How to Read Like Leonardo Da Vinci?

A reader should be careful with his reading diet and try not to contaminate himself.

A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a re-reader.

— Vladimir Nabokov

In1499, Leonardo da Vinci moved from Milan — the city where he had spent last seven years of his life — and returned to his native Florence. Among his belongings were several items of clothes, multiple types of drawing and art supplies, and one-hundred books. He came from a wealthy family but he had never received what was considered ‘official education’, because he was born out of wedlock.

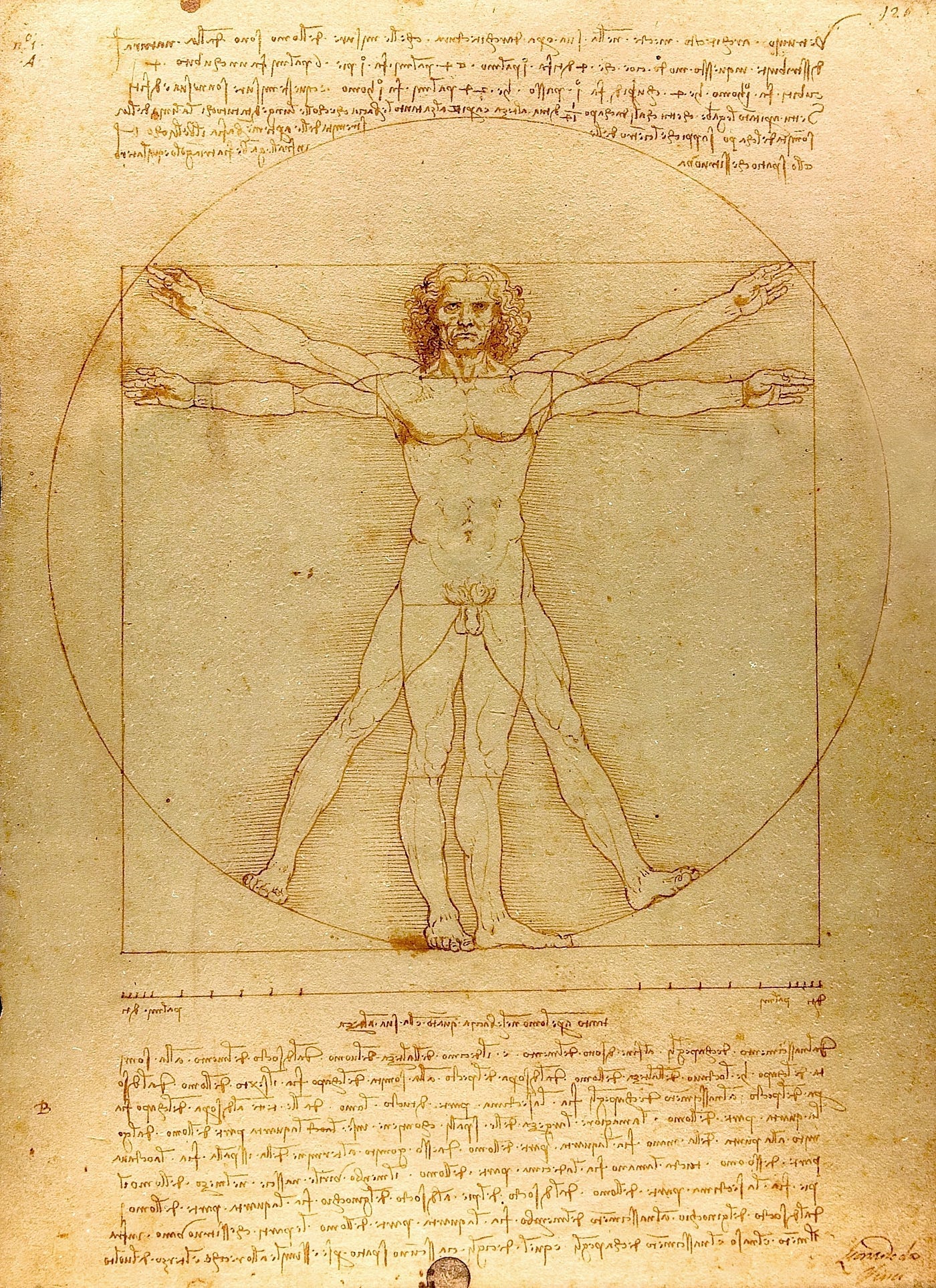

Everything he knew, he owed to nature and books. In his recent biography of Leonardo, Walter Isaacson tells how the young genius used to spend hours observing birds fly and then sketching in his notebook the structure of their wings. What Leonardo couldn’t find in nature, he found in books. He could spend weeks, if not months, studying works of other geniuses. He drew his famous Vitruvian Man by studying works of Vitruvius — architect and civil engineer of ancient Rome.

This was before the invention of the Gutenberg’s printing press. Books were scarce and hard to find at the time. Many famous stories and scientific theories were simply passed by word-of-mouth. If a book existed, it existed because it was considered essential for civilisation. If it was a work of literature, it had to be deep and profound enough for the audience to discover a new meaning every time they read it (as in Dante’s Divine Comedy); if it was a scientific work, to be published, it had to surpass previous discoveries, as Galileo’s surpassed that of Copernicus.

These circumstances created a certain type of reader. A reader who was as engaged as Leonardo, as profound as Galileo, and as appreciative as Michelangelo. Isaacson’s biography tells a story of how Michelangelo used to walk on the streets of Florence reciting Cantos from Dante’s Divine Comedy which he knew by heart.

By the time he passed away at the age of 67, Leonardo left over 6000 pages of notebooks full of anatomical studies, military inventions and sketches of nature. But his notebooks also included notes that he made from the books that he got access to in libraries.

I was lucky to be able to visit an exhibition organised by the Royal Collection Trust in London in June 2019. The exhibition was dedicated to the 500th anniversary of the of Leonardo Da Vinci.

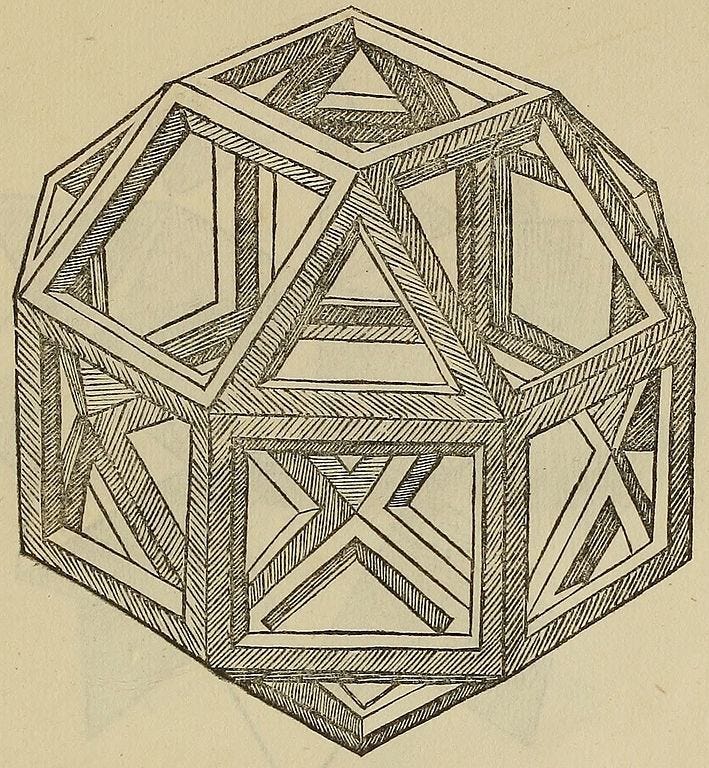

While standing in front of the pages of his notebooks, I was witnessing how Leonardo read the books he got access to. He learned maths with the help of Luca Pacioli’s encyclopedia. He copied Pacioli’s studies to his notebook and added his own thoughts and ideas to expand the mathematician’s theories.

The difference between the ‘Renaissance reader’ and the ‘modern reader’

Reading habits have changed significantly since the times of Leonardo. The main shift occurred with the advent of the printing press. It allowed to produce books faster and cheaper. If this technology was available a millennia or two before, we could preserve the Library of Alexandria. But there’s a dark side of everything, with the books getting cheaper and more accessible, the quality of reading had fallen as well.

For example, my personal library exceeds 3000 volumes of books that touch upon various subjects, while Leonardo’s library consisted of only 100 books when he left Milan. By no means I want to compare myself to Leonardo, but I would like to show that contrast in reading habits between me as ‘a modern-reader’ and Leonardo as a ‘Renaissance reader’.

The rise of printing press created a lot of ‘noise’ in the world of books. Today we’ve reached a point, when hundreds of thousands of new titles are being published each year in the United States alone. A modern reader is faced with a problem that Leonardo couldn’t even imagine at his time — the problem of choice.

This problem — of having too much choice — was recognised by the one of the most prominent Italian authors of 20th century — Italo Calvino. He tried to address this discrepancy in his long-essay called ‘Why Read Classics?’. For Calvino reading can be dangerous if not treated seriously:

‘ a reader should be careful with his reading diet and try not to contaminate himself. Of course it’s difficult for the modern man to read classical works of Proust, Montaigne, Valéry only… But feeding yourself exclusively with the recent sociological survey or the latest bestseller can be equally devastating for the mind.’

(~ translated by the author of this article from French.)

Calvino says that reading classics helps the reader to look at the timeless faculties of our life; to witness that the problems of today have existed long time in the past. However, Calvino also recognises that the modern reader cannot cut themselves completely out from the events that happen at their age. He says that modern reader should learn how to balance between the timeless works of art & current events.

‘Perhaps the ideal reader would be able to perceive the news as the buzz of the streets — which warns us, through the window, of car traffic and weather changes — while following the discourse of the classics, which resonates, clear and structured in the room. But that’s a lot to ask from the majority of people whose rooms are filled with traffic noises and their television is set to full-volume every minute.’

(~ translated by the author of this article from French.)

But what can be ‘a classic’ and what is not?

As the book-market grew, we started to attach the word ‘classic’ to be able to distinguish a tasteless work of art from an exceptional one. The word ‘classic’ or ‘classical’ was almost out of use in 1800s, according to the Oxford dictionary, but started to grow from the start of 20th century . We needed a word that could instantly say to a customer standing in a bookshop: ‘This book is exceptional from all the others’.

Umberto Eco — the author of ‘The Name of the Rose’, a book that many critics call ‘a modern classic’. In his lecture at the University of Bologna, he suggested his brilliant definition of what makes a classic:

‘What is a classic? It’s a survivor. Aristotle cites number of plays in his Poetics, but we don’t know about most of them. Why? Because they’ve not survived. Why did one book survive and not the other? We don’t know, but we have to have a faith in historical filtering’.

(~ translated from Italian by the author of this article, original here)

I also believe that history acts as a filter. Even today, we don’t know quite how much we, as a civilisation, lost during the fire in the Library of Alexandria — the largest library of the ancient world which burned down in 48 B.C. taking away thousands of books.

Leonardo, as a ‘renaissance reader’, didn’t face the problem of ‘the noise’ that we do face today. The works of Vitruvius, Pacioli or Dante weren’t classics for him, because ‘mass-market’ wasn’t invented at his time yet. Leonardo chose what to read from a limited amount of exceptional works that were selected, copied and preserved for him by centuries.

Merging the ‘Renaissance Reader’ with the ‘Modern’.

The word ‘classic’ therefore will help us to identify what to read or, in other words, what Leonardo would have read if he was born today. We need to merge the modern-reader (who has learnt how to identify what book is a classic) with the reader like Leonardo (who read meticulously each book to hand).

To achieve this, we — the modern readers — need to reject the side-effect that came with the rise of mass-publishing — the technique of speed-reading. There is a lot of advice today on how to read more books and to read them more quickly, yet little advice on how to read them well and more thoroughly. To tell someone that you have only read one great book last year and have learnt it by heart sounds less attractive than to tell someone that you read 100+ books last year. Quantity is everything today.

But once we pick up a classic such Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy’ or Nietzsche’s ‘Thus Spoke Zarathustra’, we realise that speed-reading can be advocated only by those who have never read a masterpiece of a written word. Each sentence in these works is dense with life-changing and mind-altering ideas that shift our perceptions forever.

Oscar Wilde, in his diaries, mentions that he spent an entire week trying to decide where exactly to put a comma in one of the sentences of his famous novel ‘The Portrait of Dorian Gray’. A true writer has to fall in love with each sentence which he or she decides to put on paper. It’s the task of the reader to appreciate it.

Bill Gates reads many books because it’s his habit. In multiple interviews and in his own blog, he tells how seriously he takes his favourite habit. He has a famous ‘book bag’ in which he carries volumes that he plans to read. He books time off to sit and focus on his reading. And to remember what he has read he makes notes on the margins.

People who read impressive number of books are usually those for whom reading is a habit. Bill Gates reads many books because it’s his habit. He imitates the habit of his hero Leonardo Da Vinci.

Bill Gates is the closest public figure who resembles the amalgam of the ‘renaissance’ and ‘modern-reader’ merged together. It is likely that Bill Gates imitates the habit of his hero, Leonardo Da Vinci. After all, Gates spent millions to own some pages from Leonardo’s famous notebooks. From Walter Isaacson’s biography, we know that Leonardo also took notes from the books he read. He obviously left notes in his notebooks and not the margins of the books. But the level of engagement was the same. Perhaps, Leonardo would have owned more books if he lived at our time, but I doubt he would respect speed-reading.

This article was originally published in October, 2020 on Medium.

I no longer write there, so thought I would share some of the pieces here.

Fascinating study comparing the modern and renaissance reader. Considering the importance of reading classics, do you ever return to “lighter” works so as to clean your palette before reading heavier works?

Whilst I agree with you on the importance of the classics I wonder if there should still be a space for books which are less rich in literary prowess yet still exhilarating from a plot perspective.

What an important piece of writing. I appreciate you sharing this here and giving me as well as so many others the chance to read it.

Over the past couple of years I have tried more conscientiously to read a combination of classics and contemporaries. It has surely done wonders, and I do recommend reading well more than I do reading many!