towropes; or the murderous mutinies at night; or the moment when the butterfly landed on the raft.

But he didn’t. Instead, he chose the moment when the passengers of the raft saw the ship in a far distance. We might think that this is the moment when the English ship ‘Argus’ rescued the doomed sailors of the raft.

In truth, Argus did not initially notice the raft when it passed it for the first time. It appeared on the horizon for half an hour (far but close enough for the members of the raft to see) and then disappeared. Géricault focused his work on this moment of sudden intense hope and the equally sudden and intense despair.

‘Some believe it is still coming towards them;’ — writes Julian Barnes in his book Keeping an Eye Open — ‘some are uncertain and waiting to see what happens; some know that it is heading away from them, and that they will not be saved. This figure incites us to read ‘The Shipwreck’ as an image of hope being mocked.’

But the painting — or any artwork — that survives is the one that outlives its story. If Géricault wanted momentary fame at the risk of creating a political scandal, he could have drawn the moment of cutting the towrope, or the scenes of cannibalism.

He tried to explore the moment of human degradation. In the pursuit of realism, he visited his local morgue to observe the decaying dead bodies. There were rumours that he kept severed limbs and heads ‘borrowed’ from the morgue in his art studio.

He was a dandy and enjoyed attending meetings, parties, and social events. He decided to shave his head when he began to work on ‘Medusa’, to be too ashamed to attend those social gatherings and dedicate his attention solely to his work. He constructed the life-size raft in his study from instructions which he borrowed from Corréard, who constructed the original one.

It is hard not to draw parallels between Géricault’s approach to painting to that of Leonardo Da Vinci. Leonardo was also a frequent visitor to hospitals in Florence, where he observed changes in the human body during their decay.

When this masterpiece was first exhibited in the Paris Salon it went under a different name — Scène de Naufrage (french ‘Shipwreck Scene). The name ‘Medusa’ was not mentioned, but everyone who came to see this painting instantly understood which event Géricault referred to. Only three years had passed since the catastrophe and the images of its horrors were still fresh in the public’s mind. He chose this neutral title for his masterpiece because he wasn’t looking for an ephemeral political scandal, he wanted to achieve immortality as an artist.

When Louis XVIII saw the painting he told Géricault:

‘Monsieur, Medusa was a disaster, but your painting is everything but that’.

Géricault saw an eternal theme that accompanies all of us throughout our lives — that of hope. To be able to fully express this, he introduced biblical elements that were used during the Renaissance into the Neoclassical style popular at his time.

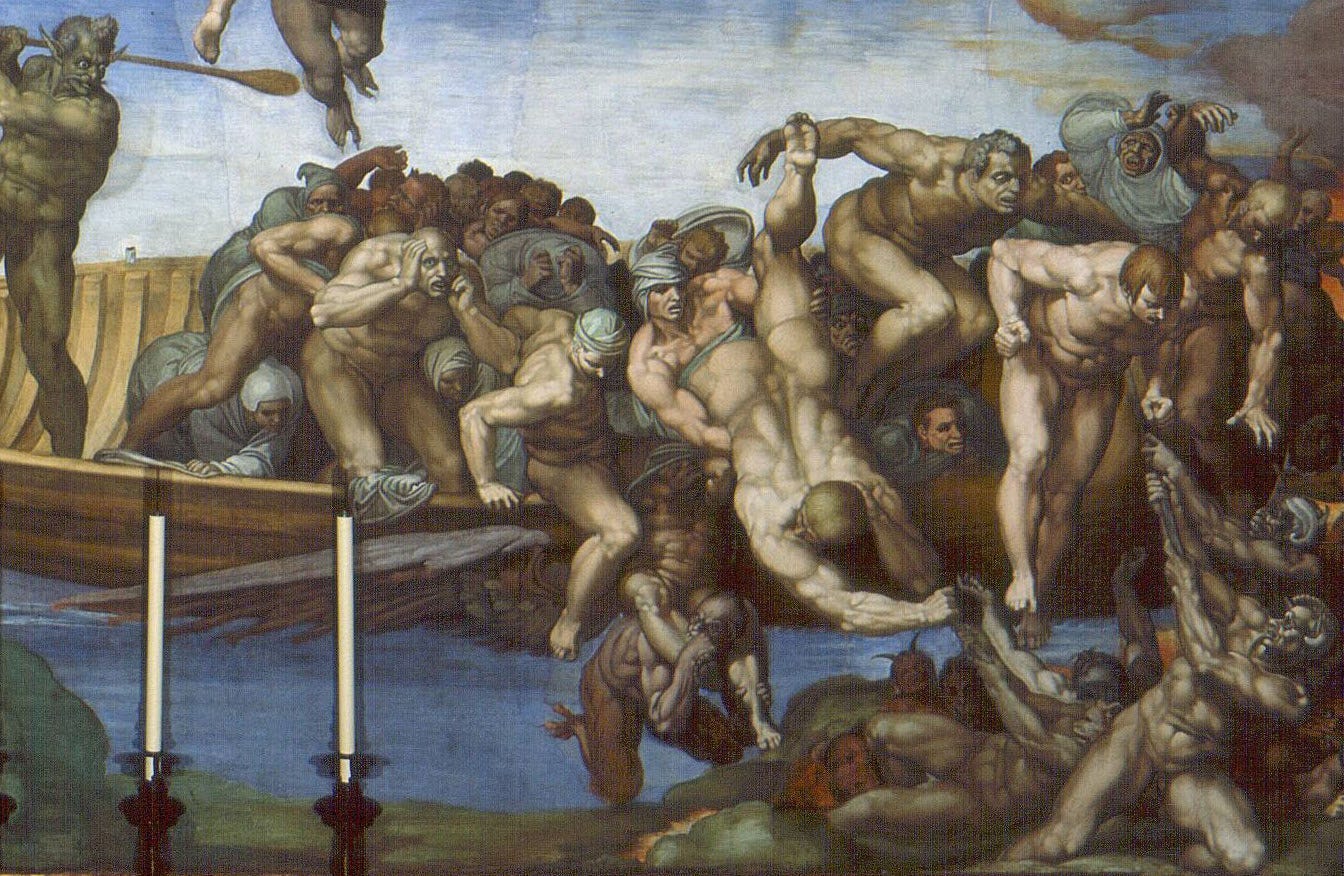

We can also witness how he borrowed from the style of Michelangelo. Particularly from the fresco The Last Judgement which Michelangelo painted on the ceiling of Sistine Chapel. The scene resembles the one in Géricault’s masterpiece.

The naval painting was one of the subjects often depicted by the French masters at the time. Géricault was inspired particularly by a painting called ‘The Shipwreck’ drawn by a fellow Frenchman — the naval painter Claude Joseph Vernet.

Géricault borrowed and then improved on the techniques of his predecessors. In this work, he employed a technique called ‘foreshortening’, in which the painting appears to spill over the borders of its frame, which we can see at its bottom right. The ‘foreshortening’ draws the viewer straight into action. It is as if the people on board the raft try to escape from the painting itself. We can see this in the naked dead passenger, who is coming out of the frame of the painting on the right.

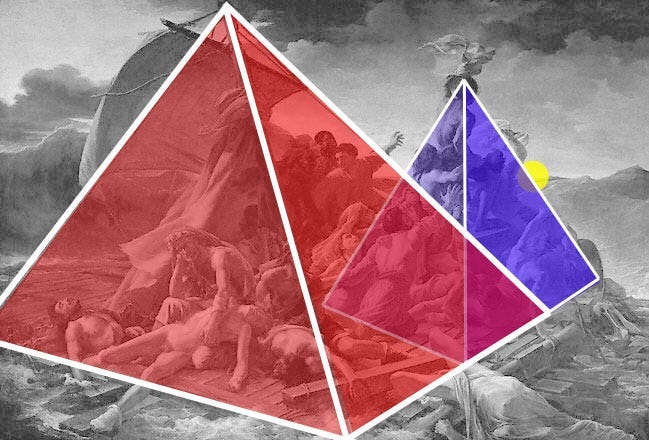

Géricault constructs his story by employing two pyramidal elements; the mast which makes part of the top of the pyramid, divides the passengers into two groups: those in despair on the left and those who persistently hold onto the hope on the right.

On the left, we can see an old man mourning with a young dead sailor lying on his lap. The old man is Ugolino — a character from Dante’s Divine Comedy. He was guilty of cannibalism and was placed in one of the most horrific circles of hell by Dante.

The mast itself symbolises the Christian cross. Those who we find on its left are people who got involved in sin (such as cannibalism); while those on the right side of it are those who did not lose their faith and hope to be rescued.

We can see a man on the barrel who signals to the British vessel which would soon disappear, as if to mock their hopes, but then return. Behind the man, we see their reactions to this hope.

We see a red-haired man stretching his hand towards the horizon, in an attempt to see the English ship, while completely ignoring the fact that someone has just bitten into his flesh.

This is the final fight between life and death, hope and despair, sin and faith. This is when the weak try to drag the strong and when the strong refuse to support the weak.

We see a black-haired man trying to shrug off the hands of the dead who try to pull him towards the left — the doomed side — of the raft. We have heard of this man before, this is the man who said he had to ‘run like a madman’ when he saw Géricault’s painting. This is a French painter who will a decade later revolutionise art himself — this is Eugéne Delacroix.

How can one not become mad, at least temporarily, after looking carefully at this painting?

From all the scenes that Géricault could choose, he undoubtedly chose the most meaningful, the most horrid, and the most intense moment in this catastrophe. The amount of detail and research that he conducted makes his masterpiece one of the most realistic works in the history of art. This is no exaggeration.

Géricault did not leave any side of his work untouched or wasted. It can be read as a sentence in a book, from left to right. If the right side of the raft is accompanied by the ship that inspires hope; the left side of the raft comes with a giant, powerful wave which is about to shatter the raft’s last remaining integrity and plunge everyone into the abyss.

‘We are all on the raft of Medusa’

The most prominent of Géricault’s biographers Denise Aime-Azam wrote that Géricault hated his masterpiece. ‘He wanted to cut it and to destroy it’ — she said in 1993. He went mad after finishing it. But once on his deathbed, at the age of 32, he asked his pupils to draw a small copy of his masterpiece and hang it in front of him.

Aime-Azam knew, as no one else, how difficult it is to write the biography of Géricault. The truth is that although he had a very rich life he did not leave many records of his own thoughts. The only way for us to understand Géricault is through his paintings and everyone interprets them in their own way.

There are twenty people depicted on board the Géricault’s raft. They all, of course, differ: black or white, dead or alive, hopeful or in despair. But I believe these are not different, separate individuals, but they only represent various stages and courses in the journey that we call life.

‘We are all on the raft of Medusa’ said historian Jules Michelet, a contemporary of Géricault, when he saw the painting on display in Paris.

This is why this painting instills a certain dose of madness in its admirers. I believe that is why Géricault, at the end of his life, came to terms with it and hung it in front of him. Because his masterpiece, in the words of the poet Arthur Rimbaud, represents that: ‘Life is the farce we are all forced to endure.’

I may not have had the time right now to sit and read through this whole article, but the voiceover was really easy to listen to and extremely convenient. Thank you for sharing and taking the time to read aloud.

Very evocative, thank you! 🙏