How to Avoid Becoming a Bystander in Your Own Life

(Inferno, Canto XXX): On Semele, Hecuba, and the Shame of Watching Souls Rot

“No evil dooms us hopelessly except the evil we love, and desire to continue in, and make no effort to escape from.”

~ George Eliot

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

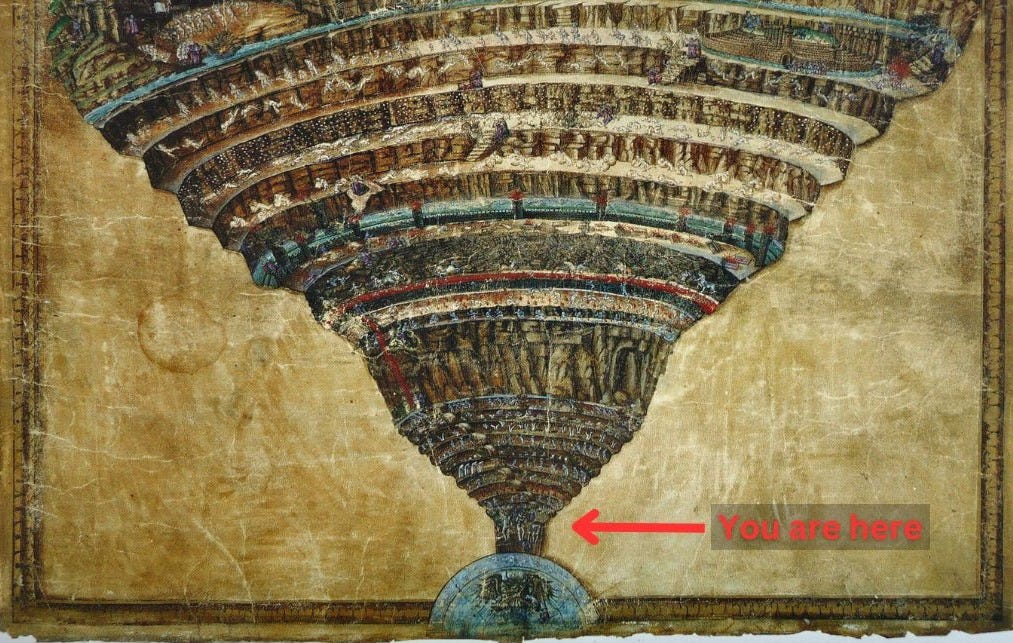

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Thirtieth Canto we are still in the tenth and last bolgia of the Eighth Circle with the Falsifiers. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Eighth Circle, tenth bolgia continued - Falsifiers of persons suffering madness - Gianni Schicchi and Myrrha - Falsifiers of coin suffering dropsy - Master Adamo - Falsifiers of words stricken with fever - Potiphar’s wife and Sinon - Virgil rebukes Dante for his interest in verbal wrangling - Dante’s shame.

Canto XXX Summary:

Dante’s exploration of the tenth bolgia of the Falsifiers continues with two stories of extreme madness that in mortal terms, go past the edge of that sanity that keeps us human.

First is King Athamas, who, under a curse from Juno, was driven to insanity. Thinking in his delusion that his wife and their two children were a lioness with her cubs, he took hold of his own son Learchus, dashing him to his death. Ino, in her desperation, and holding their other child Melicertes, threw herself into the sea to escape.

This madness of Athamas was caused by the rage of Juno against the mortal Semele, who was with child by Juno’s husband Jupiter. Not only did Juno punish Semele, but also sought revenge on Semele’s family. Athamas was married to Semele’s sister Ino.

Juno visited Semele disguised as an old nurse, giving advice about her divine lover Jove. She told Semele to make Jupiter prove his love by appearing to her as he would to Juno, knowing what the result would be. Semele asks Jupiter for a gift and he hastily promises her anything. She asks to see his true form, and he cannot refuse his oath:

Instead, he picks a bolt the Cyclops forged,

One with reduced anger and a lower flame

(they call such weapons his Light Artillery);

And so appareled, came to Semele;

But she, whose mortal body could not bear

Such heavenly excitement, burst into flames

And was incinerated by Jove’s gift.

Ovid Metamorphoses III.393-399

The madness and death caused by Juno’s rage are extreme, but there is more to come. The Trojan War, the epic battle between the Greeks and the Trojans as told in the Iliad, brought the house of Priam to the lowest of the low as the wheel of Fortune turned:

Ill Fortune, on the other hand, when she

Upsets men’s high estate and tumbles them

Low in the mire from off her turning wheel,

And like a stepdame lays upon their hearts

A painful poultice, spent and thin, not strong

With vinegar, this teaches them the truth

That none should boast they’re Fortune’s favorites.

de Lorris & de Meung, Roman de la Rose 24.33-39

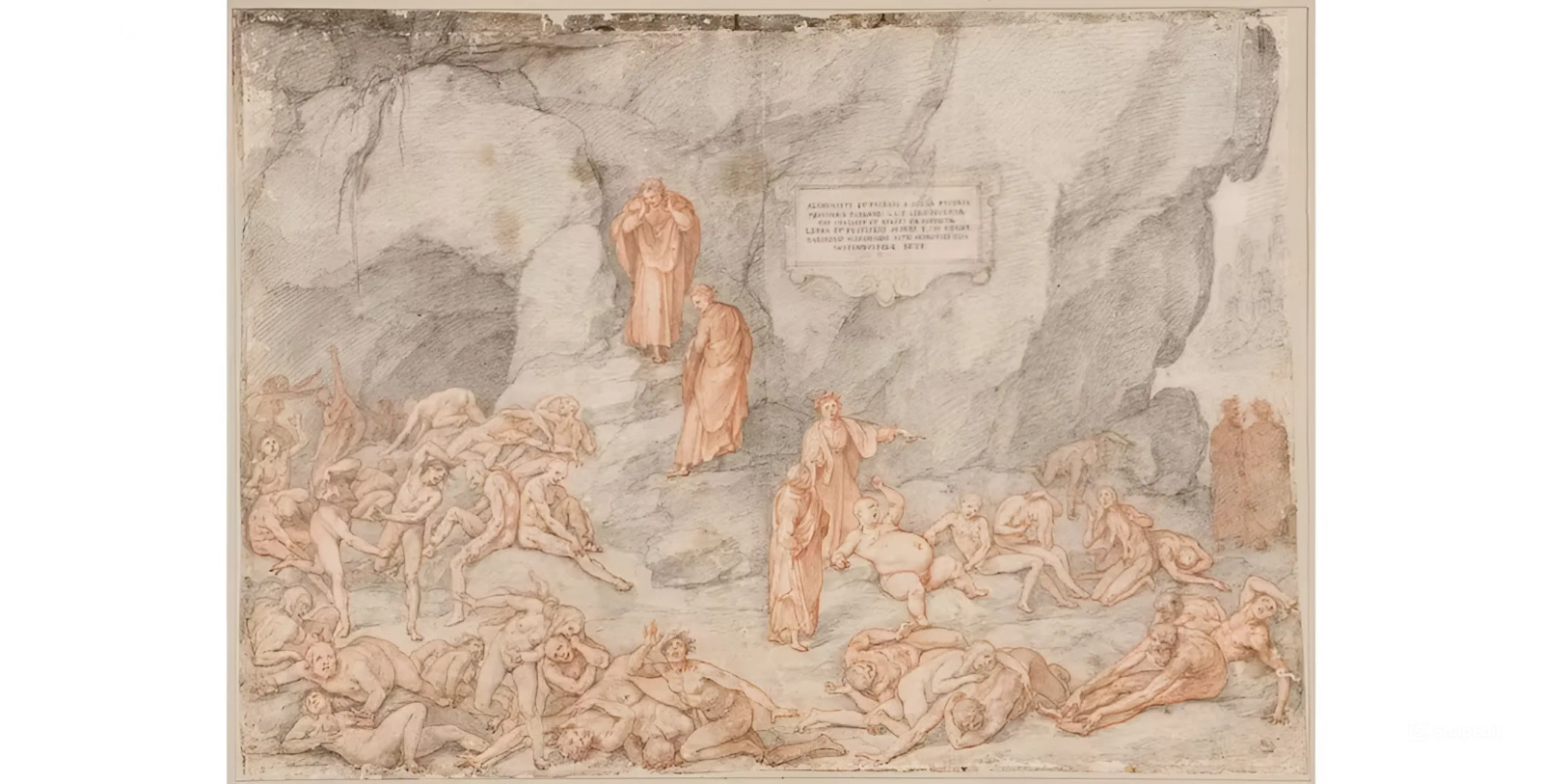

This ill fortune led to the terrible suffering and madness of Hecuba, wife to King Priam. She watched him be slain an ignoble death on the altar of their household gods, aged, trying to fight his last feeble battle. Hecuba and Polyxena, one of her many daughters, were captured by Greek soldiers, and Polyxena was sacrificed on the tomb of Achilles — as his ghost commanded — by his son Pyrrhus.

Stricken with grief, she then found her son Polydorous washed ashore by the sea, slain and thrown into the waters by the king Polymestor, he who was asked to be Polydorous’ guardian by Priam. In revenge, Hecuba plucked out the eyes of Polymestor, and this was the moment her grief turned her mind to madness:

The Thracians were enraged by this disaster

Which befell their king, and started to throw stones

And spears at Hecuba; growling, she snapped

At the stones they threw at her, and even though

Her jaws were meant for words, she started barking

When she attempted speech. Because of this,

The place has taken (and still takes) its name

In Greek, Cynossema: Sign of the Dog,

From the place where Hecuba, remembering

The evils of that distant time, would howl

Across the Thracian grasslands mournfully.

Ovid Metamorphoses XIII.819-829

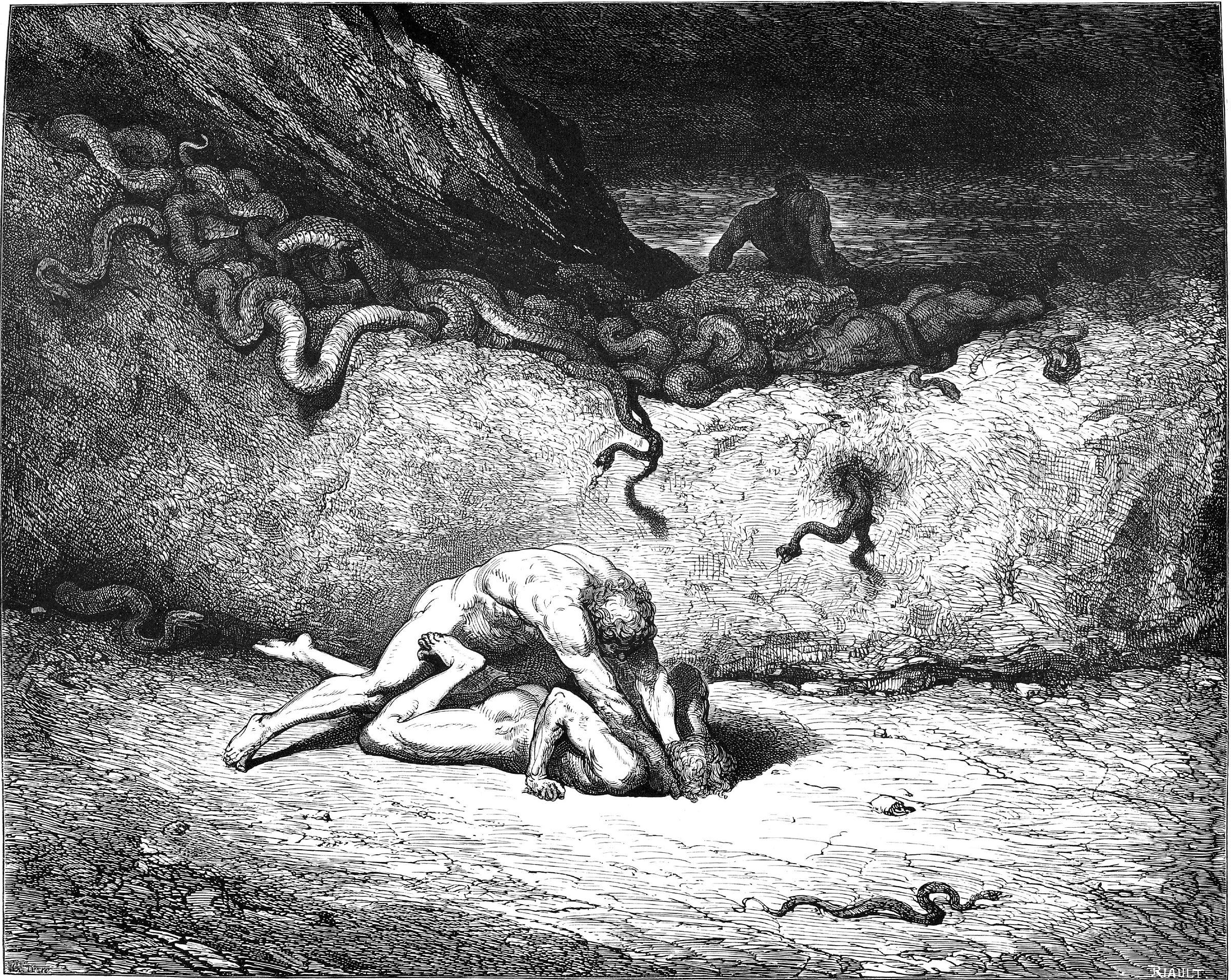

These insanities, which are so extreme, are as nothing to what Dante sees in the tenth bolgia of the Eighth Circle of Hell. Two mad and running shades run toward him:

But neither fury—Theban, Trojan—ever

was seen to be so cruel against another,

in rending beasts and even human limbs

as were two shades I saw, both pale and naked,

who, biting, ran berserk in just the way

a hog does when it’s let loose from its sty.

XXX.22-27

These two shades were as the Furies of myth in their madness. One sinks its teeth into Capocchio the alchemists neck, a vivid reminder of the corporality of the shades in these deepest reaches of Hell. Capocchio is dragged away, while Dante’s companion from the end of Canto XXIX, Griffolino, the swindler who tried to show Alberto da Siena how to fly - points out the biting shade as Gianni Schicchi, one who falsified persons, an imposter.

Gianni Schicchi posed as Buoso Donati, father of Simone Donati — the fact of his recent decease hidden so they could work their plan — in order to write a will in favor of Simone. The favors that Gianni gave to himself while dictating the new “will” were plenty. In the account of the dictation of the will, Gianni leaves himself 500 florins, which he insists Buoso is happy to leave him (at the protests of the son, Simone, for whom he is doing this), as well as his finest mule — the “lady of the herd” from line 42— again insisting again that Buoso would want Gianni to have it.

Dante prays the second mad shade will not bite Griffolino as Gianni bit Capocchio. Dante inquires about that second shade, and Griffolino points her out as Myrrha, consigned to hell not because of her disordered passion, but for concealing her identity — hence the impersonation — so as to fulfill the object of that desire.

Myrrha, seized with an unholy passion for her own father, came to him disguised, with the help of her nurse, and committed the unspeakable act of sexual relations with him. Upon her father’s horrified discovery of what he had done, she fled as he tried to kill her. In Ovid’s account she is transformed into a tree where her child grows within her, and the baby Adonis is born from the tree trunk of her body, which weeps tears of myrrh. The full story, in vivid detail, is told in Ovids Metamorphoses X.372-617.

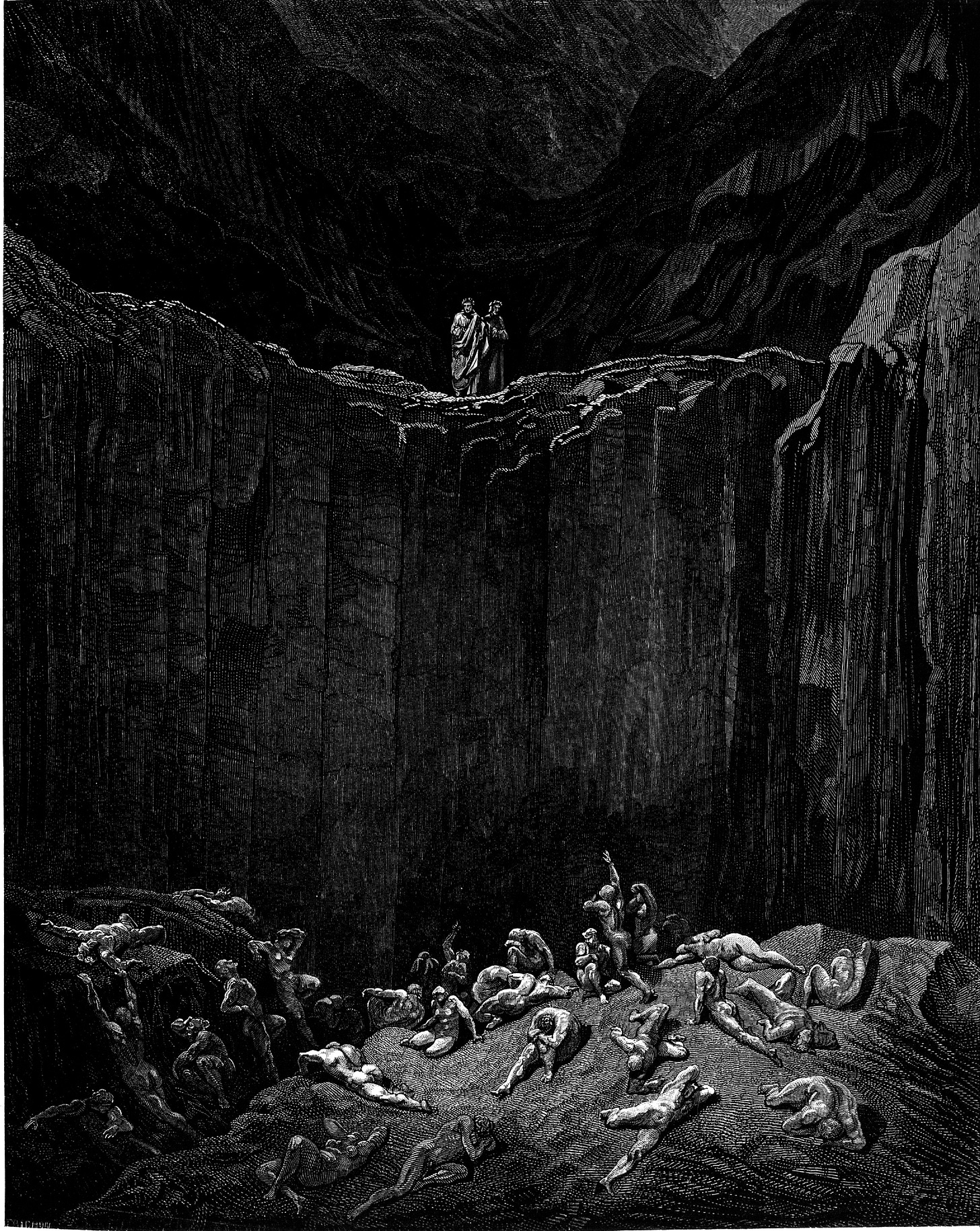

Gianni and Myrrha had run on, and Dante turns to see the shade of Master Adamo, striking in his resemblance to a lute, as his torso is swollen and distended with the shape of the wide bottom of his belly tapering off to the top, where his head is so much smaller than his body, which is swollen by dropsy.

This imbalance of the four humors of ancient medical diagnosis were the root of dropsy in medieval medicine, the basis of which stretched back to Greek medicine in antiquity. The humors of the body were black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm, which needed to be balanced to create health.

When someone with dropsy eats and drinks more and more, those humors are corrupted and convert themselves into bad phlegmatic humors. And therefor the more he eats and drinks, the more the illness grows and swells, and he becomes thirstier.1

With his visage of parched thirst, Adamo had the look of consumption as well as dropsy. He spoke to Dante with a note of sarcasm as to his corporeal state that was not consigned to Hell. While Adamo once had everything he could desire on earth, in Hell, his craving has been reduced to a single drop of water, reminiscent of the parable of the rich man and Lazarus in Luke 16:23-24. He dreams and imagines water, the sweet landscape he knew on earth, the sighs of longing escaping him:

The rivulets that fall into the Arno

down from the green hills of the Casentino

with channels cool and moist, are constantly

before me; I am racked by memory-

the image of their flow parches me more

than the disease that robs my face of flesh.

XXX.64-69

In this sweet landscape, he can see Romena, the place that he learned his false art. The florin, the coin of Dante’s day, was stamped on one side with a lily and on the other with the patron saint of Florence, John the Baptist, and was made of 24-carat gold. Adamo had mixed an alloy into that gold, reducing it from 24 carats to 21 carats. For this crime against the state, Adamo was burned at the stake.

He longs to see those who commissioned him to do the forgery: the brothers Guido da Romena, Alessandro, and for the third, one of the two remaining brothers of the Conti Guidi family, either Aghinolfo or Ildebrandino. He would trade the precious site of the fountain of Branda and it’s abundant water to see these brothers in Hell with him, whom he blames for his misfortune.

But could I see the miserable souls

of Guido, Alessandro, or their brother,

I’d not give up the sight for Fonte Branda.

And one of them is in this moat already,

if what the angry shades report is true.

What use is that to me whose limbs are tied?

XXX.76-81

Guido is there already, as Adamo has heard from the mad and running shades who see much more of the tenth bolgia than Adamo will ever see at the rate he can move his swollen body: one inch in one hundred years.

Porena has calculated that it would take Master Adam seven hundred thousand years to make his way around the whole circle of the bolgia-yet it should be remembered that he has all eternity before him!2

Dante’s measurements of the tenth bolgia being at least “half a mile across” seem fantastic when looking at the bigger scope of the Eighth Circle and all of it’s ten trenches; consider the size of the bridge that would be needed to cross each bolgia. Here, the measurements may be more symbolic for the vastness of the region than exact measurements.

Two more sinners catch Dante’s attention, steaming with the heat of their fevers. If Adamo moves slowly, then these shades are even slower; he has never seen them move since his arrival. They are the falsifiers of words: perjurers and liars.

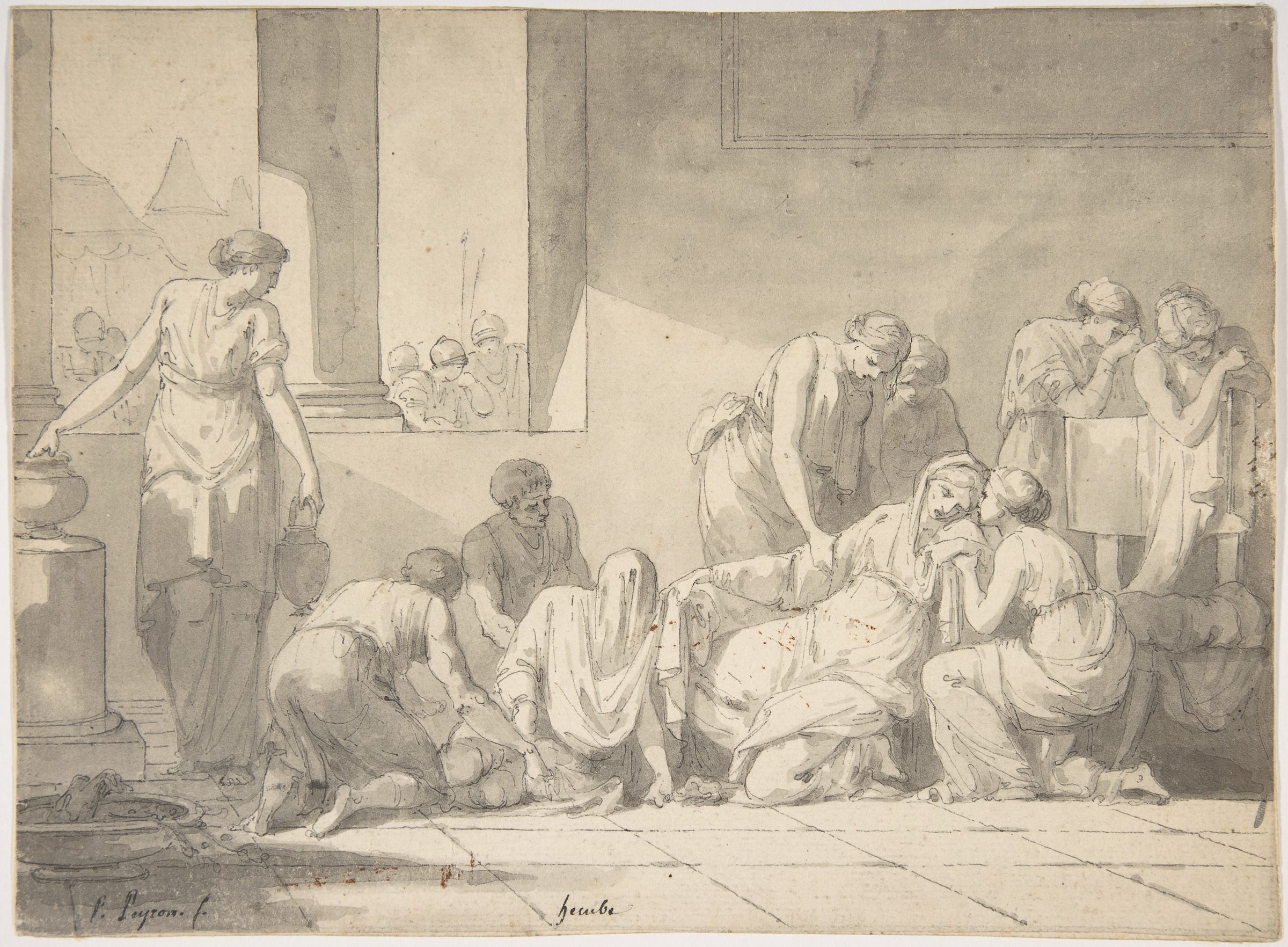

The first, “the lying woman who blamed Joseph” (XXX.97) is the wife of Potiphar, a captain of the Pharaohs guard in Egypt when Joseph (of the robe of many colors) was moving his way from being a slave to being a trusted servant in the household in the book of Genesis. Potiphar’s wife — she is never named — attempted to seduce him, but in his uprightness he rejected her; running away from the encounter, he left his coat behind, which she used as proof that he had tried to seduce her. Joseph was cast into prison.

And she caught him by his garment, saying, Lie with me: and he left his garment in her hand, and fled, and got him out. And it came to pass, when she saw that he had left his garment in her hand, and was fled forth, that she called unto the men of her house, and spake unto them, saying, See, he hath brought in an Hebrew unto us to mock us; he came in unto me to lie with me, and I cried with a loud voice: And it came to pass, when he heard that I lifted up my voice and cried, that he left his garment with me, and fled, and got him out. And she laid up his garment by her, until his lord came home. Genesis 39:12-16

The second of the falsifiers of words is Sinon of the Trojan War, the Greek warrior who defected to the Trojan side, swearing his loyalty to them and his disdain for the Greeks. His malicious intentions however were to convince the Trojans to bring the gift horse within its gates, so that the Greek warriors hidden inside could come out during the night and raid from within the city walls. That was the turning point of the battle, which the Greeks then won.

Meanwhile, observe, some Dardanian shepherds are dragging a young man,

Hands tied behind him, straight to the king, with a great deal of shouting.

They didn’t know him. The youth had approached them himself to surrender

Willingly, and with a purpose: to open up Troy to Achaeans.

Trusting his own courage, he was prepared for both possible outcomes:

Either he’d pull off his treacherous ruse or he’d die, that was certain.

Aeneid II.57-62

Sinon, offended by Adamo’s words, struck the distended belly which resounded like a drum, for which Adamo struck Sinon in the face, receiving the taunt

“Although I cannot move

my limbs because they are too heavy, I

still have an arm that’s free to serve that need.”

And he replied: “But when you went to burning,

your arm was not as quick as it was now;

though when you coined, it was quick and more”

XXX.106-111

Here begins an almost humorous back and forth between Adamo, the coiner, and Sinon, the liar, each hurling insults and blame at the other. Their words grow more and more insulting, trying to pin the other as the greater sinner, ending with Adamo claiming that his thirst at least only swells his great body, where Sinon is burning and ready to split with the dry fever in his head, taunting that “few words would be sufficient invitation / to have you lick the mirror of Narcissus.” (XXX.129)

Narcissus, in his scorn for the feelings of the enamored nymph Echo, was punished by the goddess Nemesis to fall in love with himself as much as others had fallen in love with him, but with no fulfillment. He was so taken with his own reflection in the “mirror” of the pool of water, that he wasted away and died, leaving the flower named after him in his place:

Worn out and overheated from the chase,

Here comes the boy, attracted to this pool

As to its setting, and reclines beside it.

And as he strives to satisfy one thirst,

Another is born; drinking, he’s overcome

By the beauty of the image that he sees;

He falls in love with an immaterial hope,

A shadow that he wrongly takes for substance.

Ovid Metamorphoses III.530-537

Dante has been so engrossed in this volley of sharp words that Virgil’s admonition to him brings him instantly to shame;

Even as one who dreams that he is harmed

and, dreaming, wishes he were dreaming, thus

desiring that which is, as if it were not,

so I became within my speechlessness:

I wanted to excuse myself and did

excuse myself, although I knew it not.

XXX.136-141

Virgil knows Dante both inside and out, and the depth of his shame cannot be hidden from his guide. Dante’s shame shows the remorse unknown to those shades in Hell, and the depth of that shame has already washed away any stain from his error, indeed would wash even a greater stain away.

Virgil assures him, that should he be so tempted to listen to such base speech again, his presence will be there to keep Dante from falling, sliding, into the love of slanderous speech.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

“Who looks outside, dreams; who looks inside, awakes.”

~ Carl Jung

The role of a guide is to provide and preserve direction for their companions. A great journey brings joy, but that very joy can also beguile us, tempting us to lose sight of the destination.

For this reason, as a guide to myself, I must remind myself that the aim of the Philosophical Exercises is to extract the nourishing nectar from Dante’s verses. For Dante’s journey served as an instruction to him, just as it serves as a path of escape and illumination for us.

So, what does Dante unveil to us here?

One lesson could be that the worst one can do is to become a bystander to his or her own life, which we discovered from Virgil himself at the end of this canto, but first, to understand this deeply and fully, we must explore different kinds of madness…

I. Distinguishing Madness from Madness

‘Choose wrong’ - writes Tom Holland in his Persian Fire - ‘and the path of the Lie, and of Chaos, would be opened; choose right, and the path of order, tranquility and hope will unveil.’3

There exists a realm governed by immortal gods (or God), and there is a realm reserved for us mortals. Chaos and destruction follow the cities, and the souls, that dare to transgress the boundary between the two. Annihilation and suffering await those mortals who believe they can equal the divine.

For this is the story of Semele…

Semele was seduced by Juno - goddess of nature, known to the Greeks as Hera - into believing that she could behold Jupiter (or Zeus), the king of all gods, in his full divine glory. It was a deception carefully designed, for no mortal could endure such a vision.

Juno tricked Semele into demanding this impossible revelation, and Jupiter, bound by his oath, granted her wish. In an instant, Semele was incinerated by the sheer radiance of the divine and vanished into the shadows of Hades.

From this fatal union, however, was born Dionysus - the god of ecstasy, madness, and divine intoxication.

I have to say that the Greeks were masters of the psyche; this is why their myths continue to be so revealing and intoxicating for centuries.

Why does Dante bring up this myth in this canto?

My attentive reader may have already sensed the reasons, but allow me to restate them. Juno, in mythology, represents Nature. Semele, a mortal from the once-mighty kingdom of Thebes, is seduced - by Juno’s subtle influence - into believing she can endure the full presence of the divine, that she can rise to the level of the Most High, if only she dares.

It is the classic temptation: once the human mind believes it has conquered Nature, it begins to see itself as godlike, limitless. (Does this remind you of anything that is happening in our time?) This myth, retold by Dante, warns us of the spiritual arrogance born from intellectual pride - pride that seeks to rival the divine, not in harmony, but in defiance.

Mortals cannot be equal to God. Every attempt of it is a falsification, and every falsification leads to insanity. This is why the “marriage” between Semele and Zeus produces no one else but Dionysius (Bacchus) - the god of divine intoxication and madness.

II. Hecuba: Madness out Despair

Hecuba was the wife of the Trojan king Priam. After the fall of Troy, she was taken captive by the Greeks and brought to Thrace, where she witnessed the sacrifice of her daughter Polyxena on the tomb of Achilles. In the depths of her grief, she wandered to the shore, only to find the body of her son Polydorus washed up by the sea.

The unbearable weight of witnessing her children’s deaths shattered her mind. Overcome by madness, her voice turned to barking, like that of a dog. In a fit of fury, she murdered Polymestor, the king of Thrace, and, as Ovid recounts in the Metamorphoses, tore out his eyes with her own hands. It was a just revenge, for it was Polymnestor who killed Hecuba’s son.

The natures of these two mythological characters - that of Semele and Hecuba - are stark. For during the war, Hecuba (as it is depicted in the Canova’s plaster on top of this section) offered sacrifices and prayers to goddess Athena to protect her city. She respected the gods and never dared to act like Semele.

Thus Hecuba’s madness is driven by her tragic fate, while Semele’s doom is caused by her divine transgression.

III. Philosophical Exercise: Four kinds of Falsifiers

In the previous canto, we met the first kind of falsifiers - alchemists - those who believe they can alter the laws of nature by using the powers of science. Each group of falsifiers suffers from a particular kind of illness. As you might remember, alchemists were tortured by the relentless leprosy. So, in this canto we meet:

Impersonators, who suffer from hydrophobia.

Counterfeiters of coin, they suffer from dropsy

and, Perjurers, who are feverish

The affliction of the counterfeiters is one of the most vivid examples of contrapasso: those tormented by dropsy are unable to expel the water from their bodies, and yet they remain consumed by an unquenchable thirst.

These are the four kinds of rotting souls whose corruption brings destruction - not just upon themselves, but upon entire individuals, populations, and nations. To paraphrase Tom Holland’s powerful words that we encountered before: these are those who choose wrongly, who prefer the path of the Lie—a path that inevitably leads to chaos and collapse.

I want to remind us all that these are the damned that are the closest to the Satan himself. Why?

I believe that if we look closely at each of these sinners, we will find that they carry within themselves the features of all the previous bolgias. Like a Russian doll enclosing smaller versions of itself, each layered within the next, these four falsifiers are an amalgam - an embodiment - of all ten bolgias we have traversed so far.

Alchemists falsify knowledge. Impersonators falsify love and identity. Counterfeiters corrupt the material elements themselves. Perjurers distort the very authenticity of words and speech.

These four horsemen differ from their apocalyptic counterparts. The latter - war, famine, conquest, and death - are often beyond our control. War can strike even those who long for peace; famine may follow drought regardless of one’s virtue.

The Four Horsemen of Fraud, however, are entirely self-inflicted and self-destructive.

This is why Dante places them here. In the Inferno, no one is damned for what they could not choose. Sinners like Master Adam made their choices freely - and so they suffer according to the laws of the Divine justice.

IV. Philosophical Exercise Pt. II: Don’t be a bystander in your own life

I was intent on listening to them

when this was what my master said: “If you

insist on looking more, I’ll quarrel with you!”And when I heard him speak so angrily,

I turned around to him with shame so great

that it still stirs within my memory.

Don’t we all deserve - yes, you and I - a similar kind of rebuke?

Aren’t we, in this age of unrelenting screens and restless scrolling, afflicted by a modern strain of voyeurism?

Both Virgil and Dante remain strikingly silent throughout this canto - indeed, it is the quietest moment for Virgil in all of Inferno so far. Our guide, our reason, appears almost asleep as we watch the rotten souls bicker, slap, and claw at one another.

And don’t we witness the same spectacle today? Rotten souls locked in endless quarrel across politics, celebrity culture, and even the so-called intellectual arenas. The louder the noise, the more reason retreats into silence.

Why do we poison our minds and lower our souls to the levels of these beasts by paying attention to them? Why do we prefer the company of rotters in tavern over the company of saints in church?

We are what we think. We are what we pay attention to. This is why Dante feels ashamed when Virgil reprimands him for being so engrossed into the dirty quarrels of the damned.

For a moment it felt as if Dante had annulled the entirety of his hard work and effort by surrendering his attention to watching the damned.

Virgil rebukes him, and it is thanks to him that Dante is awoken from his slumber, but dear reader, remember that Virgil himself was quiet here. Our reason can easily be lulled by seductive entertainment.

If there is a philosophical lesson I personally draw from this canto, it is this: when we watch rotters quarrel, we become bystanders to our own life, mere spectators. We pause our journey, just as Dante does here, suspended in observation rather than progress. It’s as if we return, momentarily, to the dark forest we thought we had left behind.

And that is the danger. We should be careful. Our own reason, like Virgil here, might be too weary or too quiet to awaken us, to remind us of our path, and to pull us back into awareness before we become too entangled in the noise.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

The inversion of musicality

I saw one who’d be fashioned like a lute

if he had only had his groin cut off

from that part of his body where it forks.

In Dante’s time, string instruments like the lute were thought to possess a divine and harmonious quality, their melodies seen as echoes of celestial music. In contrast, drums—purely percussive, grounded in rhythm—were associated with the primitive and the earthly. Yet here, in this grotesque corner of the Inferno, we witness a perverse musical inversion: the lute, once a symbol of refined beauty, now mimics the crude thudding of a drum. It is as though even harmony itself has been corrupted, its noble voice reduced to a hollow, mocking beat.

False accusation: Potiphar’s wife | Sinon’s Manipulation

Dante mentions the famous case of Potiphar’s wife, who attempted to seduce the Hebrew slave Joseph. When Joseph, in his virtue, refused her advances, she falsely accused him of assault. Her lie—born of wounded pride and desire, led to Joseph’s unjust imprisonment. It is for this deliberate falsification of truth that Dante places her here in the Inferno.

In contrast, Sinon was the Greek whose deceit led to the fall of Troy. It was he who convinced the Trojans to accept the wooden horse, a supposed offering to Athena, a symbol of the Greeks’ feigned surrender. His words cloaked betrayal in the language of humility, and his fraud unbolted the gates of the city, unleashing ruin.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

“Less shame would wash away a greater fault

than was your fault,” my master said to me;

“therefore release yourself from all remorseand see that I am always at your side,

should it so happen—once again—that fortune

brings you where men would quarrel in this fashion:to want to hear such bickering is base.”

Singleton 554

Singleton 557

Interestingly enough, Holland describes here Persian God Ahura Mazda (around 700 BC). The idea of Good and Evil, Truth and Lie takes some of its origins from there, but this deserves a whole another long post which I simply won’t be able to explore deeply here. Nevertheless, the wisdom behinds these words resonate.