How Love Directs Our Attention

(Purgatorio, Canto XVII): the Architecture of Purgatory and why love is more rational that reason

Love is a canvas furnished by nature and embroidered by imagination.

~ Voltaire

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Seventeeth Canto of the Purgatorio, Virgil begins his discourse on love. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

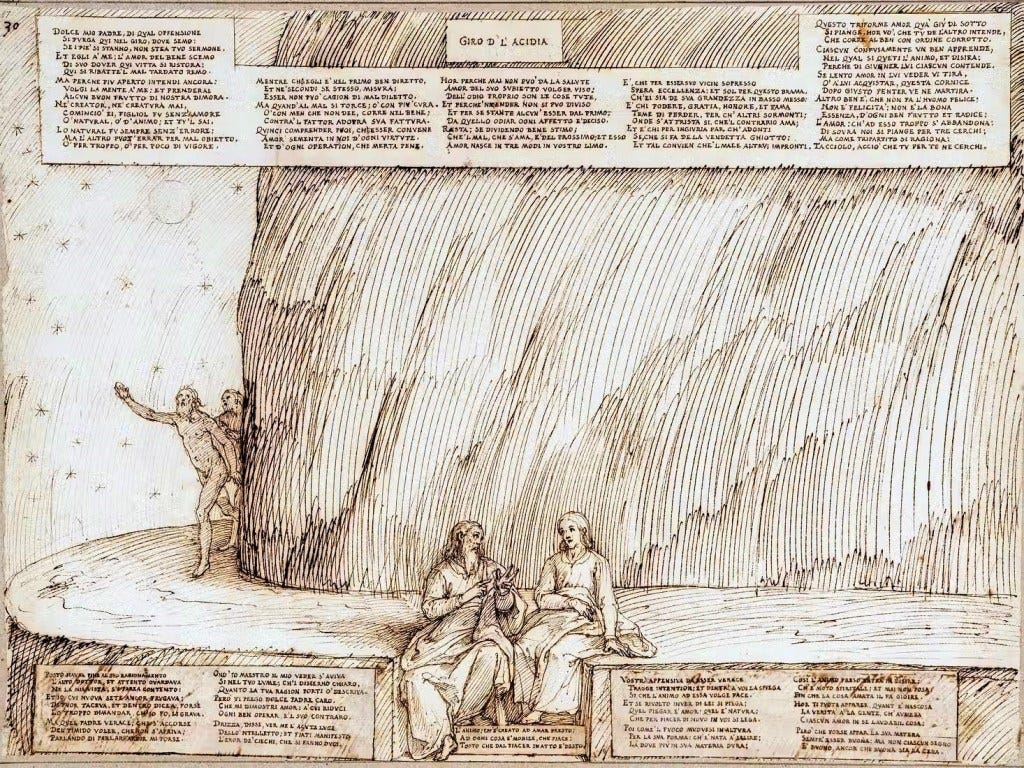

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

The smoke clears in the terrace of the Wrathful - Dante’s visions of the bridle of Wrath - Procne, Haman, and Queen Amata - A bright light dazzles Dante - The Beatitude of the third terrace Beati Pacifici - The Angel of Meekness wipes another P from Dante’s forehead - The sun has set and it is time to rest - Virgil’s discourse upon the nature and function of love and the architecture of Purgatory.

Canto XVII Summary:

As the light of the setting sun began to break through the stinging smoke that Dante and Virgil had found themselves within on the third terrace of Wrath, Dante spoke of mountain fog as it began to dissipate, comparing his sight to the lowly and—as was commonly thought in the middle ages, sightless—mole:

And you know well that the mole cannot see at all, for nature will not open the membrane that is over its eyes, so that these are worthless, because they are covered.

Brunetto Latini

Dante followed Virgil as guide in that semi-blind state, and walked into the evening light that cast a shadow at the foot of the mountain.

O fantasy, you that at times would snatch

us so from outward things—we notice nothing

although a thousand trumpets sound around us—

who moves you when the senses do not spur you?

A light that finds its form in Heaven moves you—

directly or led downward by God’s will.

xvii.10-15

Dante called out to the imagination as his second set of visions on the terrace of Wrath commenced; just as he had visions of the exemplars, or whips, of meekness upon his entrance, here he will experience their deterrents, the bridles, as they exit. This power of imagination was such that any strength of external forces, no matter how intense, could not detract from the all-encompassing nature of the vision. How could this be, when the senses brought in no stimuli?

In scholastic psychology, deriving from Aristotle’s De anima, the imaginativa or phantasia is conceived as one of the interior senses, the specific function of which is to store or retain in the mind the forms or images that are received through the exterior senses.1

In this vision, the light from God and the Empyrean realm would send images directly to the one receiving:

This “envisages the uncommon experience of receiving into the imaginativa images that are not received from any exterior sense. And the answer which follows recognizes that this by-passing of the exterior senses is possible if a light from above “rains down” directly into the phantasy, bringing such images as Dante now sees in the three scenes described in the following verses.”2

The first vision, from classical antiquity as found in Ovid, is the story of Procne; sister of Philomela and wife and Queen to King Tereus, Procne killed her own son in retaliation against her husband's horrific actions.3 As Ovid tells it, Procne wanted to see her sister Philomela, so King Pandion traveled to Athens to escort her back to Thrace:

On the way back to Thrace he ravished her and, to prevent her revealing what had happened, cut out her tongue and abandoned her, informing Procne on his return that her sister was dead. Philomela, however, contrived to weave her story into a piece of cloth and thus conveyed the truth to Procne. The latter in fury killed her son and served up his flesh to his father Tereus, who partook of it, unconscious that he was feeding on his own child. Learning from Procne what she had done, Tereus pursued her and Philomela with an axe and was about to slay them, when in answer to the prayers of the two sisters all three of them were metamorphosed into birds.4

As this image concluded Dante’s mind withdrew even more fully as the lofty visions continued to ‘rain down’ into him; the next one stemmed from the Old Testament book of Esther; some of the details of the vision were of Dante’s own creation. He saw Haman, crucified, his face filled with wrath even as he was dying. Haman was a minister of the Persian king Ahasuerus—who “reigned, from India even unto Ethiopia, over an hundred and seven and twenty provinces.”5 Haman’s anger stemmed from the acts of Mordecai, a Jewish man, who did not bow before the king as commanded. Esther, Queen to Ahasuerus, was the adopted daughter of Mordecai.

Haman…was enraged that the Jew Mordecai did not bow down to him and obtained from Ahasuerus a decree that all the Jews in the Persian Empire should be put to death. After the failure of this attempt to compass the destruction of the Jews, Haman, through the intervention of Esther and Mordecai, was hanged on the gibbet he had prepared for Mordecai.6

As this image burst like a bubble, the third vision came to Dante’s mind; that of a weeping Lavinia, daughter of King Latinus from Virgil’s Aeneid. She had been engaged to the Latin hero Turnus, over whose supposed death her mother, Queen Amata committed suicide in her wrath, knowing that would mean Lavinia’s marriage to the rival Aeneas was certain:

When, looking out from the palace, the queen sees the enemy coming,

Walls being scaled, flames leaping from rooftop to rooftop, but nowhere

Any Rutulian troops to oppose, any forces of Turnus,

She, hopes unfulfilled, believes Turnus has perished in combat,

And, her mind shattered by grief’s sudden upsurge of horror,

Screams out that hers is the blame, she’s the cause, she’s the source of disaster,

Mindlessly raving out torrents of words in the madness of sorrow,

Rending her purple regalia with hands that will now end her life’s span:

She’s slung a noose for a hideous death from a beam in the ceiling.

Once this catastrophe’s known to the poor, sad women of Latinum

First to react is Lavinia, whose hand rips her own golden tresses,

Tears at her rose-colored cheeks.

Aeneid xii.595-606

Slowly these visions slipped away as Dante saw light strike his eyes:

Even as sleep is shattered when a new light

strikes suddenly against closed eyes and, once

it’s shattered, gleams before it dies completely,

so my imagination fell away

as soon as light—more powerful than light

we are accustomed to—beat on my eyes.

xvii.40-44

That light, even greater than that of the sun, struck his closed eyes as he came out of his visionary trance; he heard a voice directing him where to turn his steps. It was the Angel of Meekness, exhibiting the kindness that is the opposite of Wrath; the voice claimed his full attention, and left him with a restless eagerness to know more, a restlessness that would continue until its desire was fulfilled. Virgil urged Dante to follow that voice, which, unbidden, called out to help them before they were even able to ask:

Zealous liberality may be noted [in] giving without being asked; because when a thing is asked for, then the transaction is, on one side, not a matter of virtue but of commerce, inasmuch as he who receives buys, though he who gives sells not; wherefore Seneca saith ‘that nothing is bought more dear than that on which prayers are spent’.

Dante Convivio I.viii.16

As darkness was about to fall, they took the first step up to the next terrace, when Dante felt the familiar wing fan his face; the third P had been removed as the Angel blessed him. They heard the Beati Pacifici, the blessing of the Peacemakers who did not feel sinful wrath, that is, mala ira, an unjust anger.

Anger is properly the name of a passion. A passion of the sensitive appetite is good in so far as it is regulated by reason, whereas it is evil if it set the order of reason aside.7

As the sun set further and the stars began to show in the sky, Dante felt his strength fail him and tiredness overtake him. Here was the Law of the Mountain in effect, in which all who traveled must rest at night.8 They had reached the last step leading to the fourth terrace, and Dante stood as immobilized, listening for any activity.

Virgil and Dante reach the last step of the stairway and stand facing toward the next terrace, the fourth, just like a ship that touches shore. That is, they reach the edge of this central terrace, so that, as they look ahead, facing toward the fourth terrace, they have that terrace and three beyond it ahead of them. This is very carefully planned by the poet, for it serves, by exact position, to group the sin purged on this fourth terrace, sloth, with the sins purged in upper Purgatory.9

Dante took advantage of this still moment, this liminal space—that still space—between that which was below, and the place they had yet to traverse. In this space, we, reader, will enter the very heart of Purgatory, the very center of this great epic poem. And what we find here, in Virgil’s great exposition upon the architecture of Purgatory, as well as his Discourse on Love, is the key to unlocking the entire poem. If at no other point we take the time to explore the underlying philosophy of the poem, this is the place to do so.

The general exposition of the purgatorial system is thus made at a point in the journey when the wayfarers are obliged to pause, even as was the case when the punitive system of Hell was expounded.10

Because Dante placed Virgil’s discourse on love at the heart of the Commedia, the poet invites his readers to use love as a hermeneutic key to the text as a whole…[he] invites us to perform the interior transformation which the poem dramatizes in verse and symbol. He does so by awakening in his readers not only a desire for the beauty of his poetic creation, but also a desire for the beauty of the love described therein. In this way, the poem presents a pedagogy of love, in which the reader participates in the very experience of desire and delight enacted in the text.11

Dante asked what the sin of the fourth terrace was, and asked Virgil to use this time to the best of their advantage.

And he to me: “Precisely here, the love

of good that is too tepidly pursued

is mended; here the lazy oar plies harder.

But so that you may understand more clearly,

now turn your mind to me, and you will gather

some useful fruit from our delaying here.

xvii.85-90

That “love of good that is too tepidly pursued” is that of Sloth; those souls will be made to work toward their purification with zeal in order to contrast their spiritual lethargy. Let us, with Dante, gather that excellent fruit.

Sloth is a kind of sadness, where a man becomes sluggish in spiritual exercises because they weary the body.12

My son, there’s no Creator and no creature

who ever was without love—natural

or mental; and you know that,” he began.

The natural is always without error,

but mental love may choose an evil object

or err through too much or too little vigor.

xvii.91-96

For Virgil to claim that neither God nor anything in creation lacked love may seem a bold statement; yet it exemplifies the ideal set forth by St. Augustine in his conception of ordo amoris and rightly ordered love. This is the love that is the whole theme of the Divine Comedy; in short, that any movement toward any desire, whether it be toward good or toward something evil, is based on one’s love toward that thing.

Every agent acts for an end…now the end is the good desired and loved by each one. Wherefore it is evident that every agent, whatever it be, does every action from love of some kind.13

Love is “the principle upon which all His creatures pursue the goals of their existence. The following passage expounds Dante’s doctrine that, in the case of human beings, love, the function of the will, is the cause not only of virtue but also of sin.”14

Virgil names two kinds of love; the natural and the mental, which can also be called the rational, or the elective. Natural love signifies more of an instinctual love to move toward what is good and ultimately, toward God. Rational, or mental love is that which is based in free will and is based on choice rather than instinct.

Natural love is of the end, for all things, all creatures, are inclined by their nature toward their proper place, their finis or goal. Natural love is the desire each creature has for its own perfection; in angels and men, it is love for the supreme good, which is God…Elective love can err, since it involves choice, as natural love does not. Only those creatures that have free will can have elective love, hence this love is given only to angels and men…Natural love is of the end, but elective love is of the means to the end.15

Where natural, instinctive love cannot err, in this conception, rational love can err, and Virgil outlines three ways in which it may do so. First, by choosing the wrong goal or loving what is evil, secondly, by loving something that is good, but inordinately (think of the excess of gluttony) or third, by loving something that is good but not strongly enough to “satisfy the call of duty” (85-86), which would fall under sloth.

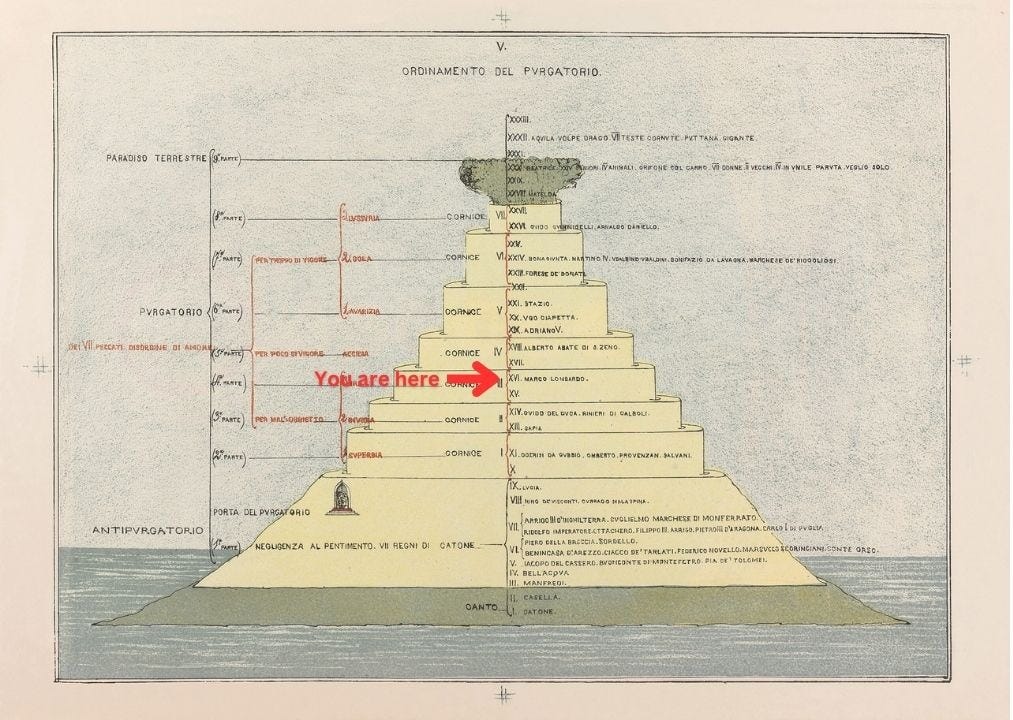

The three forms of erring elective love are purged on the seven terraces of Purgatory, as will be explained: love of an evil object (apprehended as good) on the first three, lower terraces; a love of the good which is not vigorous enough (sloth), on this central terrace; and excessive love of a secondary good on the three upper terraces. The purgatorial system is thus tripartite, even as the punitive system of Hell is.16

As Virgil continued to explain, when this rational love is fixed on virtue and is temperate in its love of worldly goods—secondary objects which are directed toward good, but which are not God—then they are not in error. But when rational love falls under one of those three errors and begins using love in the wrong capacity, then it goes against its given purpose.

From this you see that—of necessity—

love is the seed in you of every virtue

and of all acts deserving punishment.

xvii.103-105

How beautiful is this sentiment, that love is the seed of everything, and how much more power does love hold when directed toward the good. To temper the desires to aim toward the good is then the greatest of all possible uses of free will. And yet even actions that end in error began with a love for something, just directed away from that aim toward goodness. We saw that clearly in Hell, with all the characters that were fulfilled in obtaining exactly what they wanted for eternity. Love is not just ‘a’ function of the will, but ‘the’ function of the will.

Now, since love never turns aside its eyes

from the well-being of its subject, things

are surely free from hatred of themselves;

and since no being can be seen as self-

existing and divorced from the First Being,

each creature is cut off from hating Him.

Thus, if I have distinguished properly,

ill love must mean to wish one’s neighbor ill;

and this love’s born in three ways in your clay.

xvii.106-114

Here Virgil defines some more subtleties; first, that one cannot actually hate or do evil to oneself;

No man wills and works evil to himself, except he apprehend it under the aspect of good. For even they who kill themselves apprehend death itself as a good, considered as putting an end to some unhappiness or pain.17

Nor, he said, could anyone truly hate the source of their own being in God:

No love can, fundamentally, hate that which loves; it cannot hate itself, nor since the creature’s self-existence depends on and lives by the Creator, can any creaturely love hate that Creator. This must certainly be set against those circles of the Inferno in which the damned seem to hate both God and themselves, but a) Virgil is speaking of natural and not final supernatural state; and b) it is the rational choice of which he is talking, and in hell the rational choice no longer exists; there are ‘the people who have lost the good of intellect’-choice has been swallowed up in desire.18

If Virgil had made his case thoroughly, it proved his point that any error that drove an action must be toward something other than self or God, and the result was that they were acting against neighbor, or external factors, and as we look at the sins being purged in lower Purgatory, they have all fit into this category; after defining these subtleties of love and the key to all action, Virgil began to apply this to the levels of Purgatory.

He pointed to the sin of Pride which we found in the first terrace, the “intolerance of any rivalry,”19 then to the second terrace of Envy, the “fear of loss through competition,”20 and finally of Wrath in the third terrace, the “love of revenge for injury.”21

This “threefold love” are then the sins that are purged on the lower three levels, representing the love of choosing the wrong goal. (Note here, reader, that lines 124-125 signify the exact center of our journey through the Comedy). These sins are closest to Hell through being at the bottom, and as we climb higher, the sins become less intense, just as the sins in the upper levels of Hell were simpler than those in the deeper pit. Next, Virgil moves to “love that seeks the good distortedly” (126), indicating too much or too little zeal.

Each apprehends confusedly a Good

in which the mind may rest, and longs for It;

and, thus, all strive to reach that Good; but if

the love that urges you to know It or

to reach that Good is lax, this terrace, after

a just repentance, punishes for that.

xvii.127-132

This is Sloth, the center of Purgatory; with three terraces below it and three above it, the fourth terrace of Sloth stood alone in its sluggish and lax nature, standing still when it should be moving.

Three stages in love, as will be explained in the next canto, are represented in this tercet: perception, desire of the object, and attainment of the object.22

Virgil then touched on the terraces above Sloth, those of excess; Avarice, Greed, and Lust, those that strive toward joy but cannot be fulfilled.

There is a different good, which does not make

men glad; it is not happiness, is not

true essence, fruit and root of every good.

The love that—profligately—yields to that

is wept on in three terraces above us;

but I’ll not say what three shapes that love takes—

May you seek those distinctions for yourself.

xvii.133-139

Virgil’s speech, as if ending in media res, will continue into canto xviii.

💭 Philosophical Exercises

Love is energy of life.

~ Robert Browning

I. The Cradle Above the Abyss

The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.23 In this brief crack of light we call life, the most meaningful tool we possess is our faculty of attention. What posterity may one day say about us, after we cross the threshold of postnatal abyss, will depend on what we chose to pay attention to while we were able to breathe.

Our attention is like a narrow beam of light cutting through the darkness of the world around us. What we see, what becomes real to us, depends entirely on how we choose to direct that beam.

II. How to avoid a misbalanced life?

In this section of Philosophical Exercises I would love to draw the beam of your attention to the fact that we have crossed another invisible threshold hidden in plain sight. In fact, one may say, that we have truly escaped Inferno somewhere at this point.

The abyss of Inferno rests on two opposing principles: misura and dismisura (measure and excess). This echoes the Aristotelian idea that a good life is a life of balance.

Take the example of a soldier. To be truly brave is not simply to charge into danger, but to stand precisely between two extremes: recklessness and cowardice. A brave soldier is one who knows when to act boldly and when to hold back, who can be reckless at the right moment and cautious at the right moment.

For caution in the face of necessary risk is not wisdom, but cowardice. And recklessness in the wrong moment is not courage, but folly.

This is why, among the first souls we encounter in Inferno, are the avaricious and the prodigal—those who hoarded and those who squandered. Generosity, in the Aristotelian sense, is the virtue that lies between these two extremes.

It’s also one of the reasons why Inferno is built upon the principle of contrapasso, a punishment by symbolic contrast or mirror image. The damned suffer not just for their sins, but through the opposite excess. Their lives were so deeply disordered, so imbalanced, that even Hell cannot restore harmony.

The scales remain tipped, eternally. Or, to better use a Russian saying: the grave will correct the hunchback. Only Inferno can correct and tip the scales back for some people.

III. The Architecture of Purgatorio

The architecture of Purgatorio is different; as we’ve discussed before it’s marked not by despair, but by purification, by hope, by songs and prayers that rise like incense toward the heavens.

As Dante and Virgil leave the terrace of the wrathful, Dante asks his guide what lies ahead. In response, Virgil offers more than a simple answer, he touches on a broader idea. Much like in Canto XI of Inferno, he explains to the pilgrim the moral architecture of Purgatorio itself.

This is where we come back to our beam of light, to our cradle that rocks above the abyss, for one of the subjects that I am intensely curious about is the nature of our attention, or in Dante’s view: Love.

We are driven by love, but our love can be misplaced, as our attention could be pointed in the wrong direction, so our love can be misplaced on wrong things. Our minds are still fresh with images of the envious, of Sapia in particular, who placed her object of love on the earthly things and therefore wanted the destruction of her own countrymen. This comes from excessive self-love as well, but I am getting ahead of myself.

IV. Your Attention is What You Love

I’ve been collecting different ideas and reflections on the nature of attention. One struggle I’ve always had with the word attention is that it seems passive, almost mechanical, neutral. Like a torchlight used during a blackout, attention illuminates, yes, but it doesn’t guide itself. The torch doesn’t decide where to shine, it is the person holding it who does.

When I’ve written about attention in the past, I always felt something was missing. What exactly guides that beam? What makes us focus on one thing rather than another?

Imagine getting lost in a forest at night with only a torch in your hand. Your first instinct would be to find the way out. You would use the light to search for a path. But if you suddenly heard a sound in the distance, you might instinctively shift the beam to investigate, perhaps out of fear, desire not to be eaten, or simple caution. Still, it wouldn’t be the torch making that decision. You decide where to look.

And so it is with our attention. The torch is neutral. It simply reveals what it’s pointed toward. What truly matters is who holds it and why.

This is the marvellous revelation of Dante to my understanding of attention. Attention is the torch and Love is us. Attention may be the beam of light, but it is love that guides the hand.

V. Misplaced Love

Let’s stretch our imagination once more; it is worth mentioning that imagination, in its various forms, is one of the key words of this canto and that of the last.

Let’s return to the dark forest, where all you have is a single torch to guide your way. Naturally, your instinct would be to find the path out. But if your mind is cluttered, if you are unfamiliar with the terrain, the nature of the forest, its hidden paths, its creatures, you’re in real danger.

You might misplace the beam of your torch, following the wrong trail. When hunger sets in, lacking knowledge of which berries are safe, you might eat the ones that poison you. You might choose a path that leads you deeper into the woods rather than out of them.

In such a case, the torch (your attention) can become your enemy. Misguided light can be more dangerous than darkness. At least in the dark, you might have stayed still. Sometimes, it would have been safer not to move at all.

In Inferno, we had to learn how not to fall into misbalance. We had to train ourselves to walk evenly, so we wouldn’t grow too weary. We had to learn which berries were safe to eat, and how to recognise the ones that were deceptively sweet but poisonous.

Most of all, we had to learn not to despair, even in the terrifying situation of finding ourselves lost in the dark forest. (Remember the circle of suicides?)

In Purgatorio, we still have to refine many of the lessons we began to learn in Inferno. But there is a crucial difference: here, we are not only learning how to purify ourselves, but also how to draw closer to the right path and to orient ourselves toward the light.

Virgil explains that there are two kinds of love: 1) Amore Naturale, which cannot err since its instinctual or planted by God (self-preservation, desire for good) 2) Amore D’animo - which is guided by our reason and our will24.

The second kind of Love can go terrifyingly wrong in three ways: a) Love directed at wrong object (Prideful and Envious) b) Disordered Love - this is love for good things but in chaotic and disordered manner ( gluttony, lust, greed or avarice) c) and, finally, Acedia or too little desire for true good (exemplified by sloth which we are going to cross in the next terrace).

In this view every sin is Love gone astray, either by placing its focus on the wrong object (and subject); by its intensity; or priority.

To return to our imaginative forest, in which we find ourselves lost with a group of companions: a completely misdirected form of love would be, for instance, feeling envious of your companions’ skills; being too slothful to make any attempt to find the path out; or prioritising minor obsessions (such as cooking a delicious meal25) over the most important task, which is to find the way out.

VI. Philosophical Exercises

This vision opened a whole new perspective on how I study the nature of our attention. It, in fact, changed the way I live.

Before, I studied the torch, I disassembled its parts and looked how it works from inside, how many batteries it requires, what are its settings and wires that connect it to each other. But with the concept of Love, a new perspective had opened.

There are many goods in life, am I shining the torch of my attention to the most important one? Am I doing it with the correct intensity? What are the things that I should not place the beam of my light at all?

The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us, that what we loved in life will determine how our life will be defined.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. Haman, Lavinia and Procne

We haven’t even touched on the powerful visions Dante experiences in this canto, the Crucifixion of Haman, Procne’s murder of her own son, and Lavinia’s grief. Each serves as a warning of what wrath can do to us when left unchecked.

Haman is crucified on the very gallows he built for his enemy. Procne, in a fury of vengeance, kills her own son after discovering that her husband, Tereus, raped her sister. Lavinia, though more symbolic than active, stands as a voice of mourning — rebuking her mother Amata, whose unchecked rage led to suicide and the abandonment of her daughter.

Once again, Dante presents us with a moral structure: not just virtues to imitate, but passions to transfigure. We are shown what love becomes when it flames out into cruelty, vengeance, or despair and how the soul must learn to act without destroying, to feel without falling.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

“This spirit is divine; and though unasked,

he would conduct us to the upward path;

he hides himself with that same light he sheds.~55-57

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on Purgatorio 378

Singleton 378-379

We were introduced to her story in Purgatorio ix.15 in reference to the melancholy swallow.

Singleton 182, also see Ovid Metamorphoses vi. 590-977

Esther 1:1

Singleton 381

Thomas Aquinas Summa Theologica II-II, q. 158 a. 2

See Purgatorio vii.44-60

Singleton 389

Singleton 390

Paul A. Camacho, “Educating Desire: Conversion and Ascent in Dante’s Purgatorio” 1

Thomas Aquinas Summa Theologica I q. 63 a. 2

Thomas Aquinas Summa Theologica I-II, q. 28 a. 6

Allen Mandelbaum, The Divine Comedy 668

Singleton 392, 394

Singleton 395

Thomas Aquinas Summa Theologica I-II, q. 29 a. 4

Charles Williams, The Figure of Beatrice 163

Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory 204

Sayers ibid

Sayers ibid

Singleton 406

The most powerful opening lines I’ve ever read, this comes from Vladimir Nabokov’s Memoir ‘Speak, Memory’

I doubt my reader would have skipped the previous canto and went straight to this one, but there is an important aspect of the free-will that is worth having a look if you hadn’t yet done so.

One must eat, eat in the right measure, nothing wrong with this, but if you’re not even hungry, to prioritise food when you’re lost in forest full of predators is ridiculous. Apologies for primitive metaphors!

"In this brief crack of light we call life, the most meaningful tool we possess is our faculty of attention." This feels so important to me. There are more days behind me than in front of me at this point. I have tried to do good, but how do I know if I succeeded. This attention guided by love could be the key. A bit of clarity in a complicated world. Thank you Vashik.