Yousuf Karsh: Character, like a photograph, develops in darkness.

Photographer-Philosopher who took portraits of Churchill, Einstein, Hepburn, Elizabeth II and countless others

“Character, like a photograph, develops in darkness.”

~ Yousuf Karsh

I've also seen that great men are often lonely. This is understandable, because they have built such high standards for themselves that they often feel alone. But that same loneliness is part of their ability to create.

~ Yousuf Karsh

The symbol of Scotland is the unicorn; the symbol of Wales is the dragon—both mythical creatures. If I were to choose a mythical being to embody the Armenian spirit, it would undoubtedly be the phoenix. For no other creature rises anew in radiant glory after being reduced to ashes, no other being can reforge itself and breathe life once more after utter destruction more than the phoenix.

You can witness the destiny of entire nations in the life of a single individual and the best example of this Armenian phoenix-like spirit is the life of Yousuf Karsh.

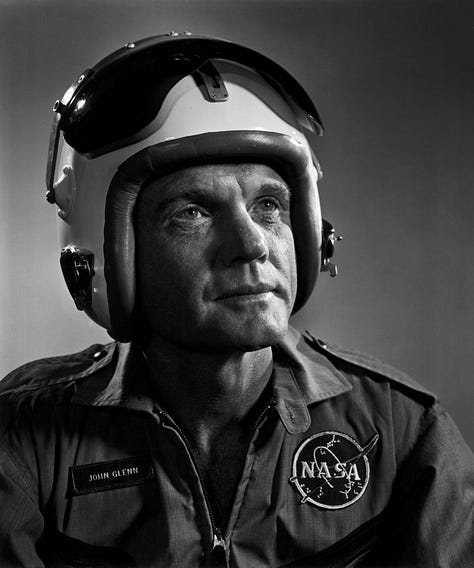

By the time he died in 2002, at the age of 93, Karsh was known for his iconic portraits of Winston Churchill, Albert Einstein, Audrey Hepburn, Ernest Hemingway, Walt Disney, Queen Elizabeth II and countless others. An impressive career for a man who was a refugee. At just thirteen, he was forced to leave his hometown of Mardin to escape the horrors of the Armenian Genocide unfolding in the Ottoman Empire.

“It was the bitterest of ironies that Mardin, whose tiers of rising buildings were said to resemble the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and whose succulent fruits convinced its inhabitants it was the original Garden of Eden, should have been the scene of the Turkish atrocities against the Armenians in 1915.”

~ from Yousuf Karsh’s Memoirs

How did a boy whose father was illiterate—a teenager whose family had to rebuild their lives from nothing—grow into the man behind some of the most iconic portraits of the world’s most famous figures?

My portrait of Winston Churchill changed my life. I knew after I had taken it that it was an important picture, but I could hardly have dreamed that it would become one of the most widely reproduced images in the history of photography.

~ Yousuf Karsh in 1941

How Karsh Plucked the Cigar Out of the Mouth of Winston Churchill

In 1941, Winston Churchill visited Washington and then stopped in Ottawa for a meeting with the Prime Minister Mackenzie King.

King knew there was one more essential guest for the event: Yousuf Karsh, Canada’s most celebrated portrait photographer and a legend on the global stage.

When Karsh turned on the floodlights in the room, Churchill started growling: ‘What’s this, what’s this?’ Nobody dared to step in to explain, except Karsh: ‘Sir, I hope I will be fortunate enough to make a portrait worthy of this historic occasion.’

Churchill, in his witty manner, replied: ‘Why was I not told?’. He then pulled out of one his fresh cigars, lit it up, and said: ‘You may take one’. Karsh trembled at the sight of the cigar. This was the photographer’s worst nightmare.

I held out an ashtray, but he would not dispose of it.

I went back to my camera and made sure that everything was all right technically. I waited; he continued to chomp vigorously at his cigar. I waited. Then I stepped toward him and, without premeditation, but ever so respectfully, I said, ‘Forgive me, sir,’ and plucked the cigar out of his mouth.

By the time I got back to my camera, he looked so belligerent he could have devoured me. It was at that instant that I took the photograph.

The Times newspaper would later describe this iconic portrait:

“Churchill’s scowl in the photo, which came to symbolise British defiance against Nazi Germany, was a result of Karsh’s decision to remove the prime minister’s cigar from his mouth.”

One doesn’t have to be an expert on Churchill to know how much he loved his cigars (and his drinks). Only Karsh, a master portraitist, would have had the audacity to remove a cigar from the mouth of a man who cherished them above all else.

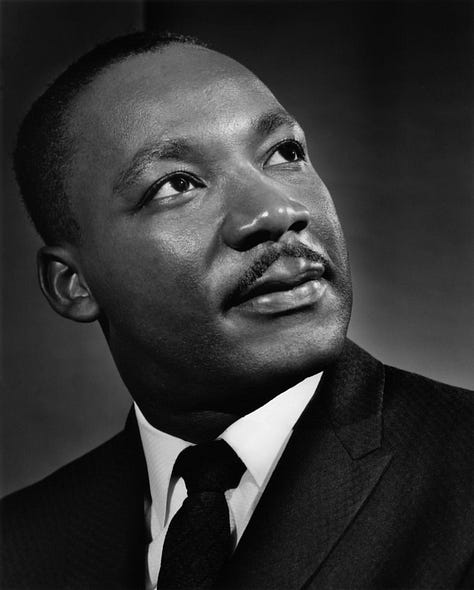

“What would the world be like were another atomic bomb to be dropped Mr. Einstein?”

The world watched in shock as atomic bombs were being dropped on the 6th of August 1945. For Karsh, who was familiar with human cruelty from an early age, the consequences of this tragedy were not as shocking as for the rest of humankind.

While my grandmother and her six sisters escaped death by fleeing northeast from their hometown of Van, Karsh’s family sought refuge in a camp to the southeast.

This was in 1922; he and his family hid themselves in a Kurdish caravan that was headed to a refugee camp in the Syrian city of Aleppo. Karsh’s sister contracted typhus and ‘in spite of my mother’s gentle nursing,’ she passed away never reaching the safety. It took them a month to reach Aleppo and every single day they worried that their caravan might be stopped by an Ottoman convoy and they could be killed just because of their Armenian blood.

Young Yousuf almost lost his life when he was caught away from the caravan by a Turkish soldier while drawing ‘a sketch of piled-up human bones and skulls, the last bitter landmark of my country.’ He writes that his father’s last silver coin went to bribing the Turkish soldier to keep his mouth shut.

When you witness the skulls and bones of your own people lying in the desert at the age of 13, you look differently at human cruelty. That is why what happened to Japan in 1945 was not as terrifying to Karsh, he saw, once again, that human cruelty can be infinite.

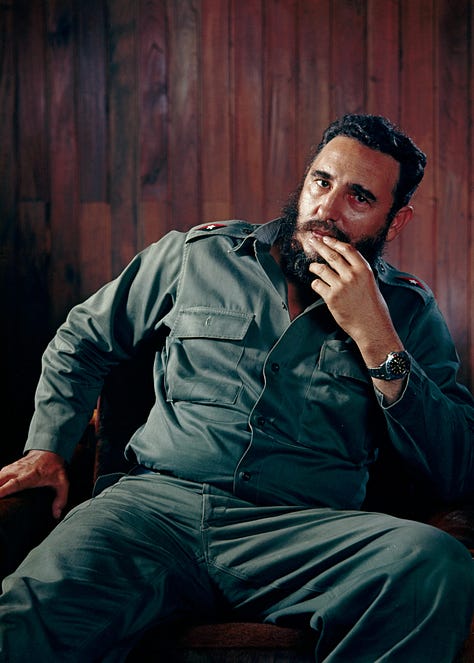

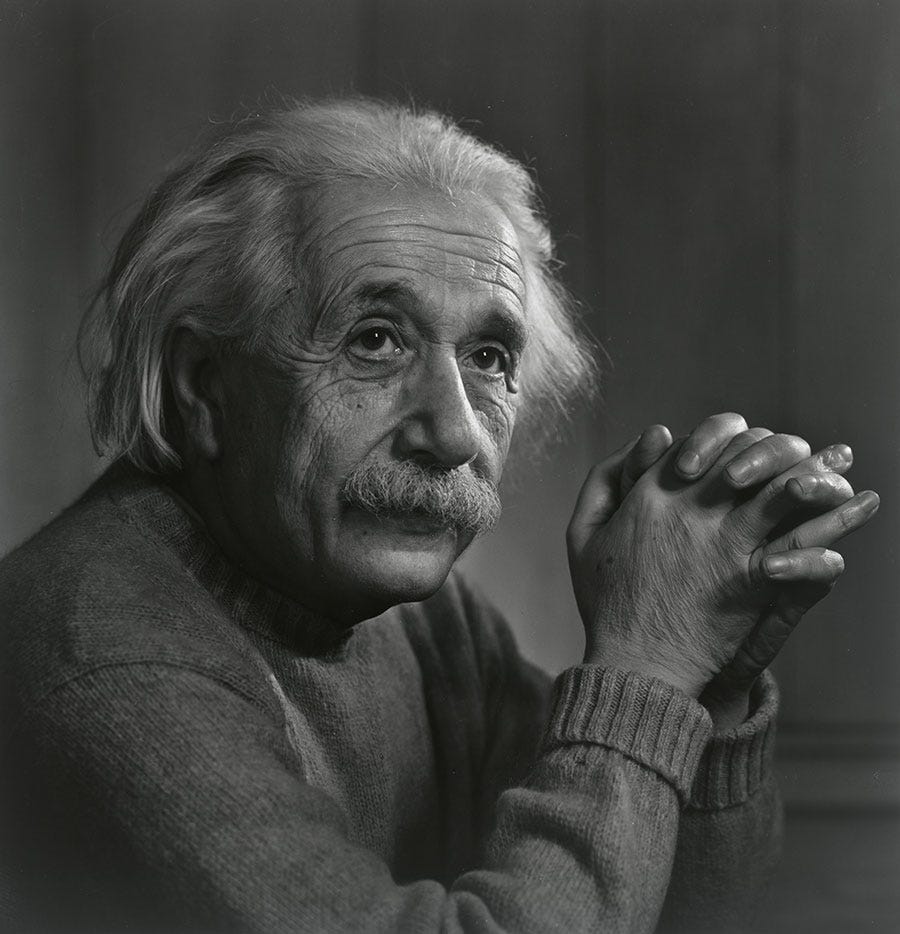

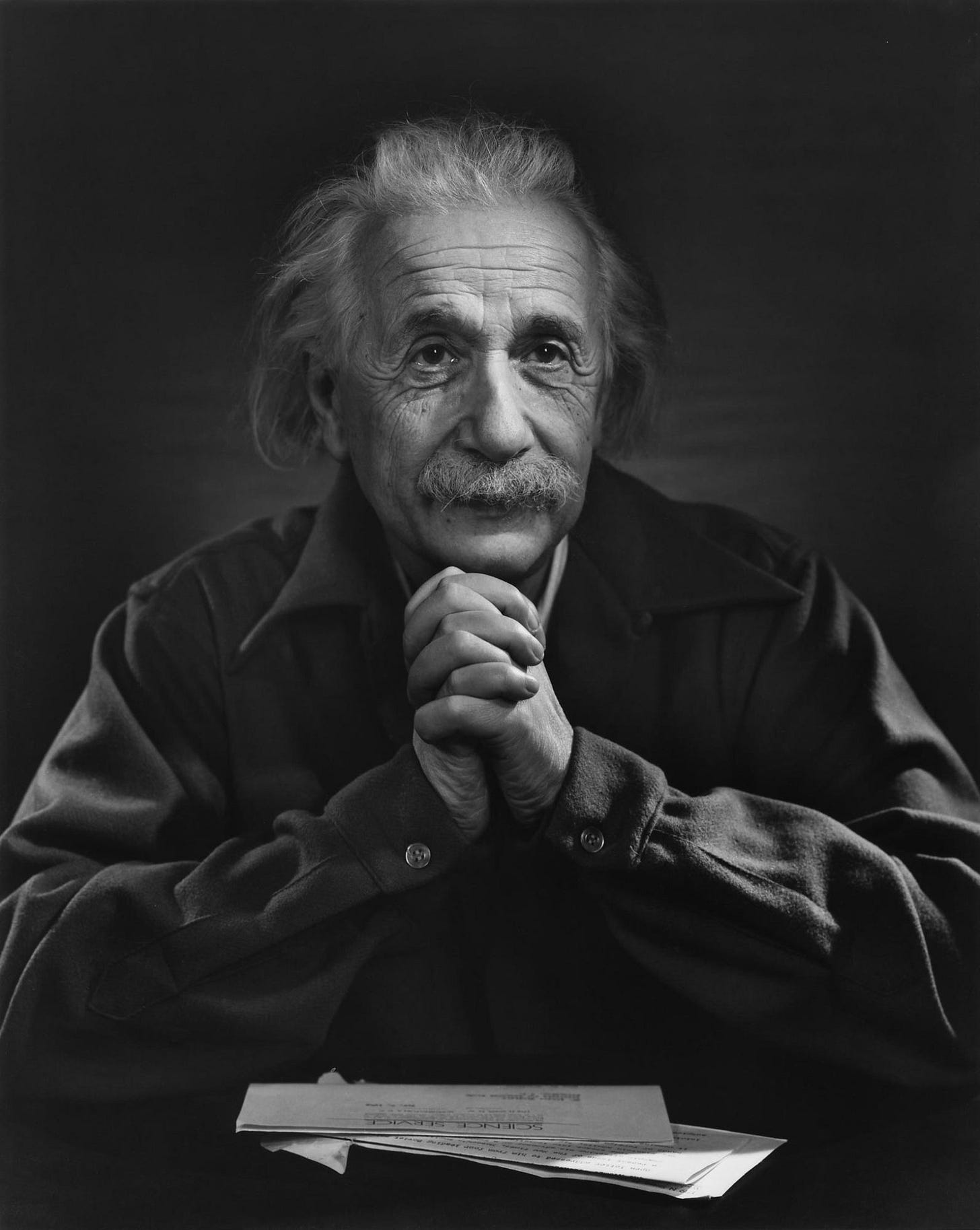

In 1948, Karsh went to the Institute of Advanced Study at Princeton and met the great Albert Einstein. “I found Einstein a simple, kindly, almost childlike man, too great for any of the postures of eminence. One did not have to understand his science to feel the power of his mind or the force of his personality. He spoke sadly, yet serenely, as one who had looked into the universe, far past mankind’s small affairs.”

Einstein, who himself fled Nazi Germany and dedicated himself to saving as many lives as possible, was perhaps one of the few who could truly grasp what it means to be hated and targeted for death solely because of one’s heritage.

When Karsh asked him “what the world would be like was another atomic bomb to be dropped” Einstein replied, “Alas, we will no longer be able to hear the music of Mozart.”

Sophisticated Vulnerability

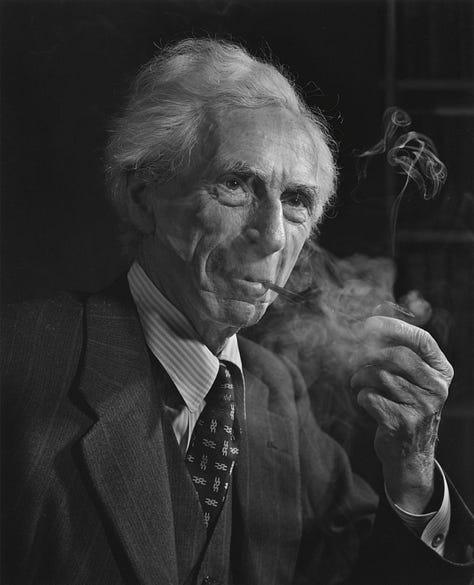

There is a brief moment when all there is in a man's mind and soul and spirit is reflected through his eyes, his hands, his attitude. This is the moment to record.

~ Yousuf Karsh

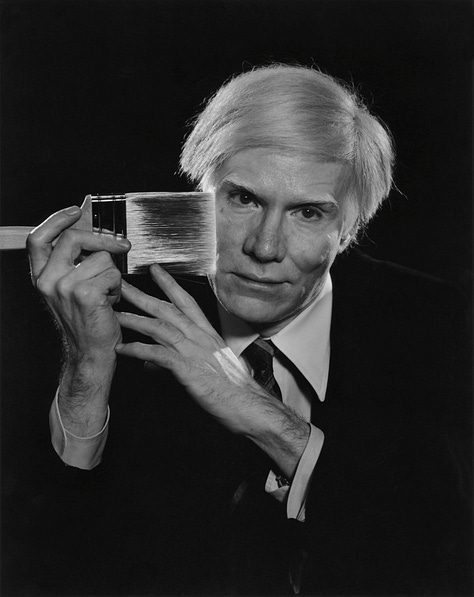

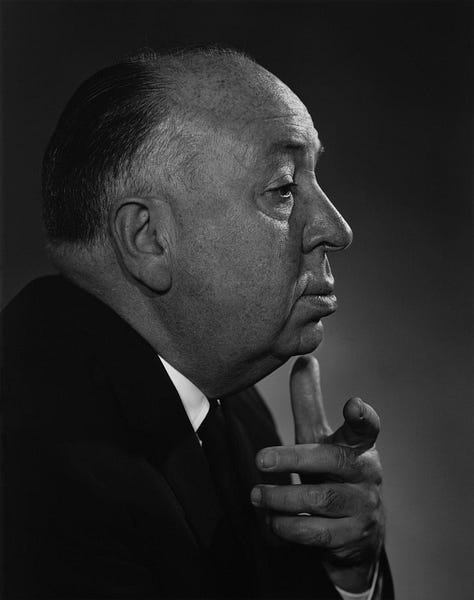

Whether it was Churchill, Einstein, Bogart, or Cocteau, what set Karsh’s portraits apart was their ability to peer into the very souls of his subjects, capturing something no one else could.

His photographs of Audrey Hepburn and the Queen Elizabeth II are particularly unique in their kind for they reveal the mind and the spirit of these exceptional women.

The trouble with photographing beautiful women is that you never get into the dark room until after they've gone.

~ Yousuf Karsh

Photography is all about the play of shadows and light, and the problem with beauty is that it shines from wherever you look. A photographer, like any artist, must choose the aspects of beauty that best unveil the essence of their subject’s personality.

When Karsh went to visit Audrey Hepburn in Hollywood in 1956 and commented on her sophistication and vulnerability, she told him all about her harrowing experiences during the Second World War. These were the wounds that never healed that Karsh knew he had to capture.

He knew what Hepburn meant since only five years ago he had experienced the same with Queen Elizabeth II.

The portrait that my reader sees above was taken before the Queen became the Queen. Karsh took portraits of the royal family several times throughout his career, but this portrait of Elizabeth II differs from any other photograph since it was taken six months before her father’s death.

She is light, innocent, and relaxed. The burden of the crown hadn’t yet fallen suddenly on her shoulders. She does not yet know what will happen soon.

How different are her mind and soul (the two elements that Karsh tried to capture in his portraits) in comparison to the picture he took a decade and a half later in 1966.

We know it is the same woman in each of these photographs by the way they look but not by their spirit. This is the magic of a portrait taken by Karsh, he shows the viewer not the way one looks, but the way they are.

What is the meaning of life Mr. Karsh?

In the safety of Aleppo, Syria, my father painstakingly tried to rebuild our lives.

Only those who have seen their savings and possessions of a lifetime destroyed can understand how great were the spiritual resources upon which my father must have drawn.

Despite the continual struggle, day after day, he somehow found the means to send me to my Uncle Nakash, and to a continent then to me no more than a vague space on a schoolboy’s map.

Karsh’s phrase “spiritual resources” perfectly encapsulates why I chose the phoenix as a mythical symbol of Armenia. It is from this deep spiritual wellspring that a nation, uprooted and scattered, gathers its strength to rebuild, to breathe anew, and to create once more. It embodies the indomitable power of the spirit—the resilience to witness a garden, nurtured for decades and founded by ancestors centuries ago, reduced to ashes, yet still possess the courage to plant grape seeds again.

The Greek historian Plutarch in his biography of Coriolanus once wrote:

It is only worthless men who seek to excuse the deterioration of their character by pleading and neglect in their early years.

It is in the nature of an Armenian immigrant to love his adopted land. The gratefulness for safety, for being allowed to rebuild your life again, the acceptance and kindness never leave us. It was so for Karsh. Canada was kind to him, and he was not going to blame his misfortunes on the unfair cruelty he experienced just four years ago.

‘My first day at Sherbrooke High School proved a dilemma for the teachers—in what grade did one place a seventeen-year-old Armenian boy who spoke no English, who wanted to be a doctor, and who came armed only with good manners? — the school was for me a haven where I found my first friends.

My formal education was over almost before it began, but the warmth of my reception made me love my adopted land.’

His Uncle George Nakashian (Nakash) gifted him a Kodak Brownie camera that changed young Yousuf’s life’s ambitions completely. He came to Canada with the desire to become a doctor, but the longer he spent with a little Brownie camera, the more he realised that his true passion was photography.

At school, he used to photograph landscapes and send them as gift cards to his friends. One of his classmates secretly entered a competition on Yousuf’s behalf. To his amazement, Yousuf won the first place and got fifty dollars as a gift. He gave ten dollars to his friend and sent the rest to his struggling family in Aleppo.

‘No talent ever dies’ wrote Seneca, and young Yousuf’s talent was becoming noticed in the local photo-studios and his career began to rise, as we have seen, to inscrutable heights.

Light and shadows. Light and shadows. All the essence of photography is light and shadows.

In his final years when he was interviewed for a magazine, Karsh was asked a terribly difficult question:

What is the meaning of life Mr. Karsh?

Karsh replied: ‘The meaning of life, like in photography, is all about light’

In another interview, he said:

Light thinks it travels faster than anything but it is wrong. No matter how fast light travels, it finds the darkness has always got there first, and is waiting for it.

Karsh was a photographer-philosopher, unique in his kind, seeing meaning and capturing it before it shuts from our eyes forever.

In 1957, Karsh went to see Ernest Hemingway, who already was at the peak of his fame.

“I expected to meet in the author a composite of the heroes of his novels. Instead, in 1957, at his home Finca Vigía, near Havana, I found a man of peculiar gentleness, the shyest man I ever photographed - a man cruelly battered by life, but seemingly invincible.”

It might seem that Karsh photographed celebrities simply because of their fame, but such an assumption would be far too superficial. The figures he took pictures of were not selected for the sake of their fame but because of how darkness shaped their character.

Each of us carries a light within, and the places we choose to illuminate with it ultimately define who we are. Karsh’s life began with darkness, but it is in the spirit of the phoenix to plan his revival as he is reduced to ashes. He wrote about the times he witnessed the genocide that took the lives of his uncles, cousins, and neighbours:

My recollections of those days comprise a strange mixture of blood and beauty, of persecution and peace.

When the world drowns itself in darkness, it is your duty to shine the light that you carry within.

As I wrote at the start ‘we can witness the destiny of entire nations in the life of a single individual’ and in the biography of Karsh, we have seen the destiny of Armenians. He became a Canadian citizen at the age of 18, but until old age of 93, he claimed to be an Armenian in the service of Canada. He preserved his ancestral soul.

The soul that draws from the infinite well of the spiritual strength. The soul that loses everything and rebuilds again. The soul that shines light despite witnessing darkness. The soul that never stops, never pauses, never looks back in contrast to Orpheus who went to the underworld but continues on. That is the soul of the phoenix.

As always confide tibimet.

As the others have said, this is beautiful, Vashik. Your writing is becoming more and more impressive with every post.

A beautifully written piece about a man who did indeed capture the soul of those he photographed. Each picture is a work of art. I knew nothing of Karsh's life until I read this, and I shall look at these portraits in a fresh light in the future. Thank you!