From Homer to Nabokov: What Every Writer Fears

Why there will be no second Hugo, no second Tolstoy, no second Proust...

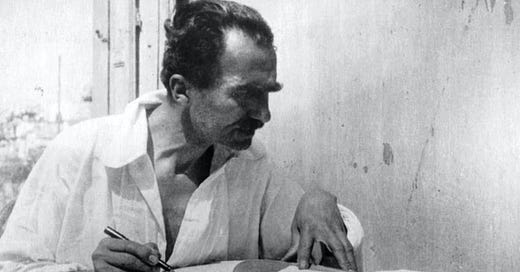

‘One day without a clear purpose in mind I took a pen and started writing. This was a crucial moment in my life. Thoughts, memories of important times, of a girl, the smell of her body, her red lips like two drops of blood. Whatever haunted me had left me now; it was laid on paper unable to escape’

Those are words of a Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis, who was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature nine times and is considered to be the Homer of 20th-century Greek literature.

Kazantzakis is one of the two types of writers that appear on the pages of history. The first type is perfectly summarised by the Russian word ‘gra-pho-man’ (графоман). In fact that word comes from Kazantzakis’s mother tongue Greek and consists of two words γράφω (grapho) - to write, and μανία (mania) - madness. The term means the obsessive impulse to write. In psychiatry, graphomania is used when the patient writes a meaningless succession of words or nonsense. In a day-to-day conversation, Russians use this word to describe a vulgar, talentless and narcissistic writer. A writer who might have written a bestseller, not because of having exceptional talent, but in spite of it. In fact, most of the modern bestsellers are the result of graphorrea.

The British art historian Kenneth Clark, when asked how he would define the word ‘civilisation’ replied:

‘I don’t know how to define it, but I will certainly recognise it when I see it.’

Clark’s words can be applied to great writers. It takes only a page or two to recognise Nabokov’s genius or Dante’s exceptional imagination. They are writers possessed by genius, or the second type of authors. The problem with the genius is that it cannot be explained, only experienced. Russians say ‘It’s better to experience it once with your own eyes, than to hear it described thousand times’ In other words, it’s better to see Kubrick’s Space Odyssey once with your own eyes, than to hear your friend describing it thousands of times.

Yes, genius cannot be explained, but we can witness commonalities that unite Nabokov with Dostoyevsky or Proust with Kazantzakis. The works of geniuses are expressions of the things that haunted them, memories that shaped them, emotions that changed them. While graphomans’ scribblings die as their authors pass away, Nabokov’s stories are littered with idiosyncrasies of his character; Dostoyevsky’s with his anxieties; and Proust’s with his sensitivity to memories. The works of geniuses, in contrast, remain alive, even when they die, because their personalities continue to breathe on the pages of their masterpieces.

I have to say, I’m scared of mediocrity. I’m scared of being or becoming a graphoman. The reason for my fear is not because I consider myself to be exceptional, absolutely not. I’m scared of mediocrity, because I define that word as ‘playing with someone else’s rules’. I fear that one day I will turn back and look at what I filmed, wrote, or said and realise that my thoughts were someone else’s opinions, that my life was not authentic to who I was, but instead was a mimicry of someone else’s.

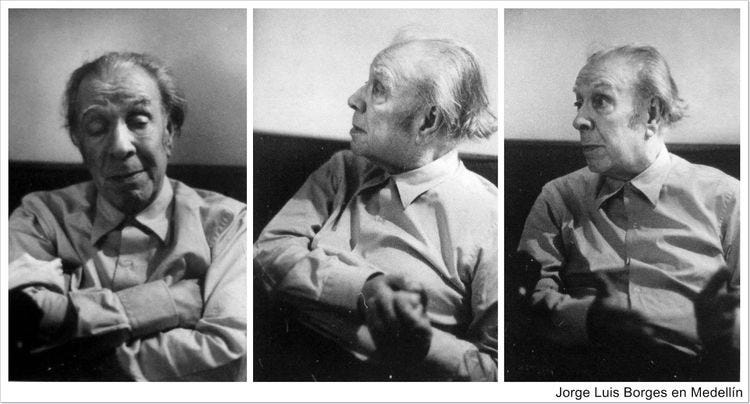

I fear that one day I will be in a situation similar to that of Jaromir Hladik, a mediocre Czech writer, from Borges’s short story The Secret Miracle. In 1939, Hladik was sentenced to death by Gestapo for his Jewish origins (his real surname was Jaroslawski) and for opposing Anschluss. Instead of executing him there and then, Gestapo chooses to torture him by telling the precise date when he is going to stand in front of the firing squad. For the first six days, Hladik pictures the infinite variations of his execution, until ‘he dies thousands of deaths’

Hladik, as I mentioned, was a mediocre writer, with several lacklustre and forgettable published novels. Before his arrest by Gestapo, Hladik was writing a play called The Enemies, which was unfinished. On the last night before his execution, this minor writer remembers his main ambition in life - writing. He realises that none of his works truly express who he really was. In his cell he prays to God, asking him to grant one more year so he could complete his unfinished play.

if I am not one of Thy repetitions or errata, then I exist as the author of The Enemies. In order to complete that play, which can justify me and justify Thee as well, I need one more year. Grant me those days, Thou who art the centuries and time itself.

That night, he dreams of going to the Clementinum library, where the librarian has gone blind looking for a single letter that represents God. Someone returns an atlas to the library; Hladík touches a letter in it and hears a voice that says1, "The time of your labor has been granted"2

The next day he is awakened by a soldier who takes him to the execution. Hladik thinks that his prayer was left unheard, that the dream he had was as good as fiction. But on the very last second, the world freezes. The firing squad stands still, the birds remain in the sky but cease to move, Hladik himself feels conscious but unable to utter a word. This was the time that God granted him, he had to begin his work:

“He had no document but his memory… He did not work for posterity, nor did he work for God, whose literary preferences were largely unknown to him.

Painstakingly, motionlessly, secretly, he forged in time his grand invisible labyrinth. He redid the third act twice. He struck out one and another overly obvious symbol-the repeated chimings of the clock, the music.

No detail was irksome to him. He cut, condensed, expanded; in some cases he decided the original version should stand. He came to love the courtyard, the prison...

He completed his play; only a single epithet was left to be decided upon now.”3

Once Hladik conceives the final epithet, the time bestowed upon him by God reaches its conclusion, marking the completion of his unseen but perfected masterpiece. With the firing of shots, Hladik's life comes to an end.

In the span of just two-pages, Borges transforms this minor writer from a graphoman to a genuine writer. ‘In every man hides a prophet’ wrote Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran, and whether that life is meaningful or not depends on how well he will be able to articulate that prophecy. It’s true, my dear reader, nobody will ever read Hladik’s ‘prophecy’, but the point isn’t the fame, that’s not what Borges conveys, the point is that the primary aim of a great artist is to articulate who he really is.

This is the reason why every book written by Dostoyevsky, for example is based on the ideas or experiences he witnessed in his life. Goethe’s entire story of Werther is based on his own love-affair. This is why readers who open Dante’s Divine Comedy for the first time are shocked to discover that many characters whom Dante put in Hell were people he knew in his lifetime. It’s the same with Nabokov, Proust, Joyce, and Borges himself.

What makes Proust Proust or Nabokov Nabokov is how deeply they experienced life and how uniquely and masterfully they converted those experiences into words. This is why there can be no other writer who could write like Kafka, or Joyce, or Didion. Nobody will ever be able to see grand narratives like Tolstoy, or to create fantastical worlds exactly like Tolkien. Those geniuses articulated who they were in their works and will never be coming back again.

My biggest fear in life is not that I will never become as well-known or as recognised like geniuses mentioned before. No, that would mean that I’m repeating Hladik’s mistake. That would mean I’m chasing goals of graphomans. Moreover, that would mean that I am already a graphoman, before even publishing anything. My deepest fear is that I won’t articulate who I am to my own self. I always remind myself that most writers are not as lucky as Hladik, they don’t get second chances to correct their mediocrity. Most of us don’t realise that (in words of Walt Whitman) …

‘…the powerful play goes on, and [we] may contribute a verse.’

A question that I ask myself repeatedly (to paraphrase the question of the fictional professor Keating):

‘What will Vashik’s verse be?’

Confide tibimet

Proofread and edited by Lisa Statler

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Secret_Miracle

Borges, Collected Fictions (translated by Andrew Hurley)

Borges, Collected Fictions (translated by Andrew Hurley)

Do you want to keep a journal? (Patreon)

6 Paintings I Carry in My Journal All Time

I’ve been journaling for the past 15 years of my life. By saying this I mean that for the past decade and a half, I’ve been sitting down, consistently, every day, and writing my thoughts and ideas into my notebook.

If you would like to begin your journaling journey, but don’t know where to start, how to stay consistent, or which type of journaling suits you, consider subscribing to my Patreon page.

I’ve made several ‘Guided journaling’ videos, where we sit down and journal together, I give journaling tips based on science, and I share some very personal pieces of advice based on my own journey.

I think it is an error to categorize all writers either as geniuses or frauds. I think most of us are rather humble craftsmen. Epitomizing or mystifying the work of the "greats" does them a disservice. But the call to find "the prophet inside" or to give your single verse to the world is a good reminder in our world of distraction or general aimlessness.

'most of the modern bestsellers are the result of graphorrea' this!

What a wonderful post this is! Really, thought-provoking and moving♥️