Fate, Free Will and Despair: What Helps Us Endure?

(Inferno, Canto XIII): The forest of those violent against themselves, Aeneas, Polydorous

Civilisations die from suicide, not by murder.

~ Arnold J. Toynbee

❗️ A small note that this canto touches upon the topic of suicide.

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Thirteenth Canto we enter the dark wood of Violence against Self. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Dante and Virgil enter the second ring of the Seventh Circle - Violence against Self and Possessions - A dense dark wood - Harpies perched in blackened twisted trees - The snapped twigs bleed - Suicides are entombed in the trees - Pier della Vigna - The Profligates chased by dogs - Lano of Siena and Jacopo da Santo Andrea

Canto XIII: Summary

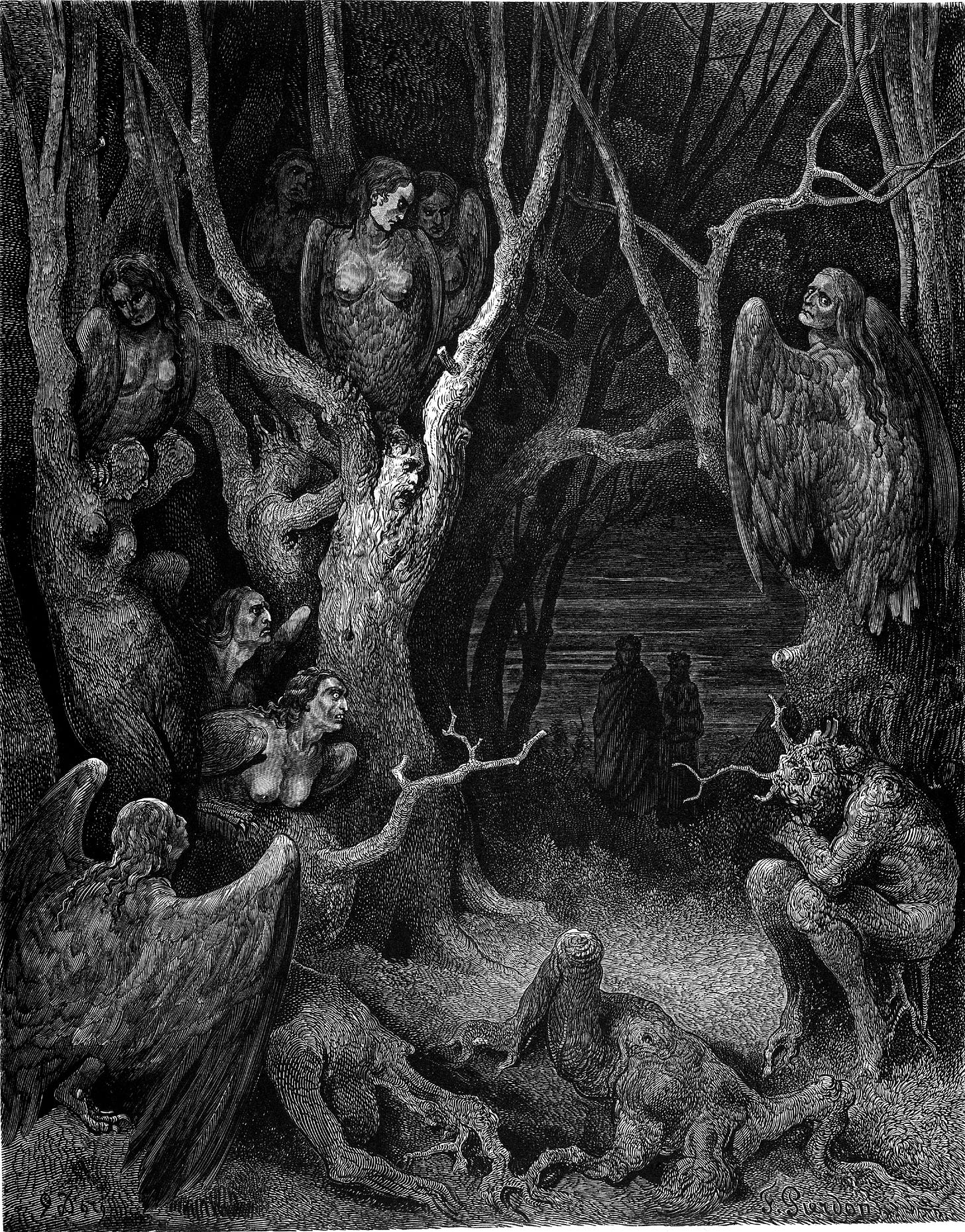

Nessus the Centaur has left Dante and Virgil behind at the river Phlegethon, and the Poet and the Pilgrim find they have entered a dense and pathless wood, an inhospitable forest of gnarled and blackened shrubs and thorns. Such a dense and disordered wood inspired fear in the medieval mind. This is the second ring of the Seventh Circle: Violence against Self. Here nest the Harpies:

This is the nesting place of the foul Harpies,

who chased the Trojans from the Strophades

with sad foretelling of their future trials.

XIII.10-12

The Harpies are monstrous birds with the heads of women, another part beast and part human creature embodying a “will to destruction”1 In Virgil’s Aeneid, the Harpies attacked Aeneas and his men feasting on the shores of the Strophades islands. Aeneas recounts the story to the Queen Dido:

No grimmer monster than these, worse plague, or divine show of anger

ever protruded its fiendish head from Stygian waters:

Harpies can fly; they have faces like girls’, and discharge from the bellies

foulest filth. They have hands like claws, they have cheeks ever pallid, hungering mouths.

Aeneid III.214-218

Virgil helps Dante to understand this new realm they have entered; what Dante is about to see is so fantastic that in order to understand it he must uncover for himself. If Virgil even attempted to explain, Dante would not believe it.

He was surrounded by cries from the wood that did not seem to come from any being that he could see; and was sure that Virgil thought Dante believed there must be someone hiding. Virgil asks him to break a twig off of a nearby plant; thus will his thoughts of confusion be broken off as well.

Dante complies and hears a voice, hurt by what he has done, and more, the plant itself is bleeding.

As from a sapling log that catches fire

along one of its ends, while at the other

it drips and hisses with escaping vapor,

so from that broken stump issued together

both words and blood; at which I let the branch

fall, and I stood like one who is afraid.

XIII.40-45

Virgil apologizes to the soul within the broken off twig for the pain caused, but it was the only way to bring understanding; if Dante could have believed the tale when reading it in Virgil, he would not have needed such an example.2 Virgil asks him to explain who he is, so that Dante can bring him back to notice in the mortal world.

The soul that was trapped within the trunk spoke, and gave veiled references to who he was;

The one who guarded both the keys

of Frederick’s heart and turned them, locking and

unlocking them with such dexterity

that none but I could share his confidence

XIII.58-61

Here is Pier delle Vigna, minister to Emperor Frederick II, who is explored in more detail below. The shade said he was faithful to his position, but that the whore - envy - lived in Caesar’s dwelling - the Emperor’s court - and thus he was defamed and accused of crimes against the Emperor.

He thought he could “flee disdain through death” but that made him “unjust against” his own self, through suicide (XIII.71-72). The moral element of suicide, in its placement at this level, is as a violent sin of malice, in doing purposeful harm.

Vigna asks Dante to remember him and his innocence to the world above:

If one of you returns into the world,

then let him help my memory, which still

lies prone beneath the battering of envy.

XIII.76-78

Virgil encourages Dante to ask questions; but Dante is so overcome by piety that he would rather Virgil speak, so Virgil asks the soul to explain how they are bound into the shrubs and plants around them, and if they will ever be freed from them.

They are sent to that realm by Minos the judge, he replies, where the soul falls like a seed to the ground of the wood, there to sprout into the plant that will encase their soul.

It rises as a sapling, a wild plant;

and then the Harpies, feeding on its leaves,

cause pain and for that pain provide a vent.

XIII.100-102

That “vent” is an outlet for the pain; “the trees can only utter when broken and bleeding. The Harpies, by tearing the leaves, make wounds from which issue the wails that puzzled Dante.”3

Vigna tells them that even after attending the Last Judgement, when the dead are to rise and regain their bodies, the suicides, having already thrown away their bodies, will be denied them; a form of contrapasso.

Like other souls, we shall seek out the flesh

that we have left, but none of us shall wear it;

it is not right for any man to havewhat he himself has cast aside. We’ll drag

our bodies here; they’ll hang in this sad wood,

each on the stump of its vindictive shade

XIII.103-108

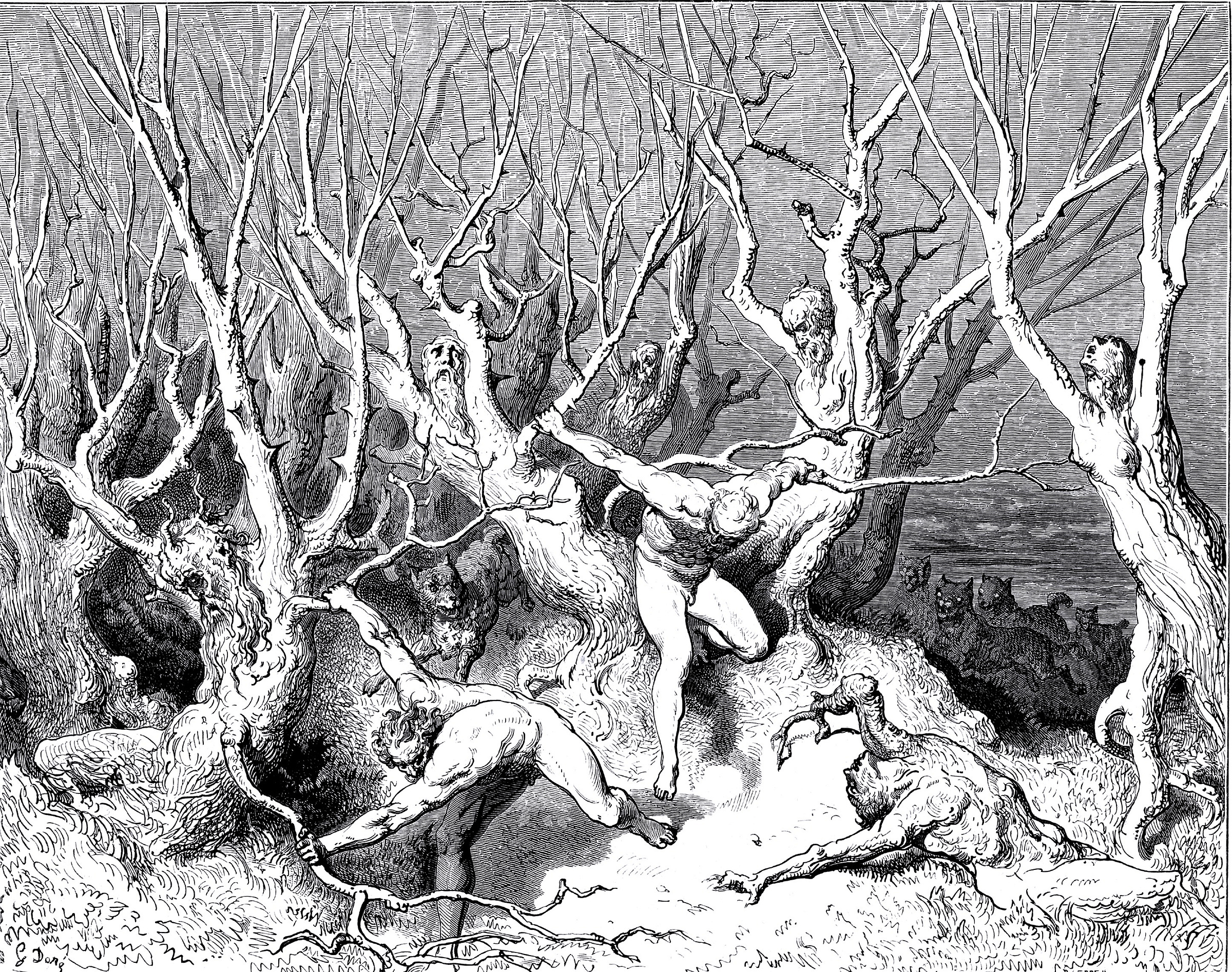

They were cut off by the sound of an approaching roar, of running and the cracking of branches as two running naked souls flew past them, scratched indiscriminately, calling out to each other. These are the Profligate, or those guilty of dissipation and reckless waste of resources, another form of Violence to Self; like the Suicides, they did not value their resources and wasted - maliciously - the opportunities entrusted to them.

What then is the difference between these Profligates and the Spendthrifts of Circle IV? The Spendthrifts were in the circles of incontinence, and were not malicious in their intent, but the Profligates are a willful and malicious destruction of resources.

The first running shade called for death to come quickly (XIII.118); this is Lano of Siena. He called for death, but think of the impossibility of relieving suffering through death in Hell.

The second running soul, Jacopo da Santo Andrea, called out to the first before falling, “Lano, your legs / were not so nimble at the jousts of Toppo!” (XIII.120-121), indicating that he is running as fast as he can, faster even than he did in running from battle. Jacopo was said to have “prodigally - or rather, wickedly and insanely - squandered and wasted an inestimable treasure of wealth.”4

These two were being chased by dogs who overtook them and tore them to bits; as they wasted and “scattered” resources in life, so are they “scattered” in Hell by being dismembered.

Dante and Virgil went to a nearby bleeding bush, broken from the crashing and running souls.5 This unnamed soul addressed Jacopo, questioning why he had to be hurt for Jacopo’s sins as Jacopo ran past trying to get away from the dogs. He asks Dante and Virgil to collect the broken pieces of its branches and to place them around his trunk. This soul was from Florence:

My home was in the city whose first patron

gave way to John the Baptist; for this reason,he’ll always use his art to make it sorrow;

and if - along the crossing of the Arno -

some effigy of Mars had not remainedthose citizens who afterward rebuilt

their city on the ashes that Attila

had left to them, would have travailed in vain.

XIII.143-150

The first patron he references is the god Mars, whose temple gave way to John the Baptist, meaning that the reverence for the pagan ways was replaced - literally in the church built over the temple, and figuratively in the spirit - by Christianity. Because of this, Mars will use his arts of war and strife to make Florence suffer.

Florence’s change of patron indicates its transformation from stronghold of martial excellence (under Mars) to one of servile money-making (under the Baptist).6

When the Christian church was put up in place of the temple of Mars, Florentines kept in mind the due reverence for the original statue of Mars; it was not to be broken or destroyed for fear it would cause suffering to the city. Dante references Florence being destroyed by Attila, during which the statue - which had been placed near the river upon the building of the church, fell into the river. When Florence was rebuilt in the coming centuries, they rescued the statue (what remained of it) from the river and again put it on a pillar. If one of the arts of Mars is civil war, then both the Suicides and Profligate represent that strife toward themselves through violence.

We close the Canto with the confession of this unnamed soul who made of his own home his place of death.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

“The world says: "You have needs -- satisfy them. You have as much right as the rich and the mighty. Don't hesitate to satisfy your needs; indeed, expand your needs and demand more." This is the worldly doctrine of today. And they believe that this is freedom. The result for the rich is isolation and suicide, for the poor, envy and murder.”

~ From The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoyevsky

What is suicide?

It is the ruination of the body in an attempt to banish inner torment; it is the will’s stubborn refusal to surmount the trials of the world.

Thus far in our journey, we have encountered but one name who took his own life—Seneca. The great Stoic, compelled by Nero’s command, met death as one might expect of a philosopher: with dignity, without fear, in full acceptance, and with a mind prepared. Yet his end does not fully align with the definition of suicide we considered at the outset. Seneca did not surrender to despair, nor did he flee from suffering; he obeyed a decree. His death was not an act of abandonment but one of resolve, modeled upon the departure of Socrates, who likewise was sentenced to die by the Athenian court. Unlike Seneca, however, Socrates was given the chance to flee—and refused.

Neither Seneca nor Socrates took their lives out of despair; both met death with resolve, submitting to what they perceived as necessity. They did not seek escape but answered when fate summoned them, embracing death as an extension of their philosophical convictions rather than a surrender to suffering.

They faced their fate virtuously.

I. Dante Against Virgil: Free Will Against Fate

In this canto, Dante appears to challenge the pagan notion of fate, including Virgil’s own conception of it. The scene is unmistakably drawn from Aeneid Book III, where Aeneas, upon encountering a plant, discovers it to be the transformed body of Polydorus, son of Priam.

Priam, seeking to secure his son’s safety, had sent Polydorus to the Thracian king along with Trojan gold. But the allure of wealth proved stronger than loyalty—the Thracian king betrayed Priam’s trust, murdered the young prince, and left his body unburied. Deprived of proper rites, the corpse decayed and took root, sprouting into a myrtle. When Aeneas unknowingly breaks a branch, Polydorus, trapped in his suffering, speaks through the wound, recounting his tragic fate. Aeneas, moved by piety, ensures that the prince receives the burial he was denied in life, granting his restless soul peace.

The parallels with Virgil’s masterpiece do not end there. Once again, we find ourselves in a shadowed, foreboding forest—this time guarded by the Harpies. These ominous creatures, like the ones we encountered in the previous canto, bear a body of mismatched parts, neither fully human nor fully beast, embodying disorder and unnatural transformation.

One of the Harpies in Virgil’s Aeneid tries to convince the surviving Trojans that their journey is doomed and worthless since they are going to die of starvation. She infuses depression even before their journey had actually begun.

In this circle of the damned—those who committed violence against themselves—the Harpies embody the tormented mind consumed by despair. Remember that the sins we encounter in Lower Hell arise from Medusa and the Furies, both symbols of despair’s petrifying grip. The Harpies, perched among the gnarled branches of the self-damned, serve as a symbol our mind in a state of hopelessness. As Dante says in one of my favourite lines of Inferno II:

And just as he who unwills what he wills

and shifts what he intends to seek new ends

so that he’s drawn from what he had begun,so was I in the midst of that dark land,

because, with all my thinking, I annulled

the task I had so quickly undertaken.Inferno II, lines 37-42

Dante tells us that there is a difference between pagan philosophy and Christian theology. In Virgil’s vision, Polydorus was bound by an unalterable fate—his murder was inevitable, his destiny sealed. All that remained was for Aeneas to perform the proper burial rites, granting him rest. In contrast, Dante’s universe is one of moral accountability, where the soul’s fate is not dictated by an unyielding force but shaped by the will and its choices.

We can see this when we meet Pier della Vigna…

II. Pier della Vigna and Boethius

Pier della Vigna served as a notary at the court of Frederick II, rising swiftly through the ranks. Appointed judge and protonotary, he spent over two decades as the Emperor’s most trusted minister and confidant. Yet at the height of his power, he was cast into prison, accused of embezzling from the treasury.

Unable to bear the loss of his status, wealth, and honor, Pier della Vigna succumbed to despair and took his own life.

Boethius, too, was imprisoned under similar circumstances. Once an esteemed advisor to Theodoric the Great, he was falsely accused of conspiracy and condemned. His life turned upside down overnight. The parallel between their fates is striking—both men fell from imperial favour, both faced ruin. But where Boethius turned inward, composing The Consolation of Philosophy in his captivity, Pier della Vigna surrendered to despair.

Both men met tragic ends, but their attitude to life was radically different. Boethius’ Consolation begins with Furies surrounding him in his cell, convincing him that despair is near, lulling him to slumber by their worthless songs; he tells them off, thus allowing Lady Philosophy to come to the rescue of his soul. Furies, Harpies, failed to conquer Boethius, but succeeded in forcing Vigna to surrender.

Some final thoughts in the next section…

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Jacopo da Sant’Andrea and Lano da Siena

There is an important distinction between the spendthrifts we find earlier in Inferno among the avaricious and those whom we find here. The spendthrifts squandered their resources without direct self-harm, while Jacopo’s and Lano’s actions were driven by the desire of violence against one’s own property.

More on each character and what they committed in the Characters section.

Suicide and Exile

Dante knew well the despair that follows the loss of everything. Exiled from his home, stripped of what was rightfully his, he wandered as an outcast. The voices of Pier della Vigna and Boethius must have echoed deeply within him—one surrendering to despair, the other turning suffering into wisdom. Between these two fates, the mind teeters, swaying over the abyss.

In Purgatorio, we will encounter the Roman statesman Cato, who, despite having taken his own life, stands not among the damned but in a guiding role for our companions. Cato took his own life in defiance of tyranny, an act of unwavering spiritual integrity. And yet, what is he doing in Purgatory, guiding souls toward salvation? Should he not, according to the logic of this circle, be here among the trees of the suicides, his spirit bound within twisted branches?

Dante’s moral architecture rests on the principle that one is punished not for the final act itself, but for the motive that led one to it. Seneca, Socrates, Cato - all had taken their own lives, but they are not found among the damned trees, because their action was done not out of despair but out of necessity.

Mind and Body

In modern discussions on consciousness and artificial intelligence, one question proves particularly difficult to answer: Can artificial intelligence attain human-level intelligence without a physical body?

The mind and body are deeply intertwined—severing one from the other risks the destruction of both.

If These Trees Could Talk

The way the trees communicate give us so much insight into the minds of those who are in despair. They talk through pain and about pain.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

Therefore my master said: “If you would tear

a little twig from any of these plants,

the thoughts you have will also be cut off.”

Characters:

- Harpies - Creatures of the Strophades islands with the bodies of monstrous birds and the heads of women, they defile what is before them.

- Pier della Vigna - (1191-1249) Minister to Emperor Frederick II, he was unjustly accused of defamation and embezzlement, was blinded and imprisoned, and committed suicide. One account of his downfall even says that he was accused of conspiring with the pope to poison Frederick II, an accusation which was generally disbelieved.

- Lano of Siena - Lano of Siena was a notorious youth who, along with some friends, “belonged to the notorious Brigata Spendereccia, or ‘Spendthrift Club,’ of Siena, and squandered all his property in riotous living”7 - into utter ruin. He died in the battle between the cities of Arezzo and Siena, while running for his life in cowardice; we will see other members of this infamous band in a later Canto (Inf. XXIX.130-131).

- Jacopo da Santo Andrea - Known for squandering riches, one story about Jacopo relates that upon hearing that he would be visited by a group of nobles, being unprepared, he malevolently called for his estate to be set afire, including the homes of the surrounding peasants. He told the shocked nobles that it was a celebration of their arrival. Benvenuto da Imola, the 14th century scholar, says of him that “he was more violent and more foolish than Nero; for Nero had the houses of the city burned, but he his own.”8 Jacopo was possibly put to death by order of Ezzelino, whom we saw in Canto XII (Inf XXI.109)

Sayers Hell 153

Just as I snapped the first shrub from its roots to extract it, I noticed

something that made me bristle with fear, and which makes an astounding

story; for dark blood started to ooze, dripping downwards in large drops,

staining the soil with its putrid gore. A shudder of ice-cold

horror shivered my limbs.

Aeneid III.26-30

Sayers Hell 154

Singleton 220

He has been variously identified - though mostly considered as an unknown - as either Lotto degli Agli, a judge who hanged himself after he gave an unfair ruling, or Rocco de’ Mozzi - both of Florence - who hanged himself after his prominent business failed.

Musa Inferno XIII.143n.

Singleton 218

Singleton 220

Dante's vision for the fate of suicides is a harrowing image which will haunt me for a long time.