In one of his short aphorisms, the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer said:

‘Talent hits a target no one else can hit; Genius hits a target no one else can see.’

For the most of his life the Spanish painter Francisco Goya hit the targets no one else could hit. He came from a low-middle class family, but due to his exceptional talent he quickly became a painter at the 18th century Spanish court.

The Spanish nobility admired Goya for the beautiful portraits he painted of them. But for Goya, the admiration of aristocrats and the wealth it brought to him was not enough. In one of the letters to his friend — Don Martín Zapater with whom Goya corresponded for over 30 years, he wrote:

I tell you that I have nothing more to wish for. They were extremely pleased with my pictures, and expressed great satisfaction not only the King, but the Prince as well. Neither I nor my works deserve such recognition.

His paintings didn’t deserve recognition, Goya thought, because there was nothing original or exceptional about those works. They did not have anything that distinguished them from the works of other also talented painters that lived in Madrid at the time.

Not too long after that letter to Zapater, Goya painted the annual festivity of San Isidro, Madrid’s patron Saint (you can see this at the top of this article).

Bright, warm colours depict the beauty, stability and customs of the Spanish society of the time. We can see an aristocratic gentleman courtly bowing in front of a lady at the front of the painting. In the middle of this scene we can see some carriages arriving to the festivity and people dancing to traditional music. And, of course, we can see domes of Madrid’s churches glowing under the sun. Everything seems the way it was at this time in Madrid and how, most of its inhabitants thought it would continue to last forever.

Three decades later, Goya paints the same place and the same day of the festivity. But in a different light.

Or, is it better to say — lack of light?

The ordered world is now disordered world. The darkness has swallowed the bright colours of Madrid. Goya drew this scene straight on the wall of the so called ‘House of the deaf’ outside Madrid, where he exiled himself at the end of his life.

In this scene, the citizens of once prosperous and peaceful Madrid can no longer hear the tunes of their favourite folk songs. Instead they listen to the noise of a discordant, untuned guitar played by a madman.

We can no longer see Madrid with its bright walls and domes behind the delirious crowd that Goya depicts here. All we can see, in far distance, are ruins of once beautiful city.

What caused this chaos? How could Madrid get absorbed by darkness in just 30 years?

Goya places the man who was responsible, ‘a criminal’ as he described him in a letter, right in front of us. This criminal, in the centre, looks straight into our eyes.

This man in the middle is the author of all this woe. His name is Napoleon Bonaparte.

In 1808, Napoleon’s forces invaded Goya’s motherland. Not long after the invasion, Napoleon’s own brother Joseph became the new king of Spain.

For the next few decades Goya witnessed not only violence that was unleashed by Napoleon’s invasion but also witnessed how his own compatriots were prepared to murder each other for petty political differences and greedy ambitions.

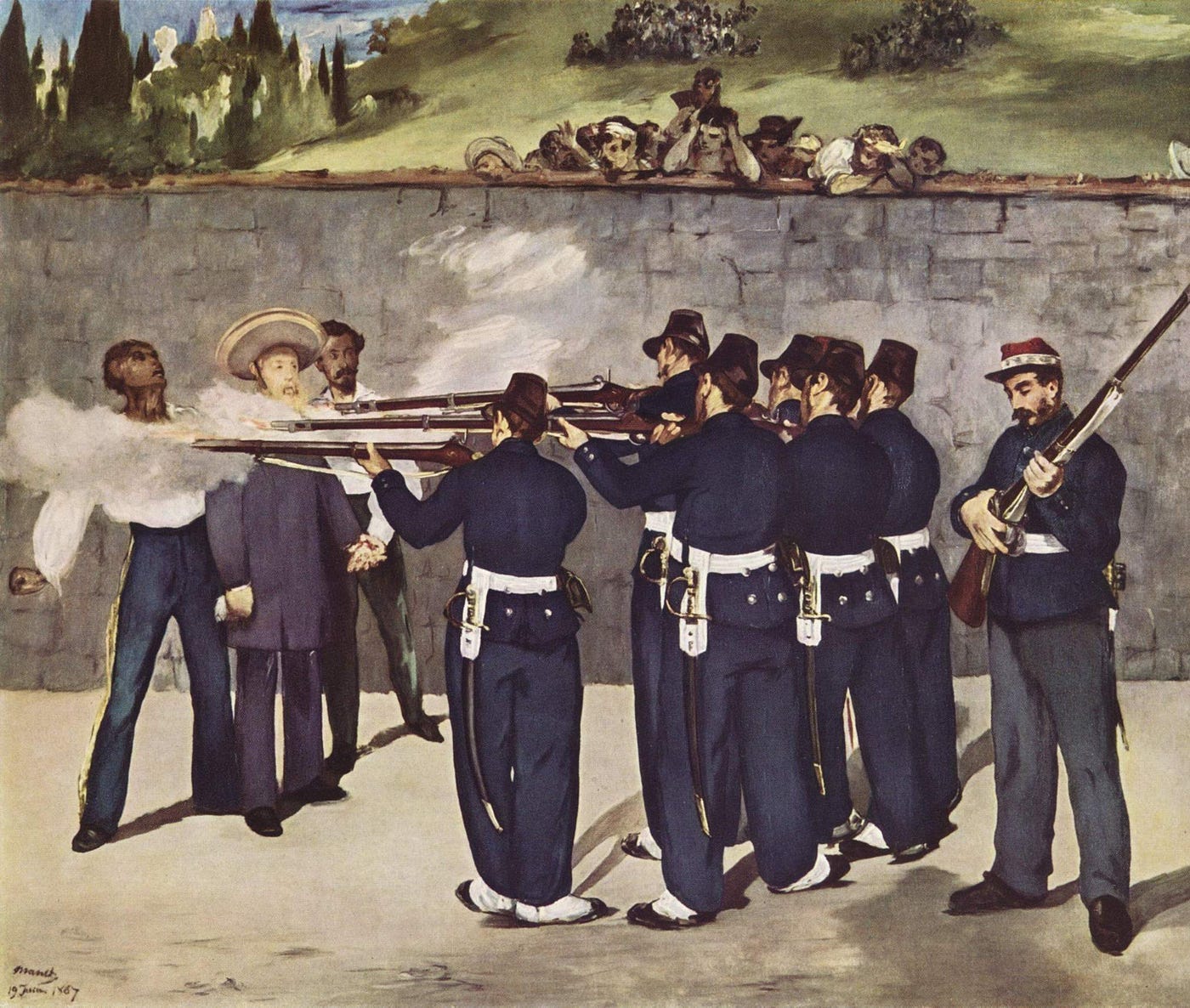

This darkness that surrounded Goya unlocked a hidden potential that slumbered inside him for most of his life. This is the time when Goya starts to ‘hit the targets no one could see’. He shocks his contemporaries by depicting the execution of Spanish resistance fighters by the French troops in 1808.

The art historian, Kenneth Clark, later labeled this painting as “the first great picture which can be called revolutionary in every sense of the word, in style, in subject, and in intention”

Later, Goya’s painting inspired Édouard Manet and Pablo Picasso, who expressed the horrors of their own time in imitation of Goya’s painting.

At this period of his life Goya’s health was slowly and agonisingly declining. He was also losing his hearing. We can only try to imagine what was happening with Goya’s mental health after witnessing the horrors of Napoleonic invasion and then being tortured by the pains inflicted by his own body .

Maybe it was the combination of these two sufferings that unlocked Goya’s unconscious and helped him create the painting that he is most known of — Saturn devouring his sons.

According to the myth, the titan called Cronos (in Roman mythology Saturn), feared that his own children would overthrow him, and ate each of them upon their birth.

There is a reason why Goya painted this particular myth. Its story was deeply allegorical to the events following the French revolution in 1789.

‘French revolution devours its own children’ — wrote a Swiss journalist — Jacques Mallet du Pan, who supported the royalist cause.

Goya knew what happened in France and knew about the consequences of the French Revolution. He knew that one day, you could be labeled the leader of the revolution and then the next day lose your head to guillotine because of being labeled the revolution’s traitor.

For Goya, French revolutionaries resembled to Saturn who devoured his own children.

This scene was depicted by masters before Goya. Most famously by Rubens — a painter who Goya admired and imitated at his early years — who also painted this scene.

Rubens’ depiction also inspires fear, but there is a large difference between the two works.

Rubens paints his Saturn as a Godlike and powerful being committing this horrific act.

Goya’s, in contrast is everything but Godlike. His Saturn is disfigured, featureless and chews his victim with the eyes full of madness.

No mythical or biblical god was depicted in such way before. Years later, one prominent art critic said: ‘Napoleon’s ambitions unlocked Goya’s genius’.

For the most of his life, Goya imitated the old-masters who he admired such as Rubens, Velazquez, Rembrandt. His imitations were exquisite and beautiful. They showed his talent, but Goya’s ambition was not to be a talented imitator, but to become someone who will later be imitated by the next generation of artists.

Art historians have tried to identify the exact moment when Goya stopped imitating old-masters and began to follow his inner vision. Yet, unable to do that, they have divided the life of Goya into ‘early’, ‘middle’ and ‘late’ periods. They understood, that it was impossible and unnecessary to pin down the exact time or the exact work that unblocked Goya’s genius. The path to genius and to ability ‘to see what no one else can see’ is a gradual process that needs time to grow and ripen in order to bear fruit.

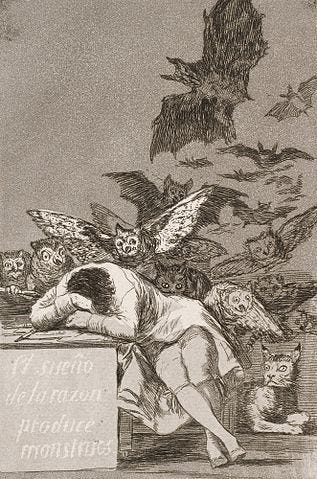

It might have started with the series of etchings called Los Capricios that Goya made in 1799 before the Napoleon’s invasion. These etchings were ignored by the public and were left under-appreciated by the critics.

However, a closer look at those works reveals the hidden roots Goya’s genius.

One of his etchings depicts a man who is hiding his face from bats and owls that fly around him.

On the side of the desk, where the man lied his head, Goya engraved a quote that says: ‘Il sueño de la razon produce monstruos’ or ‘the sleep of reason produces monsters’.

After Napoleon’s invasion Goya witnessed how the faculty of reason of his compatriots went slowly to sleep. He saw how this sleep of reason produced monsters that haunted his country. He witnessed how brothers turned against each other and how once friendly neighbours became enemies due to petty political differences. Ironically, it was this sleep of reason of his compatriots, which awakened the genius that was slumbering within Goya for most of his life.

One of the most prominent paintings that Goya produced was painted straight onto the plaster of the walls of his home (which locals referred to as the ‘House of the Deaf’) was the piece Duelo a garrotazos or Fight with Cudgels. He painted it between 1819–1823, and once again, Goya uses Greek mythology as an allegory to the events of his time.

It refers to a myth of Cadmus and the dragon’s teeth. In this story, Cadmus, the first king of Thebes, planted the teeth of a dragon into the ground, following instruction from the goddess Athena. From it sprang a race of strong men called Spartoi. To identify the strongest among this new race of men, Cadmus threw stones among them causing them to fall upon one another. After fierce battles only five of the Spartoi survived and later assisted Cadmus in founding the kingdom of Thebes.

On Goya’s painting we see how two Spanish farmers fight each other as fiercely as the race of Spartoi would have done in the myth of Cadmus. They seem to be floating in the air, while they try to swing their cudgels as hard as they can to hit one another. If we look closer, Goya stopped painting their legs below their knees. The legs of those two Spanish Spartoi are no longer touching their native land. For Goya, they have lost it the moment they surrendered their reason to the king’s provocation and began to fight each other. Like Cadmus, the leader of Spain at Goya’s time, threw stones at their own citizens, and the citizens whose reason was in a deep sleep, fell upon each other’s throats.

By the age of 75 Goya had produced fourteen paintings similar to Saturn and Fighting with Cudgels, in his ‘House of the Deaf.’ Painted straight onto the walls, he never intended them to be exhibited. Only a narrow circle of friends and family who visited him knew about these works. These images that have helped immortalise Goya and earn him the title of genius were meant to be kept a secret. Due to their depiction of dark and haunting scenes this series of paintings received a name of Black Paintings.

Fifty years after Goya’s death, they were taken down and transferred to be exhibited in the world-renowned ‘Museum del Prado’ in Madrid.

They remain there on display to this day. Millions of visitors enter the doors of the Prado Museum every year and many of them come to see Goya’s masterpieces. His earlier works though are largely being ignored by the crowd. It is the Black Paintings that art-lovers want to see. It is in Black Paintings that Goya’s genius sprang and it is due to them that his name is still remembered today.

article was originally published in January, 2021 on Medium.

I no longer write there, so thought I would share some of the pieces here.

Remarkable how traumatic happenings like Napoleon can produce such exquisite work. Sounds like a cliche, but it really is just a testament to humanity’s transformative powers, making even destruction an opportunity for beautiful creation.

Thank you for this!

To see what no one else can see … the horror of the world … There is no one in hell because all the demons are here.