Medusa and the Mind: What Dante’s Furies Teach Us About Despair

(Inferno, Canto IX): Furies and Medusa. Angel opens the gate with a wand. Heretics.

As long as you dwell on the past,

you’re filled with doubt and sorrow.

As long as you trust in yourself,

then you trust in tomorrow.

~ From Nietzsche’s The Joyous Science

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

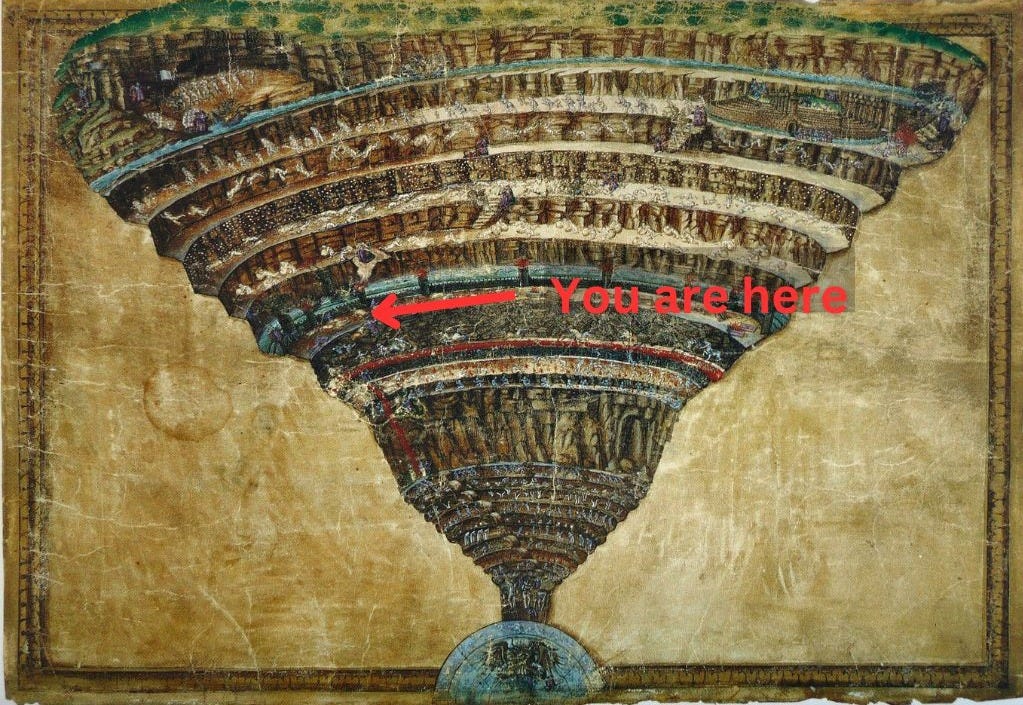

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Ninth Canto we find ourselves confronting the Furies. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Dante and Virgil stand outside the Gate of Dis - Dante learns that Virgil had been here before - The Furies and the threat of Medusa - A great wind storm announces a heavenly messenger - The messenger opens the gates of Dis with a rebuke to the fallen Angels - Dante and Virgil enter the gate - The plain of the burning sepulchers - The Arch Heretics

Canto IX: Summary

Dante pales as Virgil is pushed back from the Gate of Dis, as we saw at the end of Canto VIII. Virgil has a moment of doubt - ‘we have to win this battle…if not…’ (IX.7-8) - which grew into the firmness of knowing what to do in the assurance of guidance from above: “but one so great had offered aid. / That help seems slow in coming: I must wait!” (IX.8-9). This ‘one so great’ is Beatrice.

Dante asks if any from Limbo, those “whose only punishment is crippled hope” (IX.17), ever came down this far into Hell. Virgil says he himself has made the journey before.

He was called by Erichtho, a ghastly witch found in Lucan’s Bello Civili (Civil War), to do a mission into the deepest Hell - the circle of Judas - to bring a soul back to her when Virgil had been only shortly in Hell. Virgil’s trip below mirrors that of the Sibyl in the Aeneid, who tells Aeneas that she had been there in the depths of the Underworld before.1 The circle containing Judas is as far as is possible from the Primum Mobile, the highest level of the revolving Heavens before the fixed stars, and is therefore the soul most removed from the goodness of God.

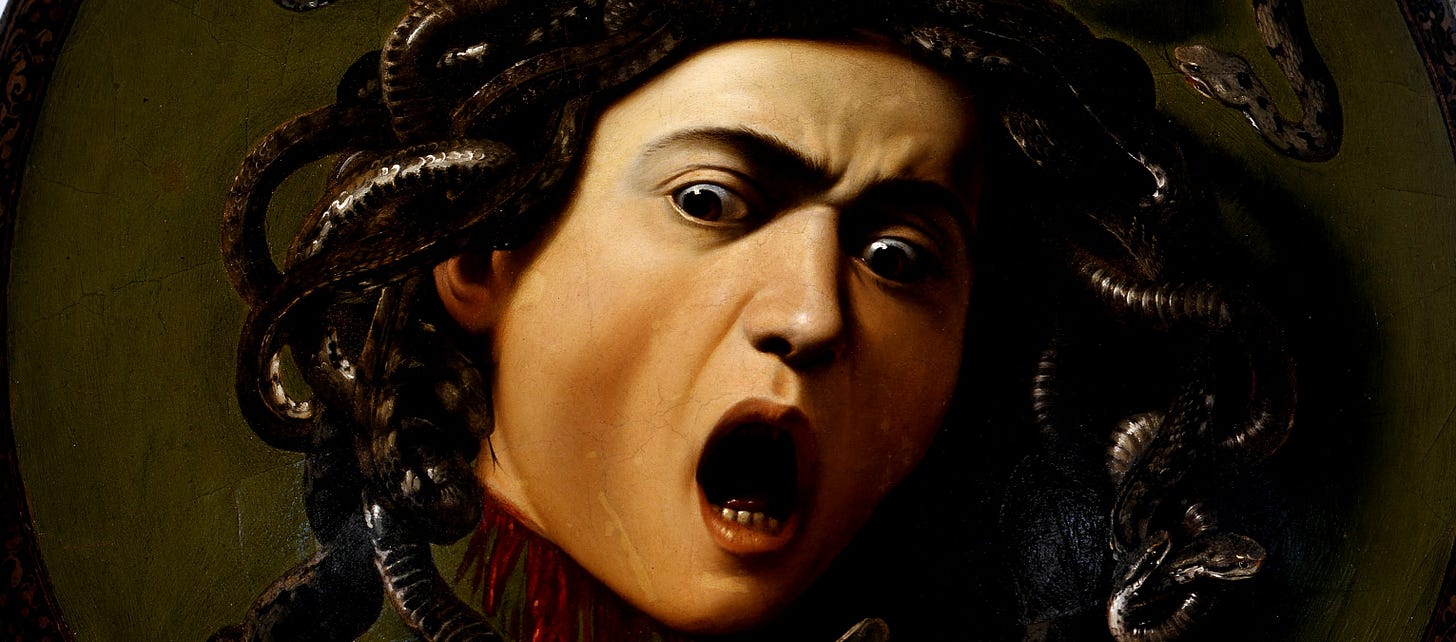

As Virgil speaks, Dante sees the light and flame at the top of the tower, which suddenly become the image of three Furies, or Erinyes in the Greek, who serve Proserpina, the Queen of Hell. The Furies are monstrous women flecked with blood, with coiled snakes as belts and hair. They are the embodiment of vengeance. Megaera, Allecto, and Tisiphone approached them, wailing and beating themselves.

They jeer that should Medusa arrive, Dante will be turned to stone. The stone that she threatens is that of despair which “so hardens the heart that it becomes powerless to repent.”2 Just as Theseus had made a previous journey to the Underworld while living to steal Persephone for his friend Pirithous, they point to that past error of not keeping him captive and think that they should not let Dante go.

Virgil warns Dante of the dangers of Medusa, and to avert his gaze. Here is one of those moments in which Virgil protects Dante:

He himself turned me

around and, not content with just my hands,

used his as well to cover up my eyes

IX.58

And here, a favorite, when Dante encourages us to look deeper into the symbolism of the moment:

O you possessed of sturdy intellects,

observe the teaching that is hidden here

beneath the veil of verses so obscure3

IX.60-63

Across the dark waves of the marsh they hear a terrible sound, as in a cyclone breaking down everything before it. Virgil guides him to look toward the sound, and they see the damned fleeing before it:

As frogs confronted by their enemy,

the snake, will scatter underwater till

each hunches in a heap along the bottom,

so did the thousand ruined souls I saw

take flight before a figure crossing Styx

who walked as if on land and with dry soles

IX.76-81

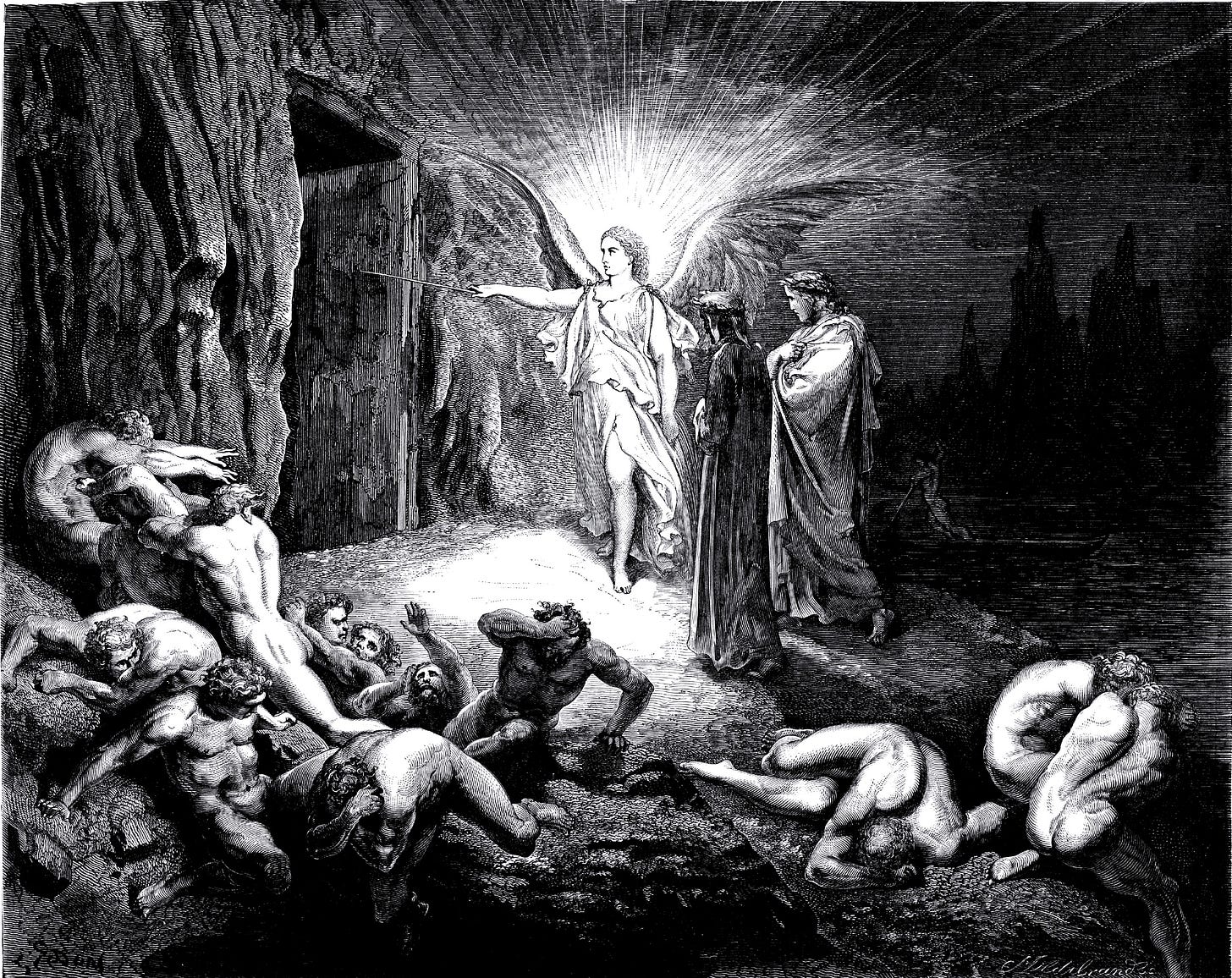

This Heavenly Messenger cleared the mist and fog from before himself as he walked, and Virgil signals to Dante to bow before him, who represents the grace that opens the way.

The gate of Dis swings open with just a wave of his wand. He calls to those within the walls, admonishing them for daring to go against God’s will even now, even in punishment in Hell, knowing the folly of it, the purposelessness of resistance. He reminds them of the time that Cerberus was punished for this very act, from which he had “both his throat and chin stripped clean” (IX.99) in the action of Hercules dragging him by the chain.

At this the messenger turns and leaves, already focused on his next task. Dante and Virgil were safe to enter the mighty city of Dis.

Dante had not known what they would encounter within the walls, and as they pass through the gate, there is a plain spread out before them, full of “lamentation and atrocious pain” (IX.111).

He sees before him in the plain many sepulchers, and in comparing them to the famous burial grounds - such as the Arles, and the Pola - describes the uneven landscape they create.

These sepulchers in Hell are aflame, and with the tilted lids, the cries of those burning within is heard. Dante asks who these sinners are, and is told they are arch-heretics and their followers. The fact that like is entombed with like at different levels of fire, refers to the gravity of higher or lower degrees of offense.

Dante and Virgil walk on between the sepulchers and the city walls.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

He who learns must suffer.

And even in our sleep pain that cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, and in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom to us by the awful grace of God.

~ Aeschylus

How does one flee from despair? Can a man be lifted if he refuses to rise? No force can stir the unwilling soul, nor can reason heal one who clings to his own ruin. When one finds oneself in a state of intense emotional illness, only a higher goal, purpose, or power can lift them out.

Before the gates of Dis, Dante and Virgil face grave danger of this kind—Dante, pale with fear; his guide, flushed with fury.

Virgil’s Doubt

“We have to win this battle,” he began,

“if not. . . But one so great had offered help.

How slow that someone’s coming to see me!”

At the start of this canto, Virgil is not consumed by fear, but by doubt. He cannot overcome the Furies, yet he knows that Divine power—Beatrice herself—has assured him that this journey is willed from above. And yet, for a moment, he wavers: ‘How slow that someone’s coming to see me.’ Impatience, anger, and uncertainty creep in, as if he briefly questions whether divine aid will arrive at all.

He knows the path, he knows his destination—the obstacle is not navigation, but the faltering of will. This is when reason turns against us—when we justify sin because we can no longer cast it off. This is when we lose the good of intellect and turn to stone.

The three Furies each embody a form of despair: Megaera, the festering wound of self-destructive envy; Alecto, the unrelenting fire of all-consuming rage; and Tisiphone, the most dreadful of the three, the spirit of vengeful destruction—the eternal torment that guilt and remorse inflict upon the soul. Furies are also seen as sin itself, representing three main categories of sin that we are going to encounter from now on - incontinence, violence, and fraud.

‘If the Furies represent remorse’ writes Dante scholar Barbara Reynolds ‘Medusa is despair. Virgil protects him with all that he represents of wisdom, art and civilisation.’4

Perhaps one of the most powerful moments in our journey thus far is this - Dante covering his eyes with his hands then Virgil, in turn, covering them with his own. Medusa, the monster that turns everyone who gazes at her into stone, symbolises despair, despair that halts life itself, despair that leads to self-destruction. Perseus slew this former priestess of Athena only by means of reflection through his shield.

I have always thought that Medusa also represents death itself, and looking at death straight into the face can cause the highest form of despair, but myth of Perseus tells us that certain creatures, like Medusa, can be overcome and understood only through reflection.

The whole scene is a battlefield!

This entire scene reminds me of a cinematic battle between the forces of good and evil. Dante and Virgil disembark in front of an unvanquishable fortress that they must conquer to survive. Its gates are sealed, the signals of an approaching enemy are sent from within, furies thrust into attack and get a stalemate when they face Virgil. They say that they have a secret weapon, Medusa, that they are going to deploy. In the meantime, forces of good have their own plan, their own secret weapon that will change the course of the battle.

Finally, after Dante survives the gaze of Medusa, the secret weapon of the good arrives, and thrust the gates of the impenetrable castle wide open for the forces of good to enter.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Themes 🖼️ :

Sturdy intellects (or, Dante addressing us)

O you possessed of sturdy intellects,

observe the teaching that is hidden here

beneath the veil of verses so obscure.

We perceive and comprehend this world through multiple means. Nature, after all, has given us five senses so we can not only see and smell but touch, taste and hear it.

We are also given reason but it in itself also has its limits and I do believe that Dante calls on his readers to increase our other senses, senses of feeling, allegorical interpretation, anagogical and moral.

Virgil’s Anger

This swamp that breeds and breathes the giant stench

surrounds the city of the sorrowing,

which now we cannot enter without anger.

Much debate surrounds the use of the word ‘anger’ (ira) in this passage. Virgil must be speaking of a different kind of wrath—not the wrath of sinners, but the wrath of God. A wrath that restores harmony, that sets all things back in order.

What it means to be a heretic

What astonishes me, of course, is how comprehensible—how just—the placement of sinners in Dante’s Inferno appears. Here, among the heretics, we do not find those who were merely ignorant of the divine, but those who deliberately forged sects and constructed entire systems of thought in defiance of God.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

O you possessed of sturdy intellects,

observe the teaching that is hidden here

beneath the veil of verses so obscure.

Characters:

- Erichtho - Erichtho is a witch who lives among the dead; In Lucan’s Bello Civili, Pompey’s son Sextus visits Erichtho for a prophecy to learn the outcome of the battle of Pharsalia against Julius Caesar. The scene of necromancy is one of the more graphic scenes in the literature of antiquity, and also includes Hecate and the Furies. Here is an excerpt:

These rites of wickedness, these crimes of savage race

beastly Erichtho had condemned for their excessive holiness

and had applied her filthy skill to unknown rites.

For her it is wrong to rest her deathly head

beneath a city's roof or home, so in abandoned tombs she lives

and, driving out the ghosts, is mistress of the graves, the darling

of the gods of Erebus. To hear the meetings of the silent dead,

to know the Stygian homes and mysteries of hidden Dis

is not prevented by the gods or life. The blasphemer's face

is gaunt and loathsome with decay: unknown to cloudless sky

and terrifying, by Stygian pallor it is tainted,

matted with uncombed hair: if rain and black

clouds obscure the stars, then out comes the Thessalian woman

from bare tombs and catches at night's thunderbolts.

Bello Civili VI.507-520

- Judas - The betrayer of Jesus that led to his crucifixion, Judas is housed in the very deepest level of Hell (Inferno XXXIV.62-63).

- Furies - Erinyes - the three Furies are goddesses of vengeance in Greek mythology. They are called Erinyes in Greek, and in the play Eumenidies by Aeschylus they serve a role that turns them into the the Kindly Ones after the trial of Orestes for the slaying of his mother Clytemnestra. Virgil placed Tisiphone outside the gates of Tartarus in his Underworld (Aeneid VI.555).

- Proserpina - The Queen of Hell is known as Persephone, Proserpina or Hecate.

- Medusa - The vengeful goddess whose glance turns to stone. She was the youngest sister of the Gorgons, and was cursed by Minerva (Athena) with snake for hair and a deadly gaze after being assaulted by Neptune in Athena’s temple, thus defiling it.

- Theseus - One of the adventures of the Greek hero Theseus is that in which he and his friend Pirithous both decided to marry daughters of Zeus. Theseus kidnapped Helen (later of Trojan War fame) for himself, after which the two friends traveled to the Underworld to kidnap Proserpina for Pirithous. They were captured, and there are various accounts of the results.

And when they had at last made their way below to the regions of Hades, it came to pass that because of the impiety of their act they were both put in chains, and although Theseus was later let go by reason of the favour with which Heracles regarded him, Peirithoüs because of the impiety remained in Hades, enduring everlasting punishment; but some writers of myths say that both of them never returned.

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4.63.4

Aeneid VI.564-65

Sayers Hell 127

Dante speaks of the four levels of interpretation of his work in the Letter to Cangrande.

Barbara Reynolds, Dante, page 143

My favorite action-packed canto! The arrival of the “Heavenly Messenger” brings to mind the poem “The Campaign,” by Joseph Addison, commemorating the English and Austrian victory in 1704 over the French at the Battle of Blenheim, and the Duke Of Marlborough’s military genius:

“So when an Angel, by Divine Command,

With rising Tempests shakes a guilty Land,

Such as of late o'er pale Britannia past,

Calm and Serene he drives the furious Blast;

And pleas'd th' Almighty's Orders to perform,

Rides in the Whirl-wind, and directs the Storm.“

As Vashik and Lisa note, some commentators actually describe IX as reminiscent of a military campaign. The two distinct halves of this canto, at least to me, reflect the anxiety before the start of a battle, and the intense relief that comes when your enemies are dispatched with ease. The first half is tension-laden, with uncertainty, doubt, and fearful anticipation of what might happen. Reason itself is baffled and disabled; Dante and Virgil are all but paralyzed. (The famous hunter Jim Corbett said “The word 'terror' is so generally and universally used in connection with everyday trivial matters that it is apt to fail to convey, when intended to do so, its real meaning.”) The only hope is to bank on, and wait nervously for God’s intercession. And that makes the canto’s second half all the more astonishing — witnessing unmatched power wielded to handily dismiss what ignited their fears. In his notes to IX, John D. Sinclair says: “It is the representation in naked simplicity of the victory of divine omnipotence over diabolical insolence.”

Perhaps Seneca best summed up the overall experience of the pilgrim and guide in this canto: “We suffer more often in imagination than in reality.”

IX, to me, is a confrontation between two systems of instincts — the demons, animalistic, with permanent fear and alertness as their occupation, versus Dante (“everyman”) and Virgil (“reason”), who, reason having failed, and lacking the honed instincts of the animal, instinctively turn to that forward-leaning virtue — hope — for divine intervention.

Now to hazard some armchair psychoanalysis — I am convinced we see Dante’s military experience subtly reflected here, and will more directly in subsequent cantos. (Dante took part as a cavalryman at the fierce Battle of Campaldino in June 1289, and at the siege of Caprona in August of that year). Veterans will recognize the moments when Dante instantly reverts to the ancient strands of his DNA in the face of imminent danger. Only someone, I think, that has similar military experience would fully appreciate the Paleolithic depth of the his emotions. He is understandably fearful, but also (IMHO) demonstrates a hard-earned, calculated sense of the menace he faces. (In Barbara Reynold’s “Dante: The Poet, The Thinker, The Man” she notes: “In a letter which Bruni saw, he [Dante] described the battle [Campaldino] and drew a plan of it, saying that though he was then no novice in arms he at first felt great fear, which changed to exultation when the cavalry, routed in the beginning, regrouped and charged, defeating the enemy.”) He isn’t panicked here, if we understand panic to be “flight” driven by overwhelming fear in order to secure safety — although he certainly contemplates retreating! Dante’s anxiety reminds me of an apt quote from a Confederate infantryman at Gettysburg, waiting for his part in Pickett’s Charge: “When a rabbit darted out of some bushes and made a dash for the rear, one man apparently called out, “Run, old hare,” confessing, “If I was an old hare, I’d run too.” Yet Dante doesn’t run.

Here’s a weird tangent with respect to Medusa: I couldn’t help but think of a curious juxtaposition between Dante’s “Rime Petrose” (stony rhymes) and the threatened appearance of Medusa. He wrote four early lyrical poems that celebrate his unrequited love for an unnamed lady — his “donna di petra” (woman of stone). He compared her emotional coldness and unattainability to stone, and suffered intensely from frustrated love. Contrast that with the repellant Medusa, who threatens to turn him into stone!

Speaking of repellent figures: Dante exercises some extraordinary literary gymnastics with his incorporation of Erichtho, as Vashik and Lisa point out. He creates a fantastical narrative where she, a mortal witch, is vested with powers normally reserved for divine or demonic forces, and dispatches Virgil to retrieve a soul from the deepest part of Hell. Who gets retrieved is unstated — but we can be sure it wasn’t a petty criminal. This anecdote may well be Dante reminding us of Virgil's limitations as a pagan. Virgil is not immune to the influence of dark forces, and his knowledge of Hell is partly derived from his service to a figure of evil. If I was Dante and Virgil told me “I know the way; be sure of that,” and then said Erichtho was his travel agent, I might question my choice of guides.

P.S. Did I say that heavenly messenger is freaking awesome? Dante’s terse but evocative description reminds me of a line from the poem “The Rock and the Hawk” by Robinson Jeffers:

“…bright power, dark peace;

Fierce consciousness joined with final

Disinterestedness…”

Thank you for teaching us, and the art.