Dante and Victor Hugo: The Turning of the Will and the Moment Life Changes Forever

(Purgatorio, Canto V): Three souls, one moment, and the mystery of mercy

Certain thoughts are prayers. There are moments when, whatever be the attitude of the body, the soul is on its knees.

~ Victor Hugo

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Fifth Canto of the Purgatorio, we encounter those who died a violent death. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

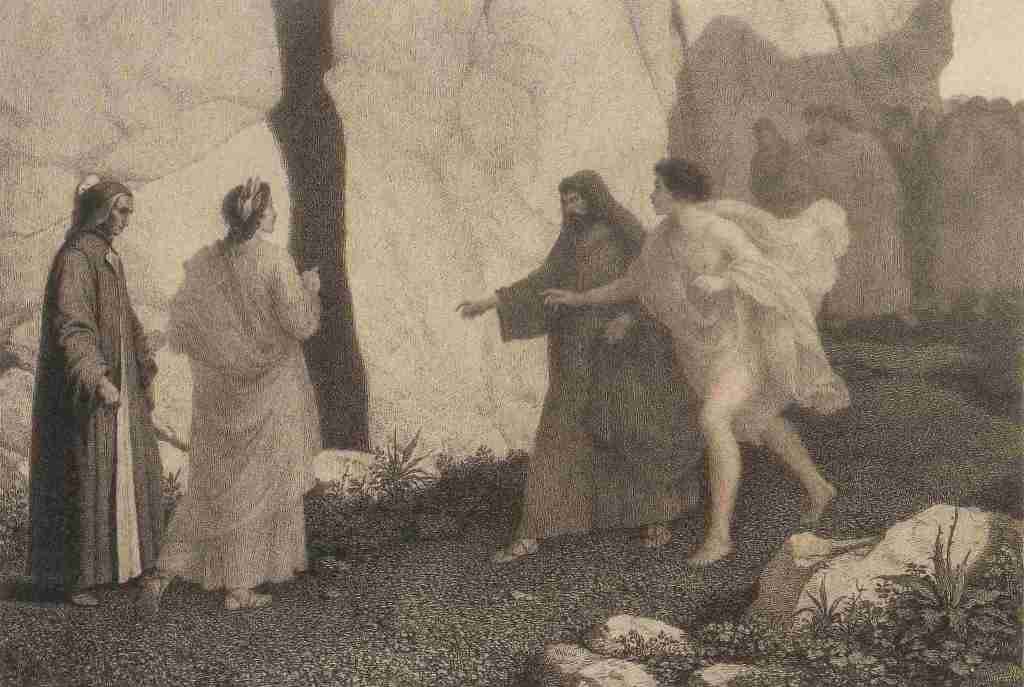

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

The second terrace of Purgatory - Souls are amazed at Dante’s shadow - Virgil’s admonition to continue moving - The Unshriven who died a violent and sudden death - The stories of Jacopo del Cassero, Guido da Montefeltro and La Pia.

Canto V Summary:

Dante had already started to follow Virgil away from Belacqua and the Indolent shades, when those he left behind called out, exclaiming over the shadow that he cast. Their amazement gave Dante pause, and he turned to look at their astonishment.

Some commentators have pointed to this moment of Dante’s attention to the amazement of the souls as falling into pride; Benvenuto, the fourteenth century commentator, refutes this idea, saying instead that Dante felt joy in having been chosen for the task of the pilgrimage and in being recognized by those souls.

Virgil quickly stepped in, pointing Dante back to recovering his single minded purpose:

“Why have you let your mind get so entwined,”

my master said, “that you have slowed your walk?”

Why should you care about what’s whispered here?

Come, follow me, and let these people talk:

stand like a sturdy tower that does not shake

its summit though the winds may blast; always

the man in whom thought thrusts ahead of thought

allows the goal he’s set to move far off-

the force of one thought saps the other’s force.”

V.10-18

One theme that we will continually encounter as we move through Purgatory is the imperative of continual movement; as we saw with the Indolent, the lack of movement only leads to stagnation and dissipation.

No man, having put his hand to the plough, and looking back, is fit for the kingdom of God. Luke 9:62

The image of the sturdy edifice, or the unbreakable resolve, is one that Dante found in the Aeneid:

He’s like a crag as it stands unmoved against battering high seas,

He’s like a crag in the high seas, as breakers crash down upon it,

Self-maintained by its own sheer mass while, relentlessly, rollers

Bark all around, and around it the rocks and the reefs rumble endless protests.

Aeneid vii.586-590

Dante could only submit, blushing, and focus his attention as Virgil guided.

Here we encounter the next group of souls singing the Miserere, one of seven penitential Psalms, or Psalms of repentance, in that now familiar Purgatorial harmony:

Have mercy upon me, O God, according to thy lovingkindness: according unto the multitude of thy tender mercies blot out my transgressions. Wash me thoroughly from mine iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin. For I acknowledge my transgressions: and my sin is ever before me.

Psalm 51:1-3

Miserere di me happens to be the first words that Dante spoke to Virgil before recognizing him, what now seems long ago in Inferno canto I. Note the difference in Dante’s fear in his expression of the words in the beginning, and that of our penitent souls, who are calling out with the knowledge that their desire will be fulfilled:

When I saw him in that vast wilderness,

“have pity on me,” were the words I cried,

“whatever you may be - a shade, a man.”

Inferno i.64-66

As these souls are still seeking entrance into Purgatory proper, this prayer is fitting. They could not do penance in life, as they died suddenly; this is the group of the Late-Repentant who died by violence - the Unshriven, or unpardoned.

For a second time, the notice of Dante’s living form causes amazement in these souls as their song shifts from the singing of the Psalm to a drawn out sound of wonder. Two unnamed messengers are dispatched to inquire about him, and they rush forward to ask “Please tell us something more of what you are.” (30).

Virgil says that having seen his shadow should be enough of an explanation, but that if they make Dante welcome, it would be to their advantage in gaining prayers above once he has returned.

These souls move with a quickness that is in direct contrast to the slow lethargy of Belacqua and the Indolent:

Never did I see kindled vapors rend

clear skies at nightfall or the setting sun

cleave August clouds with a rapidity

that matched the time it took those two to speed

above; and, there arrived, they with the others

wheeled back, like ranks that run without a rein.

v.37-42

The medieval scientific mind saw these ‘kindled vapors’ as the cause of meteors or summer lightning. As the group moved quickly toward Dante, Virgil encouraged him to listen, but to keep moving as he listened; again, this theme of movement forward.

As one, the group cried out to him in their request, noticing that Dante did not stop for them:

“O soul who make your way to gladness with

the limbs you had at birth, do stay your steps

awhile,” they clamored as they came, “to see

if there is any of us whom you knew,

that you may carry word of him beyond.

Why do you hurry on? Why don’t you stop?”

v.46-51

The souls then explain who they are, with the distinction of their violent deaths, and that, as is stated in the Lord’s Prayer, they both repented of their own sins and pardoned others who had sinned against them, leaving them at peace:

And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.

Matthew 6:12

We all were done to death by violence,

and we all sinned until our final hour;

then light from Heaven granted understanding,

so that, repenting and forgiving, we

came forth from life at peace with God, and He

instilled in us the longing to see Him.”

v.52-57

Even while Dante does not recognize any of them, still he is willing to grant them favor in the name of the highest peace of God that he is aiming toward.

Here, the first of three souls with whom he will speak comes forward, and while not introducing himself, commentators have named him as Jacopo del Cassero. Jacopo was a Guelf leader who begged that Dante be a messenger for him if he ever found himself between the lands of Romagna and Naples - those ruled by Charles of Anjou - in a place called Fano, Jacopo’s homeland. If Dante could speak of him, then the people there could pray for him to aid in his purging of heavy sin. The souls in Ante Purgatory, are not yet at that stage, as they are waiting for the opportunity to do so. They first must travel to the gate.

He died in Antenori’s lands, near Padua. Recall the second ring of the ninth circle of Hell was named after Antenor, traitors to their country.

The name thus makes a pointed allusion to the treacherous complicity of the Paduans in the murder of Jacopo.1

He was killed by the workers of Azzo of Este, who ambushed him outside of the town of Oriaco; in his flight, he fell into a swampy marsh, and watched his lifeblood spill out of him. This moment, as his soul left his body in that spill of blood, was the moment of repentance; note that if he had to be both “repenting and forgiving” (55), this means he also had to be forgiving of his murderers. But why did they hate him so? Aside from the political reasons of Jacopo being made podesta, a high government official in Bologna, when Azzo desired the post, Jacopo created animosity toward Azzo with his words:

He was not satisfied with doing things to hurt the friends of the marquis, but he would continually indulge in vulgar vilification of him, saying he had slept with his stepmother, that he was the son of a washerwoman, that he was evil and cowardly. His tongue never tired of abusing him. These words and deeds caused such great hatred in the marquis, that he had him killed in this way.2

The next soul to step forward opens with an adjuration, a “mutual wish formula,” a blessing for a blessing:

Another shade then said: “Ah, so may that

desire which draws you up the lofty mountain

be granted, with kind pity help my longing!”

v.85-87

The soul identifies himself as Buonconte from Montefeltro, a name we have encountered before; Dante tells us of his father, Guido, a Ghibelline leader, in the Inferno.3 Buonconte laments that there is no one on earth to pray for his soul, not even his wife Giovanna or his family. He also is asking for intercession for prayer, but from a place of sadness, that there is no one to offer it for him.

It is undoubtedly the case that any number of people who read or heard the poem in the fourteenth century actually prayed for the souls of those whom Dante reports as needing such prayer.4

Dante knows of him; in fact, Dante fought in the very battle in which Buonconte, on the losing Ghibelline side, perished. For Dante, that battle of Campaldino was a victory for the Florentine Guelphs. He also knows that Buonconte’s body was never found, and asks what happened that that would be so. Dante’s account is conjecture, but fitting for the circumstances.

Buonconte tells Dante of his injury, of running, fleeing across the plain with his dying breath calling out to the Virgin Mary - his moment of repentance - at the place that the stream Archiano joined with the river Arno.

In the Comedy, the deaths of the two lords of Montefeltro form, as it were, companion-pieces: the father being damned and the son saved at the last moment, the one by a false and the other by a true act of contrition.5

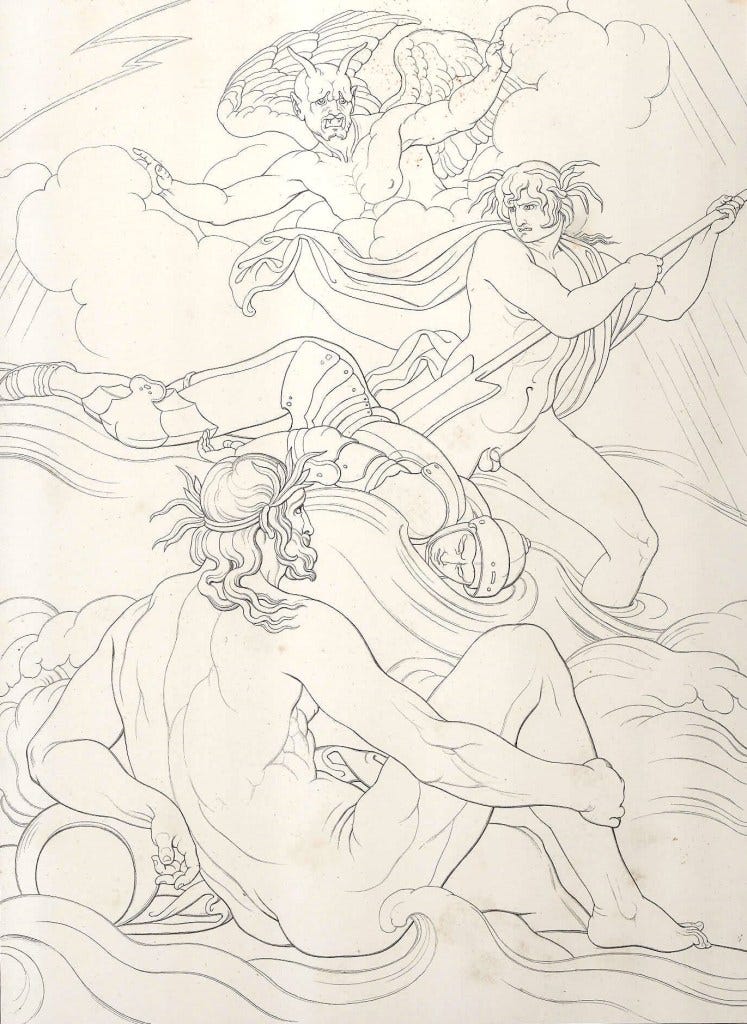

He wants the next fantastic image of what happened to his body to be remembered by men above; as God’s angel came to retrieve his soul, a devil called out angrily that he had lost what he expected in that moment of repentance;

I was taken by God’s angel,

but he from Hell cried: ‘You from Heaven - why

do you deny me him? For just one tear

you carry off his deathless part; but I

shall treat his other part in other wise.’

v.104-108

Buonconte’s father had a similar experience as he recounted to Dante in the Inferno, as a devil and St. Francis fought over his soul:

Then Francis came, as soon as I was dead,

for me; but one of the black cherubim

told him: ‘Don’t bear him off; do not cheat me.

He must come down among my menials;

the counsel that he gave was fraudulent;

since then I’ve kept close track, to snatch his scalp;

one can’t absolve a man who’s not repented,

and no one can repent and will at once;

the law of contradiction won’t allow it.’

Inferno xxvii.112-120

For we must believe that when the soul leaves the body, the good and the evil spirits stand by, one or more, and then a true sentence is passed; if the soul is judged to be good, he is led away to Heaven in the company of a good angel, or else to Purgatory, from which, after he has been cleansed, he will be led out by the same escort…if however, the soul is judged to be evil, he will be led by the devil into Hell.6

The devil, angered at the angel getting Buonconte’s soul, took out that anger on the body of Buonconte.

His evil will, which only seeks out evil,

conjoined with intellect; and with the power

his nature grants, he stirred up wind and vapor.

v.112-114

The nature of devils and angels, it was believed, had power over the elements; this devil drew up a storm and created a pouring rain which flooded the Arno river, sweeping the body of Buonconte away with it, where he was washed along like so much detritus, to become one with the jumble of debris as found in flooded rivers. So was he lost. Even the cross he had formed on his body with his arms, like a final blessing, was undone.

Finally, the third soul that Dante encountered gave her plea; brief, but full of meaning and emotion. She entreated Dante that, after he returned to the world of the living, that he remember her. Her name is La Pia, or Piety, and with the briefest of speeches, expresses much:

“May you remember me, who am La Pia;

Siena made - Maremma unmade - me:

he who, when we were wed, gave me his pledge

and then, as nuptial ring, his gem, knows that.”

V.133-136

This cryptic ending is the story of Pia dei Tolomei, from Siena, who, according to the early commentators, was murdered by her husband, the Guelf leader Nello dei Pannocchieschi at his castle in Maremma. It is said that he had her cast from a window so that he could marry a wealthy heiress, but this has been widely disputed in later evaluations. Her sweet response lacks in blame or judgment of her fate, only a wish for the blessing of prayer.

💭 Philosophical Exercises

"It is nothing to die; it is frightful not to live."

~ Victor Hugo

We never know how much hunger for bread can change our attitude to life.

In the case of one of the most famous characters in world literature, hunger did not only steal 19 years of his life by placing him in prison—it did something far worse: it stole his soul and redirected his will from good toward evil.

Prison rarely redirects one’s will from evil to good; more often, it merely sedates the appetite for it. Such was the case for our character. Though released from the physical walls of his cell, he found himself locked in a different kind of cage — the cage of social rejection. He walked into the most expensive hotel, money in hand, and asked for a room. But the receptionist, having recognised him as a former prisoner, told him to leave, despite his ability to pay.

Hatred and resentment toward everyone—our former prisoner rejected society just as it had rejected him. He wasn’t even allowed to rest his head on a bench in the town square.

It was only by chance that he came to the door of Bishop Myriel, who welcomed him into his home, fed him, gave him fresh clothes, and told this outcast that since the house had no spare bed, he—the bishop, the master of the house—would sleep on the sofa that night, so his guest, spurned by every soul in town, could sleep peacefully in the bed of one of God’s greatest servants in France.

And how did the outcast repay the Bishop’s kindness?

In the middle of the night, he stole the silver from Bishop Myriel and fled. The housekeeper, horrified by the betrayal, called the police. The thief was quickly caught and brought back to the Bishop so charges could be pressed.

But Bishop Myriel?

The old man looked at the officers and said that the silver had been a gift. He not only refused to accuse the thief but reminded him that he had forgotten the candlesticks—the most valuable pieces. And so, the thief walked free.

My reader might have already guessed the name of the thief, of this outcast. Yes, you are correct it is Jean Valjean, the main protagonist of Victor Hugo’s masterpiece - Les Misérables.

The English translation of Les Mis (for the sake of brevity) spans about 1,200 pages in the wonderful Christine Donoghuer’s translation. I was so engrossed in the story that I finished the book within a week and was blown away by how this book changed me spiritually. Little I knew, Victor Hugo was profoundly influenced by Dante and the Divine Comedy…

I. “Turning of the Will”

Once you know that Hugo was influenced by Dante, many things will make sense in his masterpiece. Do you remember, my reader, what happens to Jean Valjean after he is released by the police?

As Jean Valjean walks away from Bishop Myriel’s house, his heart still hardened and filled with contempt, he mocks the old priest’s naïveté for letting him go so easily—with his silver. On the road, he encounters a poor boy who accidentally drops a coin—the only money the child possesses. Without hesitation, Valjean snatches it. The boy flees, crying. And then, something happens. Valjean sees himself. He sees the ugliness he has become, and he is suddenly revolted by his own reflection.

Bishop Myriel’s divine grace had opened a crack in Valjean’s heart, a heart long sealed by years of injustice and suffering. It is in that moment that a sliver of light breaks through.

In the works of Aquinas and Augustine, this is called the turning of the will. Some might call it an awakening. But I believe that a mere realisation of how low one has fallen is not enough. Just look at Belacqua, whom we met in the previous canto—he is fully aware of the mountain he must climb to be transformed, and yet he chooses to sit, joke, and wait.

This ‘turning of the will’ happens when one’s spirit, essence, and consciousness turns away from the old ways and actively re-directs those actions towards virtue.

II.

In contrast to the saved souls we meet in this canto, Jean Valjean did not die, he continued to live. But his turning of the will allowed him to become a beacon for others, helping many of the wretched to survive the injustices they faced.

For the first time in our journey, we witness the key difference between the realm of Inferno and that of Purgatorio: all three saved souls here could easily blame someone else for their fate. This is precisely what the damned in Inferno kept doing—they blamed everyone and everything but themselves. Here, however, the souls do not blame, do not resent, as Jean Valjean once did before that pivotal moment. Instead, they ask for prayers from the living.

The key element in the turning of the will is the moment one takes responsibility for one’s own soul. The damned of the Inferno never reached this point—they perpetually shifted blame outward. But in truth, each soul possesses the freedom either to destroy itself or to grow.

One must nourish one’s own garden. We are all given the tools, we must choose whether to ruin the soil or make it bloom.

III.

His evil will, which only seeks out evil,

conjoined with intellect7; and with the power

his nature grants, he stirred up wind and vapor.(Lines 112-114, Mandelbaum)

The parallels between Jean Valjean’s path and that of the saved souls in this canto are striking—particularly in the way Hugo so beautifully personifies Dante’s vision of undeserved divine grace through Bishop Myriel. My retelling hardly does justice to the sublime writing of Hugo, who shows us that Myriel had every reason not to open his home to Valjean, yet still does. He has no reason to offer Valjean a place to sleep, yet offers him his own bed. And finally, of course, Myriel has every reason to punish Valjean for his betrayal, but instead gives him more.

The souls of Cassero, Montefeltro and La Pia led, most likely8, led lives similar to that of Jean Valjean before his ‘turning’. Yet their repentance, the turning of the will, even in the final moments of life, that last glance in the mirror and recognition of their own ugliness, was enough to merit the unearned gift of divine grace.

More on Hugo’s relation to Dante in this post ⭕️

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. Stand like a sturdy tower

“Why have you let your mind get so entwined,”

my master said, “that you have slowed your walk?

Why should you care about what’s whispered here?Come, follow me, and let these people talk:

stand like a sturdy tower that does not shake

its summit though the winds may blast; always

Perhaps some of the most beautiful and inspiring lines from Virgil appear in this canto—a reminder that there will always be those who seek to hinder our progress. We cannot escape them, but we must never lose sight of our path.

II. ‘Spiriti ben nati’ vs ‘mal nati’

In this canto we also see how the nature of the spirits change, they are here referred to ‘spirit ben nati’ (spirits born for bliss), in contrast to mal (evil).

III. Is Virgil making a mistake again?

Virgil rebukes Dante for being distracted by the ‘whispers’ of the first group, yet when they encounter the next group (the ones we discussed above) Virgil remains silent.

Why so?

Perhaps because Dante’s interest in the first group of souls was driven not by a desire for moral instruction, but by mere curiosity: they were astonished to see a living man in Purgatory, and he was captivated by their reaction.

The next group, however, those who sing the Miserere have something to teach him. Their presence offers guidance, not distraction.

IV. The importance of forgiveness

The souls who wish to enter Purgatory must not only repent but also forgive their wrongdoers. This is a part of taking responsibility for one’s journey; the moment we blame others for our misfortune, we place responsibility in their hands, the fate of our lives and our souls to them.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

His evil will, which only seeks out evil,

conjoined with intellect; and with the power

his nature grants, he stirred up wind and vapor.

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on Purgatorio 99

Singleton, quoting the commentator Lana, 100.

Inferno xxvii.19-132

Jean & Robert Hollander, Purgatorio 110

Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory 108

Bonaventure, Commentary on the Sentences of Lombard, IV XX, i, a. I, q. 5, response.

Interesting that ‘will’ in itself is neither good or bad, it is how you choose to use it or direct it.

La Pia’s life is not well know or documented, we are not certain what precisely led to her murder, and yet it is very likely that she did not lead a noble and virtuous life, but recognised and repented at the last moment.

Another brilliant post, Vashik, like every week, full of intriguing details and useful background information. I am also much impressed by you having read Les Misérables within a week - that is quite an achievement! Hat tip to you for this.

Thank you for your marvelous commentary and notes!