Can a Civilisation Endure Once It Has Lost its Religion?

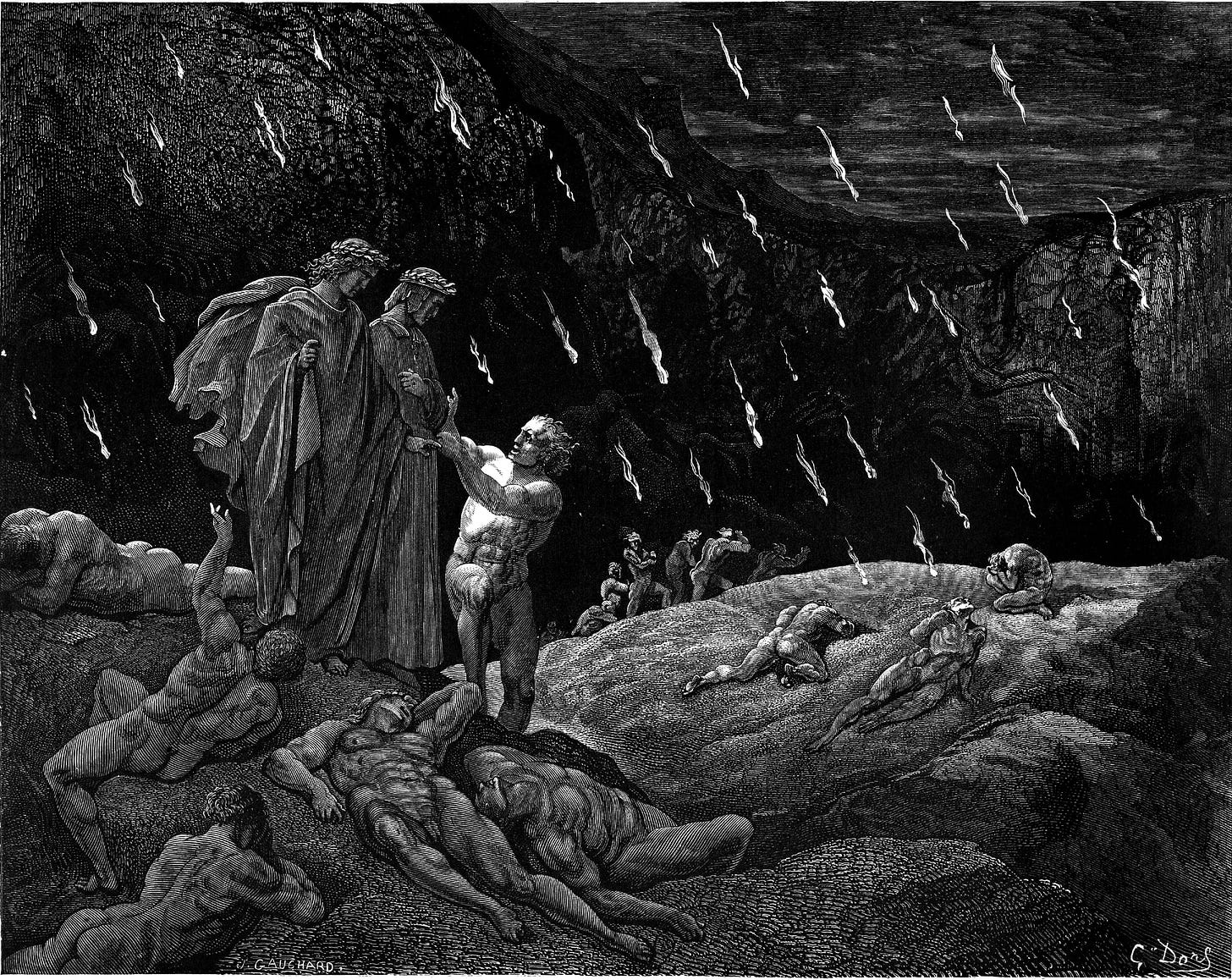

(Inferno, Canto XIV): Capaneus, The Old Man of Crete and Violence Against God.

Civilisations that lose all religious cohesion either disintegrate into chaos or are absorbed by another culture.

~ A Study of History by Arnold Toynbee (1947)

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Fourteenth Canto we enter the burning sands of Violence against God. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Seventh Circle, Third Ring - Between the wood and the burning sand - Those who were Violent against God - Blasphemers - The falling flakes of fire - The giant Capaneus - The Old Man of Crete and the Ages of Man - The origin of the rivers of Hell.

Canto XIV: Summary

The pilgrim finishes his action from the last Canto in the wood of the Violent against Self. He had been speaking with the unnamed suicide embodied in the plant, who had asked if they could pick up his broken branches and place them around his trunk. Dante obliged his fellow Florentine.

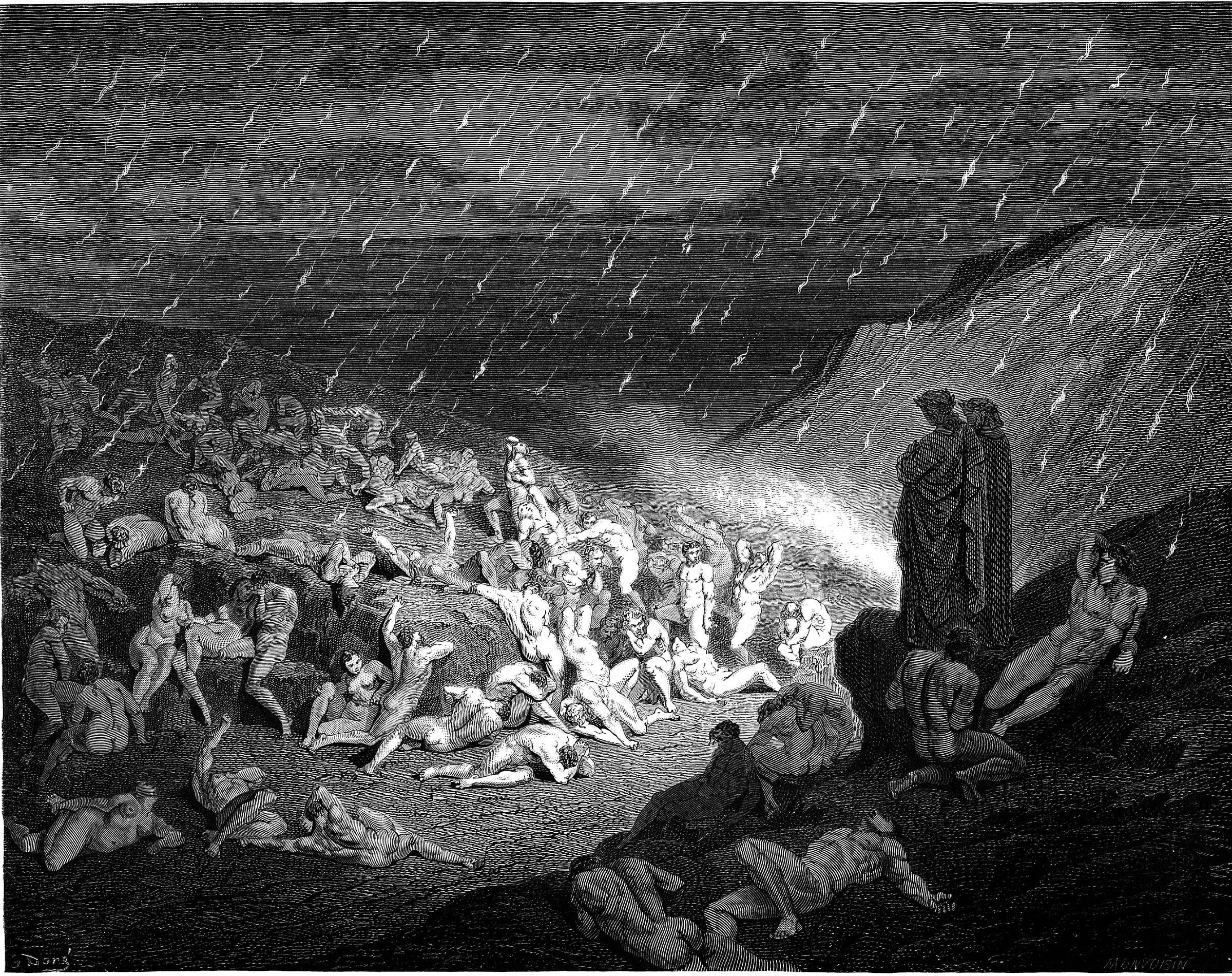

Dante and Virgil see a new punishment being enacted as soon as they crossed from the second into the third ring of the Seventh Circle, a wide stretching realm of sand encircled by the wood of the suicides, which itself was encircled by the river Phlegethon containing the Violent against Others. This realm of sand held “the sight of a dread work that justice had devised” (XVI.5-6); that contrapasso which represents a weighing of the scales. The sand was like that which Cato would have marched over in Libya during the Civil War with Caesar, and the sight was so moving that Dante called out to us, his readers, imploring us to take heed.

O vengeance of the Lord, how you should be

dreaded by everyone who now can read

whatever was made manifest to me!

XIV.16-18

Dante saw before him “flocks of naked souls” (XIV.19), all in different attitudes or positions upon the sand; some lying prone, some crouching, and others who walked about; this latter was the largest group. One commentator distinguished these three groups as those Violent against God, Art and Nature.1

Of all the different positioning of the suffering souls, they all had the same flakes of fire raining slowly down upon them. The souls tried to bat them away, but as the flakes landed, they kindled the sand and the heat then came from both above and below.

Just like the flames that Alexander saw

in India’s hot zones, when fires fell,

intact and to the ground, on his battalions,

for which-wisely-he had his soldiers tramp

the soil to see that every fire was spent

before new flames were added to the old;

so did the never-ending heat descend;

with this, the sand was kindled just as tinder

on meeting flint will flame--doubling the pain.

XVI.31-39

The 13th century De meteoris of Albertus Magnus describes Alexander’s account of the falling flames, although the source that Magus used is now considered of doubtful authenticity, based on letters from Alexander to Aristotle, his teacher.

Moreover, Alexander gives a remarkable description of it in a letter on the Wonders of India addressed to Aristotle. He says: ‘Fiery clouds fell from the sky like snow and he ordered the soldiers to stamp them down’2

Another source of the imagery of the falling flame comes from the Old Testament in the story of Lot fleeing the destruction of his city: “Then the Lord rained upon Sodom and upon Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the Lord out of heaven.”3 Dante asks Virgil about the giant in the distance who is unaffected by the fiery flakes. The soul heard Dante and answered, in his arrogance, that no matter how much Jove tries, he will never “have happy vengeance” (XIV.60) against him:

That which I was in life, I am in death.

Though Jove wear out the smith from whom he took,

in wrath, the keen-edged thunderbolt with which

on my last day I was to be transfixed;

or if he tire the others, one by one,

in Mongibello, at the sooty forge,

while bellowing: ‘O help, good Vulcan, help!’

just as he did when there was war at Phlegra-

and casts his shafts at me with all his force,

not even then would he have happy vengeance.

XVI.51-60

This is Capaneus, one of the Seven against Thebes of Greek myth, who was killed by Jupiter’s thunderbolt for his brashness toward the gods. Virgil rebukes him, his arrogance, and his violence toward the gods.4 Capaneus, stuck in his pride and refusing remorse, invokes many names in his speech; Vulcan was the blacksmith of the gods who was a god himself, also known as Hephaestus, who created the thunderbolts of Jupiter, and Mongibello is his forge, the volcanic Mount Etna.

Capaneus the Blasphemer is chosen as the particular image of Violence against God: he is an image of Pride, which makes the soul obdurate under judgment. The arrangement of Hell, being classical, allots no special place to Pride….but it offers a whole series of examples of Pride, each worse than the last, as the Pit deepens5

Virgil warns Dante to stay away from the burning sand, and to stay near the edge of the wood of the second ring.

In silence we had reached a place where flowed

a slender watercourse out of the wood--

a stream whose redness makes me shudder still.

XVI.76-78

This remnant of the Phlegethon is flowing as a trickling stream, out of the wood; Dante compares the red Phlegethon with the reddish waters of the Bulicame, a hot and sulfurous spring of which one portion was directed to the quarter of prostitutes, as they were prohibited from the public baths. The rivulet had banks and a bed of stones; this would be their path. Virgil says:

Among all other things that I have shown you

since we first made our way across the gate

whose threshold is forbidden to no one,

no thing has yet been witnessed by your eyes

as notable as this red rivulet,

which quenches every flame that burns above it.

XVI.85-90

Dante asks for the wisdom underlying this sentiment; “I begged him to bestow the food for which / he had already given me the craving” (XVI.92-93).

Virgil explains:

In the reign of Saturn in the Golden Age, on a blessed mountain called Ida, on the island of Crete, was the cradle for mighty Zeus upon his birth. His mother Rhea hid him there as his father Saturn had been devouring his children as they were born, due to a prophecy that he would be overthrown by one of his sons. The clamor of her servants to cover the baby Jupiter’s cries were from her nine servants of dance, the Corybants. This sounds like an idyllic place, but Virgil opens this bit of dialogue calling the land “devastated,” and that blessed mountain is now withered and old.

Within the mountain is the Old Man whose back is turned toward Damietta and who is gazing at Rome, as if at himself in a mirror. Damietta is a city in Egypt; the statue is facing away from the East, the old way, the pagan world of gods and goddesses. His gaze toward Rome is then the new way, the way of Christianity.

The Old Man’s head is of gold, his arms and chest are silver, from there down to his legs he is brass, and then his legs and feet are of iron; except his right foot, which is of clay, on which he places his weight.6 We will examine the symbolism of this figure more below.

All of these elements are cracked except for the gold, and from the cracks issue his tears, which gather below him, “and crossing rocks into this valley,” (XVI.115) form the rivers of Hell; the Acheron, the Styx, the Phlegethon. They run deep, and gather to form the frozen waters of Cocytus, which is the lowest and last of the rivers. Virgil says that he will not describe it as Dante will be seeing it in their journey (Inferno XXXIV).

Dante asks a simple question; if it is as Virgil says, then why is he just seeing this small rivulet? Virgil explains that since the architecture of hell is in these rounds, they did not circle the full round of each level, so Dante has not seen it all.7

If something new appears to us,

It need not bring such wonder to your face

XVI.128-129

But Dante is still confused. He asks where Phlegethon and Lethe are? Remember, that Phlegethon was not named in Canto XIII, so Dante is not yet identifying it by name. Virgil explains that Phlegethon was where they just saw the red and boiling river of blood, and that they have not yet encountered Lethe; that will be in another realm, in Purgatory, where souls are not being punished, but cleansed through repentance.

Virgil’s Lethe in the Aeneid served a different purpose; to cleanse the memory before being reborn on earth;

Who are the people who’ve crowded the banks in a giant formation?

Father Anchises replies: ‘They’re souls that are due second bodies:

So fate rules, and they’re drinking now from the waters of Lethe,

Draughts that will free them of care and ensure long years of oblivion’

Aeneid VI.712-715

Within these expositions they have not yet truly entered the third ring of the Seventh Circle, but were looking upon it from the edge of the wood. Now it is time for them to follow the path around the edge in safety, to see the souls cast down into the burning sands.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

~ Ozymandias, Percy Bysshe Shelley

I. Can a civilisation survive if it loses its religion?

Every book I call my “favourite” has come to me through a serendipitous encounter. Arnold Toynbee’s exceptional A Study of History is one such book—one that, I believe, is deeply connected to the meaning of this canto.

The central thesis of this masterpiece, a historical study largely forgotten today, is this:

'Civilisations are not static entities but dynamic organisms. They rise and fall based on their ability to respond creatively to their challenges. Civilisations grow, decline, break down, and either regenerate or disappear depending on how they handle challenges.

Nietzsche famously wrote that if an idea does not keep you awake at night, turning over and over in your mind, then it is not worthy of the name. One idea that has returned to me time and again comes from Toynbee. He argued that barbarians rarely strike the final blow against civilisations. The “barbarians” who overran Rome in the early centuries of our era were not the destroyers of a mighty empire—they were merely scavengers, looting what had already begun to crumble from within.

“Civilisations don’t die of murder’ - writes Toynbee - ‘but of suicide’. They decay from within. But what is the nature of that decay?

II. Böckenförde Dilemma

In his eye-opening book Dominion, historian Tom Holland presents a striking argument: many of the so-called uncompromisable truths we hold today—such as the concept of human rights—are not eternal, self-evident principles but the product of revolutionary turmoils brought by Christianity. For the Romans, for instance, the idea that all humans possess inherent dignity would have seemed utterly absurd, as Holland captivatingly demonstrates.

But, what happens if we remove the very source that brought these ideas to life?

This is something was brought by the German constitutional lawyer Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde who wrote:

“The liberal secular state lives by prerequisites which it cannot guarantee itself.”

This means that, in the past, one could say, “All humans have rights because the Bible, God, or Christianity tells us so.” Today, we simply state, “All humans have rights,” but when asked why, we lack an authoritative answer. Instead, we offer something vague—“Because we are all human.”

This, according to Toynbee, is the moment when institutions begin to collapse. For a time, they may continue to function by inertia, sustained by the remnants of their former strength, but eventually, they falter and fall—taking civilisation down with them.

Toynbee described this in 1947, Böckenförde in 1976, Holland in 2019 but Dante saw this 700 years before them.

III. The Old Man of Crete

If in the previous canto Dante challenged his guide Virgil, in this canto Dante challenges another mentor of his - Ovid.

First was the Golden Age. Then rectitude

spontaneous in the heart prevailed, and faith.

Avengers were not seen, for laws unframed

were all unknown and needless. Punishment

and fear of penalties existed not.-

When Saturn had been banished into night

and all the world was ruled by Jove supreme,

the Silver Age, though not so good as gold

but still surpassing yellow brass, prevailed.(Ovid, Metamorposes Book I, 89-150)

Ovid’s description of how civilisation declined resembles almost with the exact precision to Dante’s description of the state of The Old Man of Crete.

Within the mountain is a huge Old Man,

who stands erect—his back turned toward Damietta—

and looks at Rome as if it were his mirror.The Old Man’s head is fashioned of fine gold,

the purest silver forms his arms and chest,

but he is made of brass down to the cleft;below that point he is of choicest iron

except for his right foot, made of baked clay;

and he rests more on this than on the left.

Ovid’s view of the human history was cyclical. Golden age decays and gives birth to chaos, chaos in its turn, in a series of metamorphosis creates the Golden age and so on. Dante’s view was different.

Each part of him, except the gold, is cracked;

and down that fissure there are tears that drip;

when gathered, they pierce through that cavern’s floorand, crossing rocks into this valley, form

the Acheron and Styx and Phlegethon;

and then they make their way down this tight channel,and at the point past which there’s no descent,

they form Cocytus; since you are to see

what that pool is, I’ll not describe it here.

As humanity’s harmony with God’s will disintegrates, fractures appear, and from these fissures, tears flow, giving rise to the rivers of the underworld—Acheron, Styx, and Phlegethon. Their very names reveal the fate of civilization in Dante’s vision: Acheron, derived from “pain”; Styx, from “hatred” and “sorrow”; and Phlegethon, from “blaze,” “burning,” and “violence.”

Even in the grim eras of Iron and Bronze, as portrayed by both Ovid and Dante, despite the suffering, violence, and hatred, some cohesion remains. Even when civilisation reaches its breaking point—like in Thomas Cole’s painting below—traces of its former order still endure.

These traces endure because they rest upon the fragile baked clay foot…

IV. The Breath of the Divine Order

In classical mythology, the first humans were formed from clay and brought to life by divine breath. The same holds true in the Biblical tradition, where Adam, too, is shaped from clay and animated by the breath of God.

The parallels between Canto XIII and Canto IV are striking. In both, Dante challenges the pagan poets he revers. He rejects the notion of fate—the idea that the future is determined.8 In the former, he denies that Polydorus was fated to be murdered; in the latter, he refutes Ovid’s belief in the cyclical nature of history. For Dante, civilisation does not decay by necessity but by choice. To paraphrase Nietzsche—whose words are often cut short—“God is dead. We have killed him.” Dante, however, would not see this murder as fate but as the consequence of human will. Civilisation is not doomed to self-destruction; it is built and undone by our own hands.

This is why Dante’s answer to the question “Can a civilisation survive if it loses its religion?” would be a resolute No. For him, as for Toynbee9 seven centuries later, religion is the foundation that sustains a civilisation’s moral and structural integrity. Without it, the framework begins to erode, and decline becomes inevitable.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

The Rain of Fire: Albertus Magnus, Aristotle and Alexander the Great

This striking visual image originates from a letter attributed to Alexander the Great, addressed to Aristotle, as quoted by Albertus Magnus. In it, the great conqueror describes a terrifying rain of fire descending upon his army in India.

Capaneus and Lack of Remorse

Even tormented by the fire rain, Capaneus remains unremorseful. There is not a single tear of regret. His defiance is his punishment, as he fuels his own suffering with pride and rage. Rather than breaking under divine justice, he becomes an eternal symbol of self-inflicted damnation.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

I hope you will forgive if my quote this time is going to be not from The Divine Comedy but from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. If, one day, I will feel confident enough, I will do a read-along of Metamorphoses too. It is also a divine gift to lovers of a beautiful verse. The excerpt below is what happens when ‘the baked clay’ foot breaks and everything collapses.

…Then the sailor spread his sails

to winds unknown, and keels that long had stood

on lofty mountains pierced uncharted waves.

Surveyors anxious marked with metes and bounds

the lands, created free as light and air:

nor need the rich ground furnish only crops,

and give due nourishment by right required,—

they penetrated to the bowels of earth

and dug up wealth, bad cause of all our ills,—

rich ores which long ago the earth had hid

and deep removed to gloomy Stygian caves:

and soon destructive iron and harmful gold

were brought to light; and War, which uses both,

came forth and shook with sanguinary grip

his clashing arms.

Characters:

- Alexander - Alexander the Great, whose letters to Aristotle detailing his campaigns and the wonders he saw there were popular into the middle ages, though now known to be of doubtful authenticity. In one account of his travels in India made popular through the writing of Albertus Magnus’ book on minerals, he recounts fiery flakes that rained from the sky.

- Cato - 95-46 BC. Cato the Younger was a Roman politician who studied Stoic philosophy, and who sided with Pompey against Caesar in the Civil War. After the battle of Pharsalia in which Caesar was the victor, Cato committed suicide to prove his commitment to his cause.

- Capaneus - One of the Seven against Thebes in Greek myth. When Dante calls him a giant, he is referring to “true giants or Titans, rebellious and defeated opponents of Zeus.”10

- Seven against Thebes - Seven kings of myth who attacked the city of Thebes in order to instate Polynices onto the throne. Brother to Eteocles and son of Oedipus, Polynices and Eteocles had been cursed to share their fathers throne, but Eteocles refused to surrender his portion. Polynices and the kings attacked Thebes and scaled the walls. Capaneus was one of the seven kings.

Sayers Hell 160

De meteoris I.iv.8

Genesis 19:24 KJV

Suddenly amid the stars was heard

The voice of Capaneus: 'Do no gods stand

For cowering Thebes? Where are the sluggard sons

Of this accursed country, Hercules

And Bacchus? Come yourself!—I am ashamed

To challenge lesser names—What worthier

Antagonist? The ashes and the tomb

Of Semele, behold are in my power.

Come, Jupiter, with all your fiery flames

Contest with me! Or is it braver to

Frighten a timid girl with thunderbolts

And raze the towers of your father-in-law?'

Statius, Thebaid 10.895-906

Sayers Hell 160

See the Old Testament book of Daniel 2:31-45

Singleton writes an extensive commentary on the architecture of the rivers of Hell in his Commentary on the Inferno 244-248.

There is a difference between ‘determination’ and ‘predetermination’. The latter is done by God, which Dante would believed to be so.

Toynbee’s view is nuanced and includes several factors for the civilisational decline and religious element explored here is foundational but not the only one. It is worth mentioning that Toynbee considers not only Christianity but also religions of other civilisations (21 in total). In other words, religion in every shape or form is foundational to a civilisation and its decline tears it apart.

Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes, 45 425n.

There was a definite catch in my throat when I read of Dante picking up the broken branches and placing them around the tree trunk of the suicide. A compassionate human gesture amongst all the pain and sorrow of these circles of the damned.

Vashik & Lisa, I was eagerly anticipating a Thomas Cole and you did not disappoint. Thank you - what a phenomenal essay.