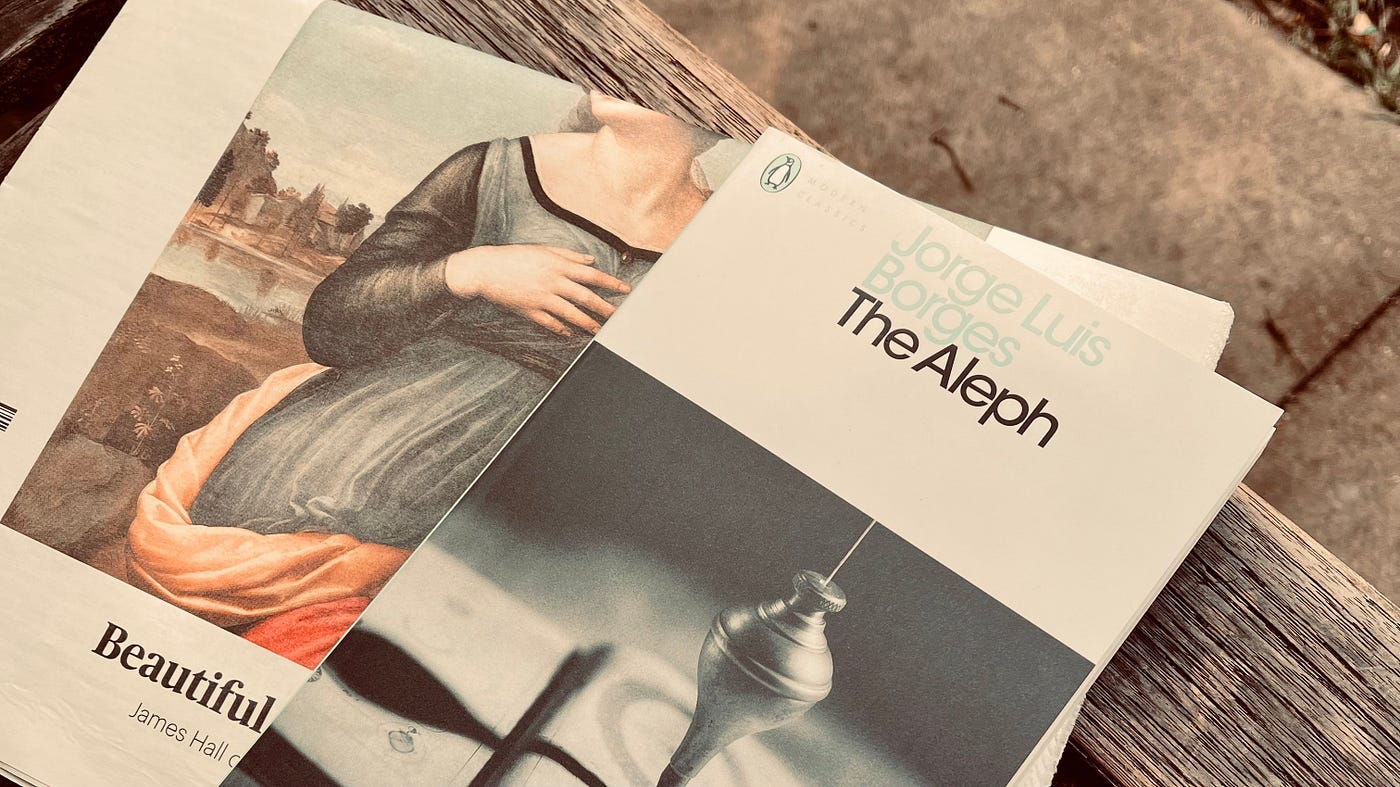

“Writing is nothing more than a guided dream.”

― Jorge Luis Borges

Great literature often precedes contemporary science. The imagination of great writers senses truths that scientists are yet to discover.

The Argentinian writer Jorge Louis Borges was gifted precisely with this kind of oracular imagination.

In 1942, one of the leading Argentinian newspapers La Nación published a short fantasy story by Borges in which he inadvertently described yet unexplored inner workings of our brain.

The title of that story was ‘Funes the Memorious’.

It is a tale of a man called Ireneo Funes. The narrator (a fictional version of Borges) encounters Funes on his way to the Uruguayan village of Fray Bentos in 1884. The fictional Borges asks this man what time it is and Funes replies by telling the precise time, minute by minute, without even looking at his watch.

After a brief stay in Fray Bentos, the fictional Borges leaves it and then returns three years later in 1887. He comes back to spend some peaceful time in this remote village and brings with him books written in Latin, including Pliny’s Historia Naturalis.

Soon he receives a note from the mother of Ireneo Funes. The note says that Funes suffered a tragic accident a year ago. He fell from a horse and is now hopelessly crippled. The mother asks Borges if he could lend some of his books to her son. Borges agrees and sends his copy of Pliny’s work without any hope that the young man will be capable to read it since Funes doesn’t speak any Latin and Pliny’s work spans several thousand pages.

Days later, Borges receives a telegram from Buenos Aires asking him to come back because of his father’s ill health. As he packs his suitcases he realises that he left Pliny’s work with Funes.

Borges visits him and as he enters the house he is greeted by Funes reciting Pliny in perfect Latin. The scene unfolds and Borges realises that Funes managed to memorise the entirety of Pliny’s book by heart just in few days.

It turned out that the tragic accident took away from Funes his capacity to move, but left him with an extraordinary ability to remember everything he ever encounters.

“Funes remembered not only every leaf of every tree of every wood, but also every one of the times he had perceived or imagined it.” ~ Borges, Funes the Memorious

Ireneo Funes could remember every tiny detail of everything he ever encountered in his life. He was incapable of forgetting.

This prodigious quality came at a price. Funes could recite Pliny by heart but couldn’t understand the meaning of what he was reciting. He lost his capacity for general thinking.

“He was almost incapable of ideas of a general, Platonic sort. Not only was it difficult for him to comprehend that the generic symbol dog embraces so many unlike individuals of diverse size and form; it bothered him that the dog at three fourteen (seen from the side) should have the same name as the dog at three fifteen (seen from the front).” ~ Borges, Funes the Memorious

Funes also couldn’t sleep, because, as Borges writes ‘to sleep is to turn one’s mind from the world;’

Funes’ mind was too engaged with memorising all the tiny details of this world to be capable to switch off his mind.

The Science behind Ireneo Funes.

Precisely 79 years after the publication of Borges’ story, Ian McGilchrist, a psychiatrist and literary scholar at Oxford University, published a book called The Matter with Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World.

This book is enormous both in terms of quantity of pages (it’s 2000 pages long) and also in terms of quality ( McGilchrist brings together 3 fields of study: neuropsychology, metaphysics, and epistemology.)

One of the many central ideas of this book revolves around the division of our brain between the Left-Hemisphere (LH) and the Right-Hemisphere (RH).

‘The LH is principally concerned with manipulation of the world; the RH with understanding the world as a whole and how to relate to it.’ ~ McGilchrist

McGilchrist writes that each part of our brain gives us a different interpretation of the world that we see around us.

The best way to understand the difference between the functions of the left and the right side of our brain is by looking at how it works in nature.

‘Every animal, in order to survive, has to solve a conundrum: how to eat without being eaten. It has to pay precisely focussed, narrow-beam attention that is already committed to whatever is of interest to it, so as to exploit the world for food and shelter. Put at its simplest, a bird must be able to distinguish a seed from the background of gravel on which it lies, and pick it up swiftly and accurately; similarly, with a twig to build a nest.’ ~ McGilchrist

The human brain also works this way and it also comes from the LH of our brain. This is not enough, however, for our survival. In order to survive we also need to be able to map and keep an eye on the world around us. The world that we haven’t yet explored.

‘Yet, if the bird is to survive, it must also, at one and the same time, pay another kind of attention to the world, which is the precise opposite of the first: broad, open, sustained, vigilant attention, on the lookout for predators or for conspecifics, for friend or foe, but also, crucially, open to the appearance of the utterly unfamiliar — whatever may exist in the world of which it had no previous knowledge.’ ~ McGilchrist

In other words, the LH of our brain deals with the practical, with the familiar, with the detail.

The RH of our brain in contrast deals with ‘the whole picture, including the periphery or background, and all that is not immediately graspable.’

I am certain that my reader now can understand what connection I try to draw here between McGilchirst’s ideas and Borges’ story about Ireneo Funes.

When Ireneo Funes fell from the horse he lost the capacities that belong to the RH of our brain.

McGilchrist writes:

“The LH tends to see things as explicit and decontextualised, whereas the RH tends to see them as implicit and embedded in a context. As a result, the LH largely fails to understand metaphor, myth, irony, tone of voice, jokes, humour more generally, and poetry, and tends to take things literally”

This is what Funes lost his capacity for. He couldn’t understand any generalities, he couldn’t sleep, he couldn’t dream, he took everything literally.

His own face in the mirror, his own hands, surprised him every time he saw them. ~ Borges, Funes the Memorious.

He couldn’t even recognise himself in a mirror, because each day he got older and each day tiny wrinkles appeared on his face, making him look different, like a different person.

The Matter with Things is 2000 pages long and 300 of those pages consist of bibliography. McGilchrist cites many respectable neuroscientists who studied the dichotomy between the LH and RH of our brain and how it shapes our consciousness.

One of the key scientists in split-brain research was Roger Sperry, who won a Nobel Prize for his contributions to the field in 1982.

However, most of the scientific discoveries in the field were made over the past two decades, whilst Borges’ prophetical imagination described the same ideas five decades before.

What also left me speechless was when I read this:

The principal band of fibres that connects the two hemispheres at their base in humans, known as the corpus callosum, has got proportionately smaller, not larger, over evolution — and is, in any case, to a large extent inhibitory in function. ~ McGilchrist, The Matter with Things

The corpus callosum is the part of our brain that regulates the relationship between LH and RH of our brain. I am not a neuroscientist. I am just a curious person who asks questions and my question is this:

Is it possible that when Funes fell from his horse, he damaged his corpus callosum, which in its turn inhibited his access to the RH of his brain?

Whether Borges knew about those scientific details of how our brain operates is not important. The important thing is that the right hemisphere of Borges’ brain worked better than the left part.

It is the right hemisphere of his brain that allowed him to see the bigger picture, explore yet uncharted ideas, and write stories that trigger an endless chain of ideas in minds of his readers.

That’s the genius of Jorge Louis Borges.

This article was originally published in September, 2022 on Medium.

I no longer write there, so thought I would share some of the pieces here.

Notwithstanding its length, is the McGilchrist book accessible for general readers?

Beautifully reasoned. I have McGilchrist's tomes & am just starting volume two. His thinking is cross checked against a vast number of scientific & other papers. It makes for fascinating reading.