In Church With Saints, With Rotters in the Tavern

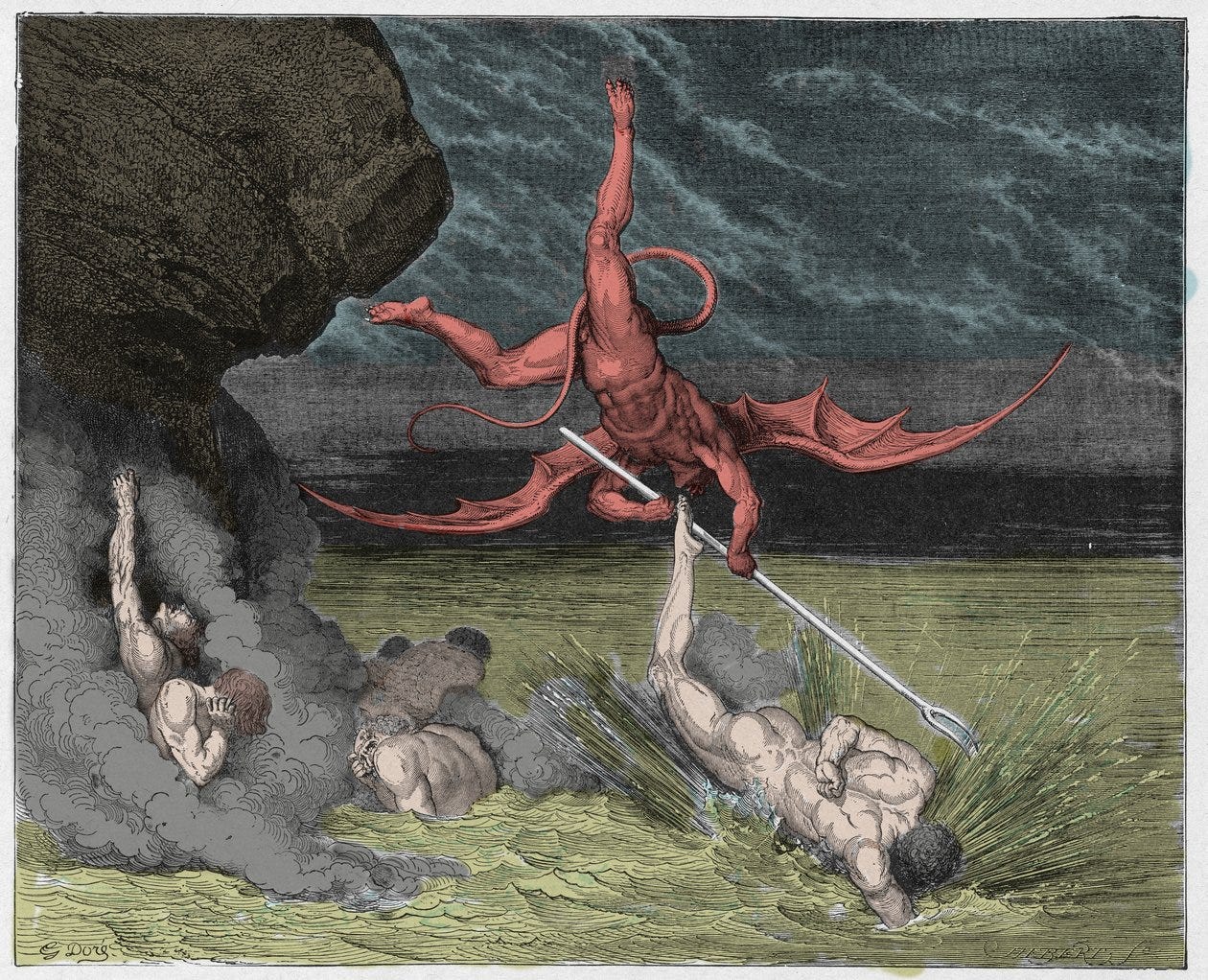

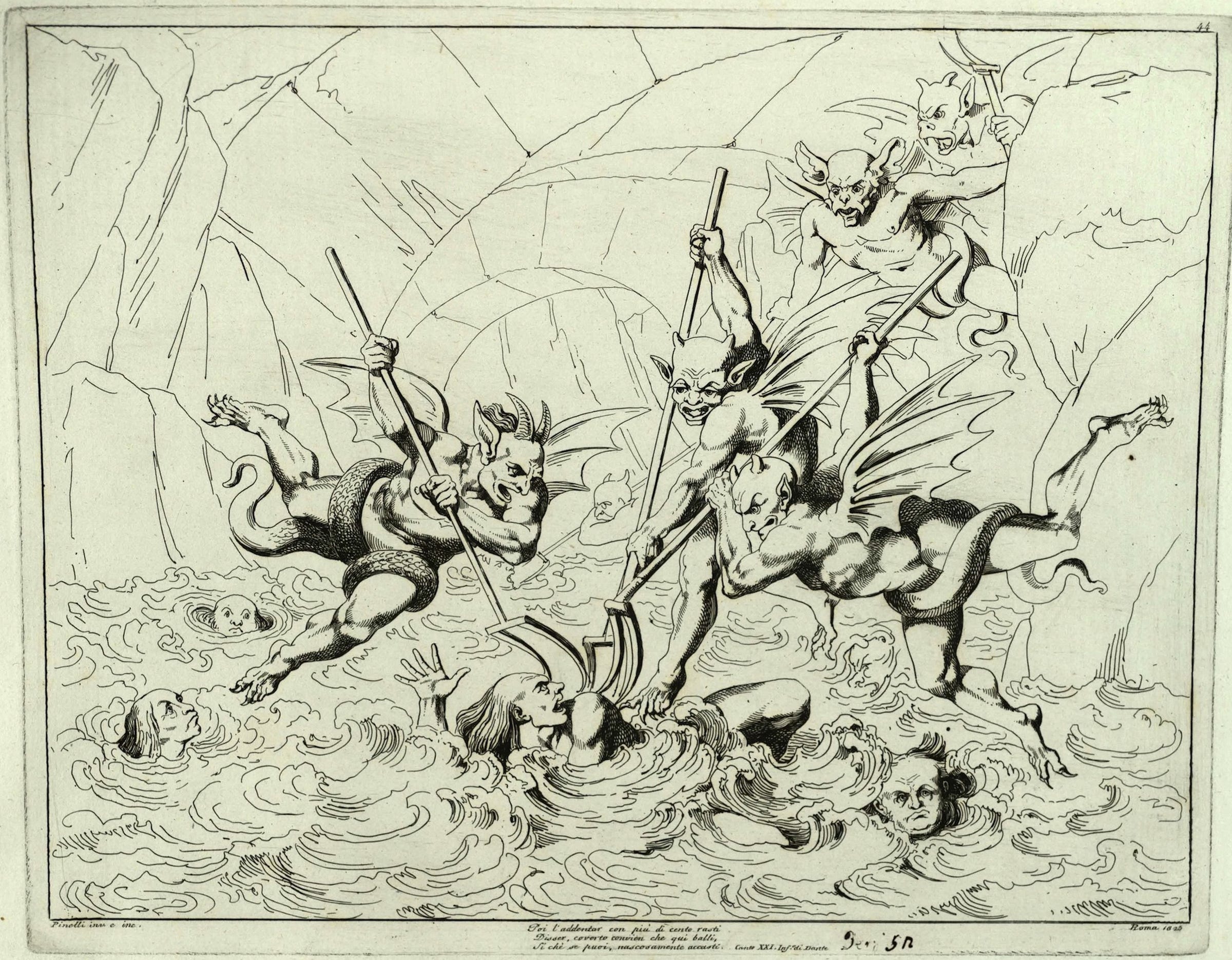

(Inferno, Canto XXII): Ciampolo, barrators and how to escape devils

Cram criminals together and see what happens, You get concentrated criminality, crime in the midst of punishment.

~ Anthony Burgess

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

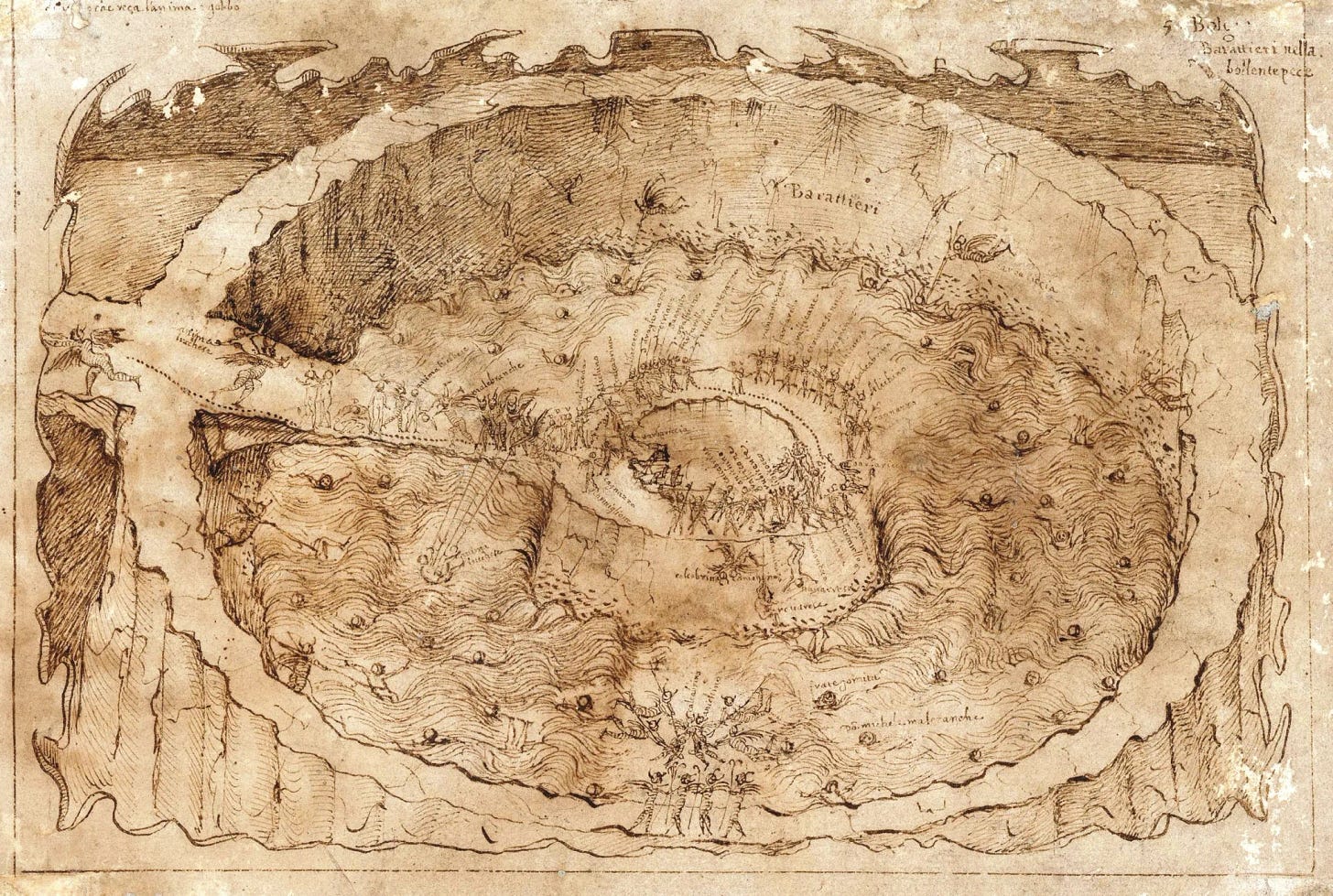

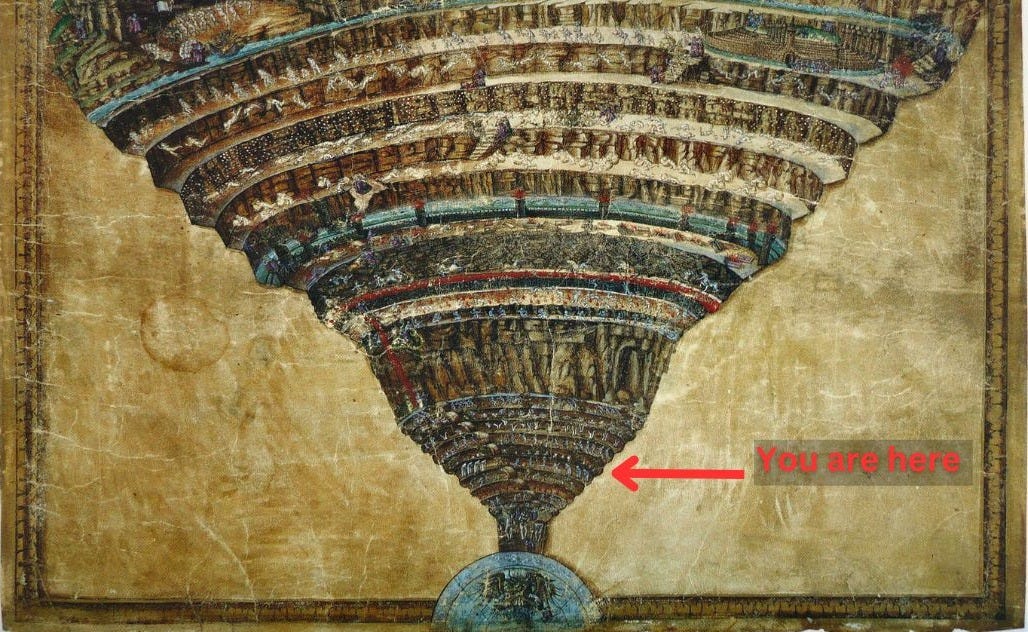

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Twenty-Second Canto we are still in the fifth pouch of the Eighth Circle with Barrators and Demons. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Eighth Circle, Fifth bolgia continued - A band of demons escorts Dante and Virgil seeking for a bridge to the Sixth bolgia - The Barrators in the boiling pitch - The sinner from Navarre caught and hooked - Demons taunt him, Dante and Virgil question him - The Navarrese escapes, tricks the demons, and chaos ensues - Dante and Virgil slip away.

Canto XXII: Summary

The art of horsemanship and cavalry and the many ways to ride in war and in the field are all known to Dante. He had fought in the battle of Campaldino between the Guelfs and Ghibellines, in which the Aretine Ghibellines were defeated; but as well as he knows all of these things, none of them have ever been announced by such a strange bugle call as he heard in the Fifth bolgia of the Eighth Circle.

Dante and Virgil were at the beginning of their escorted march to find a bridge over the sixth bolgia, and ten demons were guiding them along the rocky banks of the fifth trench, where they could see the barrators and grafters in the boiling pitch.

We made our way together with ten demons:

ah, what ferocious company! And yet

“in church with saints, with rotters in the tavern”

XXII.13-15

As he examines the pitch, the sinners that he sees conjure visions of animals, and their attempts to do anything to find relief from the painful, boiling trench.

A sinner might break the surface with its back like a dolphin to ease its pain, or leave their noses exposed, like a frog breathing in the fresh air, or even looking as an otter might, dripping with thick pitch, when lifted wet and sodden from the water.

With the approach of the ten demons who are guiding Virgil and Dante, all of these sinners who were trying to find relief quickly ducked under the surface - but one, too slow, was hooked by the demon Graffiacan. As the poor sinner hung there, the demons began to banter and tease - threatening mutilations that they were not afraid to perform. The visceral action of the demons toward the sinner, hooking him like a carcass, makes us shudder as Dante did in recounting it.

Though it may present an appearance of solidarity, Satan’s kingdom is divided against itself and cannot stand, for it has no true order, and fear is its only discipline.1

Dante steps into this drama to ask Virgil if they can speak to the sinner, hanging there on the demon hook, and Virgil approaches him and asks where he was from. He was from Navarre, and of the household of King Thibault. Benvenuto says of the king under which the sinner served, “he was a singularly just and clement man - more so than any other king of Navarre.”2 It was there that he had learned his arts of graft and barratry. He is not named in the Canto, but early commentators called him Ciampolo.

Another demon, Ciriatto, takes this moment to dig a single tusk into the sinner, continuing the play of torture they are enacting on him, as an evil cat pursues the mouse. Here, Barbariccia - the leader - holds the sinner, shouting to the other demons to get back, and all the while the sinner is hanging on the hook. Barbariccia tells Virgil to finish his questions before the other demons tear him apart, and Virgil asks him if there are other Italians he can report on that are there with him under the boiling pitch.

Yes, the sinner had just been with an Italian, and wished he were still with him, hidden from the malicious demons. The demons were at the end of their patience, hungry to act, and could not hold back:

Libicocco cried: “We’ve waited long enough,”

then with his fork he hooked the sinner’s arm

and, tearing at it, he pulled out a piece.

Draghignazzo, too, was anxious for some fun;

he tried the wretch’s leg, but their captain quickly

spun around and gave them all a dirty look.

XXII 70-75

Virgil continues his questioning, even as the unfortunate sinner examines the damage done by the torture, asking who the Italian was. He was Fra Gomita of Gallura, a friar of Sardinia, and chancellor to the governor of Pisa, Nino Visconti.

Who was a vessel fit for every fraud:

he had his master’s enemies in hand,

but handled them in ways that pleased them all.

He took their gold and smoothly let them off,

as he himself says; and in other matters,

he was a sovereign, not a petty, swindler.

XXII.82-87

Nino turned a deaf ear to all complaints against Fra Gomita until he discovered that the friar had connived at the escape of certain prisoners who were in his keeping, whereupon Nino immediately had him hanged.3

Within the pitch, Fra Gomita is companions with a fellow Sardinian, don Michele Zanche, believed to be the governor of Logodoro, a district of Sardinia in the thirteenth century.

But this is of the least concern to the Navarrese, as his fear of the demons surfaces again. Farfarello, making threatening gestures, is rebuked by Barbariccia, and the sinner continues speaking yet again.

He is happy to ask the Tuscans or Lombards who are below to surface to speak to Dante and Virgil, but to do that, he says, the demons must move away from the bank so that the shades will be willing to surface. They have an all clear signal of a whistle that the sinner will give which will bring up shades from below.

One of the demons announces that it must be a trick for the sinner to escape their hook and punishments! And with this, the Navarrese gives some foreshadowing into the next events:

To this, he who was rich in artifice

replied: “Then I must have too many tricks,

if I bring greater torment to my friends.”

XXII.109-111

As the demons went to hide, the sinner took his chance, and jumped free of the hook, diving back into the boiling pitch. Alichino, “he who had led his band to blunder” (XXII.125), immediately took after him, but even swift wings could not outrun the strength of the sinners fear, and he escaped. Calcabrina was looking for a fight, and once the Navarrese escaped, he turned on Alichina, and the two of them, fighting, plunged into the boiling pitch.

The chaos that reigned in the attempt to rescue the demons from the pitch - stuck there with coated wings - gave Dante and Virgil the perfect moment to slip away, unnoticed, from the pandemonium.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

It is not the young people that degenerate; they are not spoiled till those of mature age are already sunk into corruption.

~ Montesqieu

One of the great joys of this read-along is the community itself, and one of our members made a brilliant connection between the theme of government corruption in this canto and a fresco in the city of Siena titled The Allegory of Good and Bad Government.

Years ago, I had a printed copy of that very fresco hanging in my reading corner. I’ve never worked in government, so you might ask—why the Hell (or, why the Inferno) did I choose that particular piece of art for my wall?

To answer that question, I have to refer to another masterpiece—one I didn’t dare hang on my wall, though I studied it for some time: The Triumph of Death by Pieter Brueghel the Elder. Just a glance at the scenes unfolding in that painting evokes fear and hopelessness—destruction, fire, and all the nightmares we carry about what could befall a society when order collapses.

I think one-day I might do painting-read alongs, where we could go through all the works by great painters such as Bosch, Brueghel and Dürer and decipher the symbolism of each work one by one.

Famine and plague were two forces that our ancestors—and still many around the world—feared with trembling hearts. Yet these were sudden, often self-regulating powers of nature: she could destroy harvests with a shift in weather, or unleash plagues by seizing command over our very bodies.

Yet no plague, no famine, has wrought as much ruin as the corrupt man—whose womb gives birth to a corrupt government.

Death spares no one, neither guilty nor innocent, but corruption intensifies it. The figures in Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Allegory of Bad Government embody the very forces of destruction that Brueghel, with his meticulous eye for horror, sought to portray in The Triumph of Death.

I. In Church with Saints, With Rotters in the Tavern.

To be virtuous does not mean to be gullible; in fact, the very purpose of Dante’s journey is to learn how to discern who is a scoundrel in the tavern—and who is truly a saint in the church.

This canto opens with Dante describing the crowd of devils escorting them through this bolgia as ‘strange’—mocking, treacherous, cruel, and utterly untrustworthy. Individually, they are comically terrifying; together, they radiate the same atmosphere of chaos and destruction as the scenes depicted in Brueghel’s The Triumph of Death.

The comedic brilliance of this canto lies in the pervasive mistrust—it’s not only between the devils and our companions, but among the devils themselves. It is worth keeping in mind that the only two characters in this canto who are united by trust are Dante and Virgil. The corrupt politicians and their infernal guards are united only by their vice; deceit and suspicion rule even their own ranks.

II. In the end, corruption devours itself

Perhaps the most comical—yet oddly sublime—moment in this canto is when Ciampolo, whom we’ll explore further in the Themes section, tricks the devils and escapes. In doing so, he creates just the distraction our companions need to make their own exit.

It is the first time we see a sinner outwit his own infernal guardians. The devils, terrifying as they seem at first, reveal themselves to be utterly incompetent. In the end, Ciampolo escapes, the devils fall into disarray, and some even tumble into the pit with the damned. Chaos unfolds. Were this scene not set in the depths of Inferno but on the surface of the Earth, it could well mark the beginning of a Triumph of Death.

What’s most striking, of course, is that Dante the author seems to suggest this is the only way to escape corrupt politicians: sooner or later, they will engineer their own downfall. And when that unraveling begins, the honest soul and upright reason must simply endure in silence—waiting patiently, while the devils turn on one another and choke on their own vice.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Pilgrim’s Progress, Rake’s Progress

My mother, who had had me by a wastrel,

destroyer of himself and his possessions,

had placed me in the service of a lord.Then I was in the household of the worthy

King Thibault; there I started taking graft;

with this heat I pay reckoning for that.

Barroliniano’s commentary explores the fact that Ciampolo interestingly begins telling his story by telling of his origins. The life of Ciampolo’s father is a veritable rake’s progress, as he proceeds from dissipation of his possessions to destruction of his own self, from squandering to suicide: he is, in his son’s words, “distruggitor di sé e di sue cose” (destroyer of himself and of his possessions [Inf. 22.51]).4

Ciampolo, in contrast, rose through the ranks and became a servant at the court, but he was born in the environment of dismisura (of not being able to measure, find balance when it came to riches.) He was not poor but did not know the bounds.

This echoes Aristotle’s notion of the ‘mean’—the ability to measure and balance all aspects of life. For instance, too much courage becomes recklessness, while too little is cowardice. It is the task of a virtuous person to discern the right balance between confidence and fear in any given situation. When he succeeds in finding that proper measure, he is called courageous.

Ciampolo was the continuation of his father’s downfall. His father, though not a poor man, brought ruin upon himself and his possessions—inflicting harm not only on himself but on his family as well. Ciampolo, whom we meet in the Inferno, followed that path of ruin by introducing the same destructive tendencies into his courtly position through corruption.

In other words, Ciampolo’s life mirrors a reverse of the pilgrim’s progress: where Dante rises from modesty to greatness, Ciampolo descends from wealth into disgrace.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

Of course the quote:

Noi andavam con li diece demoni.

Ahi fiera compagnia! ma ne la chiesa

coi santi, e in taverna coi ghiottoni.…

We made our way together with ten demons:

ah, what ferocious company! And yet

“in church with saints, with rotters in the tavern.”

It is a phrase I will remind myself almost daily. But I would like to share this thought by Aristotle which I believe accompanies the quote above well:

“Anybody can become angry — that is easy, but to be angry with the right person and to the right degree and at the right time and for the right purpose, and in the right way — that is not within everybody's power and is not easy.”

In Church with saints, with rotters in the tavern. It is a task of our mind to do the right thing, to the right degree, at the right time, for the right purpose and in the right way.

Sayers Hell 211

Singleton Commentary on Inferno 382

Singleton 383

https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/inferno/inferno-22/

These essays are always so rich. In this one, closing with the Aristotle quote was brilliant: “Anybody can become angry — that is easy, but to be angry with the right person and to the right degree and at the right time and for the right purpose, and in the right way — that is not within everybody's power and is not easy.”

Yes, yes, and yes to painting-read-alongs! Brueghel the Elder is the first painter whose paintings I fell in love with, who opened the door for me into the world of art. Because of this he will always have a special spot in my heart. Currently I’m also working through Aristotle’s Ethics so it was a pleasant surprise to see him here too! I have fallen off the read along a little but I’m catching up now 😃