Michelangelo and Dante: Sculpting and Singing the Divine

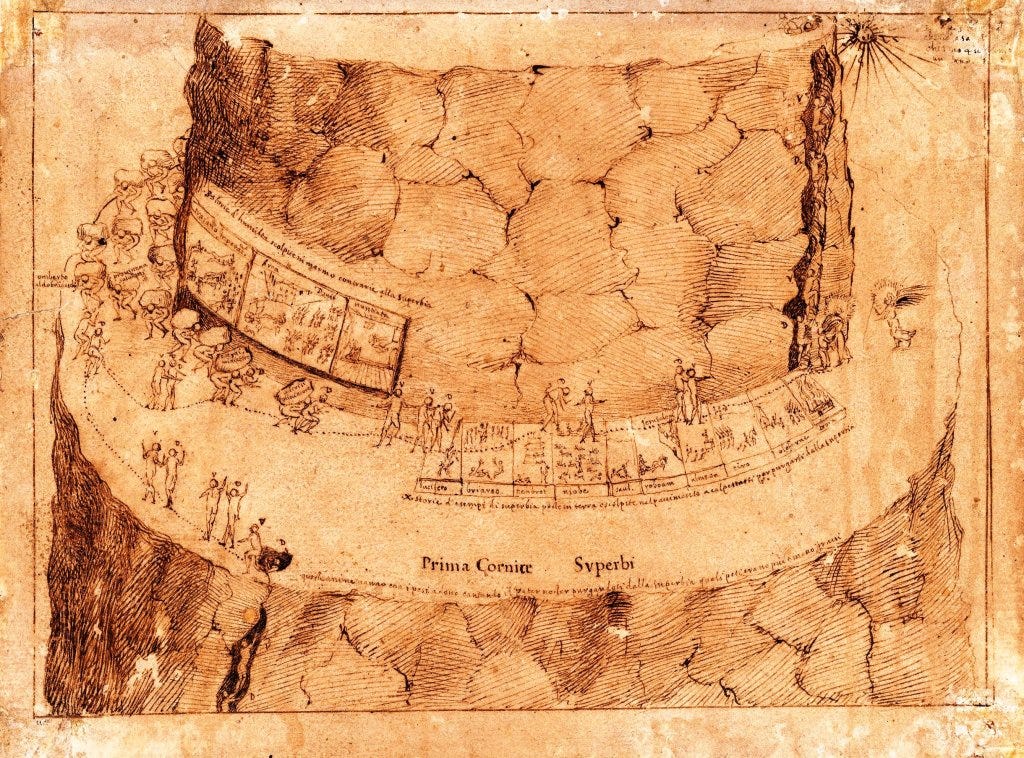

(Purgatorio, Canto X): First terrace, Prideful, Carvings on the Rocks

“The greatest danger for most of us is not that our aim is too high and we miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it.”

~ Michelangelo

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Tenth Canto of the Purgatorio, we arrive in the first terrace. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

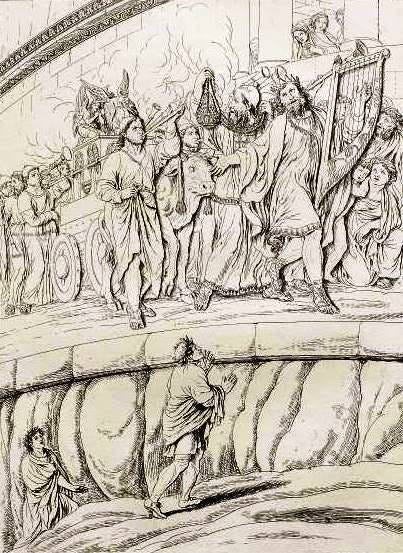

The first terrace of Purgatory - The needle’s eye - A vast, deserted path - The marble cliff and the lifelike carvings - The annunciation and Virgin Mary, the Ark of the Covenant, the dancing King David, the Emperor Trajan - the Prideful penitents, weighed down by stones.

Canto X Summary:

The boundary into Purgatory has been crossed, and Dante and Virgil - and we along with them - enter a new realm; the first cornice, or terrace of Purgatory. Slowly their journey has brought them further and further from the stain of the sins of Hell, away from those whose “aberrant love would make / the crooked way seem straight” (2-3).

This is lower Purgatory, consisting of the first three terraces; if we take our view through the idea of the ordered versus disordered loves of St. Augustine—ordo amoris—and if those in the Inferno loved the wrong thing, here, in this first terrace, we can consider it, in the words of translator and commentator Dorothy Sayers, ‘love perverted’, namely “love of self perverted to hatred and contempt for one’s neighbor”,1 which translates into Pride.

For though it be good, it may be loved with an evil as well as with a good love: it is loved rightly when it is loved ordinately; evilly when inordinately…we do well to love that which, when we love it, makes us live well and virtuously…a brief but true definition of virtue to say, it is the order of love.

St. Augustine, City of God

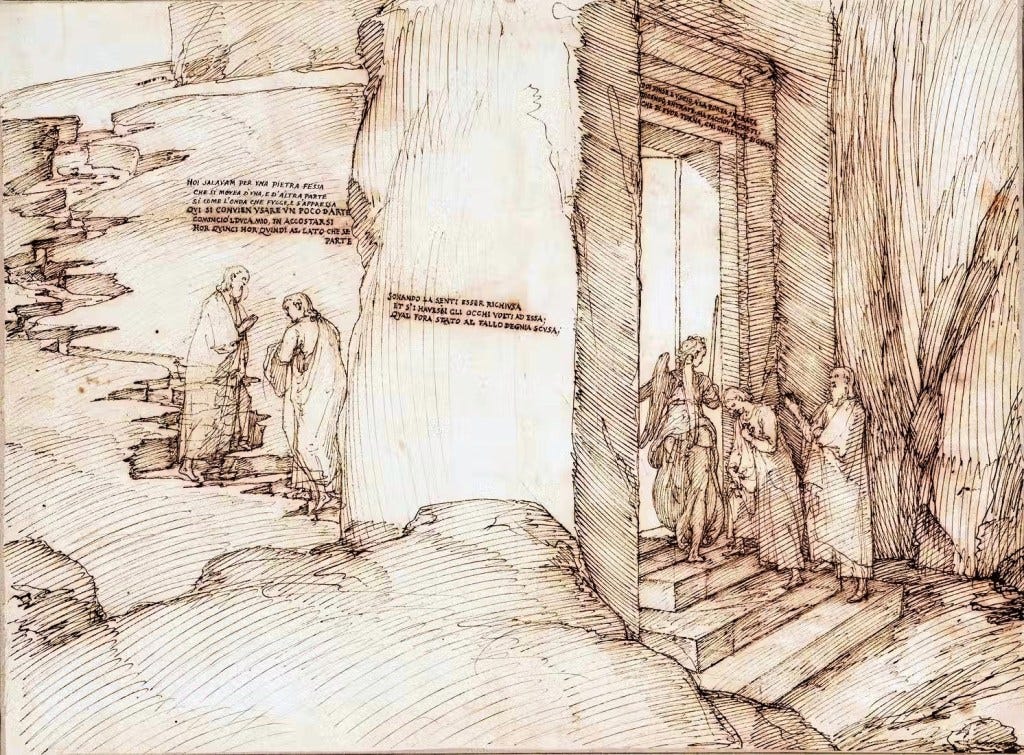

As the gate closed behind them, it resounded with a tenor that proved the infrequency of its use. Dante regarded the message of the guardian angel at the gate to not look back; an action which, through having been warned, would be worthy of no excuse if broken. They made their way through the steep clefts of rock, challenged at every step, until as the moon set, they made it through the “needle’s eye” (16).

It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.

Matthew 19:24

Once they had passed through the narrow way into the open, how deserted it seemed! The broad path—the width of three bodies laid head to foot—was clear and empty, notable for its spaciousness compared to the crowded throngs of hell. This is truly a new landscape, new to them both, for neither knew what sights they would encounter as they progressed.

As if to welcome them, a cliff of white marble, rising high into the air and covered with carvings, met their eyes; carvings so divine that even the works of Polycletus, the greatest sculptor of the ages, would pale before them; even the beauty of Nature herself could not compare.

Polycletus was a celebrated Greek sculptor, a contemporary of Phidias, but somewhat younger. He was supposed to be unsurpassed in carving images of men, as Phidias was in making those of gods, and is so acclaimed by Cicero, Pliny, Quintilian, and others.2

We attribute ‘wisdom’ to the most certain arts; accordingly we call Phidias a wise sculptor, and Polycletus a wise statuary. Here then by wisdom we mean nothing more than the excellence of the art.

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics

Before the theme of this terrace became clear to the pilgrim and the poet, they encounter an example of that virtue which is its opposite; here, the figures carved into the marble are examples of perfect humility.

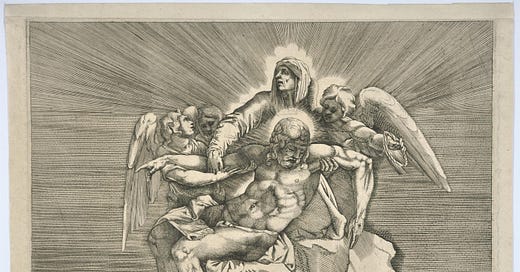

The angel who reached earth with the decree

of that peace, which, for many years, had been

invoked with tears, the peace that opened Heaven

after long interdict, appeared before us,

his gracious action carved with such precision -

he did not seem to be a silent image.

x.34-39

The angel Gabriel, his image practically singing from the marble, invoked the scene from the Annunciation, in which Mary was visited by him to give her the news of her role as the mother of God, the words Ecce ancilla Dei—behold the handmaid of God—marking her scene in the marble.

This intaglio initiates what will prove to be a constant pattern in Purgatory, i.e., Mary always comes first in the series of virtues and in this way is proclaimed to be the keystone of them all.3

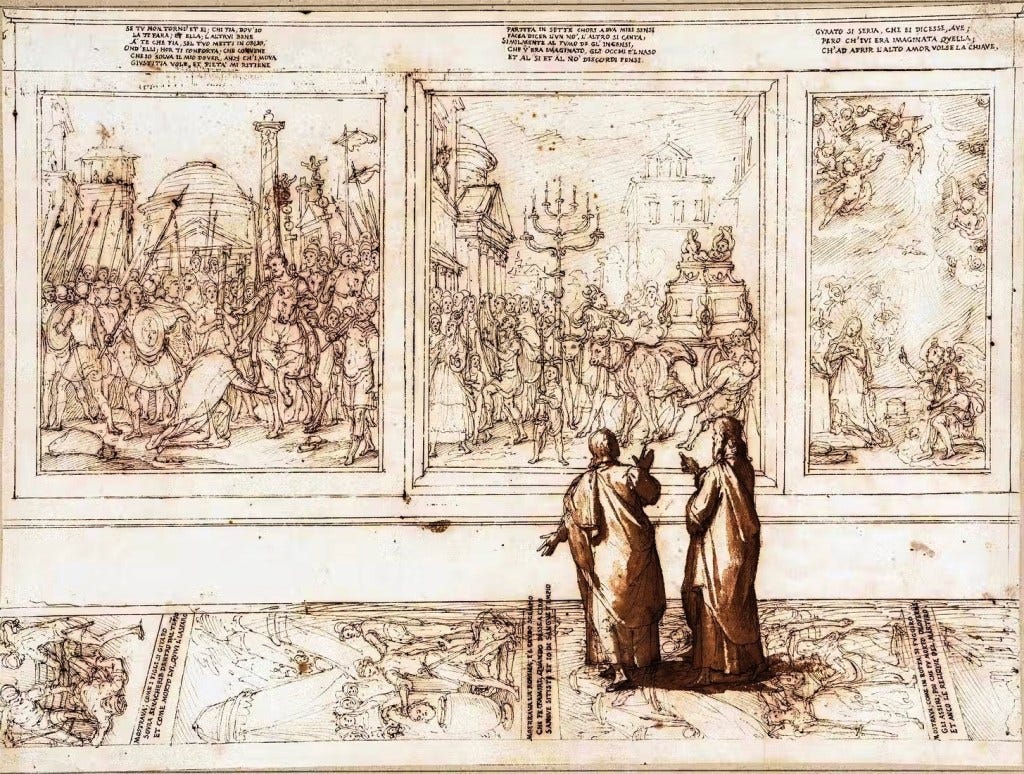

The carvings continued along the marble cliff, as Virgil guided Dante to the relief of the Ark of the Covenant—the sacred chest which held the ten commandments of Moses—which was imbued with such holiness that all were commanded to touch it not, lest they be struck down dead. Uzzah, in guiding the path of the ark, put out his hand to stop its fall after the oxen carrying it faltered, and was cast dead at the moment. His example “makes men now fear tasks not in their charge” (57); even with the good intention, it was not his place to touch it, but only the place of a high priest.

And when they came to Nachon's threshing floor, Uzzah put forth his hand to the ark of God, and took hold of it; for the oxen shook it. And the anger of the Lord was kindled against Uzzah; and God smote him there for his error; and there he died by the ark of God.

2 Samuel 6:6-7

So lifelike were these images, that Dante’s senses were affected just as if he were encountering a living thing; he heard, saw, and even smelled the marble scene:

People were shown in front; and all that group,

divided into seven choirs, made

two of my senses speak-one sense said, “No,”

the other said, “Yes, they do sing”; just so,

about the incense smoke shown there, my nose

and eyes contended, too, with yes and no.

x.58-63

As the scene of the Ark continued, King David of Israel danced with joy at it’s progression through the city, “both less and more than king” (66); less for the undignified action of lifting his robe in dance, more for his humility in discarding all pretense of rank to express his joyous heart. Watching from the side with scorn was his wife Michal, shamed at his actions, but that shame did not detract him even when she spoke to him with malice:

And Michal the daughter of Saul came out to meet David, and said, How glorious was the king of Israel today, who uncovered himself today in the eyes of the handmaids of his servants, as one of the vain fellows shamelessly uncovereth himself! And David said unto Michal, It was before the Lord, which chose me before thy father, and before all his house, to appoint me ruler over the people of the Lord, over Israel: therefore will I play before the Lord.

2 Samuel 6:20-21

The final tale of humility recounted that of the Roman Emperor Trajan in the moment he was leaving for war; he heeded the plea of a widow whose son had been murdered and was asking for justice; rather than put her off, he honored her request with a humble spirit, acting as a leader who honors the most lowly citizen. There is a legend about Trajan, “whose worth had urged / on Gregory to his great victory” (74-75):

Gregory I, the saint, called Gregory the Great, was born at Rome, of a noble family, and was pope from 590 to 604. The legend, alluded to by Dante, that the Emperor Trajan was recalled to life from Hell, through the intercession of Gregory the Great, in order that he might have room for repentance, was widely believed in the Middle Ages and is repeatedly recounted by medieval writers. Thomas Aquinas, who cites this case of Gregory’s intercession for Trajan, attempts to reconcile it with the orthodox doctrine that prayer is of no avail for those in Hell in his Summa Theologica.4

This was the speech made visible by One

within whose sight no thing is new-but we,

who lack its likeness here, find novelty.

x.94-6

So miraculous were these carvings, made by God, that it was as if Dante audibly heard the whole conversation between Trajan and the widow; such perfection of form is not even possible on earth.

As Dante absorbed these amazing sights, the souls residing in the first terrace made themselves known; their sin, the one they are working through, is in contrast to the humble figures in relief; they are the Proud.

But I would

not have you, reader, be deflected from

your good resolve by hearing from me now

how God would have us pay the debt we owe.

Don’t dwell upon the form of punishment:

consider what comes after that; at worst

it cannot last beyond the final Judgment.

x.102-108

Recall that the debts being paid in Purgatory are repaid joyfully, with the knowledge of their expiation and eventual cleansing; while those in Hell are doomed to an eternal punishment, here, it is only temporary. At the Last Judgment all will be reconciled.

In any case the punishment will cease at the Judgment Day, for then the purgations of Purgatory will stop, and all the souls there, even as souls in Hell, will return for their bodies and hear the judgment, “that which resounds to all eternity”; but souls who happen to be in Purgatory at the time will proceed to their reward in Heaven, of course, and those of Hell will return to their eternal punishment there. 5

Dante did not understand what he saw as the souls approached; so bent were their bodies under the giant, heavy stones they carried that they were unrecognizable at first sight as human forms. Underneath these stones they made their slow way forward, beating their breasts, perhaps in that same attitude of mea culpa, claiming the responsibility for their fault.

O Christians, arrogant, exhausted, wretched,

whose intellects are sick and cannot see,

who place your confidence in backward steps,

do you not know that we are worms and born

to form the angelic butterfly that soars,

without defenses, to confront His judgment?

Why does your mind presume to flight when you

are still like the imperfect grub, the worm

before it has attained its final form?

x.121-129

Even in their willingness to transform, the challenge was so intense, that Dante saw in one of their eyes, even the most patient one, the struggle to continue, almost unable to go on.

💭 Philosophical Exercises

“Beauty is the purgation of superfluities.”

~ Michelangelo

In her magnificent work The Greek Way, Edith Hamilton helped me understand the truth behind what makes a work of art truly great.

For years, I have walked through the doors of the National Gallery in London and have been struck by the beauty of the masterpieces on display. I didn’t even need to look at them directly to feel their power—their beauty seemed to act upon my spirit and mind from a distance.

I know that Stendhal’s syndrome—a condition in which one might lose consciousness in the presence of overwhelming beauty—is real because I’ve experienced it. I did not faint in the heart of London and embarrass myself (ha!), but I felt that if I gave full rein to my emotions, I just might have.

Ever since my mind was illumined, since I began to truly see and feel curious about art—I’ve asked myself: Why does one masterpiece nearly make me lose consciousness, while another, hanging not far away in a different gallery, leaves me unmoved?

Why does one work of art, seen by millions each year, stir nothing in me—while another takes my breath away and leaves me transformed?

I ask this question, I hope, with humility. I’ve always found the remark “My five-year-old could have drawn this” to be rhetorically strong, yet philosophically shallow, for it doesn’t really address the heart of the matter.

Edith Hamilton’s chapter on “Mind and Spirit” in The Greek Way offered a light on this question. She observes that over two thousand years ago, in Ancient Greece, a rare and powerful union took place: a marriage between mind and spirit. And from this marriage, Western—or more broadly, European—art was born.

By contrasting civilizations, Hamilton shows that before this fusion occurred, art tended to take two distinct forms: on one hand, there was rigid, material art, which aimed to replicate reality as closely as possible—think of the documentary quality of cave paintings. On the other hand, particularly in the East, art was spiritual but formless—intense, unbounded, and unshaped, an outpouring of feeling without structure.

The result? In the first case, we get something akin to a poor photograph: a record, not a revelation. In the second, we find emotion without form—expressive, perhaps, but often chaotic and untethered.

The genius of the Ancient Greeks was that they brought these two together. For the Greeks, the spirit, which was limitless by nature, had to be disciplined and shaped, while the material world, with all its boundaries, had to be perfected and elevated.

Hamilton gives the example of a Greek sculptor who traveled to an island renowned for its beautiful women in order to sculpt Helen of Troy. But he did not choose one woman as his model. Instead, he observed them all and combined their finest features—creating an ideal, a harmonious image of beauty beyond any single individual. He shaped matter into the image of spiritual perfection.

And this, I believe, is at the very heart of our journey through Purgatory, and eventually into Paradise. The soul, limitless and divine, is confined within the finite material body. In the previous canto, the angel inscribed seven Ps onto Dante’s living forehead—a body still subject to time and corruption. It is a sign that we must treat our lives like the sculptor treats his marble: chiseling away what is superfluous, so that the form of the soul may shine through.

To return, briefly, to my original question: Why does some art stir my soul, while other pieces leave me numb? I believe the answer lies in what Hamilton revealed. Much of contemporary art suffers from the same two ailments: on the one hand, we see art reduced to lifeless documentation— for example, a soiled bed with used tissues, a photograph of what simply is; on the other, we see erratic brushstrokes without intention—an explosion of expression, but with no form, no feeling.

This, to me, is a testament to Hamilton’s insight. The bond between mind and spirit has fractured. Today, one is either a rigid materialist, or a formless fanatic.

A centuries ago however, there lived a sculptor who knew Dante’s Divine Comedy by heart, a sculptor who achieved the union of these two powerful forces - of mind and of spirit - more than any other artist - his name was Michelangelo Buonarotti.

I. The Art of Visible Speech

There we had yet to let our feet advance

when I discovered that the bordering bank—

less sheer than banks of other terraces—was of white marble and adorned with carvings

so accurate—not only Polycletus

but even Nature, there, would feel defeated.(lines 28 -33)

Lines 32–33 of Purgatorio Canto X have often been interpreted as Dante’s prophecy of the coming of a divine sculptor—one who would not only surpass Polycletus (the sculptor considered unsurpassable in Dante’s time), but who would even overcome Nature itself: “even Nature, there, would be defeated.”

Who did Dante mean?

Let the prophesied sculptor answer himself, for he was not just a sculptor, he was a poet too. The verses of this divine man are often neglected and overshadowed by his marble masterpieces:

From heaven he came down, and after sight

of both the hells, the just and merciful,

returned in mortal dress to gaze his fill

on God, then show us all in its true light.

A radiant star, that with his beams made bright

my undeserving birthplace, not the whole

bad world would be reward for such a soul.

You only, his creator, could be that.

I speak of Dante, for his works were least

valued by that ungrateful flock who failed

to shower favors only on the just.

If I were he, to have such fate at birth,

and with his virtue share his harsh exile,

I would exchange the happiest state on earth.

This is Sonnet 248 by Michelangelo Buonarroti, who admired the Divine Comedy so deeply that, according to his friend Ascanio Condivi, he “knew the whole of Dante’s masterpiece by heart.”

In 1518, Michelangelo even petitioned Pope Leo X for permission to construct a tomb for Dante in Florence at his own expense. The petition failed—Dante’s remains were in Ravenna, and they remain there still. In fact, it wasn’t until the 21st century that the Florentine authorities officially revoked Dante’s exile.

(Crazy, isn’t it?)

What moved me most in Michelangelo’s verses were the final three lines, where the great sculptor confesses that he would be willing to suffer as Dante did if only it meant he could possess Dante’s genius.

That thought absolutely stuns me. It leaves me in a kind of vertigo.

You’d think that if you were Michelangelo (arguably more widely known today than Dante) you had not only succeeded in life, but secured your place in eternity. After all, this is the man who painted the Sistine Chapel, whose very name has become synonymous with artistic perfection.

And yet, even Michelangelo longed to be Dante.

II. Michelangelo and Leonardo fighting over Dante

There’s a well-known story from Renaissance Florence: one day, Leonardo da Vinci was standing in the city centre, discussing verses from Dante with a group of friends. As he noticed his rival, Michelangelo, passing by, Leonardo called out mockingly: “Here comes the great Michelangelo, who knows Dante by heart! Surely he can help us interpret these lines!”

Sensing the sarcasm, Michelangelo snapped back. He dismissed both the conversation and Leonardo’s tone, making a sharp remark about Leonardo’s habit of leaving works unfinished, who had famously abandoned his grand project of the horse sculpture.

In that moment, it was not just a clash of egos, but of two towering artists, each invoking Dante as both a weapon and a mirror of their ambition.

Geniuses are always in conversation with other geniuses.

By this, I don’t only mean the visible rivalry between Leonardo and Michelangelo—I mean something deeper. Michelangelo was in conversation with Dante, just as Dante was in conversation with Virgil, as we have witnessed throughout our journey.

The reason I draw so much attention to Michelangelo in this canto is because I believe that, from this point onward, our journey takes on a new, prominent theme: the relationship between mind and spirit, as explored in Edith Hamilton’s The Greek Way, and the profound interrelation between poetry and sculpture.

Dante sculpts with words. Michelangelo, in turn, gives voice to the soul through stone. Both are engaged in the same sacred task: to reveal the invisible through the material—to give form to what lies beyond form.

III. Three Virtues

In this canto Dante enters the terrace of Purgatorio and as he ascends he sees three stories “sculpted” on the walls. I would dare to say that perhaps Dante experiences what I described as my experience as I enter through the doors of the National Gallery of London - in its much higher form. His sees a visible speech carved on the rocks: The Annunciation of Mary; King David Dances Before the Ark; and Emperor Trajan and the Widow.

I found this canto to be incredibly beautiful because Dante shows us the power of art. The power of art to cause inner transformation. Each of these scenes that Dante witnesses in Purgatory carries a purpose of transformation that one must undergo as they journey through there.

What does this mean—and can a secular person today draw a lesson from it?

Mary’s Annunciation is not an act of blind submission to God’s will. Rather, it is the inverse of Lucifer’s rebellion. Where Lucifer refused to serve, Mary consents freely—making her not only the reversal of the Fall, but also the beginning of redemption.

Just two cantos ago, we witnessed how Lucifer’s pride led humanity out of Paradise. Now, through Dante’s vision—so filled with beauty and grace—we are shown the path back. As we’ve discussed before, Mary is the reverse image of Eve: if Eve violated God’s command, Mary fulfills it through her willing “yes.”

But what does this mean to the secular mind?

It speaks not of submission to dogma, but of a deeper harmony—a refusal to rebel against the nature of things. It is the willingness to align oneself with something greater than ego: a truth, a purpose, a calling. Not a denial of freedom, but its fulfilment.

We are now on the terrace of the proud, and the image of King David dancing with joy reminds us of a profound truth: before Nature (or, God) all are equal.

To put it simply, whether you are a mighty king or a humble peasant, when the forces of Nature rise—be it storms, earthquakes, or time itself—no palace is more secure than a cottage. The king’s fortress is just as vulnerable as the farmer’s field.

Boethius, in The Consolation of Philosophy, would underscore this with the figure of Fortune whose wheel lifts some to heights of wealth and power, only to cast them down without warning. Pride, then, is not just a sin, it is a form of blindness to the fragile, shifting ground on which all human lives stand.

And finally, the scene of Trajan.

Many commentators rightly see this moment as a profound expression of compassion—a great emperor pausing to help someone far beneath him, someone in desperate need. And they are not wrong. But I would add one small nuance:

Compassion is not only care for others—it is also the open-mindedness to imagine how our own lives could have unfolded differently. It is the act of lifting ourselves out of the prison of our singular perspective and recognizing that our story might have taken another path—and still can.

As Joan Didion once wrote, “Life changes in the instant. The ordinary instant.”

I hope my reader will permit me to conclude this section under the heading of themes, as I have a few final reflections that naturally belong there.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. Prideful Carry Stones on Them

I’d like to draw your attention once again to the image of the prideful souls, bent beneath massive stones. If my reader will indulge a bit of speculation, perhaps these souls resemble those who refused to carve themselves out of the marble—unlike Michelangelo, who famously said he saw an angel trapped in the marble and carved it to set it free.

The prideful look at the bare block of marble that is their existence and say: “It’s beautiful just as it is—raw, formless, imperfect. Nothing needs to be removed.”

This, I believe, is the root issue with pride. It whispers, “You are fine as you are. Don’t change a thing. You are already perfect.” And in doing so, it halts the work of self-transformation.

II. Narrow entrance

Dante and Virgil have just entered Purgatory. The first thing Dante describes is the sound of the door closing behind them: a vivid, echoing sound that suggests how rarely this gate is opened. Those who are crooked often believe their path to be straight.

There’s also a striking parallel in the path itself: narrow as the eye of a needle. This sharply contrasts with the entrance to Hell, which was broad and wide—easy to enter, but hard to leave.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

O Christians, arrogant, exhausted, wretched,

whose intellects are sick and cannot see,

who place your confidence in backward steps,do you not know that we are worms and born

to form the angelic butterfly that soars,

without defenses, to confront His judgment?Why does your mind presume to flight when you

are still like the imperfect grub, the worm

before it has attained its final form?

Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory 67

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on Purgatorio 202

Singleton 203

Singleton 212

Singleton 216

Vashik, this was superb.