Crushed by Gold, Consumed by Hate: Avarice and Wrath in Hell

(Inferno, Canto VII) The Circle of Avarice and the Circle of Wrath

“Our torments also may in length of time

Become our Elements.”

~ From Paradise Lost

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

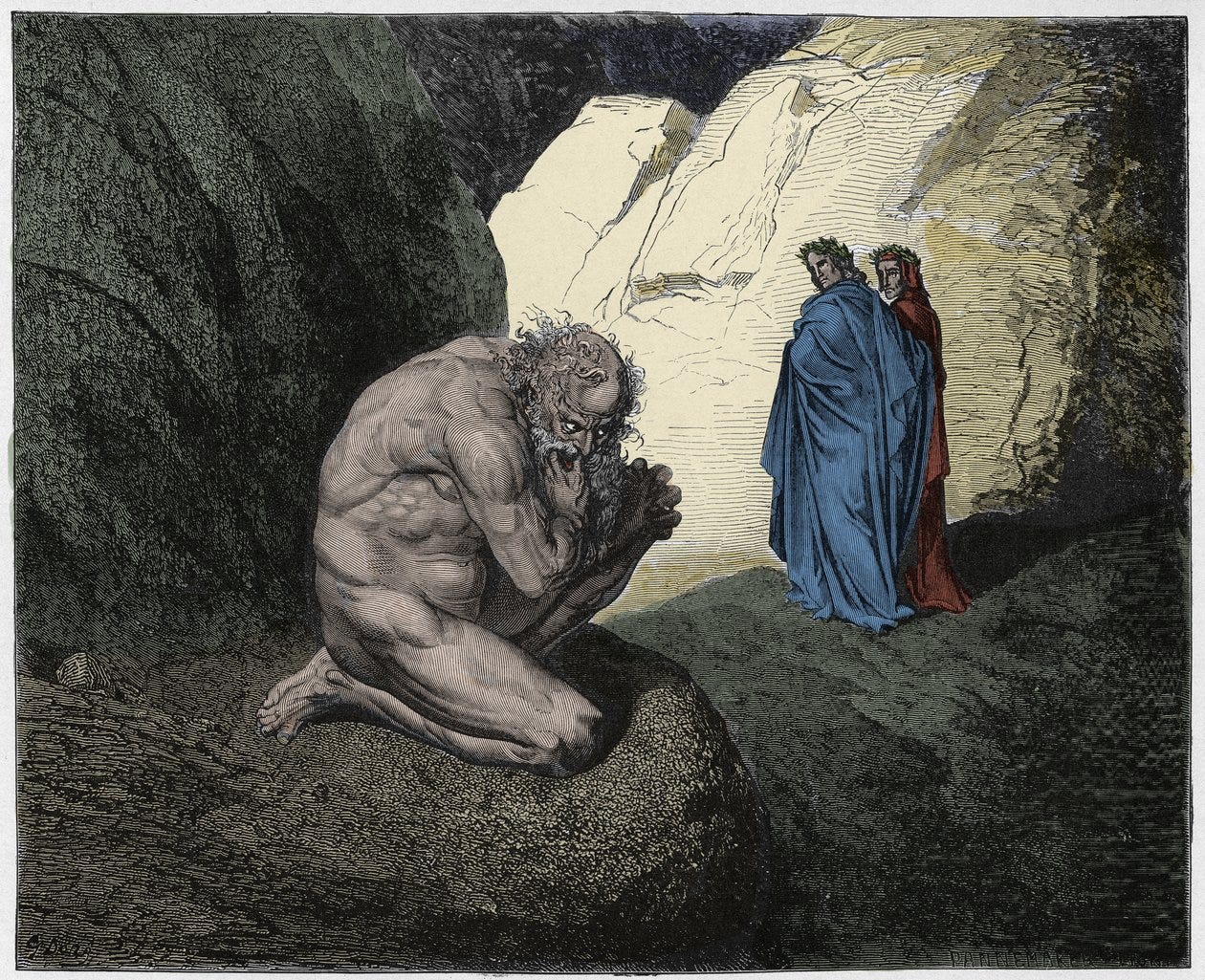

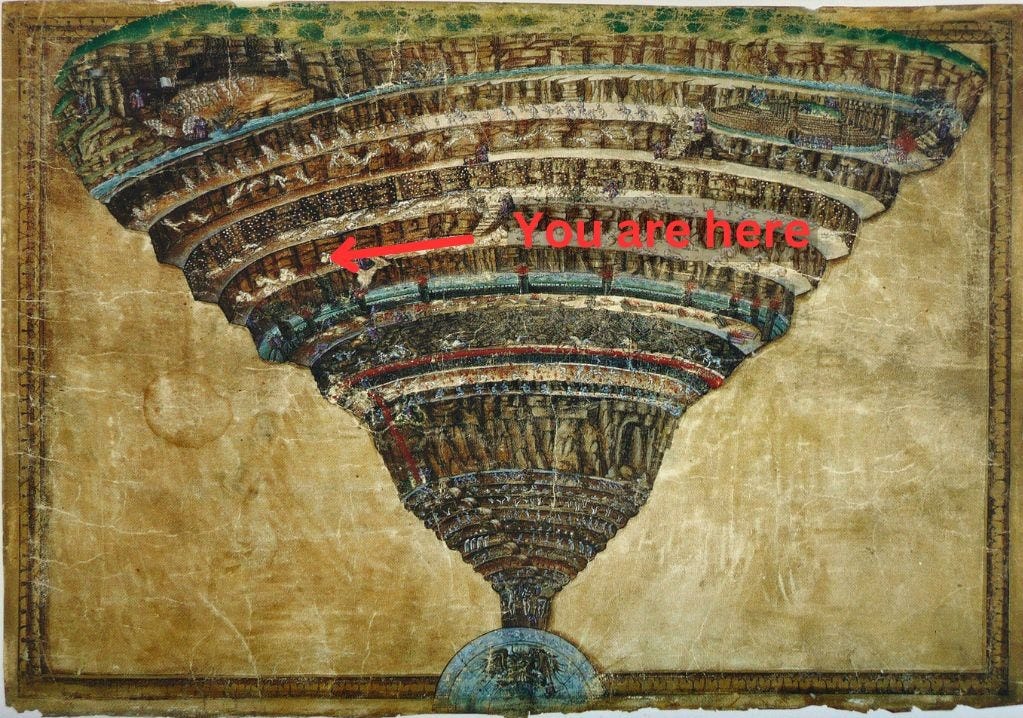

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this seventh Canto we find ourselves in Fourth Circle of the Avaricious. You can find the main page of the read-long right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character and symbolism explanations.

All wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Dante and Virgil descend into the Fourth Circle of Avarice - Plutus the guard, and Virgil’s rebuke - The Hoarders and the Squanderers crash together with weights on their chests - Virgil’s speech on Fortune - The Fifth Circle of the Wrathful - The swamp of the River Styx - The Wrathful, angry and sullen, wallow in the swamp

Canto VII: Summary

As Dante and Virgil descend into the Fourth Circle, their first encounter is with the guardian Plutus, who is crying out “Pape Satàn, pape Satàn aleppe!” (VII.1). While the scholarly consensus on the language generally considers it untranslatable, many of the theories of the meaning indicate other readings. Perhaps Plutus speaks a demonic language, a language like that of Babel,1 or the phrase may be Plutus expressing “in marvel, in succor, and in pain, for the aid of his superior.”2 Boccaccio also mentions it as a call for aid to his master in his Commento. Virgil may have even understood the language of Plutus, as he answers him with a rebuke.

This is the circle of Avarice - composed of the Miserly and the Spendthrift - and the two opposing sides of the extremes of relationship to wealth and possessions; from the outside we see the “restless acquisitiveness of misers and the ultimate worthlessness of all earthly possessions.”3 Between them, these shades either grasp or throw away, a disordered use of wealth.

The psychology of these levels of Incontinence evolve from Canto V with mutual indulgence of lust, to Canto VI with the selfish indulgence of greed, and finally the shift from indulgence to animosity and antagonism through the thwarting of desire.4

Virgil reassures Dante and rebukes Plutus, citing the high estate that has willed Dante’s journey, “where Michael took / revenge upon the arrogant rebellion” (VII.11-12).5

Plutus cannot stand against Virgil’s word of power:

As sails inflated by the wind collapse,

Entangled in a heap, when the mast cracks,

So that ferocious beast fell to the ground.

VII.13-15

They enter the Fourth Circle proper, and Dante is amazed at the collective suffering he continues to come across. The actions of the shades here are reminiscent of the movements of a mythical monster:

Even as waves that break above Charybdis,

Each shattering the other when they meet,

So must the spirits here dance their round dance.

VII.22-24

Charybdis was personified as a terrifying sea monster, and together with Scylla, represent two monstrous forces found mentioned in the literature of antiquity, including Homer, Ovid,6 and Apollonius of Rhodes in his Argonautica. The two monsters were seen as occupying both sides of the narrow Strait of Messina in the Mediterranean Sea, between the tip of Italy and Sicily, Scylla a ravenous monster and Charybdis a whirlpool that caught and sunk ships; in avoiding the dangers of Charybdis, ships would head straight for the rocky lair of Scylla. To be caught between Scylla and Charybdis then is to be between two almost impossible choices.

The howling sinners pushed weights with their chests, crashing into each other, accusing each other of the two spectrums of the relationships of wealth - hoarding and squandering. The heavy weights represent how heavily this burden weighed on them during life.

Dante asks Virgil to tell him who these groups are, and points to the tonsured shades, their shaved skulls indicative of membership in the church hierarchy. Virgil points to those indicated and tells Dante:

These to the left - their heads bereft of hair -

were clergymen, and popes and cardinals,

within whom avarice works its excess.

VII.46-48

Dante thinks he will recognize someone in this circle - perhaps he knew how fraught with these vices the city of Florence was - but Virgil considers them unrecognizable due to the layers of accumulated filth. He defines those who reside here: the Avaricious and the Prodigal; “Ill giving and ill keeping have robbed both / of the fair world and set them to this fracas” (VII.58-59).

Virgil uses this moment to point out the role of Fortune both in wealth and misfortune, and how fickle a mistress she is; no amount of goods or gold could satisfy such as are doomed to this circle. Dante asks to hear more, and Virgil gives an extended speech on the nature of Fortune from lines 70-99. This is the first of many speeches (by Virgil and others) that Dante uses to lay out his conception of “the plan of the physical and spiritual universe”7 and the order contained therein.

The workings of Fortune are out of the hands of humanity; Fortune in this capacity cannot be changed even by the use of reason, and is the great equalizer of all, as the “changes she brings are without respite” (VII.88). Here is Fortune described by a work contemporary with, though earlier than Dante, the French poem Roman de la Rose:

Fortune lodges discontent

within men’s hearts one hour, but to caress

and flatter them the next. No, not an hour

is passed without her change of countenance:

one minute she will smile, another frown.

She has a wheel she turns whene’er she will

but half a turn upsets those at the top

to grovel in the mud, while those below

are to the summit raised.8

Near the end of his speech on Fortune, Virgil describes the condition of the sufferers before them as one in which “all the gold that is or ever was / beneath the moon could never offer rest” (VIII.64-65). To the medieval mind, the realm below the moon was the sublunary realm, where all change took place, as opposed to the celestial realms in which all followed divine order.

The pilgrim and his guide cross over into the Fifth Circle, the last of the circles of Incontinence.

As we saw two manifestations of the use of wealth in the Fourth Circle, now we see two manifestations of the Wrathful: some are expressed externally, fighting and full of anger, others are sullen, submerged under the marshy Styx.

We had been sullen

in the sweet air that’s gladdened by the sun;

we bore the mist of sluggishness in us;

now we are bitter in the blackened mud

VII.121-124

Their inward gazing rage chokes them as they breathe in the thick swamp, unable to speak as their mouths are full of mire.

Dante distinguishes two kinds of Wrath. The one is active and ferocious; it vents itself in sheer lust for inflicting pain and destruction - on other people, on itself, on anything and everything it meets. The other is passive and sullen, the withdrawal into a black sulkiness which can find no joy in God or man or the universe9

Dante and Virgil circle the sufferers, watching and understanding, and come upon the foot of a tower.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

Here is the rule to remember in the future, when anything tempts you to be bitter: not, 'This is a misfortune' but 'To bear this worthily is good fortune.'

~ Marcus Aurelius

How many historical figures are admired today solely for their wealth? Very few or none at all. I searched my pantheon of admired figures—conquerors, philosophers, artists, sculptors, and travellers—yet not one among them is remembered for wealth alone. We honour those who embodied virtue, while those remembered for their vices serve not as objects of admiration, but as cautionary tales for the living.

In the Circle of Avarice, for the first time since encountering the neutrals in the Ante-Inferno, we do not meet any sinners whose identities are known to us. The nature of the spendthrifts and hoarders mirrors that of the neutrals; like them, they neither contribute, cultivate, nor nurture anything in life. What they possess is squandered or hoarded in vain, leaving nothing of lasting value.

And he to me: “That thought of yours is empty:

the undiscerning life that made them filthy

now renders them unrecognizable.

Their Sisyphean punishment is among the most visually striking torments in The Divine Comedy—endlessly pushing heavy weights with their chests, only to collide and reverse direction, trapped in a futile cycle of excess and waste.

Ill giving and ill keeping have robbed both

of the fair world and set them to this fracas—

what that is like, my words need not embellish.

I. The Choice Between Charybdis and Scylla

Avaricious merchants were held responsible for the decline of Greece’s Golden Age.

Even as waves that break above Charybdis,

each shattering the other when they meet,

so must the spirits here dance their round dance.

In Greek mythology, Charybdis was a monstrous sea creature that dwelled in the Strait of Messina, creating deadly whirlpools by sucking in vast amounts of water. Directly across from her lair resided Scylla, a many-headed monster that preyed on passing sailors. When Odysseus was forced to choose between the two perils, he opted to sail closer to Scylla, sacrificing a few men rather than risking complete destruction in Charybdis’ all-consuming whirlpool.

Charybdis is cursed to eternally swallow and regurgitate the sea, never satisfied, never creating—only taking and consuming. This mirrors the hoarder (avaricious merchant), who accumulates wealth endlessly but never shares or contributes to the common good.

II. Faceless and Nameless Merchants

If gluttony is a vice of the flesh, avarice is a vice of the mind. In Plutus, Greek mythology’s personification of wealth, those two vices meet together. He is like a faceless merchant, muttering unintelligible words and invoking Satan as he beholds the living Dante descending into his circle of Hell.

Virgil’s words are telling of how vices of the mind make us rot from inside:

Then he turned back to Plutus’ swollen face

and said to him: “Be quiet, cursed wolf!

Let your vindictiveness feed on yourself.

Our sins, whether avarice or wrath, consume us from within. Virgil tells us that those sinners who are eternally busy with the Sisyphean task bark when they struck each ‘at that point’. They are ‘filthy’ and their ‘undiscerning life’ deems them unrecognisable.

III. Fortune does not favour anyone

In the Second Canto, Beatrice tells Virgil that Dante’s journey is not dictated by Fortune, but granted by divine will and his own resolve. When Dante asks Virgil to tell more about the nature of Fortune, Virgil says:

And he to me: “O unenlightened creatures,

how deep—the ignorance that hampers you!

I want you to digest my word on this.-

E quelli a me: «Oh creature sciocche,

quanta ignoranza è quella che v’offende!

Or vo’ che tu mia sentenza ne ’mbocche.

‘mbocche (from imboccare) can also mean “to spoon-feed.” Essentially, Virgil is telling Dante, “Let me spoon-feed you wisdom,” urging him to absorb and digest his words. And here we hear the words of Boethius once again. Lady Fortune is blindfolded and her role is (pay attention to Mandelbaum’s interpretation) ‘to shift, from time to time, those empty goods’.

This reminds me of a Stoic idea that there are three types of phenomena in our lives: good, bad, and indifferent. Wealth is an “empty good,” an indifferent possession, for, as Virgil tells us, it is governed by Fortune, who endlessly redistributes it, passing it from nation to nation, person to person. Those condemned to push boulders with their chests—both the spendthrifts and the hoarders—rebelled against this natural order. The hoarders clung to their wealth out of fear of losing it, while the spendthrifts squandered it recklessly, failing to recognise its fleeting nature.

But she is blessed and does not hear these things;

for with the other primal beings, happy,

she turns her sphere and glories in her bliss.

And once again, it was the Stoics and Boethius who taught us that we should welcome both good and bad Fortune, for the mind is its own domain—it can make a heaven out of misfortune and a hell out of prosperity.

All fortune is good fortune; for it either rewards, disciplines, amends, or punishes, and so is either useful or just.

IV. Sadness is another form of anger

We find the sullen and wrathful submerged in the infamous River Styx. The river’s name itself originates from Greek, deriving from words meaning sorrow (stygos) and hatred (stygein), reflecting the torment of those condemned within its waters.

For Dante, sullenness and anger stem from the same source—hate. The difference lies in their direction: sullenness turns inward, festering in silence, while anger erupts outward, lashing at the world.

There is a curious Russian proverb, commonly spoken yet difficult to translate precisely. Word for word, it reads: “Those who are filled with resentment and offense carry heavy water.” It evokes the idea that harbouring grudges is a burdensome weight, much like carrying an unseen but exhausting load.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Themes 🖼️ :

Sluggishness

There are words that the sullen utter while submerged in slime: ‘we bore the mist of sluggishness in us’. We recall how Dante found himself lost in a shadowed forest, having strayed from the right path because he was “full of sleep.” Just as he wandered in darkness, internal anger, sullenness, and sin plunge the soul into a state of spiritual slumber, dulling one’s awareness and leading to moral blindness.

Fortune does not submit to your control

The idea that one cannot rebel against Lady Fortune is clear—her wheel turns endlessly, lifting some up while casting others down. If you find yourself at the bottom, remember that her wheel will rise again. When fortune no longer favors you, see it not as misfortune, but as a test—a chance to strengthen your resolve and discipline your spirit.

Opposites of the same sin

Two extremes of the same sin: Avarice—manifesting as both hoarding and reckless spending—and Anger—expressed through both wrathful outbursts and silent, brooding resentment.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

Wedged in the slime, they say: ‘We had been sullen

in the sweet air that’s gladdened by the sun;

we bore the mist of sluggishness in us:now we are bitter in the blackened mud.’

This hymn they have to gurgle in their gullets,

because they cannot speak it in full words.”

Characters:

- Plutus - The god of wealth in Greek antiquity, he is the guardian of the Fourth Circle.

- Charybdis - The legendary sea monster of antiquity, described thus in Homer’s Odyssey:

On one side

was Scylla, and on the other side was shining Charybdis,

who made her terrible ebb and flow of the sea’s water.

When she vomited it up, like a cauldron over a strong fire,

the whole sea would boil up in turbulence, and the foam flying

spattered the pinnacles of the rocks in either direction;

but when in turn again she sucked down the sea’s salt water,

the turbulence showed all the inner sea, and the rock around it

groaned terribly, and the ground showed at the sea’s bottom,

black with sand; and green fear seized upon my companions.

We in fear of destruction kept our eyes on Charybdis,

but meanwhile Scylla out of the hollow vessel snatched six

of my companions, the best of them for strength and hands’ work…

Odyssey XII.234-246

- Fortune - Fortune and her Wheel were no respecters of persons, status, or wealth; in the medieval mind, Fortune could change as quickly as the blowing sands, and was a fickle friend.

- Styx - One of the five rivers of the Underworld, the word itself means “hateful.”

We will see another untranslatable phrase in Inferno XXXI.67 with Nimrod.

Singleton Commentary on Inferno, VII.1, pg. 109

Mandelbaum VII.28n

Sayers Hell 114

From Revelations 12:7-9: 7 And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, 8 And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven. 9 And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.

Ovid Metamorphoses VII.99-102: “And what of ship-devouring Charybdis, / that sucks the sea in and then spits it out? / What of rapacious Scylla, surrounded by her savage dogs, baying off Sicily?” Medea speaks to Jason (of the Golden Fleece) to show him that she is not afraid to betray her father and leave Colchis with Jason.

Sayers Hell 115

Guillaume de Lorris & Jean de Meung, Roman de la Rose 3923-3931

Sayers Hell 114

Hello everyone,

The chat thread for this Canto is now open for discussion:

https://open.substack.com/chat/posts/cd392a1b-8fa3-41e8-a237-6af03a9e8bbf

You can find all discussion threads here :)

https://armenikus.substack.com/publish/post/154549135

"Their inward gazing rage chokes them as they breathe in the thick swamp, unable to speak as their mouths are full of mire." Such a pitch perfect description of the toll of bitterness and long held grudges. Thank you as always for your insights into each Canto.