This article is also a podcast episode👇 Listen 🎧

On my third day of moving to London, I had a horrible experience. I was on the train to work and a group of football fans told me explicitly that I was not welcome in this city as an immigrant.

My excitement of being and living in London almost died down until the very evening of that same day. On my way back home, I was approached by a young man who almost angrily started asking me: Are you from London? Are you from London?

Every mental and physical muscle of mine was prepared to fight at that moment. But, then the young chap told me that something happened to his family and he was urgently looking for the train station and was wondering if I knew where he could find it.

This happened eight years ago and I had no such bad experience in London ever since, but I’ve learned a lesson from this situation that will stay with me for a long time.

Sometimes we surrender our reason to our reflexes. We cease to pay attention and refuse to think anew. This, in its turn, leads to our past experiences to define our future ones.

I. Journaling with Weil

At that time I had no idea who the philosopher Simone Weil was. I hadn’t even heard her name, but the diary entries she wrote in the early 1940s echo closely with the journal entries I wrote in 2015.

In her journals, she wrote that ‘what we call the world are the meanings that we read.’

In another entry she brings an example: ‘While walking along a deserted road at night, I glimpsed a man off to the side, waiting to ambush me. This menacing presence turned to be false when I came nearer and realised that it was, in fact, a tree.’

What has changed, of course, is not the world, but Weil’s reading of it. In the same way, as my reading of the world changed when I understood that the intentions of the young chap weren’t aggressive, but were actually benign.

In contrast to thinkers such as Locke or Sartre, who say that our outlook on the world is defined by our sensations, Weil states that our outlook is defined by our values. In other words, the way you read the world and interpret it depends on your values.

Locke and Sartre would say that our behaviour is just a consequence of external events. For example, that one steals because they were born poor. Weil, however, gives us a choice. She says that your inner world, your values, define who you’re going to become. You don’t have to become a robber just because you were not born rich.

But, of course, my dear reader, there is a big question that hovers above us: Is there a centre, from where we can see all the different ways the world could be ‘read’? How can we see all the other different readings of the world?

II. Attention, Attention. Here and Now.

In her notebooks, Weil writes that we can find this centre by ‘paying attention’. Weil’s definition of what ‘attention’ means, however, is different from everyone else’s.

For Weil, ‘attention’ is not just the muscular effort of concentrating or focussing on certain tasks as some thinkers choose to define it1. ‘This kind of [muscular] attention flourishes in therapists’ offices, business schools, and funeral homes. It is a performative rather than reflective act, one that displays rather than truly pays attention.’2

Instead, ‘to pay attention’ for Weil is more about the withdrawal of the self. To explain this, let’s take a look at Weil’s teaching style. (I bet you would like to have a teacher like her in your school.)

In 1933, she used to teach classes on maths, geometry, and philosophy in the small French village of Roanne. Weil was one of the most unorthodox teachers at this school. She used to take her pupils outside and teach her classes underneath a cedar tree. Instead of looking for answers to the problems of geometry, Weil urged her students to actively find new problems. They had to look at geometry as a whole and immerse themselves in every detail of their subject, instead of narrowing their minds by concentrating on a single problem. She refused to give her students any grades because she thought that grades distract and narrow down one’s approach to the world. When you grade your students you shift their attention from great subject such as maths to minor bureaucratic elements such as grade.

In sum, Weil’s primary task wasn’t to teach them geometry, her primary task was to teach her pupils to pay attention to geometry.

III. ‘Paying attention’ as a spiritual exercise.

The purpose of true philosophy is to give you a set of spiritual exercises so you can sculpt your better self. Philosophy gives you tools to change how you see the world, and thus change yourself.3

The Roman philosopher-king Marcus Aurelius kept a journal of his spiritual exercises. Today this journal is known as Meditations. ‘The happiness of your life depends upon the quality of your thoughts.’ - Marcus reminds himself. If we paraphrase this quote, we can get what Weil writes in her notebook: ‘You read the world through the prism of your inner values’

There are striking similarities between Weil’s journal and Aurelius’s Meditations. For example, neither of them mentioned anything about contemporary events that surrounded them. If you don’t know who Marcus Aurelius is, you will never guess that he was Roman, or that he was an emperor, or that he lived 2000 years ago when you read his Meditations. It’s the same with Weil’s journals.

She fought against Franco’s forces in the Spanish Civil War; she took part in the French resistance organisations during the Nazi occupation of France, but if you open her journals and read them you will never know whether she was a contemporary of Marcus Aurelius or a Spanish resistance fighter of the 1930s.

Weil’s journals are also full of spiritual exercises. In one entry, she writes:

‘Never put something off indefinitely, but only to a definitely fixed time. Try to do this even when it is impossible. Exercises: decide to do something no matter what, and do it exactly at a certain time.’

In another note, she tells herself:

“Never surrender to the flow of time… allow yourself only those feelings which are actually called upon for the effective use or else are required by thought for the sake of inspiration.”

For Weil, life is a continuous sculpting of one’s inner world by learning how we can outgrow our selfish reflexes. To withdraw yourself from life and then reflect upon it is the way we can learn how to pay true attention.

IV. The highest forms of attentiveness: compassion and reverence.

In 2016, I used to live in one of the areas of north London. Every morning, on my way to work, I used to see a homeless man sitting on the cold floor reading a book. In front of him, he had one of those disposable coffee cups where you could throw some spare change if you cared.

He sat there every day and every day he read. He never got distracted from his book unless he had to thank someone for giving him money.

As a bibliophile, I always tried to look at what sort of books he reads when I leaned to drop some change in his cup. It seemed he read everything he could get his hands on and one day I asked him if there was a book I could buy for him. He told me that he would love to read Stephen Fry’s book on myths that was released around that time.

I bought him the book and I could see true joy on his face when I handed it to him the next day. I’ve to say I did this unconsciously. Only a book lover knows how solitary reading can be. Bibliophiles are in constant search for kindred spirits and that homeless man was a kindred spirit to me.

Weil would say that what I was doing was a form of paying attention. For her, compassion is one of the highest forms of attentiveness.

Attention is "the rarest and purest form of generosity." The act of giving oneself-turning away from one's own self and turning toward the world, making a place for others by placing one's own self in a subordinate position- is true attention.

Attentiveness entails the difficult task of waiting, not for the world to take note of us, but for us to take note of the world.

Another high form of attention according to Weil is reverence. She borrows the concept of Achtung which was developed by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant in his work on the metaphysics of morals.

Achtung is awareness. It is a form of attention that happens when we register the embodiment of the universal moral law in someone.

There are moments when another's gesture or word marks our lives; it commands our respect; it demands our reverence. The presence of Achtung, Kant writes, makes us "worthy of humanity."

Reverence is an important part of our lives because it reveals to us that there is something deeper in life than ourselves. It reveals to us that there is something other than ourselves that is real. Only through attentiveness one can notice the depth and meaning that surrounds us.

V. Attention & Meaning of Life

The Spanish Catholic priest St.Ignatius of Loyola wrote that the disturbed mind resembles a fly trapped in a glass. It flies up and down; to the left and right; without any particular purpose, without knowing where exactly it’s flying.

I find this metaphor to be so precise when it comes to the description of my mind. My mind sometimes flies from one book to another, from one ambition to the next, like a fly trapped in the glass I don’t know where I’m headed sometimes.

Loyola, same as Marcus Aurelius before him and Simone Weil after him, had his own set of spiritual exercises. In fact, all great thinkers that you can think of trained their minds in one way or another.

I’m no great thinker. I’m just a man who enjoys reading thoughts written by my dead friends like Simone Weil. But, this dead friend taught me to never let my experiences become mere reflexes. Weil taught me that true attention is a search for meanings, for different ways of looking at the world.

She taught me the meaning of true learning, true compassion, and true reverence. Weil told me that this triumvirate is the highest way we can pay true attention to the world.

I’ve been keeping a journal for the past fifteen years and most of my entries differ significantly in their style and purpose from the entries of Weil.

I’ve to say, however, that as time passes, and as I grow older, the pages of my journals are seeing more and more of spiritual exercises similar to the great thinkers such as Weil and Marcus Aurelius. As my attentiveness increases so does my desire to fix my inner faults and the way I read this world.

For example, the great American psychologist William James defined ‘attention’ as "taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalization, concentration, of consciousness is of its essence. It implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others."

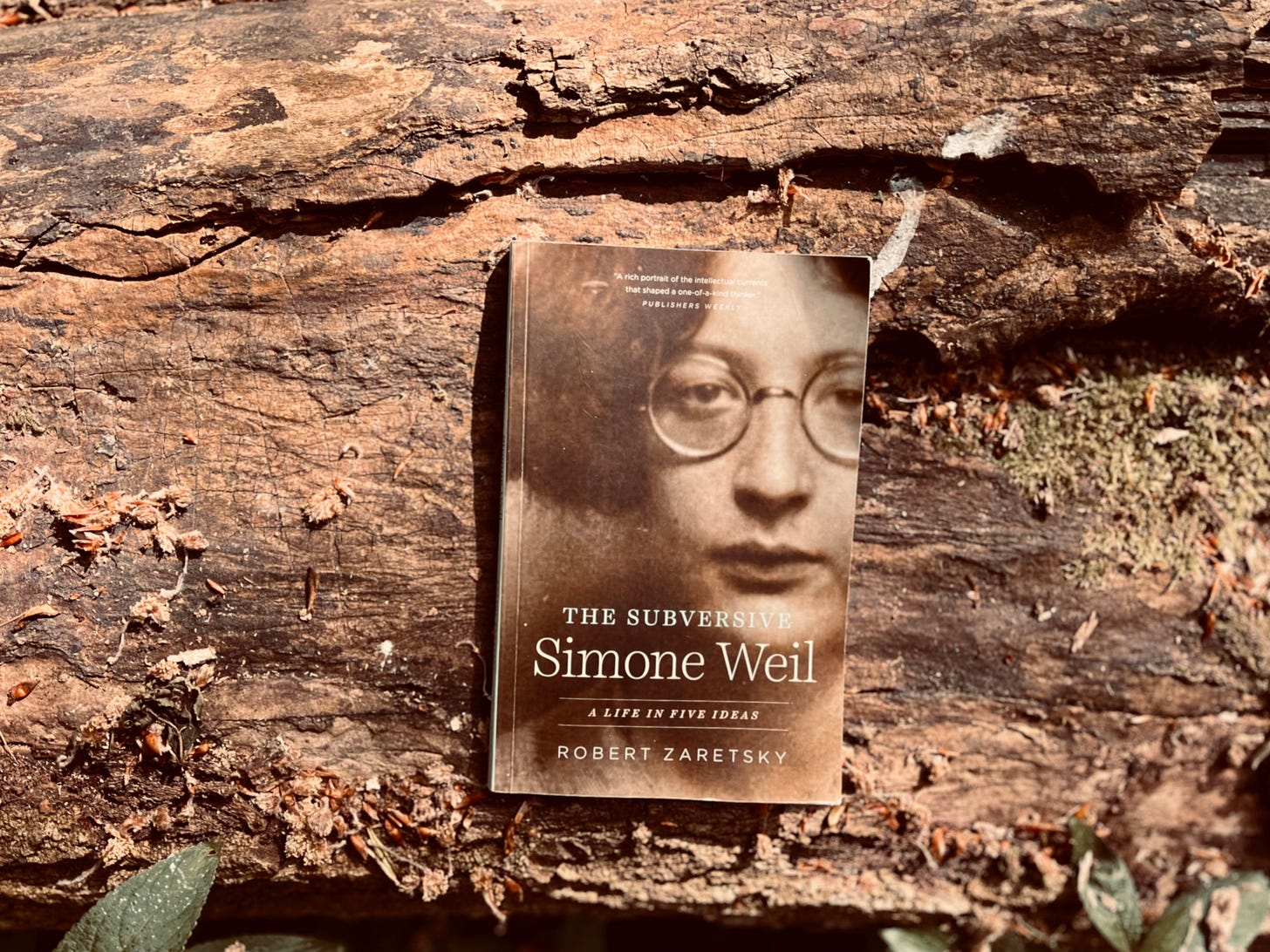

Zaretsky, The Subversive Simone Weil, 44

If you have to read just one book on philosophy in your lifetime, please read Pierre Hadot’s magnificent book ‘Philosophy as a Way of Life: Spiritual Exercises from Plato to Foucault’.

oh Vashik! your article is pure food for my soul and mind in this moment. Al my life I have been an avid reader, going from one book to another, from one interest to another. I am curious about everything. I think this is why I really understand the need (for me) of Paying Attention and Spiritual exercises as Veil and St Ignatius presented them. And thank you for introducing Veil´s work to me. I didn´t know her. Greetings from Peru!

Hey, dear Vashik, I will repeat Alejandra's expression. You provide our spiritual food, indeed. As for Veil, unfortunately, she is an unknown author to me too, but I will look for her writings now.

Thanks, Vashik!!!