Schadefreude: Why We Rejoice in the Ruin of Others?

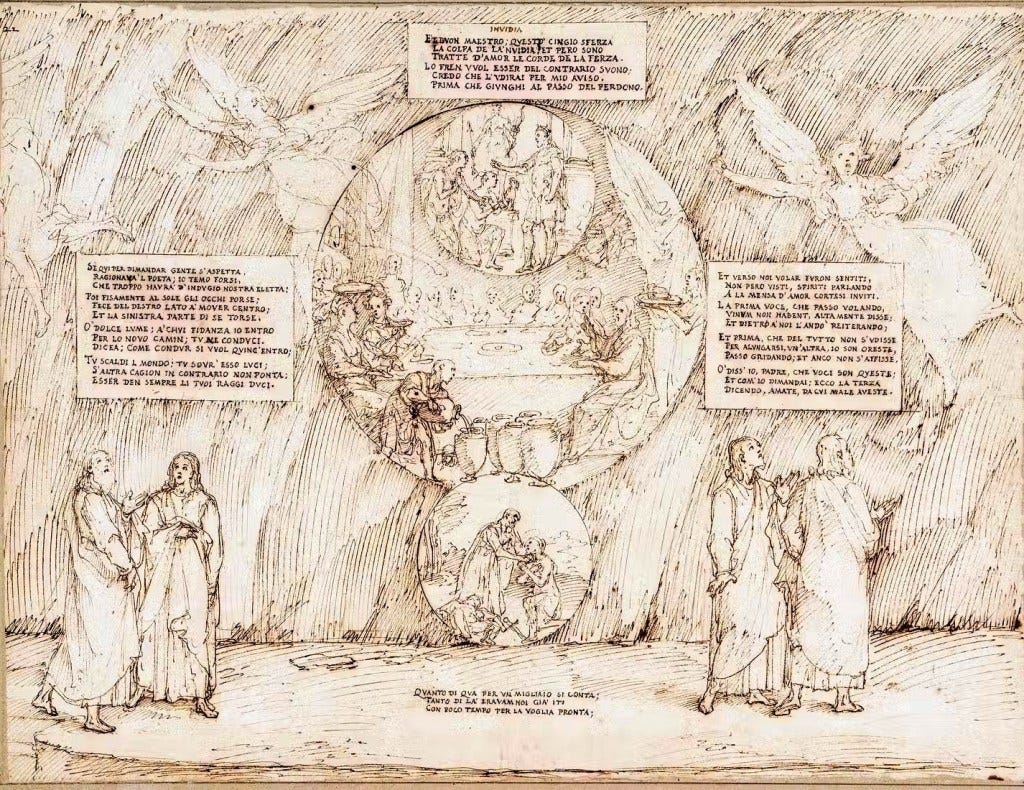

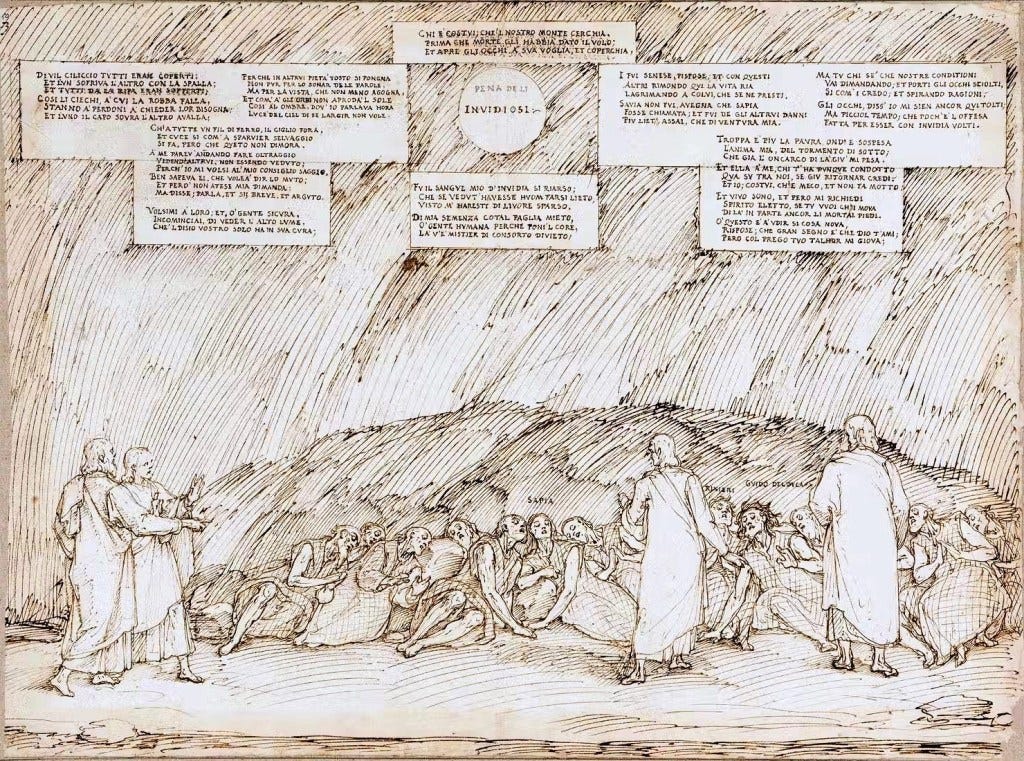

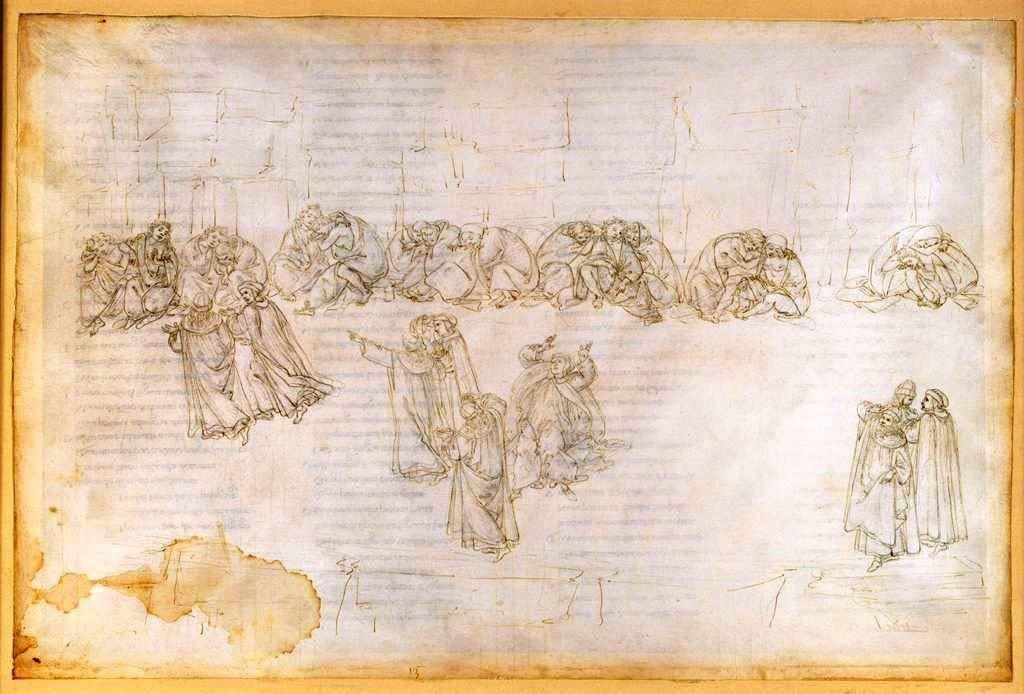

(Purgatorio, Canto XIII): Sapia, Envy, Palliades and rescuing friends

‘Schadenfreude’ (German) - to take pleasure from someone’s misfortune

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

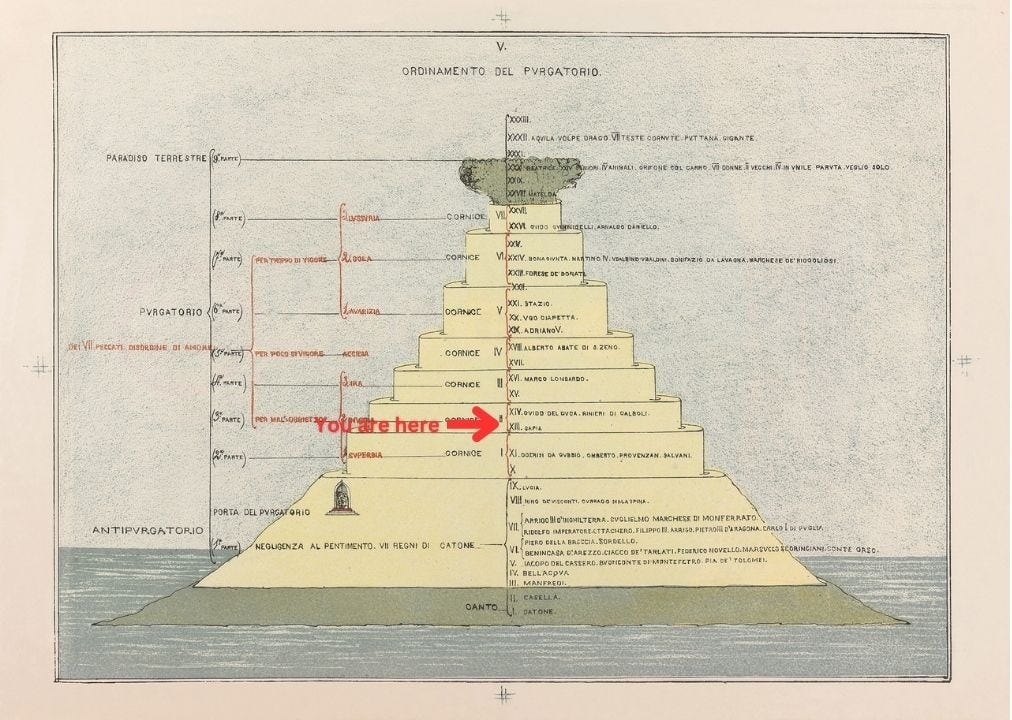

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Thirteenth Canto of the Purgatorio, Dante and Virgil meet the Envious. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

The second terrace of Purgatory – They follow the direction of the sun – Disembodied voices give examples of charity – Mary, Orestes, the Sermon on the Mount – The scourge and the bridle – The Envious – Their eyes sewn shut – Sapia the Tuscan

Canto XIII Summary:

Dante and Virgil had reached the ledge of the second terrace, which ran round the entirety of Purgatory in ever smaller circles as the mountain rose higher and higher. That ledge was cut into the rock of the mountain, the journey being that which “delivers man from sin” (6).

Unlike their entrance into the first terrace where they were met by the white marble carvings, upon this terrace they saw neither carvings nor souls; in fact, the tone of this terrace was set by the color of the rock; rather than white marble, this terrace was a livid color, the color of envy, a dark blue grey shade.

Virgil stated their need for action, but their direction was still uncertain. He concluded that the counterclockwise direction was the correct one based on the sun, and turned to lead them in that direction:

“O gentle light, through trust in which I enter

on this new path, may you conduct us here,”

he said “for men need guidance in this place..

You warm the world and you illumine it;

unless a higher Power urge us elsewhere,

your rays must always be the guides that lead.”

xiii.16-21

As their light steps let them move quickly along, their first hint at the nature of the second terrace made itself known through the appearance of disembodied voices, rushing through the air towards them, with a “courteous invitation to love’s table” (28).

Three examples of this embodiment of the ideal of charity, or love followed; the first voice, calling loud and clear, called out Vinum non habent; they have no wine. This, spoken by the voice of Mary at the wedding feast at Cana, asked for intercession on behalf of the guests, and resulted in Jesus’ performing his first recorded miracle, that of turning water into wine. Mary is represented first on this second terrace, just as she was on the terrace of Pride.

And the third day there was a marriage in Cana of Galilee; and the mother of Jesus was there: And both Jesus was called, and his disciples, to the marriage. And when they wanted wine, the mother of Jesus saith unto him, They have no wine…Jesus saith unto them, fill the waterpots with water. And they filled them up to the brim. And he saith unto them, draw out now, and bear unto the governor of the feast. And they bare it. When the ruler of the feast had tasted the water that was made wine, and knew not whence it was, the governor of the feast called the bridegroom.

John 2:1-3,7-9

The second spectral voice that came to them is classical, and called out to them “I am Orestes!”

Orestes was the son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra; Agamemnon was the brother of Menelaus, whose quest to rescue Helen from the Trojan prince Paris was the event that began the Trojan war. As Agamemnon prepared to set sail for Troy, his fleet was stalled by lack of wind. In order to appease the goddess, he sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia and then set sail. On his return, his wife, Clytemnestra and her lover, Aegisthus killed Agamemnon for his cruelty in sacrificing his daughter, and in revenge, their son Orestes—brother to Iphigenia—plotted and carried out the murder of Clytemnestra and Aegisthus; Orestes friend, Pylades, attempted to protect his friend by taking his place as he was being sought out for his crime, and hence, called out, showing a divine and sacrificial love, “I am Orestes!” Orestes would not allow it, but Pylades willingness was such that his actions became a second example of pure charity. Orestes story is told in full in the Euripides play the Orestia.

Just as Dante cried out to Virgil to inquire about the nature of the voices, a third voice came to them through the air, “Love those by whom you have been hurt” (36); this was from the Sermon on the Mount, the teachings of Jesus to the multitudes:

But I say unto you, love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you. Matthew 5:44

Finally the poet and pilgrim could identify the sin of this terrace through its opposite expression as given in the three voices:

And my good master said: “The sin of envy

is scourged within this circle; thus, the cords

that form the scourging lash are plied by love.

The sounds of punished envy, envy curbed,

are different; if I judge right, you’ll hear

those sounds before we reach the pass of pardon.

xiii.37-42

The envious man is afraid of losing something by the admission of superiority in others, and therefore looks with grudging hatred upon other men’s gifts and good fortune, taking every opportunity to run them down or deprive them of their happiness. On the Second Cornice, therefore, the eyes which could not endure to look upon joy are sealed form the glad light of the sun, and from the sight of other men. Clad in the garments of poverty and reduced to the status of blind beggars who live on alms, the Envious sit amid the barren and stony wilderness imploring the charity of the saints, their fellow-men. Because they are blind, the Whip and Bridle of Envy are brought to them by the voices of passing spirits.1

The scourge, which goads the sinners toward the virtue that opposes envy, is made up of three thongs, three examples of love, of charity. The curb, which deters the sinners from envy and is opposed in its function to the scourge, is comprised of examples of envy and must be of a “contrary sound.” Following the pattern established on the first terrace, these examples will be heard later, as Virgil surmises.2

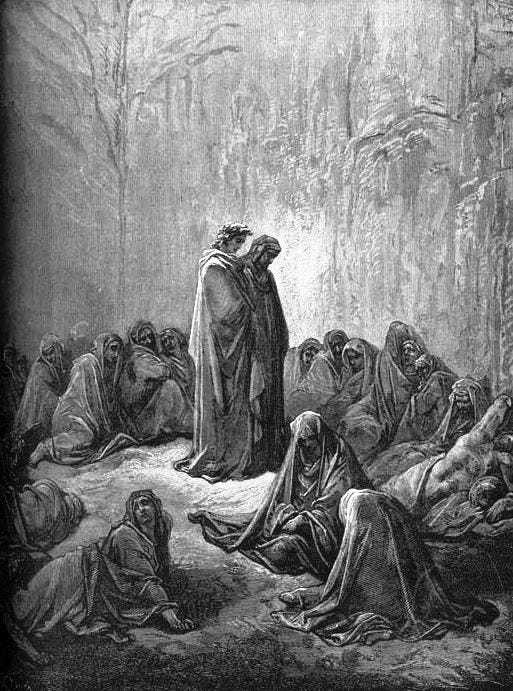

Virgil pointed out a group which Dante strained to see, so perfectly had they blended in with their surroundings.

I opened-wider than before-my eyes;

I looked ahead of me, and I saw shades

with cloaks that shared their color with the rocks.

And once we’d moved a little farther on,

I heard the cry of, “Mary, pray for us,”

and then heard, “Michael,” “Peter,” and “All saints.”

xiii.46-51

These figures, whose cloaks were the same livid color of the stone, sat leaned against the wall of rock, and called out with what amounted to the prayer of the Envious, the Litany of the Saints; so pitiful was their countenance and the contrapasso of their punishment and their prayer that Dante’s heart was moved with intense compassion, perhaps as “his token participation” of the intensity of this punishment.

These souls, backs against the rock wall, their heads leaning on the shoulder next to them, were dressed in robes symbolic of penitence, coarse like haircloth; just as the blind beggars who sat in front of churches on special days of Indulgence. Their blindness, however, did not come from a natural condition:

And just as, to the blind, no sun appears,

so to the shades-of whom I now speak-here,

the light of heaven would not give itself;

for iron wire pierces and sews up

the lids of all those shades, as untamed hawks

are handled, lest, too restless, they fly off.

xiii.67-72

As terrible as the image seemed, with those eyelids sewn shut, the nature of such actions had a deeper meaning than mere blindness, it is a matter of temperance of qualities.

To tame a hawk that has been caught wild it is necessary to blindfold her. In the west this is usually done with the hood, but the method of sealing the eyes was also known in Dante’s time, being perhaps imported from the east, where it is still used. It is effected “with a sharp needle and waxed silk. Carefully, the falconer threads the silk through the edge of the lower eyelids, drawing them closed by twisting the thread and tying it across the bird’s head. This method does not hurt the falcon, and as she sheds her fear the thread is gradually untwisted, letting her see a little more light, until finally the eyes are wide open and the thread can be removed. 3

Think of that sun that was guiding Virgil and Dante next to the imagery of the falcon receiving bits of light at a time until it was strong enough to receive the full light of the sun. Those disembodied voices were there for the benefit of the blind.

Dante gazed at these poor souls and looked at the tears that squeezed through their shut eyelids; he asked if any were from his home country, for Dante could be helpful to them if there were. A woman from among the crowd answered him, and expressed the unity of their purgatorial city, that they were a “citizen of one true city” (95).

This was Sapia, who explained the envious nature of her heart, and what brought her to this realm of purgatory.

The soul who speaks is indulging in a customary play on the etymology (apparent etymology at least) of names that is expressed in the dictum “nomina sunt consequential rerum” (names are the consequences of things) mentioned by Dante in Vita Nuova.4

In explaining her fall, she described her joy in seeing her own people defeated; she had even prayed for their downfall. So shameless was she that she had cried out to God, in her moment of joy at their defeat “Now I fear you no more!” (122); her nephew is the Salvani whom we encountered in canto xi, he who tried to become the dictator of Siena, but redeemed himself through begging for the ransom for his friend, patiently working through that penance of Pride with the great stone upon his back. She referred to herself as the blackbird in her cry against God:

In Lombardy the occasional fine, spring-like days which sometimes occur in January are popularly called giorni di merla, “blackbird’s days,” the fable being that the foolish bird, seeing the sun, cried out: “lord, I fear Thee no more, spring has come!”5

This was her state until her final moments of repentance; she would have arrived into Ante Purgatory if not for the prayers and intercession of one Pier Pettinaio, a famed and honorable comb seller and pious hermit, who prayed for her soul.

Sapia asked Dante for his story, he with unsewn eyes and living breath; he proved how aware he was of his own failings:

“My eyes” I said, “will be denied me here,

but only briefly; the offense of envy

was not committed often by their gaze.

I fear much more the punishment below;

my soul is anxious, in suspense; already

I feel the heavy weights of the first terrace.”

xiii.133-138

She wondered at how Dante had arrived there, being alive. He mentioned the quiet Virgil by his side; he also offered prayers on her behalf once he was back in the land of the living, fulfilling the prayer that he made when he asked the gathered souls if there were an Italian that he could speak to among the Envious. She asked if he could also restore her name, should he ever be in her home on Tuscan soil.

Of those Tuscans she had much to say; those who “dream of Talamone” referred to the failed project of the restoration of a port into a grand harbor at the loss of thousands of florins. The other to a project attempting to tap underground fresh water from a source called the Diana (after the fountain whose water it already supplied).

Those admirals could refer to a variety of players in both of these schemes, who would lose out, either in money, hope, or their very lives.

💭 Philosophical Exercises

The sure mark of one born with noble qualities is being born without envy.

~ La Rochefoucauld

Prelude

I wanted to highlight this part that I found inspiring before proceeding to the main part. Virgil’s words stunned and gave a breath of fresh air when he said:

‘If we linger here to ask directions’

The poet reasoned, ‘before we choose our way,

I fear we may be long delayed.’

~ (Hollander’s translation, lines 10-12)

I interpret this as the great poet telling us that we should choose our own path, make our own decisions, take responsibility for our own choices. If you wait for someone to come to your rescue, you might wait for far too long.

I.

In Russian, there are two distinct terms for envy that describe this complex vice. The first type is called белая зависть (white envy) and the second is черная зависть (black envy).

White envy emerges when you observe someone who has achieved great success or happiness, something you crave and desire. This form of envy carries within it the impulse to emulate their path, to follow in their footsteps and undertake the same toils they endured to reach their success. It implies a desire in you to do the hard toil so you could reach the same heights.

As the poet Sallust once declared:

"They envy the distinction I have won; let them therefore envy my toils, my honesty, and the methods by which I gained it."

This Sallustian nature of envy—that of the Russian “white envy”—contains within it both the desire and the willingness to imitate the hard work required for achievement.

This stands in stark contrast to what we might call the Dantean view of envy—the medieval Christian understanding of this vice. Their perception of envy is rightfully dark and bleak.

This darker form seeks not to rise to another's level, but to bring them down. It rejoices in others' failures and desires their downfall even when we have no direct stake in the outcome. To use a modern day example: if someone applies for a job you desire, black envy wishes for their rejection not because you want that particular position, but because their failure brings you perverse joy.

I want to remind my reader of a scene I discussed in one of the previous posts of Purgatorio; this scene comes from Victor Hugo's Les Misérables. Jean Valjean is forced into crime, gets arrested, spends years in prison, and then emerges from there only to face rejection from all society.

When he finally finds shelter with Bishop Bienvenu, despite warnings against harbouring an ex-convict, the clergyman lets the man in. He offers him food, shelter, and even his own bed.

Initially, Jean Valjean remains mistrustful, his eye focused entirely on the external world, envying those who live regular lives. But through the bishop's extraordinary charity, his inner eye begins to see, and he awakens from his destructive ways.

This transformation becomes particularly poignant when we consider Dante's punishment for the envious in Purgatorio. Few punishments in the Inferno have caused in me such a terrifying reaction as Dante's description of sinners with their eyes sewn shut by iron wire. This imagery is both terrifying and profound, the wire echoes Christ's crown of thorns, creating a form of visual crucifixion. These souls must now learn to see with their inner eyes.

Throughout this canto, the envious must reorient themselves through voices alone. Their physical eyes have been corrupted and poisoned. Dante uses the word invidia, which derives from invidere—meaning both "not seeing" and "seeing against." As the Persian poet Rumi described, the envious eye becomes like a vulture's beak, consuming rather than nourishing.

It is significant that this terrace follows immediately after the terrace of pride. While pride, for all its vanity, possesses a certain vitality and brightness, envy appears utterly grey, livid, lifeless, devoid of soul, creativity, or brightness.

The Russian understanding aligns remarkably with Aristotle's definition:

"Jealousy is both reasonable and belongs to reasonable men, while envy is base and belongs to the base. For one makes himself get good things by jealousy, while the other does not allow his neighbor to have them through envy."

There's a joke I heard from a contemporary philosopher that perfectly illustrates this destructive nature: God appears to a man and offers to grant any wish, with the condition that his neighbour will receive twice as much. The envious man responds: "Then pluck out one of my eyes."

Satan himself exemplifies this vice, rebelling against God purely from envy of His position. In our contemporary world, envy plays a particularly insidious role because we all experience it to some degree, yet we deceive ourselves into believing it afflicts everyone but us. As Dante said himself:

"Pride, envy, and avarice—these are the sparks that have set on fire the hearts of all men."

How does Dante propose we fight and overcome this sin?

His method in Purgatorio follows a consistent pattern: first presenting positive examples for imitation (the images on the rocks in the terrace of pride, for example), then showing the consequences when proper order is violated (the theme we explored in the previous canto).

For Dante, influenced by Thomas Aquinas’s and St. Augustine’s thought, sin is not merely an act but a disorder, a lack of proper arrangement in the soul. The envious, whose vision was disordered and who failed to see the world as it naturally should be, have their eyes sewn shut so they might train their inner sight.

Dante offers three remedies, or philosophical exercises, through his examples:

First, through Mary at the wedding in Cana: When she notices "they have no wine," her concern centres entirely on others well-being, not her own needs. Mary represents the antithesis of envy, her joy lies in others joy. She demonstrates empathetic attention, interceding for others needs and speaking not for herself but for the wedding hosts.

Second, through the classical tale of Orestes and Pylades: When Orestes faces execution, his friend Pylades claims to be Orestes to save him, while Orestes insists "I am he." This true friendship involves self-sacrifice, with each willing to die for the other, a competitive generosity that mirrors perfect love and stands opposite to envy's destructive nature.

Third, through Christ's words on the cross: "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do." This example strikes me as particularly profound because it demonstrates the ability to recognize the limits of our understanding of others. It represents love in its purest form—love without ego, love beyond comparison, accepting people as they are.

These three remedies form Dante's prescription: care for others, self-sacrifice (not merely physical, but having something genuinely at stake), and the dropping of ego. This cures what Dante calls invidere (seeing against) the desire to destroy what we cannot possess.

The parallel with Les Misérables completes this understanding. Jean Valjean's eyes were opened and his envy dissolved through the incredible charity and kindness that Bishop Bienvenu offered. Even after Jean Valjean steals from his benefactor, when police return him to Bishop with the stolen goods, Monsieur Bienvenu not only forgives but gives even more, declaring these were gifts, not an act of theft.

The beauty of charity and kindness wins every time, transforming the envious eye that sees against into the loving eye that sees with compassion. In recognising both forms of envy (the Russian / Aristotelian): the white that might inspire emulation and the black that seeks only destruction—we can choose the path that leads not to the sewn eyes of Purgatorio, but to the opened eyes of redemption.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. Virgil’s Prayer

‘“O gentle light, through trust in which I enter

on this new path, may you conduct us here,”

he said, “for men need guidance in this place.You warm the world and you illumine it;

unless a higher Power urge us elsewhere,

your rays must always be the guides that lead.”~ lines 16 -18

As Hollander notes, Virgil’s prayers are left unanswered. I believe the reason for this is that the nature of pagan prayer differs fundamentally from the essence of the Christian one. We have explored Kierkegaardian prayer in the canto of simony in the Inferno. A prayer does not aim to change the world but to change the one who prays. Virgil prays for the Sun to act, while the whole nature of Purgatorio is to change oneself through prayer.

II. Pity and Compassion

I think no man now walks upon the earth

who is so hard that he would not have been

pierced by compassion for what I saw next;for when I had drawn close enough to see

clearly the way they paid their penalty,

the force of grief pressed tears out of my eyes.- lines 52-57

In the Inferno, Dante’s goal was not to pity the damned, since they deserved and brought themselves to the state of infernal madness and punishment. In Purgatorio, it’s different. Here, Dante has to feel compassion, has to put himself in the shoes of the souls. Dante even reflects that, after his death, he expects to spend time on the terrace of Pride. But here, in this canto, he acknowledges that Envy will not detain him for long.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

I try not to repeat quotes across different sections of these letters, but Dante’s message, that we must choose our own path, compelled me to copy these lines into my notebook.

‘If we linger here to ask directions’

The poet reasoned, ‘before we choose our way,

I fear we may be long delayed.’

~ (Hollander’s translation, lines 10-12)

Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory 170

Charles S. Singleton Commentary on Purgatorio 274

Sayers 171

Singleton 280

Sayers 172

A lot of food for thought in this Canto.

More on Bl. Pietro Pettinaio if anyone is interested. What a life.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pietro_Pettinaio

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02666286.2016.1144437