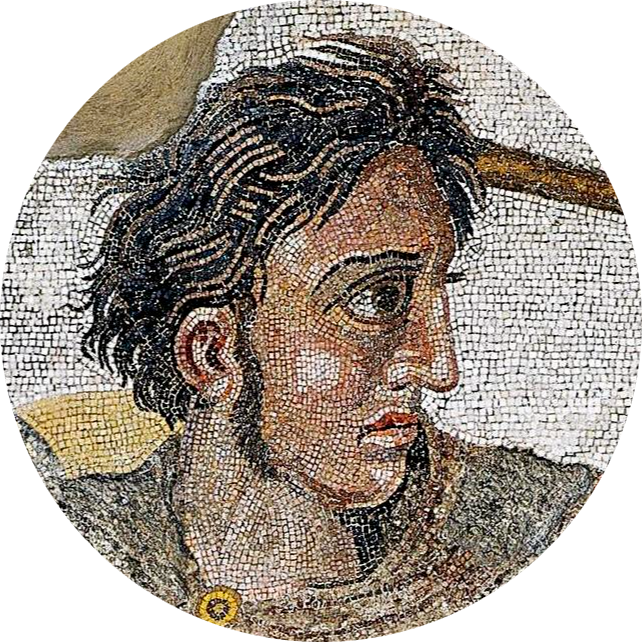

At the age of 33, Julius Caesar stood in front of the statue of Alexander the Great and wept. Alexander had built the greatest empire the world had ever known by the age of 32 and as Caesar stood before the memory of his hero, he questioned, "Have I achieved anything memorable?"1

Only an ambitious person can grasp the true cause of Caesar’s tears. He wept not because he was a year older than Alexander, but because he doubted if he would ever achieve anything worthy of remembrance. The uncertainty of falling into oblivion hovers above the ambitious minds throughout their life. It is easy to forget that no oracle or seer told Alexander that he would reach greatness by the age of 32, same as no one said to the great scientist Marie Curie that she would forever change the course of humanity by her discoveries in radioactivity.

They knew that they could sink into oblivion and this uncertainty of whether they were going to be remembered or not caused permanent anxiety to them. Throughout human history, this fear forced ambitious individuals to imitate their role models and search for secret skills that their heroes possibly possessed.

It often seems that great figures of history were assisted by some type of divine force. We often wonder whether there is some kind of secret knowledge, that gave conquerors such as Alexander or Caesar; or artists such as Da Vinci or Michelangelo an edge over everyone else.

It seems that the answer is ‘Yes’ when it comes to Alexander. It seems that there was a secret, or better to say, an exclusive knowledge that he possessed that gave him an edge over the ‘common man’.

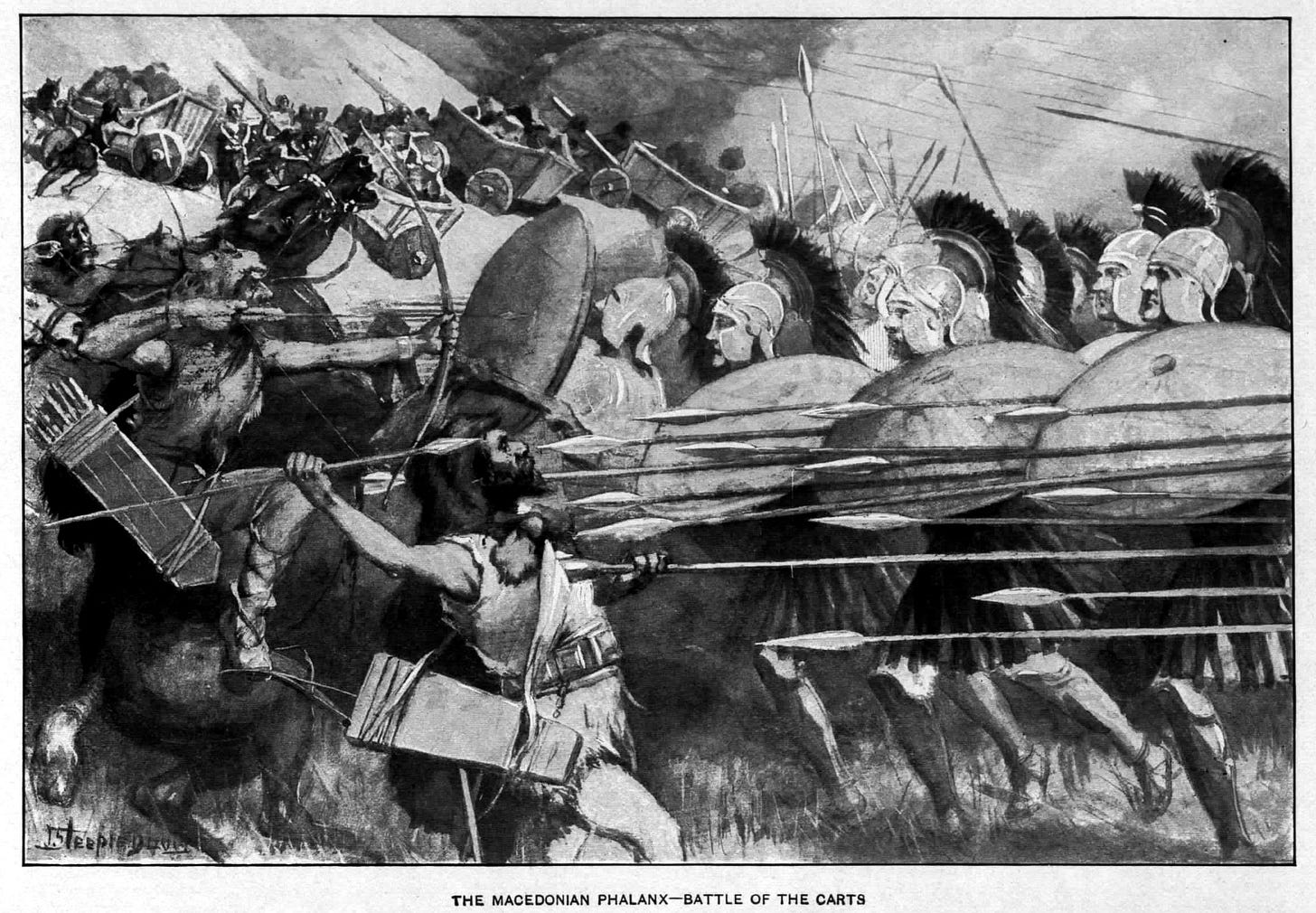

Alexander was taught by the great philosopher Aristotle and in Aristotle’s Lyceum existed two types of knowledge2: the first kind of knowledge was written down and included treatises such as Morals, Of Politics, and others, while the second was esoteric and was passed orally only to the selected few people.

What was this exclusive knowledge so powerful that it could only be conveyed orally, never written down?

We may not know, but we do know that Alexander the Great wrote a letter scolding Aristotle when he found out that his tutor published parts of it. Here’s the letter that Alexander wrote to Aristotle as quoted by Plutarch:

Alexander to Aristotle, greeting.

You have not done well to publish your books of oral doctrine; for what is there now that we excel others in, if those things which we have been particularly instructed in be laid open to all?

For my part, I assure you, I had rather excel others in the knowledge of what is excellent, than in the extent of my power and dominion. Farewell.

When I first read this letter I was left speechless for a while. Nietzsche once wrote that if an idea does not cause you insomnia then the idea was not powerful enough.

There are three crucial ideas in this four-sentence letter that left me sleepless for days. First, Alexander confirms to us that an exclusive piece of knowledge exists; second, that those who possess it have an edge over those who do not (‘what is there now that we excel others in…’); and finally third, perhaps the most amazing part of this letter, is the fact that Alexander tells to his tutor that he would rather excel in this knowledge than ‘in the extent of my power and dominion’.

I've thought a lot about that last idea, in particular. Alexander the Great, the most powerful conqueror in history, said that he would have rather excelled in this mysterious esoteric piece of knowledge than in the extent of his empire?

Plutarch writes that Aristotle, in his reply to Alexander, said that his student should not worry about this knowledge being made public, since only those who will have proper instruction and explanation will fully understand it.

What knowledge Alexander and Aristotle were referring to is a matter of speculation. I do not want to disappoint my reader but it is unlikely we will ever read the book that prompted Alexander to write an angry letter to his tutor.

After spending several sleepless nights thinking about this I came to a thought that could possibly explain what Aristotle was teaching to his narrow circle of students of his Lyceum.

If we pay close attention to the words that Alexander uses in his letter we can see that in the sentence ‘I had rather excel others in the knowledge’ he uses the word ‘to excel’ which implies that this knowledge required exercise, discipline, and regular practice. This is crucial because, in our modern culture of instant gratification, we tend to imagine mysterious knowledge as a quick fix, similar to the pill he took in the film "Limitless," where the protagonist achieves remarkable results without any discipline, effort, or by using the power of his own will.

In contrast, the knowledge that Alexander wanted to excel in required effort, discipline, and, as Aristotle’s reply shows, proper instruction.

This led me to the next thought: that this mysterious knowledge that gives one an edge over others is often hidden in plain sight. It is likely that we will never find out the truth about Aristotle’s esoteric teachings, but we can imagine what they could be like if we look at ideas of Stoic philosophy as an example. Let’s just imagine what it would be like if stoicism was kept secret from us.

No matter how rigorously one might apply the principles of stoicism to their life, anyone who is familiar with the teachings of Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, or Epictetus knows that their lives would have been significantly poorer without them. From my own personal experience, I can say that the Stoic ideas had a profound influence on me despite my often undisciplined and irregular practice of them.

In this sense, those who are versed with Seneca or Epictetus and practice their ideas have an edge over those who are yet to discover Stoic practices. This is the mystery of Stoicism - it does not have any supernatural teachings but its practices give you an almost magical power of self-control.

My reader might raise a question of whether I am prepared to trade my house or possessions for the stoic teachings in the same way as Alexander was ready to trade the extent of his empire?

Perhaps, the answer as of today would be a ‘No, I am not ready yet’, but I am certain that I would trade many books from my library in exchange for keeping the volumes written by the great stoics if I had to.

When I first read Alexander's letter, I was captivated by the thought of the untold wisdom he might have possessed. But then I realised that before chasing after hidden knowledge, I must first learn and practice the wisdom that is already available to me.

In fact, I have Alexander’s favourite book in my library and it is quite likely you do own it as well. Alexander read and re-read this volume after Aristotle introduced him to it. This book taught him how to live, how to fight, and how the gods influence destinies. He kept this book under his pillow throughout his conquests - that book is Homer’s The Iliad.

At some point in our lives, we all weep like Caesar. We all stand in front of a statue of our hero and cry that we have not achieved greatness that will make us remembered. In these very moments, we must not despair and need to remind ourselves that our role models have left us clues that are not buried under the sands of mystery but lie open if we are willing to see it.

Confide tibimet.

Proofread and edited by Lisa Statler.

I slightly paraphrased the quote. The original by Plutarch goes like this: “His friends were surprised, and asked him the reason of it. ‘Do you think,’ said he, ‘I have not just cause to weep, when I consider that Alexander at my age had conquered so many nations, and I have all this time done nothing that is memorable?’

What follows comes from Plutarch’s The Life of Alexander. By ‘types of knowledge’ I do not mean Aristotle’s classification of knowledge types but the way they were transmitted.

Whenever we miss the mark in our efforts to live in practice the philosophy we aspire to, it is important to realize it, assess where and why we missed the mark, and redouble our efforts to do better. However, we must not beat ourselves up about it. We can give ourselves a “get out of jail free” card and move on.

We will miss the mark dozens of more times in our lives, that is part of being human.

Caesar's question, "Have I achieved anything memorable?" resonates with all who possess a touch of reason. Who among us wouldn't wish to leave a lasting imprint, to carve out a place in the annals of human history? Yet, such a destiny is reserved for the few—the chosen ones—those endowed with gifts from above and driven by unwavering will and relentless effort.