Breaking the Ice Within ❄️: The Line Between Good and Evil Passes Through Every Heart

(Inferno, Canto XXXII): On Dante, Solzhenitsyn, and the Line Through the Heart

The face is the mirror of the mind, and eyes without speaking confess the secrets of the heart.

~ St. Jerome

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

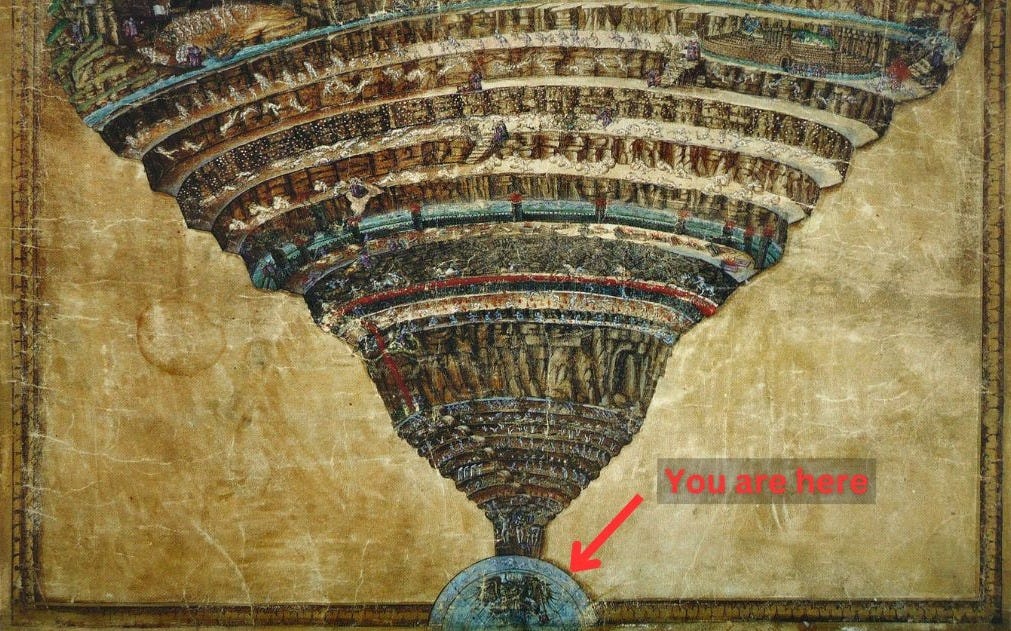

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Thirty-second Canto we arrive in Ninth Circle and encounter the frozen lake Cocytus and the Traitors to family and party. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Dante and Virgil arrive in the Ninth Circle of Hell - The frozen lake of Cocytus - The first ring, Caïna, traitors to kindred and family - Heads of sinners above the level of their bodies frozen in ice - The second ring, Antenora, traitors to country, city, and party - Dante witnesses one traitor feasting on the skull of another.

Canto XXXII Summary:

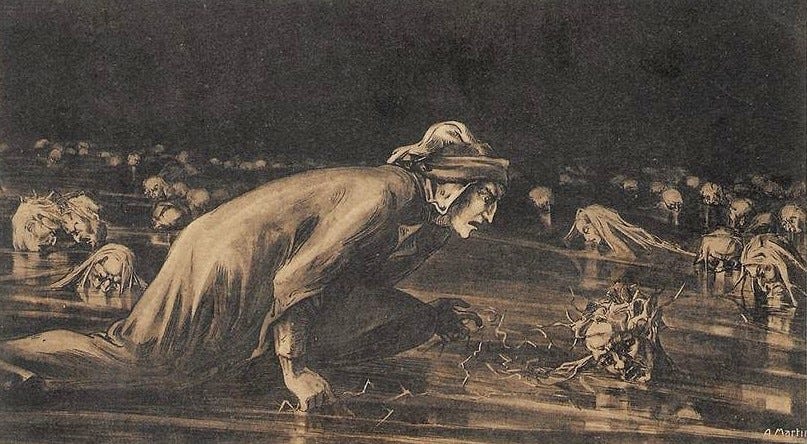

We have arrived into the deepest pit of Hell, into the outermost of the four rings of the Ninth Circle, the frozen lake of Cocytus. Caïna, the outermost ring, contains traitors to their kindred.

Next is Antenora, which holds traitors to country, city, and party. Third will be Ptolomea, traitors to their guests, and finally, the very last — the very depth of malicious sin — is Judecca, traitors to their lords and benefactors.

Beneath the clamour, beneath the monotonous circling, beneath the fires of Hell, here at the centre of the lost soul and the lost city, lie the silence and the rigidity and the eternal frozen cold. It is perhaps the greatest image in the whole Inferno.1

Not only are they at the bottom of hell, not only are they in the depths of the earth, but they are crushed by the weight of being the very center of the entire known universe; in the Ptolemaic system under which Dante lived, the earth was the center of the cosmos, the “base of all the universe” (XXXII.8). To put the sights of this realm into verse is the harshest of tasks, and even Dante’s genius feels muted as he tries to undergo the challenge.

Dante invokes the Muses again2 as they enter into this new and unknown realm, especially after leaving the routine familiarity of the ten trenches of the Eighth Circle. So terrible are the sights witnessed, that he needs their aid to even express the horrors.

The Muses — those nine goddesses of the arts — also helped Amphion, that famed builder of Thebes, whose music charmed the stones to place themselves in position:

While men still roamed the woods, Orpheus, the holy prophet of the gods, made them shrink from bloodshed and brutal living; hence the fable, that he tamed tigers and ravening lions; hence too the fable that Amphion, builder of Thebes’s citadel, moved stones by the sound of his lyre, and led them whither he would by his supplicating spell.

Horace, Ars Poetica 391-396

The inhabitants of this Ninth Circle, the lowest of sinners, both morally and literally in their placement in the center of the earth, would be better off as animals, unable to sin so maliciously and unaware of the horror they now existed in.

O rabble, miscreated past all others,

there in the place of which it’s hard to speak,

better if here you had been goats or sheep!

XXXII.13-15

Now the stage is set, and we can meet those who dwell here.

Dante and Virgil are still where the giant Antaeus had placed them in the well of the Ninth Circle, and as Dante gazed up from whence they had come, a voice calls out for caution in his step. Commentators old and modern have debated the identity of this speaker; some say Virgil, others say it was an anonymous sinner, others still say one who will speak later in the Canto.

It is this voice that shifts Dante’s attention from the wall of the well to the scene spread out before him;

At this I turned and saw in front of me,

beneath my feet, a lake that, frozen fast,

had lost the look of water and seemed glass.

XXXII.22-24

Nothing on earth, no thickness of ice, could compare to the icy density of this lake; even were mountains to fall onto it, it would not yield.

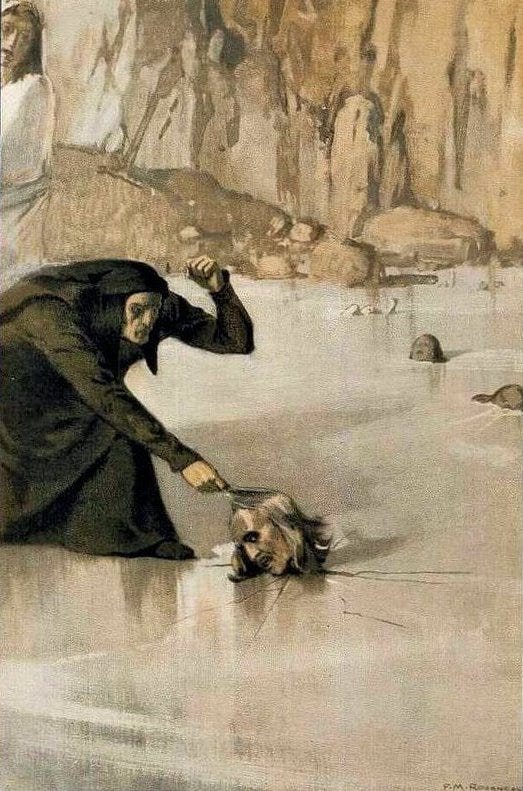

The imagery of frogs with their heads above water, last seen with the barrators in the fifth bolgia of the Eighth Circle3 is in force here; but instead of being able to dive beneath the waters away from punishing demons, here they are encased, frozen, and immobile. These sinners are in ice up to their necks, colored a leaden, livid blue with the cold, heads bent down, teeth chattering, tears falling frozen to the ice.

At Dante’s feet are two figures so close together that their beings are mingled to their very hair, and as their faces upturn to look at him, their tears freeze on their faces, increasing their bond and locking them together even more tightly.

These are the brothers Napoleone and Alessandro degli Alberti, the former of the Ghibellines and the latter a Guelf, who killed each other in a fight over the inheritance of their fathers estate, one Alberto degli Alberti of Mangona. The inheritance was rightfully Alessandro’s.

Their locked position emphasizes the contrapasso of their crime as they are now frozen in an eternal, icy embrace as punishment for their hatred and killing of each other. All this is told to Dante by another sinner, whose head hangs down, his ears frozen off, who names the realm as Caïna. These traitors of kindred are named after Cain, the first murderer, who killed his brother Abel:

Cain brought of the fruit of the ground an offering unto the Lord. And Abel, he also brought of the firstlings of his flock and of the fat thereof. And the Lord had respect unto Abel and to his offering: But unto Cain and to his offering he had not respect. And Cain was very wroth, and his countenance fell.

And Cain talked with Abel his brother: and it came to pass, when they were in the field, that Cain rose up against Abel his brother, and slew him. And the Lord said unto Cain, Where is Abel thy brother? And he said, I know not: Am I my brother's keeper? And he said, What hast thou done? The voice of thy brother's blood crieth unto me from the ground. And now art thou cursed from the earth, which hath opened her mouth to receive thy brother's blood from thy hand. Genesis 4:3-5; 8-11

Also to be found in this realm would be Gianciotto Malatesta, the killer of Francesca and Paolo, the lovers from Inf. V.107

Love led the two of us unto one death.

Caïna waits for him who took our life.

Inf. V.106-107

This yet to be named speaker tells Dante that no one deserves this realm more than the two brothers Alessandro and Napoleone, and proceeds to list others who are there, of whom the brothers are the most deserving.

This includes the death of Mordred, nephew - and by some accounts, the son as well - of King Arthur.

King Arthur “came at him as directly as he could, struck him with all his strength so hard that he broke the chain mail of his hauberk and split his body with the steel of his sword. The story recounts that after the sword thrust, a ray of sunlight passed through the wound so visibly that Girflet saw it.”4

It also included Focaccia, a nickname of Vanni de’ Cancellieri, a white Guelph who is “said to have cut off the hand of one of his cousins and cut his uncle’s throat, and thus to have started the family feud from which the Black and White Guelph factions had their origin.”5

The last sinner mentioned by the speaker, he with the frozen ears, is Sassol Mascheroni, famed in Tuscany for his notorious murder of his kinsman in order to gain an inheritance. For his crime, “he was rolled through the streets of Florence in a cask full of nails and afterward beheaded.”6

The speaker finally identifies himself as Camicion de’Pazzi, of whom little is known but that he murdered one of his relatives, Ubertino. Camicion, however, is awaiting one named Carlin, who will be placed in the next ring of Circle Nine - he had not yet arrived - those who were traitors to country, city, or party. Carlin, or Carlino de’ Pazzi, betrayed for a bribe a fortress in Pistoia to the enemy Florentines, causing the killing and capturing of many Florentine exiles who were in refuge there for safe haven.

A cold and cruel egotism, gradually striking inward till even the lingering passions of hatred and destruction are frozen into immobility - that is the final state of sin.7

Here there is a shift to the next ring of the Ninth Circle, from that of Caïna to that of Antenora, the realm of traitors to country, city, and party.

This realm is named for Antenor, a Trojan who in certain legends was said to have betrayed Troy to the Greeks. He was called a “treacherous Judas,” and was also thought to have been involved in the theft of the Trojan Palladium, the statue on which their protection depended. None of these are found in Virgil or Homer, but in later accounts.

And while we were advancing toward the center

to which all weight is drawn - I shivering

in that eternally cold shadow - I

know not if it was will or destiny

or chance, but as I walked among the heads,

I struck my foot hard in the face of one.

XXXII.73-78

This sinner whom he kicked lashes out in anger at Dante, as if he is not being punished enough for his role in the battle of Montaperti, to now face additional abuse. Dante asks Virgil to wait so he can find out more, and promises the sinner fame in his poetry if he will share his story, but this sinner does not want his name to be known and refuses to speak. Dante demands an answer, and his vehemence is surprising; Sayers notes about this interaction that “treachery is cruel, and cruelty calls forth cruelty”,8 noting Dante’s similar reaction in Inf. VIII.37-42 to Filippo Argenti.

This unnamed sinner refuses to submit, no matter the abuse, but is foiled by another calling out his name; it is Bocca degli Abati, whose actions cause the terrible defeat of the Guelfs at the Battle of Montaperti, in which he cut off the hand of he who held their standard, causing confusion among the ranks, which led to their defeat.

Bocca, in his rage at being recognized, goes into a litany of the other sinners there with him in Antenora, as if listing the inventory of their faults to make his own seem less, especially now that Dante knows his name and will include him in his report.

Bocca tells of the Ghibelline Buoso da Buera, a traitor to his party, who allowed the enemy French army of Charles of Anjou through on their way to Naples on his watch; he tells also of Tesauro dei Beccheria of Pavia, a papal legate who acted in conspiracy with exiled Ghibellines, of Gianni de’ Soldanier, a Ghibelline who joined in opposition to them during a rebellion, of Ganelon, the traitor against Charlemagne in the Song of Roland who caused the death of the leading knights of Charlemagne’s army, and finally of Tibbald, another Ghibelline traitor.

After these accounts of traitors to their city and party, we encounter one of the most memorable — and one of the most horrific — images of the whole Divine Comedy.

A terrible sight presents itself, of two souls frozen together in a single hole, the one gnawing upon the head of the other, the two joined together in a terrible, unholy union; we will learn their story in Canto XXXIII.

Even this however, has its counterpart on earth, in the awful story of Tydeus. He who overcame Menalippus in battle during the war of the Seven Against Thebes. Outraged over his own mortal wound inflicted by Menalippus in their fighting, Tydeus ordered, to the horror of all, the head of the still living Menalippus to be cut off and brought to him. He proceeded to gnaw it in just such a way as does this sinner to the one in his icy embrace in Hell.

Tydeus gazed at him

And, mad with joy and anger, when he saw

His gasping mouth, his eyes, and recognized

His handiwork, he told them to cut off

His enemies grim head and give it to him.

Taking it in his hand, he studied it,

Gloating to see it warm and the wild eyes

Still wandering, unsure of death’s firm grip.

He was content, poor soul: Tisiphone,

Avenging, called for more. And now Pallas

Had come, her father mollified, to bring

That sad heart deathless fame. And him she saw

Drenched in the foul filth of the shattered brain,

His jaws polluted with live human blood,

Nor could friends wrench it from him.

Statius, Thebaid VIII.754-768

Dante swears an oath that he will repay the as yet unnamed sinner if he would share his story.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

"If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.

~ Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

We all like to believe that, had we been in Oskar Schindler’s place, we would have made the same choice, that we would have rescued innocent souls from certain, yet avoidable, death.

But the reality is far less flattering.

The truth is, it’s far more likely that we would have chosen to be a concentration camp guard than the rare soul who defied the system to save others.

“If only it were all so simple,” wrote Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. “If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

What is it, then, that makes us choose one side of that line over the other?

Why do some, like Oskar Schindler or Franz Jägerstätter9, choose the good, against all odds, while others willingly, even eagerly, choose evil?

The truth is, no one sees themselves as a villain. No soul rises in the morning, and while brushing their hair, is already plotting whom they will harm that day.

The journey to virtue begins with recognition of evil within ourselves.

“Why do you so mirror yourself in us?” — says the damned Pazzi from beneath the ice to Dante. I would dare to suggest that this line is, perhaps, the most profound utterance made by any of the damned throughout the Inferno10. Pazzi sees that Dante looks at him not merely to recognise evil in others, in the damned souls like Pazzi himself, but with an intensity that betrays something deeper.

In each of the condemned, Dante sees a reflection of his own nature. It is as if he looks beyond that line where evil dwells within himself. As he journeys through Hell, he is not just witnessing the punishments of the wicked, he is confronting the shadow within his own heart.

This is why I believe Dante loses consciousness at the start of the Inferno. It is not merely the horror of the damned that overwhelms him. It is the shock of facing himself, of confronting the nature within him, and the terrifying vision of who he might become should he choose the wrong path.

Like Solzhenitsyn wrote, the line between good and evil does not run between people, but through the heart of each one of us. Dante’s gaze is that of a man who sees in every sinner a mirror held up to his own soul.

To prevent evil, one must first be able to recognise it. Those who commit evil often do so not out of deliberate malice, but because they lack the ability to discern what is truly good from what is truly evil. 11

In this canto, both I, and I suspect you, my reader, were startled to witness Dante seize one of the sinners, Bocca degli Abati, by the hair. You will recall that, until now, Dante has wavered between pity and scorn for the souls he encounters. Yet here, something shifts.

One might think - as some respected commentators do - that when Virgil rebukes Dante for feeling pity toward the damned, he does so because Dante is questioning Divine justice. This is only partially true. Dante’s pity is not solely for the souls before him; it is also for the part of the sin he recognises within himself. It is as if he is saying, “Perhaps this is not entirely bad… perhaps I should keep this sinful part of myself.”

When Dante grabs Bocca by the hair, he is not merely acting violently toward the damned—he is being firm with himself. Virgil has taught him well: one cannot hesitate when confronting evil; one must learn to discern clearly.

The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing, but perhaps we should add that evil also triumphs when individuals fail to discern between good and evil in the first place. It is in hesitation that evil triumphs.

II. Philosophical Exercise: Do not betray yourself for nothing. The cure of trust.

Your worst sin is that you have betrayed yourself for nothing.

~ Dostoyevsky, Crime and Punishment

Treachery and betrayal, in Dante’s vision, is lack of love, lack of trust, it is death itself. Dostoyevsky’s quote12 is particularly suitable here, for when we betray ourselves, a part of ourselves, we deprive it of oxygen; betraying ourselves means we kill what we could have become.

“Trust yourself,” says eternal wisdom, or confide tibimet in Latin, a phrase that holds its roots in Virgil’s Aeneid, where Aeneas, in a moment of peril, urges his companions: “Durate, et vosmet rebus servate secundis” (“Endure, and preserve yourselves for better days”).

In the same way as a human being disintegrates and destroys themselves when they lose trust in their own soul, so too do relationships, families, and entire societies collapse when trust, that invisible thread that binds them, is severed.

The circle of traitors is divided into four frozen zones—Caina, Antenora, Ptolemea, and Judecca. In this canto, we descend into the first two: Caina, where those who betrayed family and kin are punished, and Antenora, the realm of political treachery- betrayal of party or country.

Is it necessary to remind my reader that every soul we encounter here has caused death through their treachery?

Antenor, the grandson of King Priam of Troy, betrayed his own city, first, by urging the return of Helen to Menelaus, then by assisting the Greeks in bringing the Trojan Horse within the city walls.

We meet brothers who murdered one another over inheritance, their blood forever frozen in the lake they helped to form.

Soon, we will meet Malatesta - the very one responsible for the death of Paolo and Francesca, whose tragic love moved us earlier in the journey.

Treachery destroys trust. The collapse of trust brings disintegration.

And life, once warm, breathing, in motion, freezes into stillness, into death.

This is why every soul we find here has, in some way, caused death: not by passion or impulse, but by the cold calculation of betrayal.

In this circle, more than anywhere else, I would like to finish with the phrase my reader has seen many times before here at

- Confide tibimet (Trust yourself)This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Dante as Ulysses

But may those ladies now sustain my verse

who helped Amphion when he walled up Thebes,

so that my tale not differ from the fact.O rabble, miscreated past all others,

there in the place of which it’s hard to speak,

better if here you had been goats or sheep!(Mandelbaum, lines 10-15)

Ulysses in Dante’s interpretation of the famous character abandons his family to continue his journey and, according to Dante, crosses the Pillars of Heracles, the metaphorical area which no mortal should cross, an area reserved for immortals only.

One cannot deny that we get the same feeling that Dante is attempting the same here in his opening verses. He is at loss for words, and invokes the Muses once again to be able to describe what no mortal has yet seen.

In contrast to Ulysses however, Dante’s journey does not seem to be a transgression of the Divine will, since his journey was granted from above.

Babel, Giants and Failure of Speech

The same opening verses also suggest another connection, a bridge between the realm of giants and the realm of the treacherous.

My reader might recall that in the previous canto, the giants were unable to speak. They had lost the power of language.

The opening verses of this canto, in which Dante himself seems momentarily lost for words, mirror that very state. It is as if, after encountering such immense and mute beings, he too must pause and recuperate before continuing his descent.

The Inferno of Ice and Fire

When we imagine Hell, we often picture unbearable heat - scorching flames and burning flesh. Fire is the element that comes to mind. And yet, in this final circle, the realm of the worst sin - the sin that contains within it all the others we have encountered - the dominant element is not fire, but ice.

The sinners are frozen in a mirror-like lake, condemned to gaze at their own reflections for eternity. The ice does not just imprison their bodies - it forces them into an endless confrontation with themselves. Here, in the deepest circle of Hell, the traitors are given no company but their own. They stare at mirror-like ice to see their own reflection. Their punishment is to spend eternity face-to-face with the one whom they betrayed: themselves.

The fire, as a punishment in the previous circles, made the damned move, uncontrollably in an attempt to escape the pain. Ice however, equally terrifying and torturous, freezes the damned; they can no longer move.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

E un ch’avea perduti ambo li orecchi

per la freddura, pur col viso in giùe,

disse: «Perché cotanto in noi ti specchi?…

“And one, who had by reason of the cold

Lost both his ears, still with his visage downward,

Said: “Why dost thou so mirror thyself in us?”(Longfellow, lines 52-54)

Sayers Hell 275

See Inf. II.7

Inf. XXII.25-27

Singleton, Commentary on Inferno 590, from Malory’s Morte d’ Arthur

Sayers 276

Singleton 591

Sayers 275

Sayers 277

If you haven’t seen Terence Malick’s film A Hidden Life, which explores the story of Franz, please, I beg you, watch it.

I do it humbly and subjectively.

Hannah Arendt’s The Banality of Evil is a great glimpse to explore this topic.

I am assuming there are many Dostoyevsky fans in here and they recognised Raskolnikov’s and Sonia’s theme. While two masterpieces are different the meaning of it is applicable to both, though in different contexts.