This article is the third part out of a three-part series introducing my read-along, which begins in January 2025:

The 1st part of this article 👇

The 2nd part 👇

What is your aim in philosophy?

To show the fly the way out of the fly-bottle.

~ Ludwig Wittgenstein

‘The product of the philosopher is his life (first, before his works). That is his work of art.’ - wrote the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who could say in a single sentence what others attempt to say in an entire book.

His fellow philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein would agree with him, as Wittgenstein himself noted that ‘philosophy is not a theory but an activity.’ Wittgenstein did not throw empty words to the wind, as the Russian saying goes. He served in the Austro-Hungarian army during the First World War and volunteered to be placed on the front lines. This decision takes on a different significance considering that he came from one of the wealthiest families in Europe and had the means to avoid military service entirely.

Why did Ludwig Wittgenstein, who once hired an entire ship solely for himself, volunteer to face almost certain death on the front lines? Inspired by Tolstoy’s The Gospel in Brief, Wittgenstein thought that death could have a reinvigorating effect on one’s mind. Most people encounter the danger of death only once in their lives, often realising the value of life too late. Wittgenstein believed that by experiencing enemy bullets whizzing past his head, he could embrace a sense of urgency and attentiveness, fully grasping each moment of his existence.

Both - Nietzsche and Wittgenstein - considered philosophy, not an abstract theory but a way of living and a means of self-transformation. What they were doing, however, was nothing new. They were following the footsteps of thinkers that came before them, thinkers who also saw that philosophy could show the fly the way out of the fly bottle, thinkers such as Shaftesbury, Spinoza, Boethius and ultimately the ancient philosophers such as Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, Epictetus and Socrates himself.

Pierre Hadot: Philosophy as a Way of Life

It was the French philosopher Pierre Hadot who noticed the invisible thread that connected all these philosophers together across centuries and even millennia.

In 1944, Hadot was ordained, but he left the priesthood six years later to pursue the academic study of philosophy. Influenced by the Greco-Roman philosophers such as Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus, Hadot coined the term ‘spiritual exercises’ which means ‘practices ... intended to effect a modification and a transformation in the subjects who practice them.’

One could speculate and say that the term ‘spiritual exercises’ that Hadot coined possesses echoes of his religious past. Whether true or not, over the past couple of years I felt indescribably inspired by Hadot’s works. His books changed my perspective of what philosophy is, and what its true purpose is, transforming the way I read entirely. Hadot unveiled to me that the masterpieces of Dante, Goethe, Hugo, and others contain ‘spiritual exercises’, and taught me how to recognise and extract them.

Reading as a Spiritual Exercise

Hadot’s redefinition of philosophy, not as a set of doctrines and theories, but as a practice of self-transformation and a way of life, entails the urgent task of redrawing the boundaries between philosophy and other disciplines.1

Poetry, paintings, essays, and novels contain within them spiritual exercises that can lead to self-transformation and a philosophical way of life. It is because of the narrow-mindedness of contemporary academic philosophers that this wisdom was neglected. For Hadot, the works by the German genius Goethe for example, contain as much wisdom as the works of philosophers like Descartes or Kierkegaard if we pay the right attention to them.

Every reader knows this to be true. Dante’s great poem transformed my life more than any philosophical work I have ever read. This is why I want to apply Hadot’s approach to my read-along that begins in January 2025.

It is time to bring back the wisdom of the ancients to our lives but how exactly can we read Dante or Goethe for self-transformation? What would be the practical approach of this type of reading?

John Sellars2, who spent his career studying Hadot, highlights three key parts of philosophy as a way of life:

We need to recognise that the ultimate motivation of philosophy is to transform one’s way of life; (i.e. philosophy is not a theory, but an activity)

that there ought to be some connection and consistency between someone’s stated philosophical ideas and their behaviour.

that actions are ultimately more philosophically significant than words.

Thus, if we want to read great books, as Hadot entrusted us, we have to a) read each masterpiece with the aim of drawing lessons from it b) we also need those lessons to become spiritual exercises), and finally c), we need to convert those exercises into actions.

For centuries, curious people have been practicing this kind of reading. They were reading Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations alone in their rooms in their free time, making notes on the margins, attempting to get close to the philosopher-king by imitating his spiritual exercises. Today, we are at a privileged moment in history, where we can connect with like-minded individuals and collectively read and discuss literary masterpieces. This is important because as Tarkovsky said: A book read by a thousand different people is a thousand different books. Each of us can uncover a spiritual exercise within Dante’s The Divine Comedy, for instance, and share insights that other readers might have overlooked.

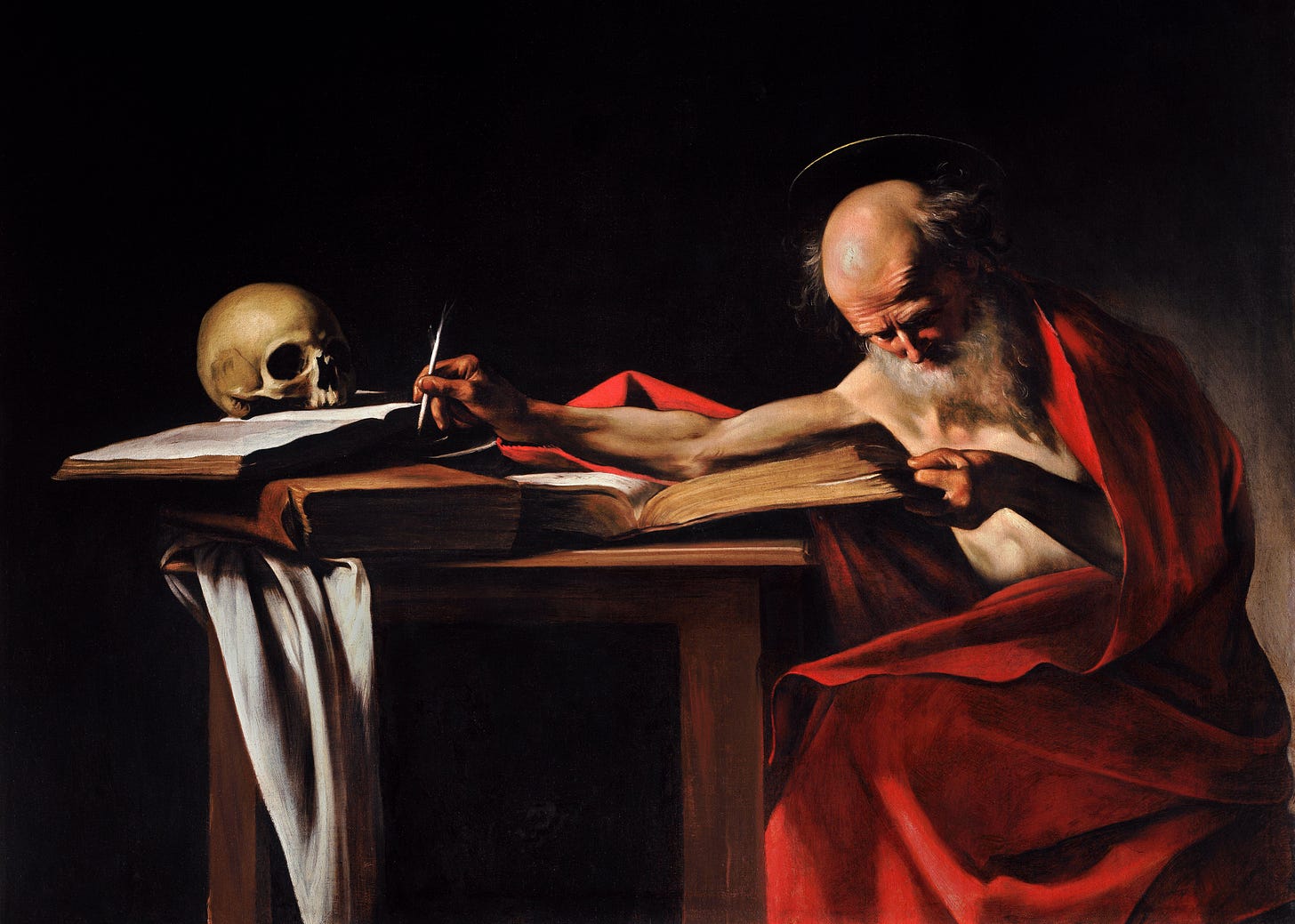

Let us repay our debt to the great authors with the currency of our undivided attention since ‘absolutely undivided attention is prayer’ as my favourite Simone Weil once said. Let the great masterpieces of literature show us - the flies - the way out of the fly-bottle. In the same way, as Wittgenstein volunteered himself to be on the frontline to experience each day of his life as if it were his last, let us read each masterpiece of literature as if it is the last time we are going to experience it.

As always Confide tibimet.

Proofread and edited by Lisa Statler.

Don’t Forget to Live by Pierre Hadot (quoted from Preface)

I would recommend reading the article by John Sellars in full: https://parrhesiajournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/parrhesia28_sellars.pdf