Stoicism of Purgatory: In doing nothing men learn to do evil.

(Purgatorio, Canto I): Love, Virtue, Cato the Younger

In doing nothing men learn to do evil.

~ Cato the Younger

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

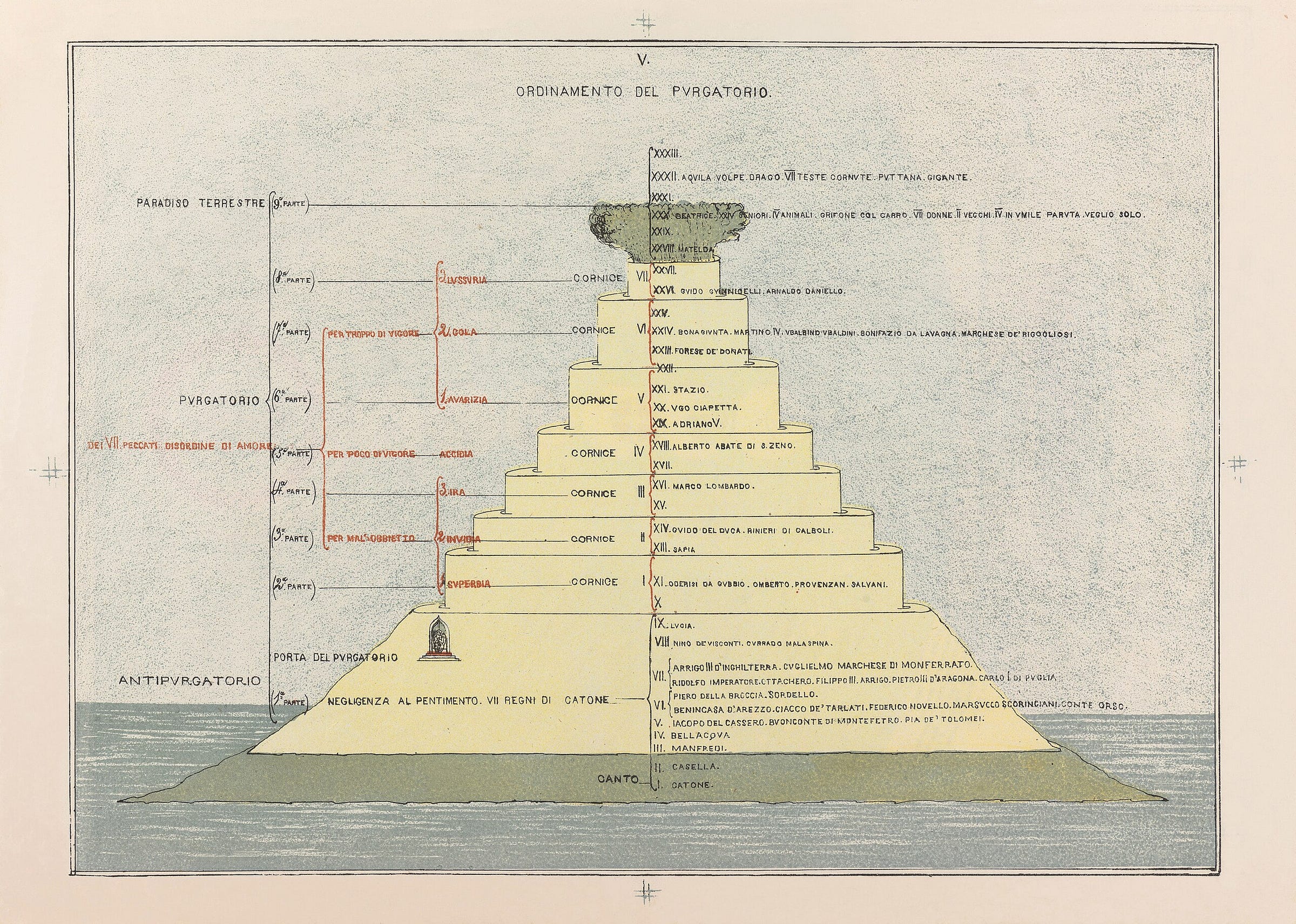

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this First Canto of the Purgatorio, we arrive at the base of Mount Purgatory and meet Cato, guardian of the realm. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

The invocation to a new realm - The hour before the dawn - Dante and Virgil at the base of Mount Purgatory, rising from the sea - The four stars and the radiance of Cato, guardian of Purgatory - Virgil requests permission to enter - The reed girdle and the cleansing of the stain of sin with dew.

Canto I Summary:

Hell is the fleeing deeper into the iron-bound prison of the self…Purgatory is the resolute breaking-down, at whatever cost, of the prison walls, so that the soul may be able to emerge at last into liberty and endure unscathed the unveiled light of reality.1

We can breathe the fresh open air of the waters, see the broad expanse of the heavens in the hour before dawn, and be filled with a sense of expansive hopefulness at the journey ahead, after the oppression of atmosphere and heavy gravity from which we have just come. We have arrived in Purgatory, less a place of punishment and more a place of voluntary purification.

The Inferno may fill one with only an appalled fascination, and the Paradiso may daunt one at first by its intellectual severity; but if one is drawn to the Purgatorio at all, it is by the cords of love, which will not cease drawing till they have drawn the whole poem into the same embrace.2

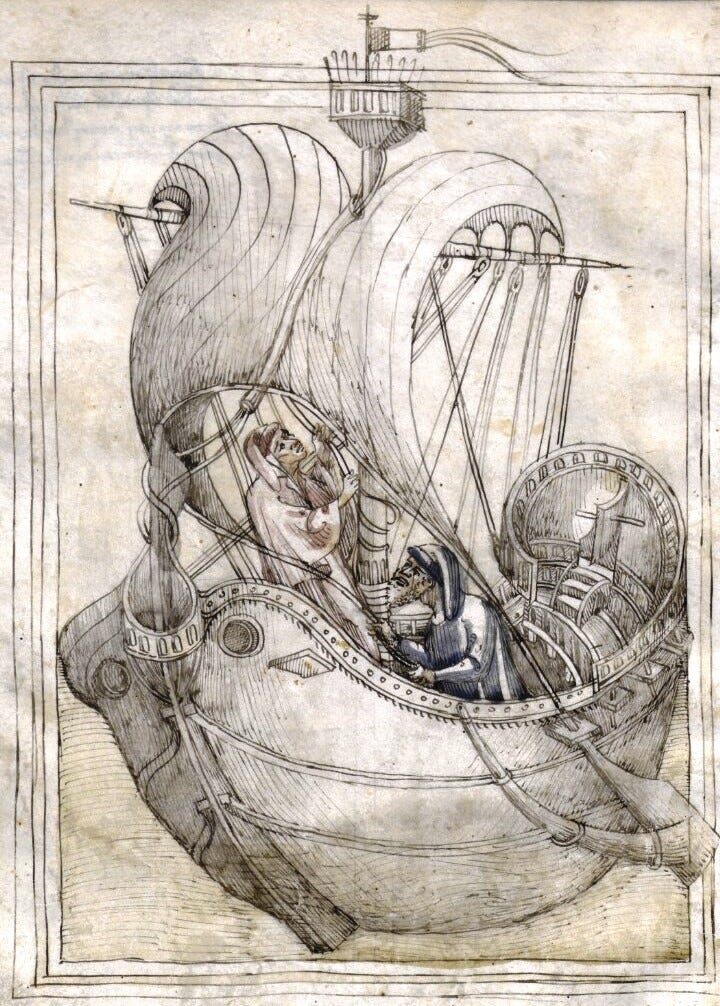

Dante acknowledges this fresh and favorable wind as he embarks on the second phase of his great Commedia, with a joyful, forward motion that leaves the sins and suffering of Hell behind.

There is a guaranteed cleansing and ascent before them, there is movement in Purgatory, where in Hell there was immobility of station and place even among the chaotic movement of the tortured souls in their agonies. Virgil, in his poetry, also sang of these sails metaphorically:

And in truth, were I not now hard on the very close of my toils, furling my sails, and hastening to turn my prow to land, perchance too, I might be singing what careful tillage decks rich gardens, singing of the rose-beds of twice-blooming Paestum.

Virgil Georgics iv.116-119

Dante makes his invocation to this new song:

But here, since I am yours, o holy Muses,

may this poem rise again from Hell’s dead realm;

and may Calliope rise somewhat here,

accompanying my singing with that music

whose power struck the poor Pierides

so forcefully that they despaired of pardon.

i.7-12

Calliope is the Muse of epic poetry - one of the nine sisters, patrons of the arts, to whom the poets and artists of old called upon for inspiration. We have heard Dante call out to them before. (Inferno ii.7-9, xxxii.10-12)

Do thou, O Calliope, thou and they sisters, I pray, inspire me while I sing.

Virgil, Aeneid ix.525

The Pierides (11) were the nine daughters of King Pierus who grew presumptuous of their talents, being named after the Muses, and challenged them to a singing contest. For their insolence, they were changed to magpies, birds who could only imitate the human voice. The humility necessary to enter Purgatory was lacking in these nine.

The Muse was speaking still when in the air

A whirr of wings was heard, and from high boughs

There came a greeting voice. Jove's child looked up

To see whence came the tongue that spoke so clear,

Thinking it was a man. It was a bird:

Nine of them there had perched upon the boughs,

Lamenting their misfortune, master-mimics,

Nine magpies.

Ovid, Metamorphoses v.294-301

After this invocation, Dante brings us to the scene before him; the sky before sunrise with its lovely colors, and the sight of Venus signaling the theme of Love that is encountered all throughout Purgatory. It is only through the love of virtue that the cleansing offered here can be obtained.

It has been well said by a great saint3 that the fire of Hell is simply the light of God as experienced by those who reject it; to those, that is, who hold fast to their darling illusion of sin, the burning reality of holiness is a thing unbearable.4

They are in the southern hemisphere, directly opposite Jerusalem in Dante’s conception of the world, all water but for the massive Mount Purgatory. Dante turns to look toward the south; As he looks, he sees four stars, symbolic of the four cardinal virtues; prudence, temperance, justice, and fortitude.

In the architecture of Mount Purgatory, which we will come to know as well as we got to know the nine circles of Hell, the topmost terrace is the place of the Earthly Paradise, or the Garden of Eden. The first people that Dante references as having seen these four stars, as well as being the only ones ever to see them while living, were Adam and Eve before they were cast out of the garden. Upon their expulsion, they arrived in the Northern Hemisphere, in Dante’s vision of events. No one in the Northern Hemisphere can see these stars.

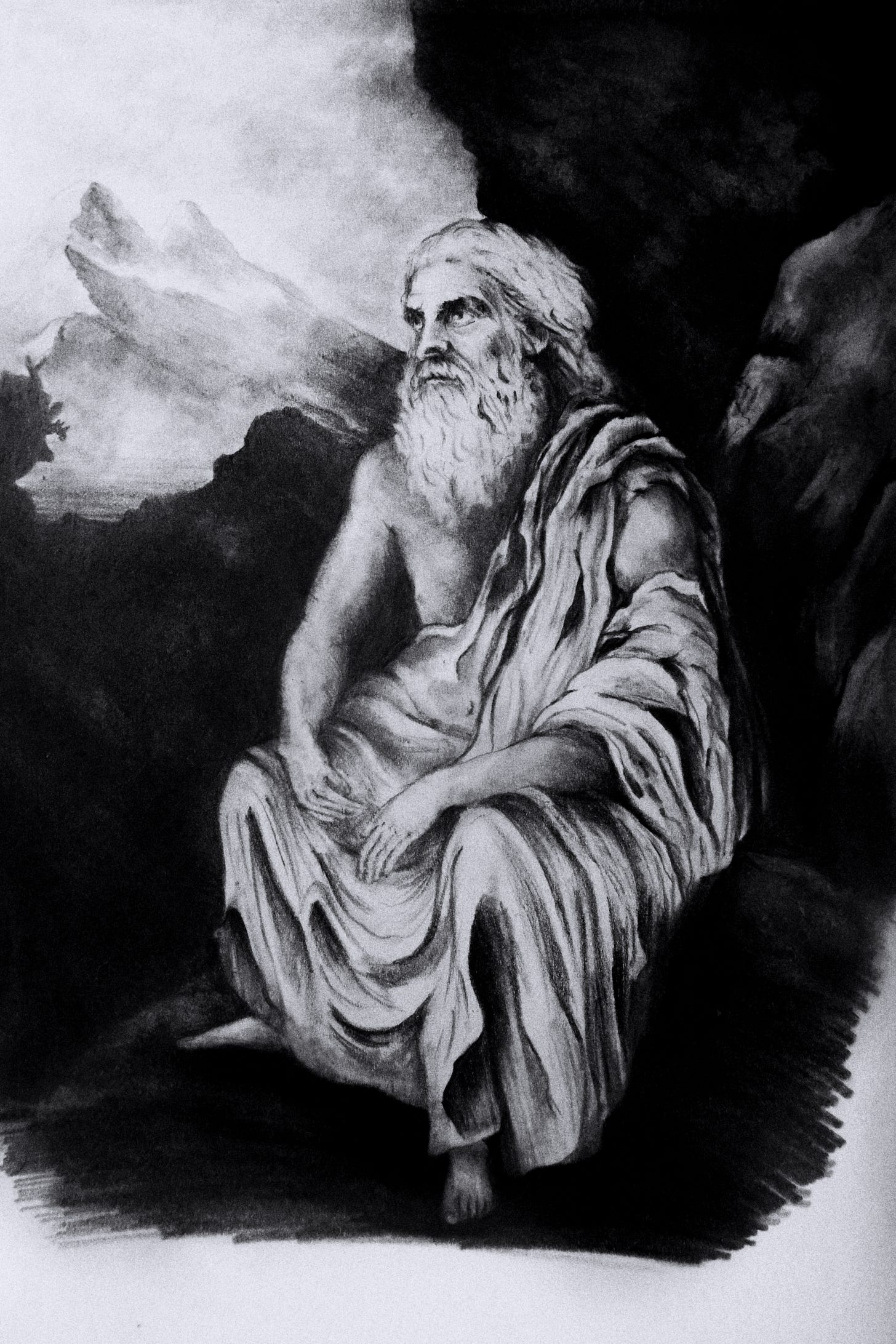

As he looked away, and toward the constellation of Ursa Major, the Big Bear, a man appeared.

I saw a solitary patriarch

near me - his aspect worthy of such reverence

that even son to father owes no more.

The rays of the four holy stars so framed

his face with light that in my sight he seemed

like one who is confronted by the sun.

i.31-33; 37-39

The first figure they meet is Cato, the Guardian of Purgatory. Representative of outstanding virtue in antiquity and the middle ages, Cato the Younger guards Purgatory as he guarded a natural morality in his actions in life.

A tribune in Rome and of the aristocracy, he sided against Caesar in the Civil War, and rather than submit to his tyranny, he committed suicide; a noble act in the Stoic school of which he was a strong proponent. It is said that he spent his last hours reading Plato’s Phaedo on the immortality of the soul.

This was the character and this the unswerving creed

Of austere Cato: to observe moderation, to hold to the goal,

To follow nature, to devote his life to his country,

To believe that he was born not for himself but for all the world.

In his eyes to conquer hunger was a feast, to ward off winter

With a roof was a mighty palace, and to draw across

His limbs the rough toga in the manner of the Roman citizen of old

Was a precious robe.

Lucan Pharsalia ii.380-87

As the lights of the four stars of cardinal virtues shine upon his face, Cato was illumined by their radiance:

The rays of the four holy stars so framed

his face with light that in my sight he seemed

like one who is confronted by the sun.

i.37-39

Cato was in disbelief to see Dante and Virgil arrive from an impossible way, from Hell itself, and he questioned the very nature of divine law that would make such a thing possible. Virgil motions for Dante to kneel in reverence, and to bow his head to indicate his humility and willingness.

Virgil tells Cato that their mission is a divine one, sanctioned by Beatrice herself from the high regions of Paradise. He explains the nature of their journey and that Dante is still a living soul.

I showed him all the people of perdition;

now I intend to show to him those spirits

who, in your care, are bent on expiation.

i.64-66

Virgil acknowledges Cato’s guardianship and asks for welcome to travel through his realm. Cato found death in Utica when he took his own life — the prominent north African city to which he retreated after Pompey’s defeat — and there shed his mortal body for freedom, but there is more to his position; such is Cato that he will be sent to Paradise upon Judgement Day, and gain the body of light and immortality for his virtue and his work. Dante has given Cato a most noble distinction.

Virgil guarantees Cato that they have not transgressed the divine law in their journey, and that he has come from Limbo, where Cato’s wife Marcia still resides. He implores Cato to remember his love for her to soften his heart towards them, and to let them journey the seven terraces of Purgatory.

Cato remembers Marcia, now separated by the great gulf that divides Hell from the other realms, a gulf that cannot be crossed. He can no longer be moved by the passionate side of love in regard to thinking about her, but their mission as sanctioned by Beatrice is enough for him to let Dante and Virgil through.

Marcia and Cato’s background is worth noting; they had been married with children when, due to circumstances surrounding Cato’s political safety, they divorced and Marcia married their friend Hortensius. Upon Hortensius’ death, Marcia came back to Cato and they remarried, never having fallen out of love. In Dante’s Convivio, he uses the example of Cato and Marcia as the soul’s journey back to God in later years.

Go then, but first

wind a smooth rush around his waist and bathe

his face, to wash away all of Hell’s stains;

for it would not be seemly to approach

with eyes still dimmed by any mists, the first

custodian angel, one from Paradise.

I.94-99

Dante must prepare himself for the atmosphere of Purgatory; he must put on the reed belt of humility and cleanse his face from the tears and stains of Hell which cloud his vision. They are at the base of Mount Purgatory, and as they climb, will come to the first angel at St. Peter’s gate, through which they will be in the first terrace.

Cato points them to the shore, where they will find the reeds growing - pliant reeds that bend with the waves of the shore, just as Dante must bend with humility to make his way through Purgatory. This cord will be in contrast with that girdle that Dante threw over the edge leading down to the eighth circle of Hell, calling Geryon up as their transport over the cliff.

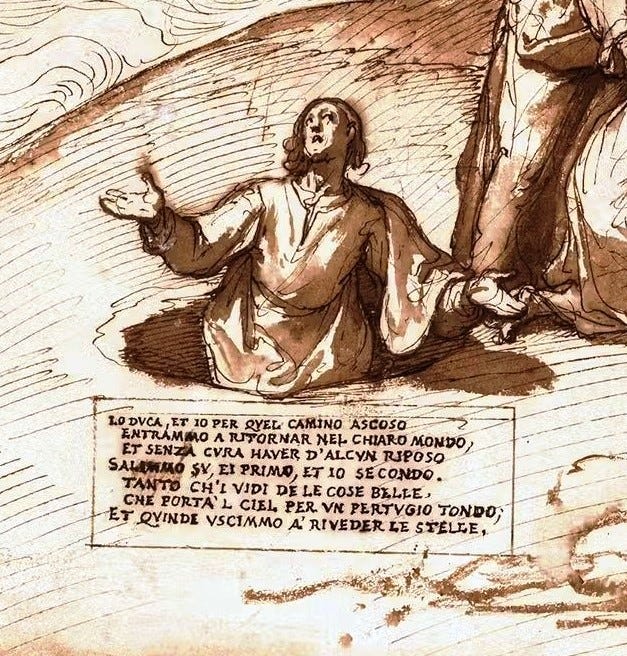

Cato vanished, and Dante stood from his position of supplication that he held during Cato and Virgil’s discourse. They made their way down to the shore where the reeds grew and the dew still rested cool upon the grass in the shade before the sunrise. Like a baptism, Virgil cleansed the stain of Hell from Dante’s face

My master gently placed both of his hands —

outspread — upon the grass; therefore, aware

of what his gesture and intention were,

I reached and offered him my tear-stained cheeks;

and on my cheeks, he totally revealed

the color that Inferno had concealed.

i.124-129

As Virgil picked a reed to tie around Dante’s waist, another grew back in its place. This reed is like a passport to this realm, just as when Aeneas had to find the Golden Bough in order to present it to Persephone as a token to be able to pass into the Underworld on his journey. They are now prepared for what lies ahead.

On a dense dark tree lurks a hidden

Bough, and its leaves and its pliable, willowy stem are all golden,

Sacred, they say, to the underworld’s Juno.

No one’s permitted descent beneath earth’s deep mantle without first

Harvesting this gold-tressed live growth from the tree where it’s nurtured.

This is the gift you must steal, fair Proserpina rules, as her tribute.

Aeneid vi. 136-138; 140-142

💭 Philosophical Exercises

Consider in silence whatever any one says: speech both conceals and reveals the inner soul of man.

~ Cato the Younger

Bear in mind, that if through toil you accomplish a good deed, that toil will quickly pass from you, the good deed will not leave you so long as you live; but if through pleasure you do anything dishonourable, the pleasure will quickly pass away, that dishonourable act will remain with you for ever.

~ Cato the Younger, quotes by Aulus Gaellius

We carry within ourselves the fragments of our victories and the lessons of our defeats. They become part of our psyche. Heracles, for example, after slaying the Nemean lion, skinned his foe and wore its legendary impenetrable hide as his own armor. Likewise, after conquering the Lernaean Hydra whose blood was laced with poison he dipped his arrows in it, turning the creature’s deadly nature into his weapon.

But perhaps the most profound example is the myth of how Perseus slew the Gorgon Medusa. With the help of Athena’s polished shield, Hermes’s winged sandals, and Hades’ helm of invisibility, Perseus triumphed over the monstrous guardian. His trophy was Medusa’s severed head, which, even in death, had retained its power to turn those who looked upon it into stone.

What is most curious, however, is that Perseus later returned Medusa’s head to Athena, goddess of wisdom, who then integrated it into her shield.

My reader can now see where I am leading both of us. Perseus first had to conquer Medusa with the divine gifts bestowed upon him by the gods. But after defeating her, he didn’t discard what he had overcome, instead, he integrated his conquest by using her petrifying head as a weapon. At some point, knowledge, when applied to real life, becomes part of who we are. It becomes wisdom.

This is precisely what the first canto of Purgatorio is concerned with.

I. Why many readers stop with Inferno?

They say most readers of The Divine Comedy stop at the Inferno. In one London bookshop, for example, I saw an entire shelf lined with various editions of Inferno, each with its own enticing cover art and yet, not a single copy of Purgatorio or Paradiso in sight.

How can we explain this? Why would a reader who has witnessed the horrors of Hell not wish to know how to move further away from that dreadful place? How to ascend toward Paradise?

Perhaps some believe that once pain and suffering are over, happiness will naturally follow. But the absence of suffering does not guarantee joy, contentment, serenity of soul, or clarity of mind.

It is one thing to be lost in a dark forest, and quite another to escape it and still not know where to go.

Philosophers such as Aristotle, whose influence on Dante is profound, and later Otto Weininger, believed that before one can pursue virtue, one must bring order to one’s rational mind. That, after all, is the purpose of psychology: psyche and logos (soul and ‘rational word’), aligned. The purpose of Inferno was to show Dante how disordered and disoriented the state of his mind was. This is why Virgil represents our reason after all, only through reason we can reach Logos and bring pieces of our scattered mind together.

Dante and Virgil emerge from Inferno. And it is fair to say, dear reader, that we are emerging with them. For, to borrow Dante’s own words, we are “leaving behind ourselves a sea so cruel.”

The best way I can illustrate why we must continue our journey and not stop or even pause here is by asking my reader to imagine traveling with a faulty compass, one that doesn’t point north, or perhaps doesn’t point anywhere at all. That was our condition before descending into Inferno. Now, after enduring its trials, our compass is finally repaired. And yet, we still do not know where we are going. It is terrifying to find yourself in the middle of the ocean with a broken compass but it is just as terrifying to have a working one and no map, no direction.

Many readers confuse the repaired compass with the final destination and they choose to stop their journey.

II. Aristotle: Four tools that can help you reach wisdom and meaning (You already have them)

Perhaps one of the many reasons why readers stop at Inferno lies in its sheer intensity. One needs to catch a breath before continuing. That is why Dante now invokes a Muse, just as Homer and Virgil did before him, and as Milton would later do in Paradise Lost. He calls upon Calliope, the Muse of epic poetry, the most powerful among them all - rivalled perhaps only by Mnemosyne, the Muse of Memory.

But Calliope is going to help Dante tell his story further to us, who then helped Dante to continue the journey further upwards?

The lovely planet that is patroness

of love made all the eastern heavens glad,

veiling the Pisces in the train she led.

That planet is of course Venus and the Pisces represents Christianity, this is beautiful and yet predictable, what is mind-blowing is the following:

After my eyes took leave of those four stars,

turning a little toward the other pole,

from which the Wain had disappeared by now,

Some of the most respected commentators on Dante—such as Singleton, Hollander, and Reynolds—agree that the four stars he refers to represent the Southern Cross. But how could Dante have known about them, given that they were unknown in Europe at the time? Some scholars suggest that Dante may have, somehow (though this remains unconfirmed) encountered Marco Polo, one of the first to describe them.

The four stars traditionally symbolise the cardinal virtues: prudence, fortitude, justice, and temperance. According to the Aristotelian view, these virtues are not learned but innate, we are born with the capacity for them. This does not mean that everyone is born just, but rather that all human beings possess an innate drive toward justice, even if, in believing ourselves just, we may be deeply mistaken.

Thus, Dante the poet suggests that through Love (symbolised by the planet Venus) and by cultivating the four cardinal virtues, we may find our path to salvation, or what Aristotle called eudaimonia: a state of harmony with the world achieved by fulfilling our innermost potential.

III. Cato: Bitter are the roots of study, but how sweet their fruit.

What my reader has noticed here is that for the first time, the entrance to a new realm is kept not by a devilish figure or a beast but by a man, a bearded and wise man. The name of this man is Cato of Utica, or as he often is called Cato the Younger.

There is a magnificent book about him called Rome’s Last Citizen for those of you who are curious to dive into this remarkable figure who was a role model for almost (if not all) founding fathers of the United States. His biography by Plutarch is also brilliant, short and worth your attention.

Cato was a Roman senator who embodies the true freedom and virtue. He opposed Caesar and did everything in his power to stop the fall of the Roman republic.

When Dante and Virgil meet Cato of Utica, the great Roman poet describes the state of Dante prior to entering Inferno as this:

This man had yet to see his final evening;

but, through his folly, little time was left

before he did—he was so close to it.As I have told you, I was sent to him

for his deliverance; the only road

I could have taken was the road I took.

Does Virgil mean that Dante was on the verge of taking his own life when he was in the dark forest?

The parallels here are striking: when Julius Caesar overthrew the Roman Republic and declared himself emperor, Cato chose to take his own life rather than submit to a tyrant.

Cato famously declared: “I know not what treason is, if sapping and betraying the liberties of a people be not treason.” This statement draws a powerful connection between the traitors of the Inferno and the moral bridge Dante constructs toward Purgatory. Cato chose suicide not out of despair, but as a final act of fidelity - refusing to become complicit in Caesar’s tyranny. To live under the usurper, for Cato, would have been nothing less than a betrayal of the Republic.

Cato’s character, in my interpretation, embodies the very philosophy of Purgatory. He was like a moral compass, attempting to guide the collapsing Roman Republic back to its virtuous foundations—just as the soul, in Purgatory, is guided back to the right path. Unlike Inferno, where we were told to abandon all hope, here hope remains—if we learn to make virtuous choices.

IV.

Returning to our idea of integrating our experiences in the manner of Heracles and Perseus, what Cato tells our companions to do before they could proceed in their journey is to cleanse themselves from the filth and dirt they brought from the abyss.

Those verses are incredibly beautiful:

When we had reached the point where dew contends

with sun and, under sea winds, in the shade,

wins out because it won’t evaporate,my master gently placed both of his hands—

outspread—upon the grass; therefore, aware

of what his gesture and intention were,I reached and offered him my tear—stained cheeks;

and on my cheeks, he totally revealed

the color that Inferno had concealed.

Virgil washes away Dante’s infernal tears. Reason cleanses us from pain. How beautiful and how profound.

What Cato suggests is not forgetfulness, but purification. Virgil washes Dante so that he may see clearly again. What we experienced in the Inferno has already become part of our character, just as Medusa’s head became part of Athena’s shield.

Let us wash away our infernal tears, dear reader, so we can continue on toward the greater journey that lies ahead.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Cato rebukes Virgil

Virgil is a wise guide, and yet we are reminded that he is a pagan. His attempt to persuade Cato draws on personal ties, he mentions Marcia, Cato’s wife, who now resides in Limbo with him. In doing so, Virgil offers a kind of emotional bribe in exchange for passage. But Cato firmly rebukes him, declaring that divine intervention from the highest authority is the only command he recognises.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

I have inscribed the last words of Inferno into a wall of my library: Emerge to see the stars again!

When we had reached the point where dew contends

with sun and, under sea winds, in the shade,

wins out because it won’t evaporate,my master gently placed both of his hands—

outspread—upon the grass; therefore, aware

of what his gesture and intention were,I reached and offered him my tear—stained cheeks;

and on my cheeks, he totally revealed

the color that Inferno had concealed.(121-129)

Sayers Purgatory 16

Sayers Purgatory 9

St. Catherine of Genoa

Sayers 16