How to Overcome Self-Doubt (Dante Read-Along)

Canto II: They can, because they think they can. (Week I)

They can, because they think they can.

~ from Virgil’s Aeneid, Book V, 231

(possunt, quia posse videntur.)

Welcome to Dante Read-Along

Welcome to Dante Read-Along, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this second Canto he reveals to Dante why his companion managed to escape the dark forest. You can find the main page of the read-long right here, reading schedule here, and the list of characters here (coming soon).

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, spiritual exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character and symbolism explanations.

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox click here for the web version)

This Week’s Circle ⭕️ :

Dante invokes the Muses, Genius, and Memory - He praises those who have journeyed into the underworld before him and questions his own worth to do the same - Virgil’s speech relating how he came to help Dante through the three blessed women Mary, St. Lucia, and Beatrice - Dante is emboldened and accepts the guidance given - They enter the path and begin their journey.

Canto II: Summary

As evening set, Dante prepared not to rest, but to continue his great work; “I myself / alone prepared to undergo the battle / both of the journeying and of the pity” (II.3-6). Here can be considered the true beginning of the journey, as Dante invokes the Muses, Genius, and Memory. Canto I, in this light, can be seen as a prologue to the work.1 This invocation to divine help is a traditional beginning of an epic work; while waiting until Canto II is unconventional, Virgil was also unconventional in his invocation in the Aeneid. Rather than asking the Muses to sing to him for inspiration as Homer does in line 1 of the Odyssey - “Sing to me of the man, Muse”2 - he waits until line 8 to invoke them; and Virgil does not simply wait: he opens the Aeneid with “Wars and a man I sing,”3 placing the work of the poem onto himself rather than onto the Muses.

Dante is embarking on a journey into the underworld, as many before him had famously done. He continues to praise the founding of Rome by Aeneas, although we will see his chastisement of his ages current incarnation of the city with it’s avarice, greed and corruption through the figures he meets as he journeys through Hell. He praises also the successor of Peter - the Pope - as the holder of the Keys of the Kingdom, as found in the New Testament: “And I will give unto thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven.”4 Thinking on these things, Dante does not consider himself as worthy as those who came before him in taking his own journey of descent into the underworld. “Therefore, if I consent to start this journey” he says to Virgil, “I fear my venture will be wild and empty” (II. 34-35).

In the epic simile that follows this admission of his own shortcomings (II.37-42), Dante understands that his thinking and emotional mind have taken over his reason; “with all my thinking I annulled / the task I had so quickly undertaken” (II.41-42).

Virgil acknowledges his doubts, but gently corrects him and points out that cowardice is “distracting him from honourable trials” (II.47), the furnace through which all of us must pass to attain growth and transformation. Virgil will help to deliver him from this fear, and here begins an extended speech explaining how he came to be there to help Dante as his guide.

Virgil had been in Limbo “among those souls who are suspended” (II.52) when he was visited by a lady “so blessed, so lovely” (II.53), who addressed him as one who had achieved the immortality of fame. The blessed and lovely one was Beatrice, who had seen Dante’s loss and confusion, and fearing that she was already too late to help him, she came to Virgil - from the Empyrean realm and prompted by love - and implored him to go to Dante and be his guide.

In reverence, Virgil accepts the charge laid out before him, wondering why she would risk coming so far into the outskirts of hell to tell him so. She reassures him, however, that she is not afraid, because “one ought to be afraid of nothing other / than things possessed of power to do us harm, / but things innocuous need not be feared” (II.88-90). How much then, do we go through life fearing things that have no power over us?

Beatrice tells Virgil of a “gentle lady” (II.94), who in regard for all humanity suspends judgement in favor of a perfect compassion - the Virgin Mary. It was she who had first seen Dante suffer, and called upon St. Lucia - the patron saint of sight and clear vision - to take action. St. Lucia then called upon Beatrice, friend of Dante, who was sitting with Rachel, wife of the Old Testament Patriarch Jacob, and admonishes her for letting the suffering Dante wander lost. His help has arrived from the highest heaven, and the three blessed women parallel the three invocations made at the beginning of Canto II, inspiring guidance, inspiration, and the poetic voice.

Virgil, upon hearing this story from Beatrice herself, took action immediately and came to Dante, saving him from the beasts at the very last moment, the beast that “barred the shortest way up the fair mountain” (II.120). Here then, is the necessity of Dante undertaking his long journey, that there is no shortcut to attainment, that both Dante and ourselves must take the long road of discovery and purification to the highest levels of being and understanding.

With all of this support behind him, Virgil cannot fathom that Dante can still hold back.

Why, why do you resist?

Why does your heart host so much cowardice?

Where are your daring and your openness

as long as there are three such blessed women

concerned for you within the court of Heaven

and my words promise you so great a good?

II.121-126

These are the final words that Dante needs to begin his first step into true transformation, and the ensuing epic simile expresses the embodiment of his transformation:

As little flowers, which the chill of night

has bent and huddled, when the white sun strikes,

grow straight and open fully on their stems,

so did I, too, with my exhausted force;

and such warm daring rushed into my heart

that I - as one who has been freed - began:

II. 127-132

Now, rather than crouching in cowardice, he longs for the journey. Think of that change: he longs for the journey. His will has aligned with Virgil’s will, he has aligned himself with Reason rather than fear and can truly begin. Dante steps onto “the steep and savage path” (II.142).

Philosophical Exercises.

How to Conquer Cowardice?

(Three Graces: Mercy, Light and Thought)

I. ‘Fear’ against ‘Word’

The key word of the first canto is paura (fear), whereas the key word of the second canto is parola (word). Interestingly, both terms appear five times in their respective cantos, emphasising their thematic significance.

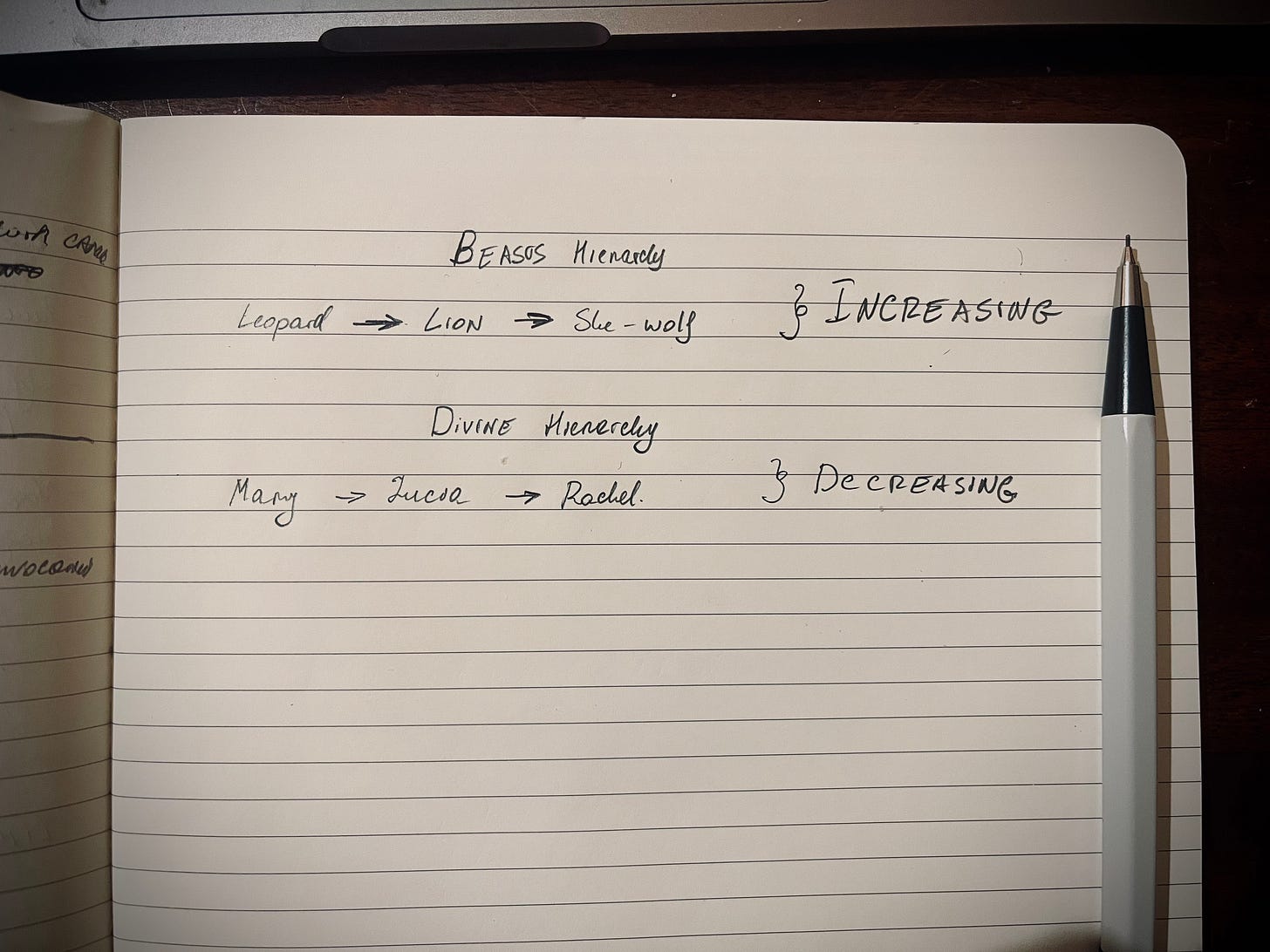

Dante made the first two cantos intentionally symmetrical. The first canto begins with Dante finding himself gripped in fear, in the second full of cowardice. In the first canto he meets three beasts whilst in the second he is told about three graces. Finally, both cantos end with Virgil’s assurances about the journey. (There is one more symmetry about which I will tell at the end of this part)

Why Dante chose the word ‘fear’ as the key word for the first canto requires no explanations, but why did he choose the word ‘word’ for the second?

Of course, we can refer to the Bible: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God’, but there remains a piece of a puzzle missing.

II. Hierarchy of Strengths and Weakness

These words ‘And just as he who unwills what he wills and shifts what he intends to seek new ends… I annulled the task I had so quickly undertaken’ (lines 37-41) shook me to the core when I first read them years ago.

How often have I undermined my noble aims through my own doubt? I wish I could say it happened only once in my life, but even when I planned this read-along seven months ago, I knew I was working toward something noble—yet I was still, to borrow Virgil’s words, ‘assailed by cowardice.’ There were many great minds who explored The Divine Comedy before me, who am I to attempt the same?

I doubted as Dante does in this canto. Aeneas journeyed to the underworld and so did Saint Paul, but their journeys were divinely authorised; what makes Dante think that he can do the same?

This is when the symmetry of Dante’s masterpiece becomes important. We know that Dante faced three beasts when he left the shadowed forest but the order that they appeared to him are crucial. They appeared in ascending order: leopard, lion and the scariest of them all - she-wolf.

It is different with the Three Graces that Beatrice mentions to Virgil. Mary, “a gentle soul” who symbolises compassion and holds the highest place in the hierarchy, interceded for Dante. She called upon Lucia, the embodiment of sight and clarity of thought, to intervene. Finally, Rachel, the third in this divine order, represents the contemplative life. If the beasts Dante encountered in the previous canto approached him in ascending order of fearfulness, grace approached to him descending from the highest realms of Heaven.

Virgil reminds his companion of his divine origins and that through contemplative life (Rachel) Dante can reach clarity of insight (Lucia) and unite with Beatrice (Love).

This journey was granted by ‘a gentle lady,’ Mary herself, and the words that Virgil speaks toward the end of the canto are among the most beautiful I have ever read—both in the original and in any of the English translations.

What is it then? Why, why do you resist?

Why does your heart host so much cowardice?

Where are your daring and your opennessas long as there are three such blessed women

concerned for you within the court of Heaven

and my words promise you so great a good?”

III. How to Conquer Cowardice?

‘If a man knows not to which port he sails, no wind is favourable’. Three Heavenly Ladies remind Dante of his divine origins, but why do they send Virgil to help?

At the start of her conversation with Virgil, Beatrice refers to Dante as her “friend” and notes that he has not been a friend of fortune. This is not simply a matter of “bad luck.” For Dante, deeply influenced by Boethius, relying on fortune is a doomed endeavor. Fortune’s wheel spins unpredictably, and when she grants favor, it is not through one’s own actions but solely her whim. Therefore, any happiness she bestows cannot truly be credited to the recipient.

Dante tries to climb out of his own peril by the power of his own strength, not because of fortune’s wish. Beatrice continues on by saying:

Go now; with your persuasive word, with all

that is required to see that he escapes,

bring help to him, that I may be consoled.

Virgil, the most noble and the greatest poet of antiquity, is chosen by Beatrice and the Divine Graces because with his ‘persuasive word’ he can articulate to Dante the path out.

In other words, to overcome our cowardice and confront the demons that terrify us, we must give them form and articulate them to ourselves. Virgil is not only Dante’s guide through Hell but also the one holding its metaphorical map, directing his companion with his “persuasive word.” Virgil undoubtedly symbolises reason—a reason that is deeply intertwined with Divine Grace.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Themes 🖼️ :

Nine Muses - Dante invokes nine Muses of classical antiquity (more on each of them below). It cannot be coincidence that there are also 9 invocations throughout The Divine Comedy, according to Hollander

Descent into the underworld - the theme of visiting the underworld and ascending to acquire wisdom appears several times in mythology and religious texts. The two cases that Dante mentions here and compares himself to are Aeneas and St. Paul. Interestingly enough both Muses, Aeneas and of course Virgil are heroes of pre-Christian world.

Fortune -it is only through this read-along that I began to truly notice the profound influence Boethius had on Dante, particularly regarding the concept of the Wheel of Fortune. When we succeed under Fortune’s favour, we cannot claim credit for it—it is purely luck, independent of any effort on our part. That is why Beatrice mentions that her friend Dante is no friend of Fortune, Dante’s desire to escape the shadowed forest is the result of his effort only.

The role of the guide - Through this read-along, I feel I’ve gained a deeper understanding of Virgil’s nature. While almost every commentator emphasises that Virgil symbolizes reason, Dante presents reason as something far richer than the Enlightenment’s focus on logic and lack of superficial way of thinking. In Dante’s vision, reason is inspired by love, contemplation (not mere thinking), mercy, and kindness.

Quotes 🖋️ :

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom)

As little flowers, which the chill of night

has bent and huddled, when the white sun strikes

grow straight and open fully on their stems,so did I, too, with my exhausted force;

Characters:

- Beatrice - The beloved of Dante, she who awakened him to a greater Love. Beatrice is the guide who takes over for Virgil after Purgatory and guides Dante through Paradise.

- Memory - Mnemosyne, or the Goddess Memory, was of the Titans. Zeus lay with her for nine nights in a row, and she gave birth to nine daughters, the Muses. They are the goddesses of the arts and music, the inspiration of countless artists, writers, and poets, who would invoke them for the creative energy that they inspired.

- Muses - The nine daughters of the Goddess Memory who inspire the arts. The nine are: Calliope = Lovely Voice = Epic Poetry; Clio = Renown = History; Euterpe = Gladness = Lyric Poetry; Thalia = Good Cheer = Comedy; Melpomene = Singer = Tragedy; Terpsichore = Delighting in the Dance = Dance; Erato = Loveliness = Love Poetry; Polyhymnia = Many Songs = Hymns to the Gods; Urania = Heavenly One = Astronomy.

- Genius - In the ancient and medieval world, Genius was not considered as something that came from within the artist, but as a force working through them as a gift from the divine, similar to the action of the Muses with their gift of inspiration. In antiquity, Genius was likened to the daimon of Socrates - not our modern concept of demon, into which the idea transformed - rather a dweller of the heavenly realms. Socrates claimed that he was given guidance from his daimon. Because of this, “poetry was so often likened to prophecy and prophets to poets.”5

- Mary - The Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus, Queen of Heaven.

- Lucia - St. Lucia was a Christian Martyr who was killed in the year 304. She is the bearer of light and symbolizes clear vision and understanding.

- Rachel - In the Old Testament book of Genesis, Rachel was married to Jacob, the father of the twelve tribes of Israel, and was also the mother of Joseph. She represents contemplation, where her sister Leah represented activity.

Dorothy Sayers, The Divine Comedy: Hell Introduction, 83

Homer Odyssey I.1

Virgil Aeneid I.1

Matthew 16:19 King James Version

Darrin M. McMahon, Divine Fury 11

Seneca said “We suffer more from imagination than from reality.”

I’ve wonder what inspired or haunted Dante’s extraordinary imagination, and the sources of his vivid imagery. I don’t believe it’s just Christian or secular iconography. I think Dante’s fears had a founding well before he created the Commedia.

I was struck, as a veteran, by two word choices in lines 3-6: “battle” and “memory.” Why did he characterize what was coming as “battle,” rather than, say, a struggle, passage, or pilgrimage? That peculiar word choice, and his reference to “memory” are (I infer) after-effects of his military experience — memories that are also reflected elsewhere in the Commedia.

While the historical record is thin, most researchers believe he experienced combat as a cavalryman at the bloody Battle of Campaldino in 1289, and perhaps at the siege of the fortress of Caprona in August of that year. Did the emotional toll of his experience (alongside his expulsion and exile) color his imagination? The book “Campaldino 1289: The Battle That Made Dante,” by Kelly Devries and Niccolo Cappani makes a strong case for the impact of his military experience on his imagination and the Divine Comedy.

There’s a saying “It is easy to laugh at the shadows when the night has passed.” (Virgil: “As phantoms frighten beasts when shadows fall.”) I don’t think Dante’s “night” had passed when he wrote the Commedia. Many of the shadows that haunted him, and that he portrayed so viscerally, seem to have had their earthly origin on the field of battle. It was just ten years before Good Friday, 1300 that he had seen a very compact battlefield littered with ~2,000 dead. In a letter (for which we have but a fragment) he said: “…ten years had already elapsed since the Battle of Campaldino, in which the Ghibelline party was almost utterly defeated and effaced, where I found myself no youngster in the practice of arms, and where at the beginning I felt great fear, and in the end even greater joy through the varying fortunes of that fight.”

Now, in the Dark Wood, he steels himself for battle yet again. He questions whether he’s prepared. “…With all my thinking” sounds suspiciously like flashbacks. He doubts he’s worthy. He is not a warrior in the heroic sense of Achilles, or Aeneas, and fears he may be on the verge of the warrior Ulysses’ recklessness: “I fear my venture may be mad.” He comes across as a reluctant veteran pondering the seeming foolishness of this undertaking. In Henry V, Shakespeare has the Duke of Orleans (in real life an accomplished poet) say “That’s a brave flea that dares to eat his breakfast on the lip of a lion.” I get the sense that here, particularly after his encounters in Canto 1, Dante feels like that flea.

What, then, convinced him to take that first step on the “Steep and savage path?” Virgil’s eloquent words? Reuniting with Beatrice? Or was it Virgil’s searing taunt — accusing him of having “a soul assailed by cowardice”? I can think of no greater insult in the chivalric code of Dante’s day. Virgil’s chiding echoes the poet Robert Frost: “The best way out is always through.“

Thank you for the insights into the detailed symmetry between the first two cantos - I completely missed most of this in my own reading!

The line: ‘And just as he who unwills what he wills..." makes me think of the 'To be or not to be' soliloquy in Hamlet which ends:

"Thus conscience doth make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry

And lose the name of action."

Quotes: I also like the John Ciardi translation of Virgil's admonition of Dante and the 'little flowers' simile:

"And now what ails you? Why do you lag? Why

this heartsick hesitation and pale fright

when three such blessed Ladies lean from Heaven

in their concern for you and my own pledge

of the great good that waits you has been given?"

As flowerlets drooped and puckered in the night

turn up to the returning sun and spread

their petals wide on his new warmth and light -

just so my wilted spirits rose again

and such a heat of zeal surged through my veins

that I was born anew.”

PS Thank you for including all the wonderful paintings and illustrations. They're a joy to look at.