Oculus Tortus: The Twisted Eye

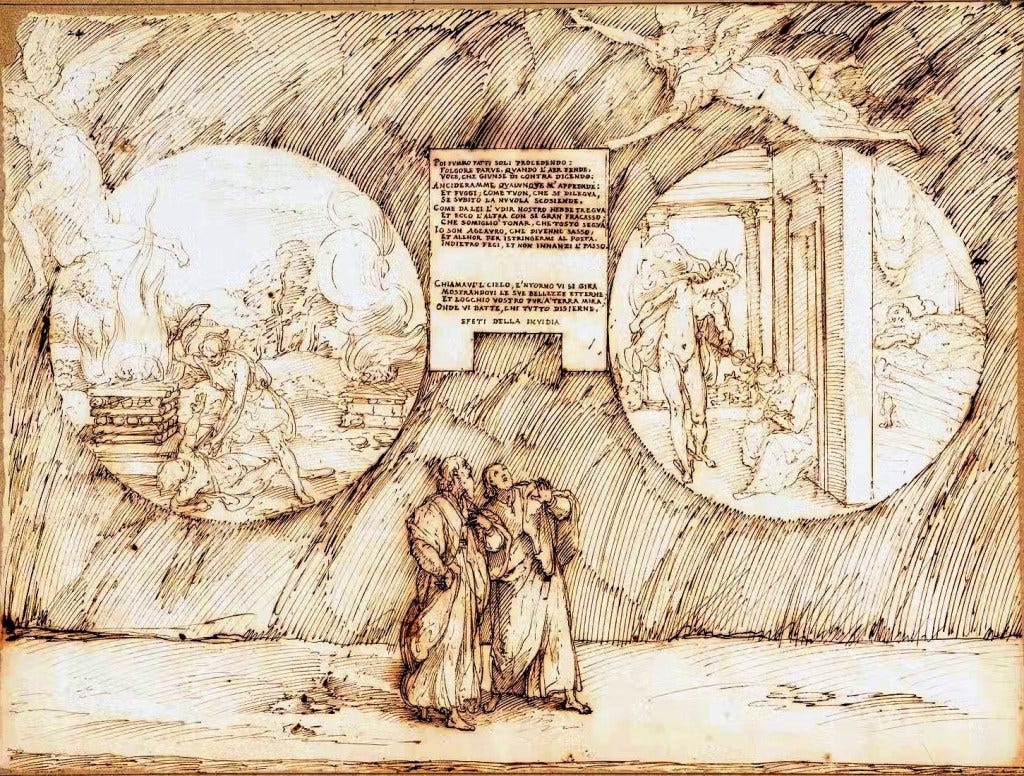

(Purgatorio, Canto XIV:) Reverse of the Book of Life, Guido, Rinieri

For as faintness is a disease of the body, so is vice a sickness of the mind. Wherefore, since we judge those that have corporal infirmities to be rather worthy of compassion than of hatred, much more are they to be pitied, and not abhorred, whose minds are oppressed with wickedness, the greatest malady that may be.

~ Boethius, Book IV

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

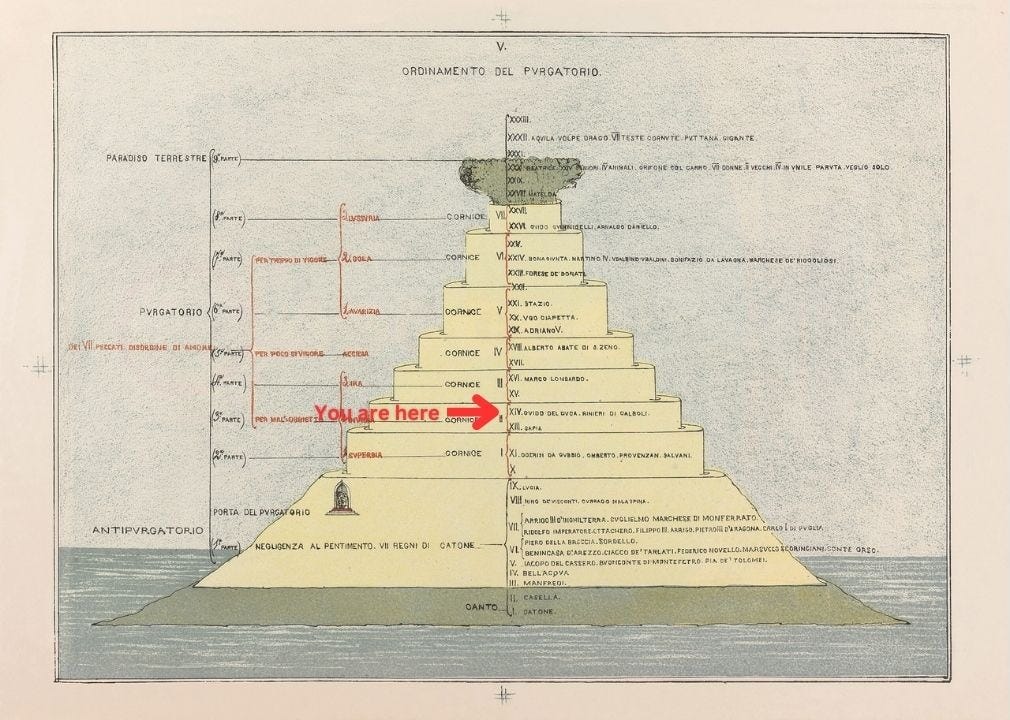

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Fourteenth Canto of the Purgatorio, we hear a lament upon Romagna. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

The second terrace of Envy, continued - Two souls Guido del Duca and Rinier da Calboli - The valley of the Arno - Guido’s lament of Romagna - Whip of Envy - Cain and Aglauros.

Canto XIV Summary:

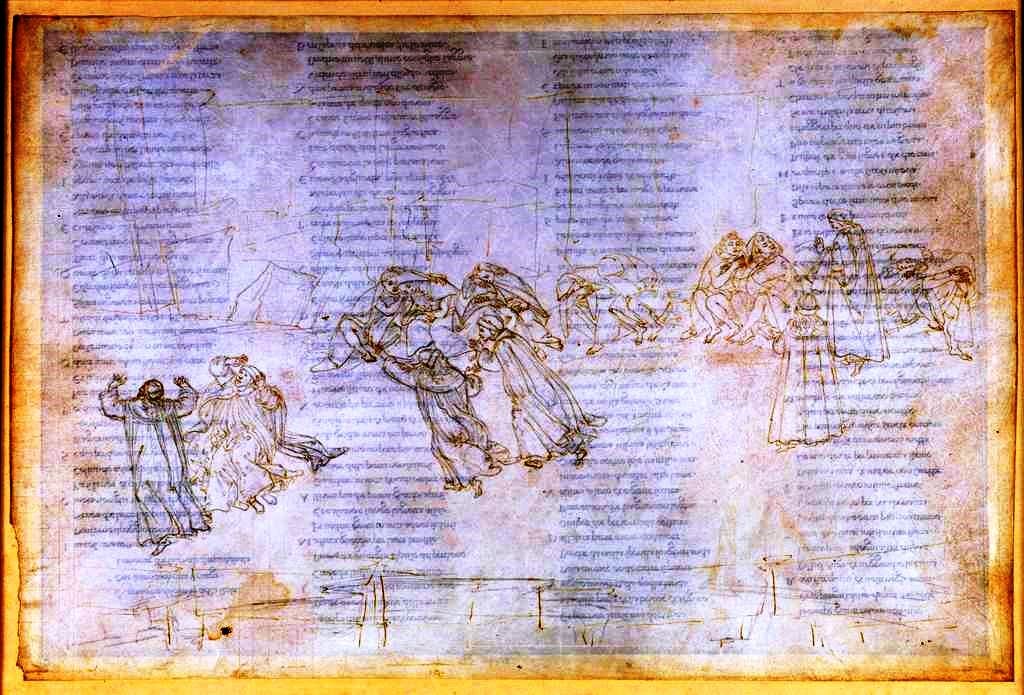

The voices of two penitents on the terrace of Envy spoke to each other concerning Dante; as they had their eyes sewn shut, they speculated on the nature of the person who could be there on that terrace, eyes open, living and breathing.

While these two are not named until further into the canto, we will introduce them here so as to identify them more easily as the two of them speak with Dante.

The first to speak is Guido del Duca, a Ghibelline from Ravenna in the Romagna region of Italy; some commentators say that he was of the Onesti family.

Guido del Duca is the image of the grudging type of Envy, which resents joy in other people. To the penitent Guido, looking back upon his life, the gay companionship which in the old days filled him with envy and uncharitableness now appears a thing full of happiness, to be wistfully regretted.1

The second speaker is also from Romagna, Rinieri de Paolucci da Calboli, who was from a Guelf family in Forli; he was a distinguished politician and podesta of Ravenna.

Guido addressed Dante, and asked him to identify his place of birth and name; he appealed to the virtue necessary to overcome the flaw of this terrace, that love that transforms envy. He also expressed astonishment and wonder—rather than envy—over the knowledge that Dante was a living man.

Dante rather cryptically made reference to his homeland by personifying the river Arno, an opening which will expand upon the themes the two will speak of.

Through central Tuscany there spreads

a little stream first born in Falterona;

one hundred miles can’t fill the course it needs.

I bring this body from that river’s banks;

to tell you who I am would be to speak

in vain-my name has not yet gained much fame.

xiv.16-21

This “little stream” in fact becomes the mighty Arno, whose source is in Falterona; it wound to the sea even further than Dante could measure; it travelled 150 miles before it released into the Adriatic Sea from the northeast coast of Italy. The banks from which Dante brought himself was the city of Florence.

Dante’s resistance to telling his name was perhaps reminiscent of the pride that he had purged on the first terrace; yet a bit still lingered, as he looked to his future fame and took note of it.

Guido had grasped Dante’s roundabout method of description and confirmed that it was indeed the Arno of which he spoke; his companion Rinieri did not understand the necessity of their discourse, as if the region were so terrible that it could not be named.

Guido, so envious in his lifetime, could now look upon the evils in Romagna, the region where he was from, and name them all; this opening personification of the river gave Guido the chance to speak out his invective. In this, his first speech of the canto, the river became the course along which each region could be named and defined and their villainies brought to light. From its source in the Apennine mountains along its mighty winding path to its final resting place in the sea, he defines the characteristics of the entire plain of the Arno.

Virtue is seen as a serpent, and all flee

from it as if it were an enemy,

either because the site is ill-starred or

their evil custom goads them so; therefore,

the nature of that squalid valley’s people

has changed, as if they were in Circe’s pasture.

xiv.37-42

Circe the enchantress, the daughter of Helios the sun god, exposed the lower natures of Odysseus’ crew in Homer’s Odyssey. Turning them into hogs, they lived as beasts on her island, until they were freed by Odysseus:

She came outside straightaway and opened the gleaming doors,

Then invited them in. All unaware, they followed her.

But Eurylokhos stayed outside, suspecting some kind of trick.

Once she’d brought them into the house, she sat them on couches and chairs;

She slowly stirred cheese and barley and tawny honey together

With Pramnian wine, while into their food she blended sinister

Drugs, to make them forget all about the land of their fathers.

After she gave it to them and they’d drunk it down, she suddenly

Tapped them with a wand and herded them into pigsties.

They took on the form of swine-their heads, their grunts, their bristles,

Their bodies-although their minds were as sound as they’d always been.

And while they went to and fro, weeping, Circe would toss them

Mast and acorns from oaks and the fruits of cornel trees

To eat-such stuff as wallowing swine are used to eating.

Odyssey x.230-2432

Such behavior was also found in those inhabitants of the Casentino valley along the Arno; as the river turned and wound it passed the Aventine, whose inhabitants resembled snarling dogs, those Ghibellines whose “force is feeble” (47). Here the river turned and ran past Florence, where the Guelf wolves reside. It continued to run past Pisan foxes, “full of deceit” (53).

Guido will not cease his tirade, even going so far as to speak of the grandson of his companion Rinieri—Fulcieri da Calboli—ushering in a prophecy of Fulcieri’s actions, one that would be useful to Dante when he returned to the world of the living:

Nor will I keep from speech because my comrade

hears me (and it will serve you, too, to keep

in mind what prophecy reveals to me.)

xiv.55-57

Fulcieri, of the Black Guelf party, in his revenge against the Ghibellines and White Guelfs, practiced extreme cruelty against them; in the words of Dante “he sells their flesh while they are still alive…he turns to slaughter” (61-62). So drastically had Florence been decimated, that like a stately forest that has been mown down, it cannot return to its former glory.

Rinieri paled and his face showed the grief that he felt upon these revelations; this dynamic between the two souls piqued Dante’s interest in their identities—for at this point he still did not know them by name—and he asked who they were that would speak to each other so.

Guido sardonically reminded Dante that he was asking them to do what Dante would not do for them—that is, name themselves; yet he obliged and relented as it was clear that Dante was in the favor of God’s grace, as implicated by his living journey through these realms of the afterlife. Guido gave his name and the fault which had landed him here:

My blood was so afire with envy that,

when I had seen a man becoming happy,

the lividness in me was plain to see.

From what I’ve sown, this is the straw I reap:

O humankind, why do you set your hearts

there where our sharing cannot have a part?

xiv.82-87

Guido epitomized the fault, that sin of envy, that reaction to others’ happiness and prosperity which brought the sinner only suffering.

The envious man grows lean when his neighbour waxes fat.

Horace, Epistles I.ii.57

Such action will bring about an equal reaction to the one so afflicted; by sowing envy, rather than reaping the bountiful wheat of the harvest, Guido had reaped only straw.

Be not deceived; God is not mocked: for whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap. Galatians 6:8

Envious humanity places its hopes and desires “where our sharing cannot have a part”; that is, on things of the earth that are material, that can be considered “mine” and “yours”, objects of envy which, even upon being obtained by the envious one, would not fulfill the deeper longing that they signify. Virgil will expound upon this idea in Purgatorio xv.45, that the ordered longings of the heart move more toward that which is common to all, sympathy and compassion and love, rather than to a grasping for possession of things that cannot be shared.3

Guido then introduced Rinier by name, and upon this introduction, began his lengthy lament over the region of Romagna; where earlier he had followed the course of the Arno river to expound upon the themes of ruin, here he lamented the lack of good and noble men and families in the speech that followed.

He began by describing the region of Romagna and its geographical boundaries, which extended from the river Po to the Apennines Mountains, from the river Reno to the Adriatic Sea; so distorted had the sense of goodness in this region become, that it was like a garden choked by poisonous weeds, impossible to cultivate.

He called out to the noble men of the past, famous and worthy men, embodying the question ubi sunt? Where were they now, when they were most needed? Within his speech, he named ten noble men, four distinguished family lines, and three towns known for their goodness. The noble men were dead and gone, the family lines had died out and become extinct, and the towns had lost any good families because of their corruption. Guido almost cannot bear the devastation.

To put it this way is to underscore the fact that the soul who speaks was a Romagnole, who has condemned his own in speaking to a Tuscan.4

One tercet proclaimed the longing of this lament most clearly, and was an inspiration to the later Italian poet Ludovico Ariosto as the theme for the opening of his epic poem Orlando Furioso.5

The ladies and the knights, labors and leisure

to which we once were urged by courtesy

and love, where hearts now host perversity.

xiv 109.111

Of loves and ladies, knights and arms, I sing,

Of courtesies, and many a daring feat;

Orlando Furioso, I.1-2

Here ended their conversation with Guido and Rinieri, and Dante and Virgil moved away. As upon their entrance to this second terrace, when the disembodied voices greeted them on the wind, again, spectral voices were heard; but this time rather than sweet sounds, they were accompanied as if by lightning and thunder. Here was the bridle of Envy, examples of the downfall of those who were overcome by their sin.

When we, who’d gone ahead, were left alone,

a voice that seemed like lightning as it splits

the air encountered us, a voice that said:

“Whoever captures me will slaughter me”;

and then it fled like thunder when it fades

after the cloud is suddenly ripped through.

xiv.130-135

This is Cain, who, in a fit of envy, slew his brother Abel, and as a punishment was cursed to wander the earth; his fear as he called out to God due to this punishment was that others would kill him for his sin. God marked him as a deterrent, so that others would not harm him.

And Cain said unto the Lord, My punishment is greater than I can bear. Behold, thou hast driven me out this day from the face of the earth; and from thy face shall I be hid; and I shall be a fugitive and a vagabond in the earth; and it shall come to pass, that every one that findeth me shall slay me.

Genesis 4:13-14

A second clap of thunder brought to their ears another voice sailing by them: this was Aglauros, she who was envious of her sister Herse, who was loved by the god Mercury, and was turned to stone when she tried to prevent him from visiting her.

In the classical world, Envy was herself a goddess, one who was called Nemesis in Greek and Invidia in Latin. In Ovid’s recounting of the story of Aglauros in his Metamorphoses, it is Invidia who infects her with Envy. Ovid’s telling is the most vivid rendering of the state of Envy that we can encounter in order to truly understand the nature of this affliction:

Once in the chambers of Aglauros, Envy

Obeys [Minerva’s] orders, touching the girl’s breast

With her rust-stained hand and filling it with thorns;

Now Envy breathes her poison in the girl,

And spreads her venom right into her bones,

And so that she would have a cause for grief,

Draws her a picture of her sister’s fortune…

Aglauros, maddened, feasts on her own heart

In secret wretchedness as anxious day

Succeeds each anxious night; groaning, she slowly

Wastes away, dissolving, just as ice does

In the uncertain light of early spring.

Her envy of her sister’s happiness

Consumed her, and she burned as does a fire

That smolders in a pile of thorny scrub.

Often she wished to die in order not

To see such happiness.

Ovid, Metamorphoses ii.1099-11176

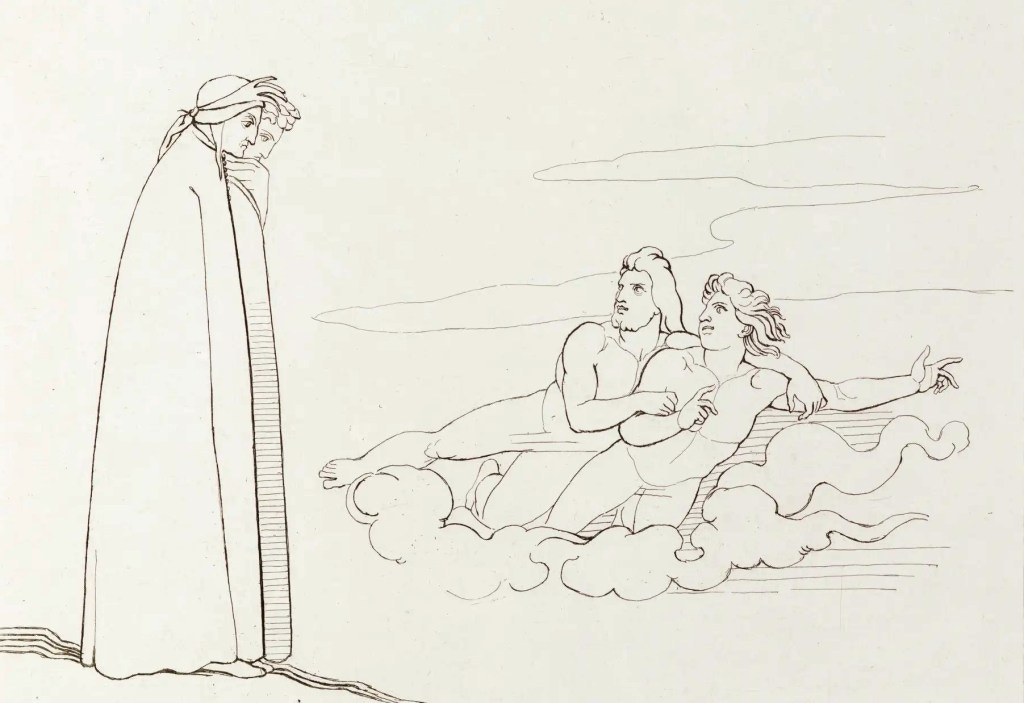

Upon hearing these voices, Dante drew closer to Virgil, who explained the nature of the bridle, or bit:

By now the air on every side was quiet;

and he told me: “That is the sturdy bit

that should hold every man within his limits.

But you would take the bait, so that the hook

of the old adversary draws you to him;

thus, neither spur nor curb can serve to save you.

xiv.142-147

Those who would take the bait are the unrepentant Envious, after which Satan could reel them in like a fish caught on a hook; neither the whip (the example toward goodness) nor the bridle (the example of sin that will keep one from further sin) would be of any avail.

Heaven would call-and it encircles-you;

it lets you see its never ending beauties;

and yet your eyes would only see the ground;

xiv.148-150

Virgil called for the ideal of lifting up the eyes, lest one be overtaken by that bait.

💭 Philosophical Exercises

You must find your dream, then the way becomes easy.

~ Herman Hesse

One of my favourite writers, Vladimir Nabokov, whose name I cannot stop mentioning in my newsletters and podcasts, analyzed and valued writers by their ability to tell tales in fresh, new ways. There are, of course, frameworks that some writers use to tell stories—they become repetitive, and we get used to them. Meanwhile, some writers are so distinct and unique that they tell tales in a way nobody has done before them, and Dante, in his masterpiece The Divine Comedy, gives us a masterclass scene in storytelling in each canto.

I.

When we enter this canto, Dante turns us blind intentionally. He makes us feel and understand what it's like to be blind because when we enter this canto, we hear voices, but we cannot distinguish who these voices belong to. Is it still Sapia speaking from the previous canto, or is it someone new?

The beauty of this canto also lies in this small detail: when Dante finally sees Guido and Rinieri after his eyes open; because at the start, we feel as if Dante's eyes, our protagonist's eyes, as well as ours, are sewn shut like the eyes of the envious.

But then we start to see. We see those two figures, Guido and Rinieri.

This pair, particularly Guido, who will be at the forefront of the scandal, do not know that Dante's eyes are not sewn like theirs. In fact, they know almost nothing about Dante, because all he tells about himself, when asked, is that he is from Tuscany. They do not even know his name. Who knows? Maybe if their eyes were not sewn—if Guido and Rinieri's eyes were not sewn—they would be envious of Dante for his ability to see.

I found this little detail, hidden in plain sight, to be unique, because Guido believes that maybe Dante doesn't see as he sees, and of course sight is an important part here. So maybe him not knowing stops him from being jealous.

II.

But as we know, Dante is not just a great storyteller who reinvents ways of telling stories over and over in each canto, he is also a master psychologist. He's a priest of our souls, because Guido and Rinieri represent two types of envy, or better to say, two ways envy unfolds in the world.

Guido is outspoken. He is loud, he is direct. In this canto we do not hear Virgil until the end, but Guido is fully present. He is the key character here. Envy can be outspoken like Guido—loud, direct, like the banging of drums.

Rinieri, however, is quiet, yet present. He speaks only six lines, as Robert Hollander observes, but he seems hidden. In fact, Rinieri never addresses Dante directly. He always asks Guido, and Guido passes Rinieri's words on to Dante. This is how envy operates in the world in two ways: one is outspoken, like Guido, loud as drums; the other is working behind the scenes, hidden, as I said, but present. One disturbs a wide number of people directly, becoming a leader of envy, and the other, hidden behind the scenes, whispers envious words into the ears of weak people.

At first, what they both say makes sense—sounds virtuous and fair. And of course, to a degree, their words throughout this canto are. But try reading their words while holding a mirror toward them, and we see that envy always disguises itself as virtue: the prideful scorn that Guido has for his people, the heightened judgment. Yes, these souls are in a better place—they are in purgatory—but they haven't cleansed or purified themselves yet. When we look at the words spoken by Guido in particular and put them in reverse, put them in front of a mirror, we can see that the envy that drove him in his previous life still guides his thought processes here. He still has a long journey to purify himself.

Guido's lament, where he lists names of families, is another masterclass from Dante on how to hide meaning in plain sight. Guido begins with individual names—Bente Traversari—and then he continues and expands to families—Conti, Guidi—and ends with entire regions: Tuscany and others. It is as if, where in the Bible names are named in order of who begat whom, here we see who corrupts whom. It is the reverse of the book of life: individuals corrupt families, then families corrupt regions. Envy is a contagion, a disease, and as we discuss them, there is still envy present in Guido's words. He is envious of the past, of better times. He's envious of times when there was less corruption.

III.

Now that the air was quiet all around us,

he said to me: ‘That was the bit and bridle

to keep a man within his bounds.

-

But you mortals take the bait, so that the hook

of your old adversary draws you to him,

and then of little use is curb or lure.

(line 142 - 147)

The ending of this canto seems like a musical symphony where the orchestra slowly fades the sound until it becomes barely audible. There are many references to Boethius's philosophy, which we'll explore in the next section.

But let me briefly conclude what Dante tried to convey to us here. First, I believe one of the most important lessons for me is that envy works in two ways, and both of them are scary. The first is direct, as with Guido, while the second works behind the scenes. And of course, it is the second one—Rinieri's way of envy—that scares me the most.

But there is a second thing that is even more terrifying: envy often hides itself as virtue. There are subtleties of sin in Purgatory, because in the Inferno, sin was very direct, brutal, cruel. In Purgatory, it is equally terrifying, and if you are not alert, if you let down your awareness, you might not notice this element—this way that sin can present itself as virtue. Because envy often presents itself as the desire to take someone's property, as political envy. It often hides itself as a virtuous thing—taking something that doesn't belong to you. This envy presenting itself as virtue is incredibly terrifying, because often envious people try to present their envy as a good thing. It is a perversion and denaturalization of morality.

I think, finally, the biggest lesson for those who are observant here in this canto is this reverse book of life: that envy is not something that can be contained within an individual. Envy spreads like fire—in general, how every vice, every disordered state does. I think Dante's genius here is both as a storyteller and as a psychologist.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. Cain

Then the Lord said to Cain, “Why are you angry? Why is your face downcast? 7 If you do what is right, will you not be accepted? But if you do not do what is right, sin is crouching at your door; it desires to have you, but you must rule over it.”

8 Now Cain said to his brother Abel, “Let’s go out to the field.” While they were in the field, Cain attacked his brother Abel and killed him.

9 Then the Lord said to Cain, “Where is your brother Abel?”

“I don’t know,” he replied. “Am I my brother’s keeper?”

We first met Cain in Inferno, condemned for the crime of fratricide. Yet at the heart of his sin was envy not just the act of murder, but the desire that his brother should have less. He looked upon Abel and could not bear his joy, his favour, his fruitfulness.

The spirit of Cain lingers in this canto, a quiet shadow in the song.

II. Boethius (Foxes and Earthly things)

“You will say that the man who is driven by avarice to seize what belongs to others is like a wolf; the restless, angry man who spends his life in quarrels you will compare to a dog. The treacherous conspirator who steals by fraud may be likened to a fox;…the man who is sunk in foul lust is trapped in the pleasures of a filthy sow”

~ Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy

Dante’s comparison of sinners to animals is inspired by Boethius, particularly a passage from The Consolation of Philosophy. (A podcast series on Boethius is coming soon!) The verse accompanying this part of Boethius’s masterpiece includes a reference to Circe, the enchantress who, in ancient myth transformed men into beasts.

(I might record a separate episode on Dante and Boethius at some point as well)

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

The heavens call to you and wheel about you,

revealing their eternal splendours,

but your eyes are fixed upon the earth.

For that, He, seeing all, does smite you.’

~ (lines 147-151, Hollanders’ translation)

Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory 178

Daniel Mendelsohn translation

Dante will ask Virgil, “What did the spirit of Romagna mean / when he said, ‘sharing cannot have a part’” (xv.44-45) guiding Virgil to give an exposition upon this idea.

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on Purgatorio 309

Which was also illustrated by Gustave Dore

Charles Martin Translation

Thank you for pulling all of this together, Dante, the Odyssey, Boethius.

It's very minor in comparison, but I noticed a few small errors:

reaction to others['] happiness and prosperity

Envious humanity places it’s [its] hopes

and it’s [its] geographical boundaries

I am not good at keeping track of time. These blog posts have become markers of time for me this year. I am reading Mandelbaum's and Musa's translations between the posts. Thank you for all of this Vashik. You help me see something redeeming in some of these canton that seem so graphically unpleasant. I have to admit I am curious for what is ahead!