Undressing The Allegory Behind Lady Liberté

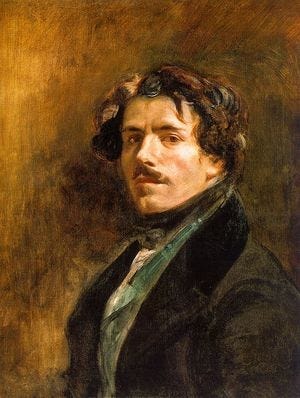

Reading the concealed references in Delacroix’s painting.

‘God, she is filthy’ wrote a French newspaper L’Avenir in 1831. ‘The lowest type of Harlot’ wrote a critic about Delacroix’s depiction of Lady Liberty in the Journal des Artistes in May of the same year. Overnight this painting became the most criticised artwork that was displayed in the famous Paris Salon.

The critics and art community were furious. In their eyes Delacroix dared to desecrate, humiliate and stain, not only the symbol of freedom and liberty, but also the sacred symbol of France. The image of the Lady Liberty was also based on the image of a goddess Marianne, an ancient mythological goddess, who became a personification of post-revolutionary France.

She is holding a rifle in her left hand and the French flag in the other. She is storming the barricades of royalist troops. If Delacroix painted Napoleon instead of her — this painting might have still made sense. In this painting she looks more like a military commander, a general, rather than a divine and pure goddess.

Delacroix was a revolutionary, he was a rebel, but only in his art and thoughts and not in political actions. Julian Barnes, in his book ‘Keep an Eye Open’ touches on the painting of Lady Liberty and sums up perfectly Delacroix’s thoughts on masses and 1830's revolution:

‘His instincts were purely reactionary. He judged man an ignoble and horrible animal whose natural condition was mediocrity. He thought truth existed only among superior individuals, not among the masses.’

In Lady Liberty Leading People I see Delacroix acting not as a supporter of masses, but as a prophet who tries to warn his viewers about the horror and misery that revolution brings with itself. He had seen the previous revolt and knows that this won’t be the last. I think it is for this reason that he chose to depict Marianne in this provocative way.

People often mistakenly think that this painting refers to 1789 French Revolution, but Delacroix depicts here the events that happened forty years after, in July 1830.

Just imagine if you were born in Paris around that time, in just forty years of your life you would witness the world change at least three or four times before you were forty years old. You would witness the fall of centuries old monarchy, then the rise and fall of Napoleonic Empire, then the fall of Charles X and then the fall of Louis-Philippe. France was in unprecedented political storm and this is exactly when Eugène Delacroix was born in 1798.

He heard and felt how the initial spark of freedom, at the end of eighteenth century, brought decades of political tyranny, horrid executions, unending wars and propaganda. However there was, perhaps, a secret that Eugene Delacroix possessed that helped him to survive in this tumult. Almost everyone knew this secret, but nobody dared to say it out loud. The secret was that he was the illegitimate son of one of the greatest diplomats in history — Charles Maurice de Talleyrand.

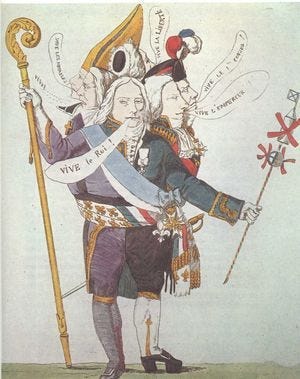

Talleyrand was a diplomat and advisor at the French court. He survived all kings, and an Emperor, who rose to power during his career. His character is exquisitely portrayed in a caricature called ‘The man with six heads’; each head praises each regime Talleyrand used to serve under, thus he shouts ‘Glory to the King!’, ‘Glory to Emperor!’ or ‘Glory to Council’. Napoleon and the Kings mistrusted Talleyrand but he knew ‘too much’ and his intelligence was too irreplaceable to get rid of. The name ‘Talleyrand’, even during his lifetime, became a synonym of a person who is thought to be crafty, cynical and calculative in his actions.

If Talleyrand expressed his thoughts subtly through speeches and letters; Delacroix tried to convey his thoughts subtly through painting. By painting Lady Liberty bare-chested Delacroix refers to an ancient Greek statue of Venus of Milo.

The Venus of Milo, which is also on display in Louvre, is a symbol of the Greek idea of democracy. Delacroix draws another parallel by dressing Lady Liberty in ripped, dirty and creased clothes. His intention was not, obviously, to desecrate the sacred symbol of Lady Liberty as his critics tried to blame him for. By this Delacroix tried to convey what that idea of liberty and democracy had become at his day.

The next we can see a woman kneeling under the feet of Lady Liberty. This woman, in a blue shirt is a farmer; she stares at the goddess full of hope that freedom and liberty will relieve her from the pain of war. There is a subtle symbolism here. She wears a red cloth on her head that looks like a phrygian cap, also a symbol of freedom, same as the one we see on the head of Lady Liberty.

The farmer is the only character who doesn’t hold a weapon and who doesn’t stare or march towards us. All others are about to attack us — as if we the viewers — are the royalist troops. At the bottom left corner, we can see a young man who swings his sword while hiding behind the rocks. He is a student at the local collège. Delacroix puts the symbol of his institution on the boy’s hat. It was precisely this boy and his fellow students who launched the revolution in 1830. They attacked the troops of Charles X, who came to destroy publishing house in Paris. Those students, who had a thirst for free-expression resisted the troops and later were joined in their fight by other Parisians.

That’s why the man in a top-hat and a rifle also joined the rebellious students. He is a journalist, a man of letters, whose thoughts were censored for decades. He is there right behind the Lady Liberty. This journalist doesn’t want to be like Talleyrand or Delacroix; he wants to express himself freely and clearly with no fear of prosecution. For the freedom to strive journalists must be able to express and reveal the problems openly and explicitly, not subtly or allegorically.

Behind him, wearing much dirtier clothes is a factory worker. Keep in mind that this was the time when industrialisation just began. This is when exploitation of working-class was on its way and was already felt by men like him and was later articulated by Karl Marx.

Factory worker has a red pin on his hat, this was used to identify those who were on the side of the revolution.

But there is another key symbol, a key event, that Delacroix leaves for the most observant of his works. Behind the boy who holds two pistols — and who later became a character of Victor Hugo’s ‘Les Miserables’ — we can witness how rebels stormed Notre Dame.

Notre Dame was the symbol of monarchy, of continuity, of conservatism and now it was in the hands of revolutionaries who hanged the tricolor above it. This is the only symbol by which Delacroix tells us almost explicitly that the rule of Charles X is over; the capital has surrendered to another revolution.

How easy it is to miss the dead bodies underneath the feet of revolution. When critics looked at this painting; they saw Lady Liberty, they saw the journalist and the factory worker; the student with the sword and the boy with pistols; they even saw Notre Dame with tricolor behind the vast white smoke. But they missed those dead in front of them. They missed Delacroix’s depiction of the consequences of revolution.

The man, who lies in the rubble on the left, is half naked with a single blue sock on his foot. He is, of course, the symbol of those who innocently die in the violence which they are not part of. Was he dragged out at night by the royal police, stripped naked and killed by them? Or maybe the revolutionaries had suspicions that he was a traitor, as it often used to happen, and killed him without finding any evidence? The subtlety of Delacroix’s brush is too deep to be interpreted precisely.

After all Delacroix said himself, in the diaries he used to write throughout his life, that painter shouldn’t and cannot convey his intentions as explicitly as a writer could possible do. The viewer has to seek their own interpretation.

The revolutionaries of this painting achieved their goal. They deposed the censorious king Charles X and he was replaced by another king — Louis-Philippe. It was him, actually, who bought the painting from Delacroix and put on display in Paris.

‘The viewers will witness symbol of freedom and the price that comes with it’ so he likely thought. But ten years later, he ordered this work to be removed from display and returned it to Delacroix. Some time later he was also overthrown and fled to the United Kingdom from where he never returned.

Art always outlives politics. The same way as Delacroix’s paintings outlived the achievements of his supposed father. Delacroix inspired a new generation of painters and changed the direction of the European art for decades to come such as Van Gogh, Latour, de Balleroy, Manet and more.

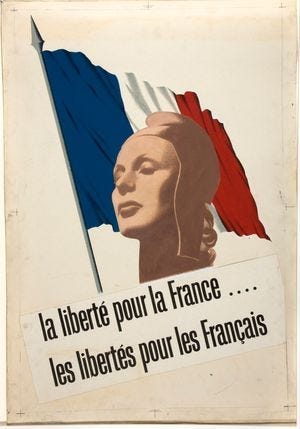

The image of Lady Liberty inspired French Résistance during the WW2. The posters with her could be seen across France throughout the war.

Nowadays, historians and art critics continue to dispute who served as a model for Lady Liberty and what meaning did Delacroix tried to convey in this allegory. The beauty of allegory, in my opinion, is in the fact that it’s an infinite well of different interpretations that each of us can draw from.

This article was originally published in September, 2020 on Medium.

I no longer write there, so thought I would share some of the pieces here.

The two figures of dead soldiers are interesting, too. They appear to be wearing different uniforms, but it’s hard to be sure of that.