Hypocrites: Saints Abroad, Devils at Home

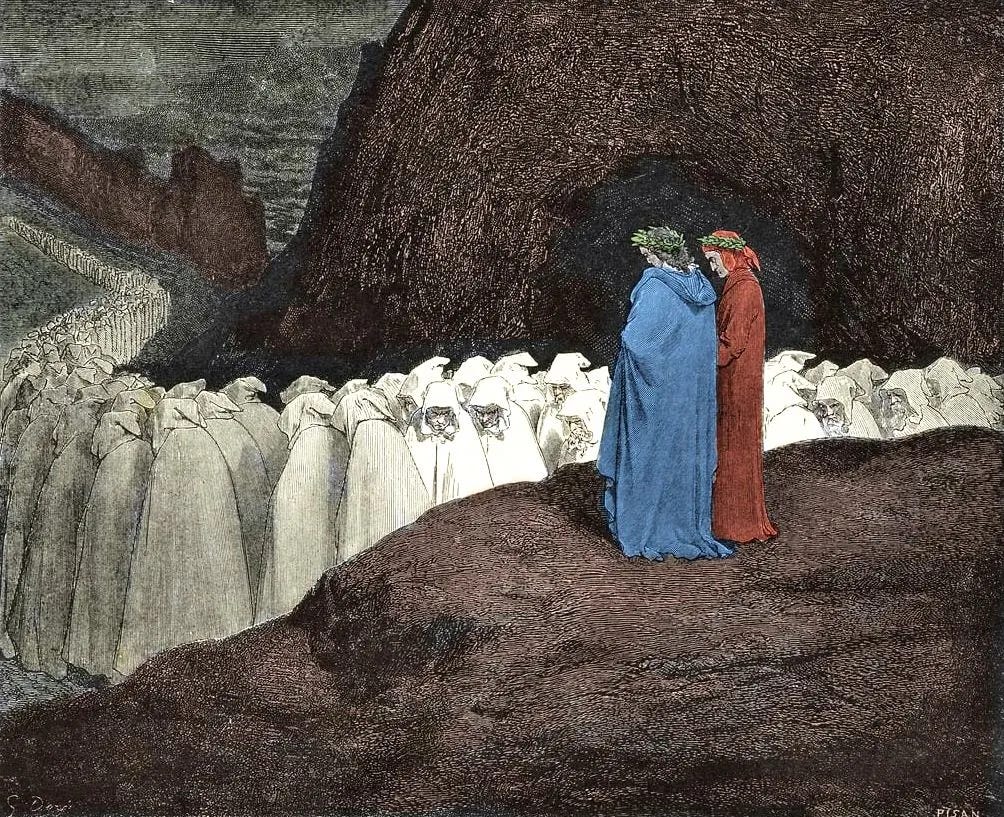

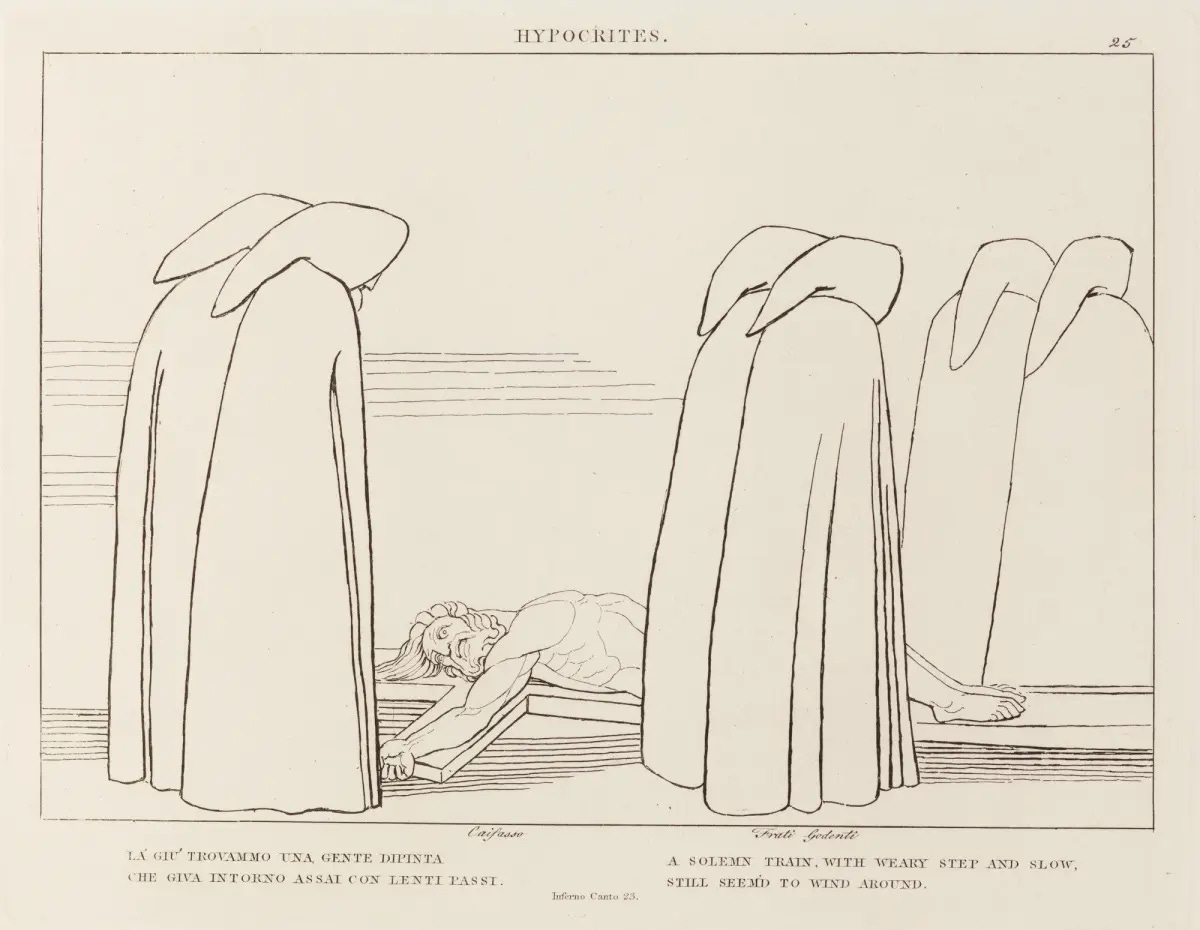

(Inferno, Canto XXIII): Hypocrites, Caiaphas, Jovial friars

The only vice that cannot be forgiven is hypocrisy. The repentance of a hypocrite is itself hypocrisy.

~ William Hazlitt, essay ‘Characteristics’

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

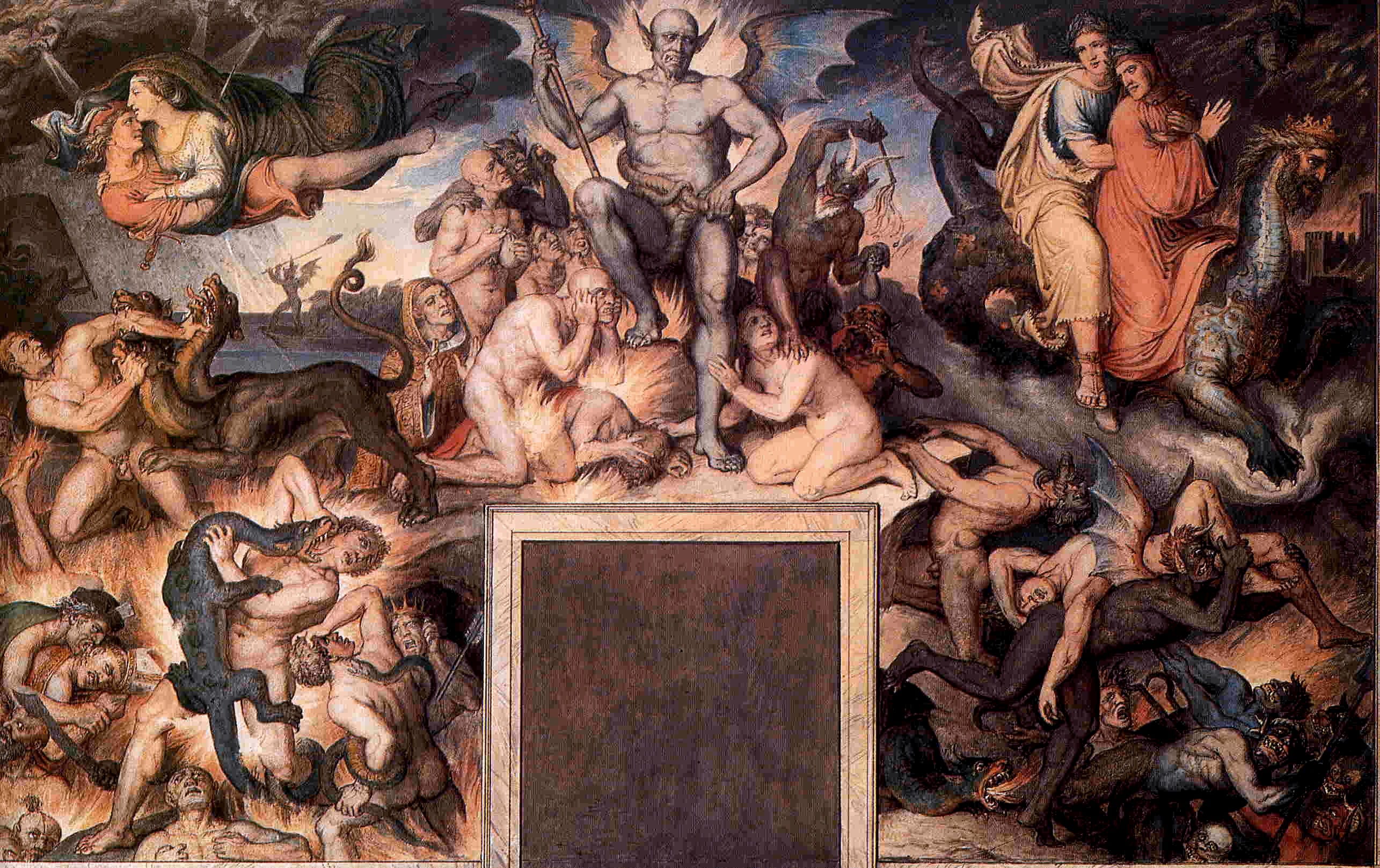

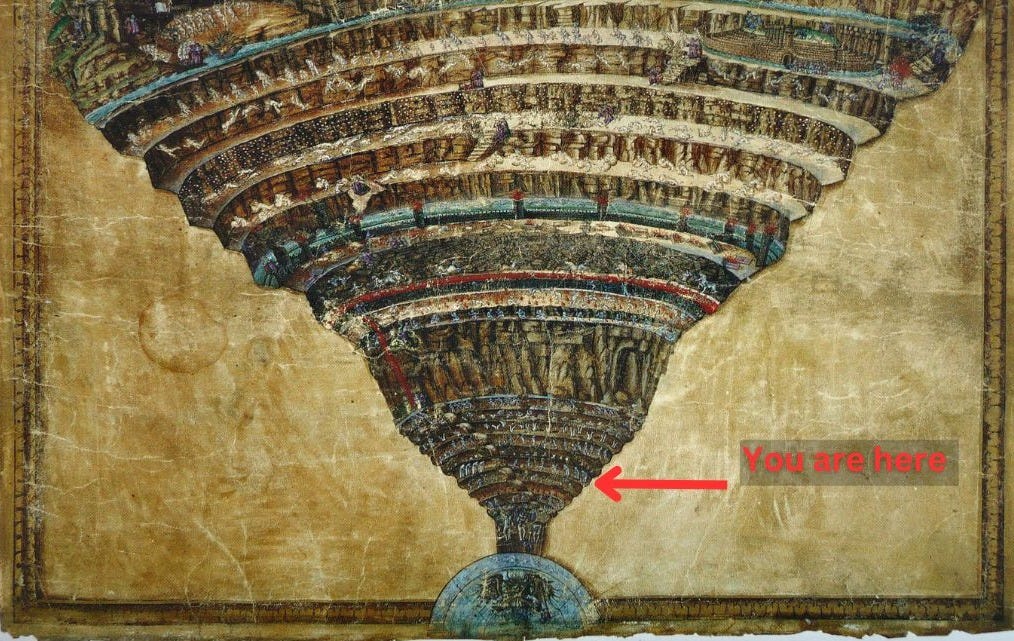

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Twenty-Third Canto we enter the sixth pouch of the Eighth Circle and find the Hypocrites. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Eighth Circle, Sixth bolgia - Virgil and Dante have left the demons behind - They fear being followed - The demons appear in pursuit - Virgil holds Dante and slides into the Sixth bolgia - The Hypocrites, walking slowly in file - Golden cloaks lined with lead - Jovial Friars - Caiaphas - Truth of the broken bridges and the lie of the demons.

Canto XXIII: Summary

After slipping away from the chaotic scene with the pitch-covered demons in the fifth bolgia, Dante and Virgil moved silently away, in file like Franciscan monks. Dante thought of Aesop, and his fable of the mouse, the frog, and the hawk. The scene they had just witnessed reflected to Dante the possible fate of those players. This thought gave birth to new, more frightening ideas;

And even as one thought springs from another,

so out of that was still another born,

which made the fear I felt before redouble

XXIII.10-12

As he thought about the fallout from the incident with the demons and the escaped Navarrese, Dante became even more fearful, telling Virgil he could heard them coming up behind them. Virgil is in tune with him:

And he to me: “Were I a leaded mirror,

I could not gather in your outer image

more quickly than I have received your inner.

For even now your thoughts have joined my own;

in both our acts and aspects we are kin--

with both our minds I’ve come to one decision.”

XXIII.25-30

Their fears were justified; as the fifth bolgia demons approached them, Virgil protectively caught Dante up and slid with him down into the trench of the sixth bolgia, narrowly missing them. Being masters only of their own realm, the demons could not follow them past it.

Dante and Virgil immediately encounter the sinners of the sixth bolgia, cloaked in brilliant and beautiful voluminous cloaks:

And they were dressed in cloaks with cowls so low

they fell before their eyes, of that same cut

that’s used to make the clothes for Cluny’s monks.

Outside, these cloaks were gilded and they dazzle;

but inside they were all of lead, so heavy

that Frederick’s capes were straw compared to them.

A tiring mantle for eternity!

XXIII.61-67

A reputed punishment set by Emperor Frederick II used leaden cloaks draped over those to be executed, and then set into the fire to melt over the convicted; yet even these were light compared to the cloaks they saw before them. As they walked alongside, they quickly outpaced the weary and slow pace of the sinners. Dante asks Virgil to help him find a familiar face. Behind them, one of the sinners called out, and they slowed to walk in time with him.

Two shades, eager to speak with them but delayed by the heaviness of their cloaks, strained forward. They seemed to think and speak as slowly as they moved as they considered Dante and Virgil, questioning if Dante was alive and why they were not mantled in the heavy cloaks of punishment. They announce the sin of this bolgia as an “assembly of sad hypocrites” (XXIII.92), and want to know where Dante is from.

Moreover when ye fast, be not, as the hypocrites, of a sad countenance: for they disfigure their faces, that they may appear unto men to fast. Verily I say unto you, they have their reward.

Matthew 6:16 KJV

He tells them of Florence by the river Arno, qualifies that he is indeed still living, and asks about their sin and their punishment. These two are Jovial Friars from Bologna: Catalano and his companion Loderingo.

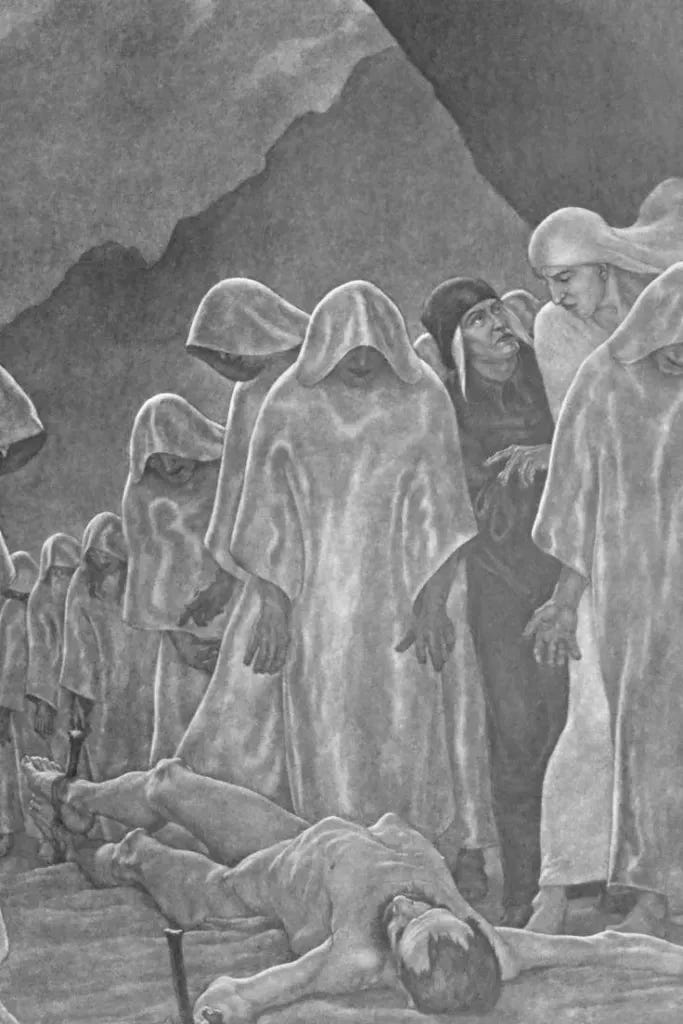

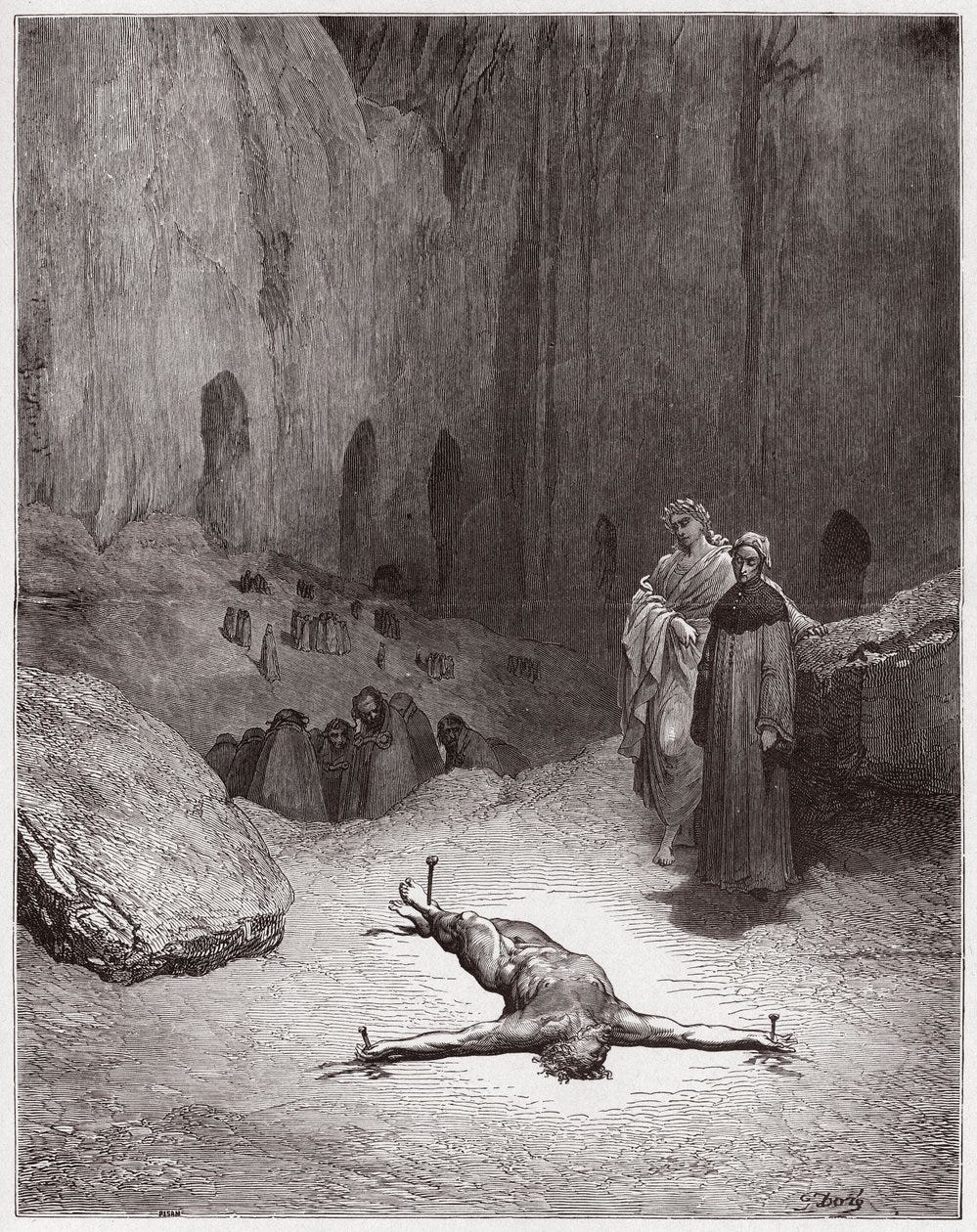

But as Dante went to add to this conversation, he was stopped suddenly by the presence of a sinner on the ground before them, stretched out and crucified with stakes through his hands and crossed feet. This is Caiaphas, pivotal in the role of the crucifixion of Jesus.

Naked, he has been stretched across the path,

as you can see, and he must feel the weight

of anyone who passes over him.

XXIII.118-120

The Jewish people of the first century, by their own law, could not put one to death; Jesus had to be put into the hands of the Romans, and this is where Caiaphas acted. Crucifixions, in the Roman Empire, were reserved for the most terrible of criminals.

Then gathered the chief priests and the Pharisees a council, and said, What do we? for this man doeth many miracles. If we let him thus alone, all men will believe on him: and the Romans shall come and take away both our place and nation. And one of them, named Caiaphas, being the high priest that same year, said unto them, Ye know nothing at all, nor consider that it is expedient for us, that one man should die for the people, and that the whole nation perish not. And this spake he not of himself: but being high priest that year, he prophesied that Jesus should die for that nation; John 11:47-51 KJV

Caiaphas and the others who acted against Christ were thus punished; Virgil is staring down at Caiaphas in amazement, as he is newly there since the last time that Virgil made his way down into the depths of these realms of Hell.

Yet it is time to find their way through and past this bolgia, and Virgil asks direction to the best passage out so that they can continue their journey without encountering the demons again. Catalano then explains that every bridge over the sixth bolgia is broken, and that they must climb up the tumbled rocks just as Virgil had slid down them earlier.

At this Virgil realizes the deception that the demons had played, and his anger comes to the surface as Catalano gives the closing thought, that:

In Bologna, I

once heard about the devil’s many vices—

they said he was a liar and father of lies.

XXIII.143-144

[The devil] was a murderer from the beginning, and abode not in the truth, because there is no truth in him. When he speaketh a lie, he speaketh of his own: for he is a liar, and the father of it. John 8:44 KJV

As Virgil strode away, Dante followed the thing most precious to him in the bleak landscape of hell, the prints of the Poet.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

“Away, and mock the time with fairest show; False face must hide what the false heart doth know.”

~ Macbeth, William Shakespeare

‘A saint abroad, and a devil at home,’ writes John Bunyan in The Pilgrim’s Progress, echoing the same sentiment found in one of the Psalms. The reason why it is so difficult to fully perceive what hypocrisy actually is was well articulated by the English version of Dante—John Milton—who, in his Paradise Lost, wrote:

For neither man nor angel can discern

Hypocrisy, the only evil that walks

Invisible, except to God alone,

By his permissive will, through heav'n and earth.~ Book III, line 682

How can we truly grasp the nature of hypocrisy, when it so often hides in plain sight and wears so many guises? If I had to point out in which part of Geryon’s body Hypocrisy dwells, I would point to his ‘just face’ as Dante describes.

“I believe that one of the things Christianity says” writes Ludwig Wittgenstein “is that sound doctrines are all useless. That you have to change your life. (Or the direction of your life.)” Wittgenstein’s often enigmatic message is this: we may read endless wise quotes, but unless they shift our direction or transform our character, they are of no use. The true belief is not a worship of dogmas, even if they are sound and wise, but a continuous spiritual transformation. And yet hypocrisy is not merely when our words do not match our deeds. It is not only when you do not practice what you preach.

I. Saints abroad and devils at home

The Russian-American poet Joseph Brodsky once said that ‘life—the way it really is—is a battle not between good and bad, but between bad and worse.’ I cannot entirely agree with his sentiment and the reason for this is Dante’s vision.

In the sixth bolgia we witness a horrifying scene: we see Caiaphas, who once was a Jewish priest, crucified to the ground, and all the hypocrites stepping over his body each time they pass him.

Caiaphas, the high priest, feared unrest, and it was through the plot he orchestrated that Jesus was arrested and handed over to the Roman authorities. His justification for this (in his words) was:

“It is better for you that one man die for the people than that the whole nation perish.”

He presented his action as sacrificial wisdom but in truth it was moral abdication. A hypocrite, in Dante’s vision1, is not merely a soul whose beliefs and actions do not align, for Dante a hypocrite is a person who—like Caiaphas—hides vices in the language of spirituality. In the great Italian’s worldview the true sacrifice is always voluntary, while Caiaphas used it as a political instrument for his own interests.

He used moral reasoning to justify an immoral action.

This is why I disagree with Brodsky—his reasoning echoes that of Caiaphas: that we must either sacrifice one man, which is bad, or allow an entire nation to fall into unrest, which is worse.

If we follow this reasoning good can never emerge.

II. Devaluation

I apologise to my reader if I return to this point too often, but it bears repeating: the very essence of fraud lies in its power to devalue what is most meaningful in life. Seducers devalue love; flatterers, the word; simonists, the Church; diviners, nature and time; barrators, government and society; hypocrites—perhaps most dangerously—devalue values themselves.

The nature of hypocrisy could fill volumes—each page tracing the lives of figures like Cardinal Thomas Wolsey or Tomás de Torquemada. To paraphrase Milton, the hypocrite’s greatest skill is invisibility; so well do they wear the mask of virtue that only the most discerning—or God himself—can truly unveil and study them.

In Dante’s vision the hypocrite is not only a person who leads a double life, pretending to be virtuous whilst being bad all the time, but also one who devalues virtue itself by equating it with pragmatism. To reduce the good to the merely useful is, for Dante, a form of spiritual fraud.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Aesop’s fable

Most editions of The Divine Comedy include a brief retelling of Aesop’s fable in which a mouse asks a frog for help crossing the water. The frog agrees but secretly intends to betray the mouse. He ties the mouse to his own leg and dives, trying to drown it—yet their struggle attracts a hawk, who swoops down and seizes them both. In the end, betrayer and betrayed perish together.

In some sense this fable acts as a perfect bridge between the corrupt devils of canto 22 and hypocrites we meet in canto 23. It beautifully ties together the fact that in the full fable, the frog acts as a hypocrite when he offers himself as a virtuous creature that can help the mouse.

The word ‘Già’

Già mi sentia tutti arricciar li peli

de la paura e stava in dietro intento,

quand’ io dissi: «Maestro, se non celite e me tostamente, i’ ho pavento

d’i Malebranche. Noi li avem già dietro;

io li ’magino sì, che già li sento.lines 19-24

There is a deep and beautiful tension within The Divine Comedy—a kind of spiritual paradox. Dante’s journey, from the dark wood to the heights of Paradise, is granted and sustained by Divine grace. In that sense, it is inevitable, woven into the very fabric of Providence. And yet, again and again, we see the pilgrim afraid—afraid of failure, of sin, of being seized by devils or losing his way.

This is where the word già (“already”) plays a quiet but powerful role. Dante uses it precisely in moments when fear or uncertainty creeps in, when the outcome is not yet visible. Già places the event in the past—something has already happened—but it often introduces a strange dissonance: the “already” is haunted by a feeling that perhaps what was done is not yet secure, not yet completed.

And so, even though the path is guided by Heaven, Dante must still walk it—step by trembling step. This echoes Boethius’s philosophy in The Consolation of Philosophy: that God’s providence encompasses all, but within that divine order, human free will still exists. The eternal sees the whole, but within time, we must still choose.

It’s not a contradiction. It is, rather, a mystery—like grace itself.

Virgil’s Authority

In Canto XXIII, Virgil and Dante come to the grim realisation that the bridges Malacoda promised do not, in fact, exist—they have all collapsed. The devils’ directions were lies, and here we witness something deeply unsettling: Virgil’s authority begins to waver. He, the symbol of human reason, should have known better than to place trust in the mouth of deceit itself.

What’s more, if we closely examine the previous two cantos—XXI and XXII—we find that Dante’s instinctive caution stands in contrast to Virgil’s confident boldness. The pilgrim’s unease turns out to be justified. The devils, masters of manipulation, lured them with false promises, and now, amid the cloaks of the hypocrites, their failure becomes evident.

The Bolognese hypocrites mock Virgil’s error with biting irony. It is one of the few moments where reason is humbled by cunning fraud.

At which the Friar: “In Bologna, I

once heard about the devil’s many vices—

they said he was a liar and father of lies.”

In this scene, Dante seems to suggest that even reason, when isolated from grace and intuition, can be misled. Wisdom, perhaps, is found not only in learned authority but in the union of intellect and moral discernment—of Virgil’s knowledge and Dante’s awakening conscience.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

At which the Friar: “In Bologna, I

once heard about the devil’s many vices—

they said he was a liar and father of lies.”And then my guide moved on with giant strides,

somewhat disturbed, with anger in his eyes;

at this I left those overburdened spirits,while following the prints of his dear feet.

Characters:

Aesop - The name given to the compiler of fables, many with animal characters and a moral statement at the end, from ancient Greece in the 6th century BC. It is agreed that there was probably not one historical Aesop responsible for all the fables. Many of them made their way into Latin versions in the Middle Ages. Here is a 19th century rendition of the fable of “The Mouse, the Frog and the Hawk.” There are many versions of the tale:

A MOUSE who always lived on the land, by an unlucky chance formed an intimate acquaintance with a Frog, who lived for the most part in the water. The Frog, one day intent on mischief, bound the foot of the Mouse tightly to his own. Thus joined together, the Frog first of all led his friend the Mouse to the meadow where they were accustomed to find their food. After this, he gradually led him towards the pool in which he lived, until reaching the very brink, he suddenly jumped in, dragging the Mouse with him. The Frog enjoyed the water amazingly, and swam croaking about, as if he had done a good deed. The unhappy Mouse was soon suffocated by the water, and his dead body floated about on the surface, tied to the foot of the Frog. A Hawk observed it, and, pouncing upon it with his talons, carried it aloft. The Frog, being still fastened to the leg of the Mouse, was also carried off a prisoner, and was eaten by the Hawk.

Harm hatch, harm catch.2

Jovial Friars: The Cavalieri di Beata Santa Maria was a religious order devoted to mediate peace during political turmoil. The sinners Catalano and Loderingo represented the Guelf and the Ghibelline factions respectively, and were both appointed the same executive position to bring fairness to proceedings. The “evidence near Gardingo” (XXIII.108) that Catalano refers to is the ruins of the Uberti estate destroyed by the Guelphs in party violence.

Caiaphas: Found in the New Testament Gospels, Caiaphas was the high priest of the Jews who gave Jesus up to Pilate for judgment. Annas, his father-in-law, was the one who helped to deliver him.

This is a Christian vision in general as well.

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/21/pg21-images.html#link2H_4_0088

JG Nichols has the Jovial Friars as the "Frisky Friars", makes it sound like you might expect to find them in a different circle