The Gates of Hell Are Wide, Path To Heaven Narrow (Dante Read-Along)

(Inferno, Canto V): The Realm of Lustful: Paolo and Francesca

“True love is like ghosts, which everybody talks about and few have seen.”

~ La Rochefoucauld

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this fifth Canto we wake up in the second circle of Hell. You can find the main page of the read-long right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character and symbolism explanations.

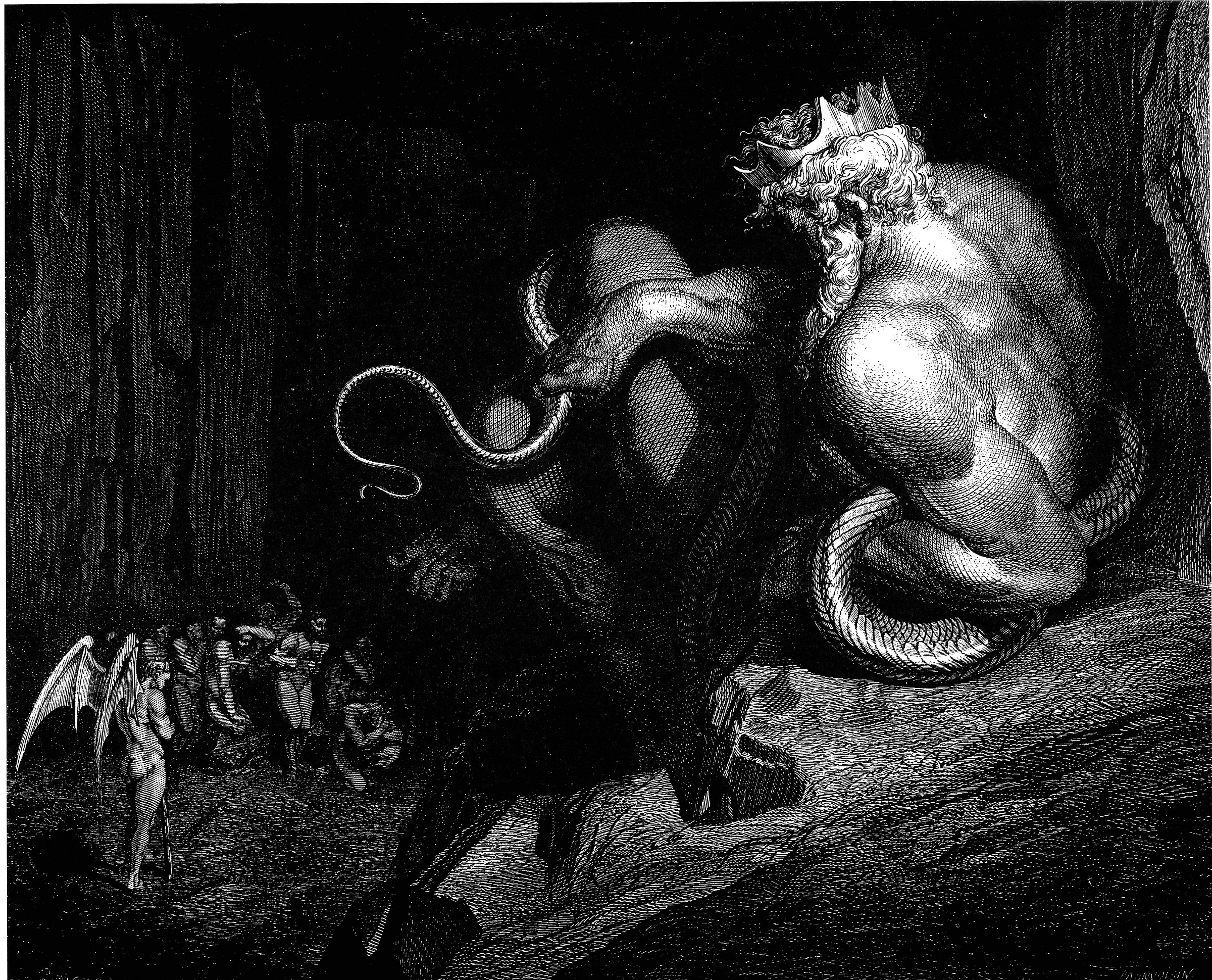

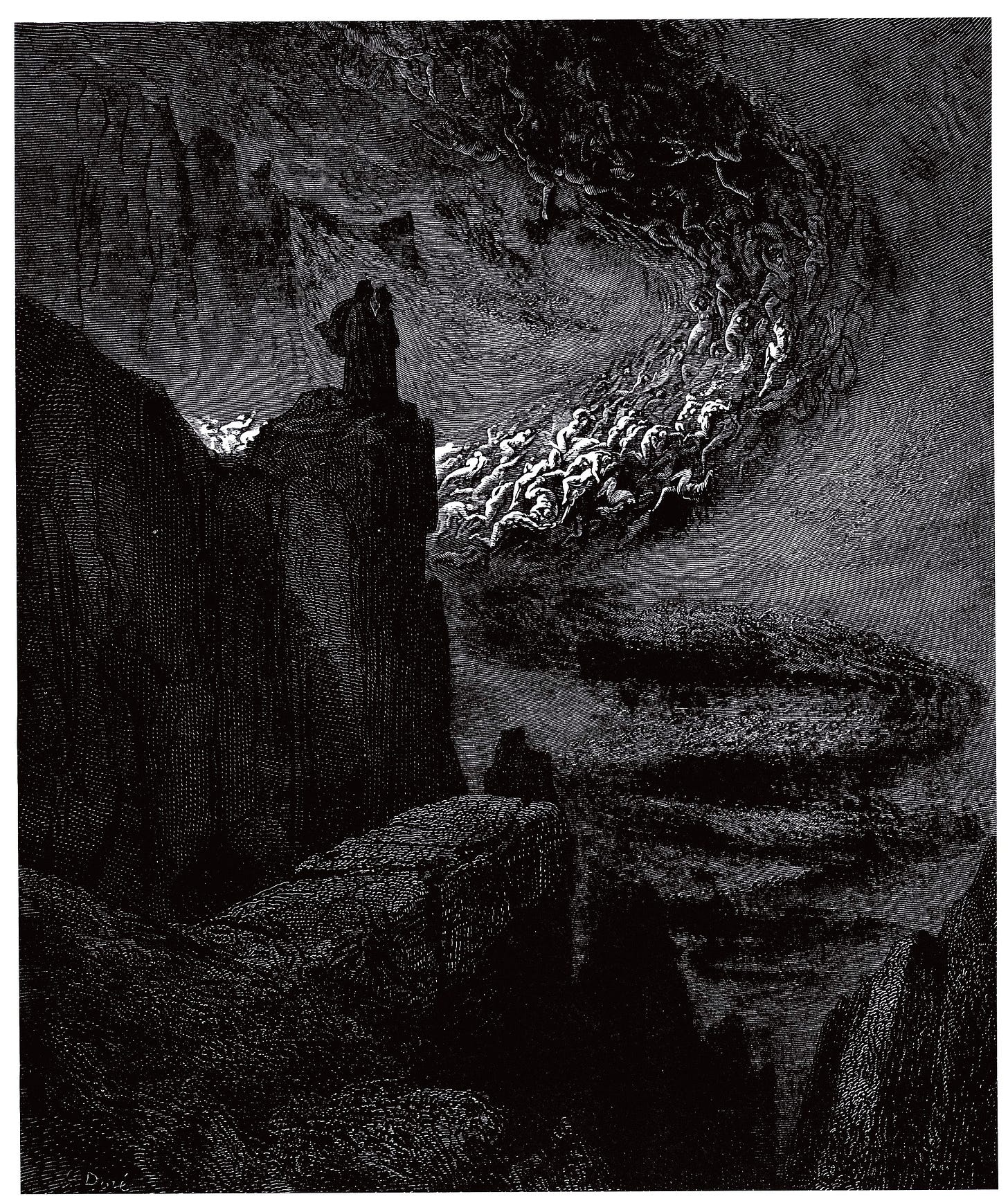

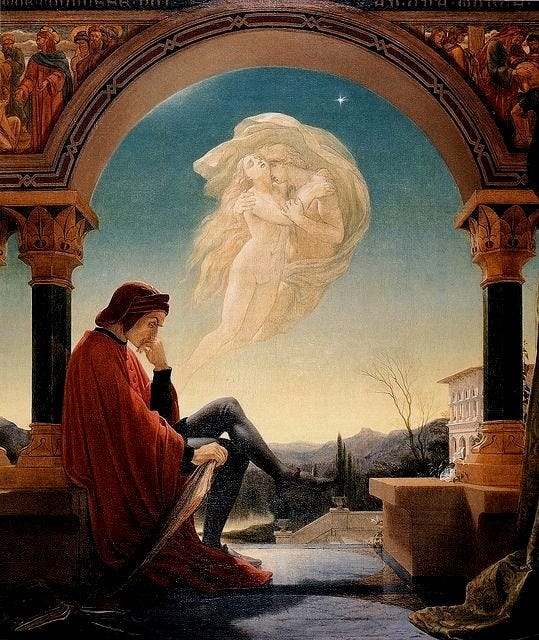

All wonderful illustrations are done specially for Dante read-along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Dante and Virgil enter the Second Circle - The realm of the Lustful - Minos the judge halts them and is rebuked by Virgil - The sinners are tossed in the terrible winds - They see famous lovers of the past - Dante speaks to one of the shades, Francesca da Polenta - She tells the story of herself and her lover Paolo Malatesta - Dante is so moved by passion that he faints insensibly

Canto V: Summary

Dante and Virgil descend into the second circle of the Lustful; this is the first of the four circles of Incontinence, or sins of self indulgence and lack of control over the passions. These sins of the leopard are in upper Hell, on the outer edges. These less impactful sins are aimed at the self rather than outward to others. This realm is also the place that we encounter actual punishment of sin, rather than a holding place, such as the Vestibule of Hell or of Limbo. As we progress, the degree and intensity of the sin merits greater punishment with each progressive level.

The first thing that the pilgrim and poet encounter upon entering this first realm of punishment of sin is in meeting Minos, the judge, the legendary King of Crete. Here in Hell, there is “self knowledge” of sin, an awareness and full understanding of the wrong done, so the soul confesses itself to Minos, Minos does not have to do the condemning.

Virgil explains this to Dante:

I mean that when the spirit born to evil

appears before him, it confesses all;

and he, the connoisseur of sin, can tell

the depth in Hell appropriate to it

V.7-10

Virgil also places Minos as a judge in the Underworld in his Aeneid:

Placement here’s not assigned without lot or a process of judgment.

Minos presides in a court, shakes lots in an urn, summons silent

crowds for a hearing, investigates lives and the charges against them.

Aeneid VI.431-433

Minos stops the living Dante with a warning, but Virgil, as with Charon, rebukes him with the knowledge that “their passage has been willed above” (Inferno V.23). Dante and Virgil then come to a place of muted light - but not just muted, it is as if they are deprived of light - roaring with hurricane winds.

Often we find the punishment is described before the error is known, as though the reality of that sin is being expressed by the shade, the inner working of the psyche that resulted in sin; this is the contrapasso, or “the law of the just counter-penalty in Hell.”1 It is as if we feel the nature of the sin before it is described by Virgil or a shade that has been subjected to it.

In the tossing and turning of the shades, Dante’s imagery conjures up uncontrolled windswept abandon:

And as, in the cold season, starlings wings

bear them along in broad and crowded ranks,

so does that blast bear on the guilty spirits

V.40-42

They come across a multitude of shades whose sins were those of the flesh, including Semiramus, Dido, Cleopatra, Helen, Achilles, Paris, and Tristan.

He pointed out

and named to me more than a thousand shades

departed from our life because of love

V.67-69

Dante was overcome with pity and desired to speak to two that he saw. They came to him,

Even as doves when summoned by desire,

borne forward by their will, move through the air

with wings uplifted, still, to their sweet nest,

those spirits left the ranks where Dido suffers,

approaching us through the malignant air;

so powerful had been my loving cry

V.82-88

The pathos of this scene makes it one of the most well known moments in The Divine Comedy. Dante is so moved by the couple that he asks for their story; they are the first true ‘sinners’ subject to punishment that he speaks to who are within the circles of Hell.

The two lovers are Francesca da Polenta and Paolo Malatesta; Francesca was married to Paolo’s brother Gianciotto, Lord of Rimini, who killed them both upon discovery of their affair. Singleton points out the framing of lines 100-108 as anaphoric in the repetition of Love…Love…Love in the three stanzas. The first two stanzas point to two laws of love, the third, to it’s consequence. So, “Love, that can quickly seize the gentle heart” (100) and “Love, that releases no beloved from loving” (104), and the consequence was their “one death” (106). To point to these as laws almost takes the blame from the lovers, as if love acted upon them and they had no choice but to obey. Here, perhaps, is one reason that this story resonates so deeply; if they could not help but be swayed by a love that overtook them, is it just that they are punished? Their passion was so great that it followed them, unchanged in form, into Hell. Francesca tells Dante:

Love, that releases no beloved from loving,

took hold of me so strongly through his beauty

that, as you see, it has not left me yet.

V.103-105

Dante feels their passion, that the strength of it should outweigh anything that they did wrong, and in his compassion for them, thinks:

Alas,

How many gentle thoughts, how deep a longing,

Had led them to the agonizing pass.

V.112-114

He asked them how it had all come to be, and Francesca tells him the story that she and Paolo were reading the story of Lancelot and Guinevere from the King Arthur legends, and as they met time and again to read together, they fell to that same adulterous fate as the Queen and the Knight in their book. Paolo wept as Francesca tells the tale; he who “never shall be parted” from her (Inferno V.135).

So moved is Dante by their love that he faints dead away.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

We acknowledge our faults so that our sincerity may repair the damage they do us in other people’s eyes.

~ La Rochefoucauld

Throughout their lives, the damned souls we are about to encounter had countless opportunities to confess and repent, to change their ways, yet they chose not to. When they stand in front of King Minos, the formidable judge of the underworld, the first thing they do when they appear before him, they confess it all.

Minos’s judgement looks mechanical, almost tediously bureaucratic, he casts his judgement not by using his head but by wrapping his tail around himself. This is, as the great Dante commentator Singleton writes, where ‘the real Hell begins.’

Interestingly, those of you who speak Italian may have noticed that Dante describes Minos in the present tense, while most of this masterpiece is written in the past tense. This suggests that Minos’s judgment is not confined to the past—it continues even now, as you read these lines.

I. Judge not by consequence, but by truth.

Who is the main sinner in this canto?

Many would say, of course, it is Paolo and Francesca—and if so, you are correct. Yet, I believe another figure here reveals Dante’s sense of Divine justice even more profoundly. The character I hint at is Queen Dido.

Even as doves when summoned by desire,

borne forward by their will, move through the air

with wings uplifted, still, to their sweet nest,those spirits left the ranks where Dido suffers

approaching us through the malignant air;

The tale of Aeneas and Dido is one of the most unforgettable episodes in Virgil’s Aeneid. After fleeing the ruins of Troy during its sack by the Greeks, Aeneas embarks on a journey destined to lay the foundations of Rome. Yet, upon arriving in Carthage, he momentarily sets aside his destiny to indulge in a passionate affair with the city’s majestic queen. The story teaches us the importance of being responsible, even when there are more comfortable options on the table.

After indulging himself in vain deluding joys, Aeneas wakes up from his own spiritual slumber and continues his journey, leaving Queen Dido behind. When she discovers that the subject of her desire has left her, she takes her own life.

She takes her own life, yet we find her here, among the lustful. Why? Shouldn’t she reside in the seventh circle, with those who committed suicide?

That other spirit killed herself for love,

and she betrayed the ashes of Sychaeus;

Sychaeus was Dido’s first beloved husband who was murdered by her brother Pygmalion. Dido fled to North Africa and founded Carthage. Her uncontrollable desire for Aeneas and lack of memory of her husband was interpreted as a betrayal. But still, why is she here and not in the circle of those who ended their own lives?

This is where ‘the good of intellect,’ or reason, comes into play.

II. Subjecting reason to the rule of lust.

Hollander’s translation of these verses is slightly more precise in this case than Mandelbaum’s:

I understood that to such torment

the carnal sinners are condemned,

they who make reason subject to desire.

While King Minos’s judgment may seem mechanical and bureaucratic, Divine justice is far more profound and transcendent. The sinners in Inferno as well as in Purgatorio are punished by the sin that made them lose their ‘reason.’ In the case of Dido, she suffers because of her lust, lust that leads her to commit the tragic action - she made her reason subject to desire. Her sin was not the despair that drove her to take her own life, but the surrender of reason to uncontrollable desire. This is why we find her in the circle of lust and not in the circle of the violent.

‘The gate is wide’ says Minos to our companions. The sin that causes you to lose your reason gives rise to another, and Divine justice holds you accountable for the original transgression that led you astray.

III. Semiramis: Normalising Vice.

It is far easier to normalise a vice than to cure it. This is what the legendary queen of the Assyrian Empire did: she engaged in an affair with her own son and, to conceal it, abolished the laws against incest.

The French moralist François de La Rochefoucauld in his famous Maximes has a quote:

We often flatter ourselves that we have overcome our vices, when in truth, we have merely grown accustomed to them.

IV. Paolo and Francesca: The Dangers of Reading

When Francesca begins telling her story, her first three terzas begin with the word Amor (Love) (lines 100-108). Love, Love, Love. She worships Cupid and throughout her speech casts her blame on everyone but herself: on Paolo, on Cupid, on the Book.

Love, that can quickly seize the gentle heart,

took hold of him because of the fair body

taken from me—how that was done still wounds me.Love, that releases no beloved from loving,

took hold of me so strongly through his beauty

that, as you see, it has not left me yet.Love led the two of us unto one death.

Caina waits for him who took our life.”

These words were borne across from them to us.

This is the most well-known scene in Dante’s Commedia and there is no shortage of interpretations of it. My current copy of the Divine Comedy has on its margins my first notes and interpretations, when I read this canto for the first time.

I wrote about the atmosphere. Back then, when I read the Divine Comedy for the first time, I did not know anything about Boethius and his influence on Dante. But now I can see the connection, the exact idea that Dante has borrowed from his ‘teacher’.

Boethius begins his Consolation by describing his mind as besieged by evil Furies—figures that, in the modern world, manifest as “entertainment,” “distractions,” and “poisonous pleasures.”

Paolo and Francesca are immersed in a romance book that sets the stage in their minds, guiding them toward surrendering their reason to desire.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Themes 🖼️ :

Confessions

This is where the true hell begins. Here, sinners approach Dante and recount their stories. When they were alive, they had the opportunity to confess their sins—a confession that implies a willingness to change—but they chose not to. As you journey through the Inferno, pay close attention to the nature of these confessions. In Purgatorio, we will encounter sinners as well, but their confessions will be markedly different, imbued with regret and a genuine desire for transformation.

Isn’t this a brilliant metaphor for our own lives? We remain trapped in a personal hell within our minds until we are ready to confront and confess our weaknesses, allowing us to cast them off and renew our existence.

The present tense

Dante’s use of the present tense when encountering Minos delivers a striking message. It draws us into the immediacy of the scene, making us feel as though we are right there with him in the Inferno. As you read this post, Minos is actively judging souls and casting them into their circles, a vivid reminder of the eternal nature of the punishments unfolding before our eyes.

Minos’s Tail

As Barbara Reynolds and Robert Hollander highlight in their separate brilliant commentaries on this canto: King Minos’s judgement is mechanical, bureaucratic, everything is already decided by the Divine justice. He does not use his head, he uses his tail.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

And she to me: “There is no greater sorrow

than thinking back upon a happy time

in misery—and this your teacher knows.

Terms 💡 :

- Anaphoric - The repetition of a key word or phrase in poetic stanzas.

Characters:

- Achilles - Greek hero of the Trojan War (“Sing, goddess, the anger of Peleus’ son Achilleus”2) in Homer’s Iliad, his death is told of in other texts (by Cretensis and Phrygius) at the hand of Paris, who tricked Achilles with the promise of meeting his sister, Polyxena, instead meeting Paris, who slew him. The famous Achilles heel stems from the myth in which Thetis, his mother, held him by the heel as she dipped him into the river Styx to gain immortality; the place that she held him became his only spot of vulnerability.

- Cleopatra - Queen of Egypt, she was mistress to both Julius Caesar and to Mark Anthony. She committed suicide in 30 BC

- Dido - Founder and Queen of Carthage in North Africa, with historic tracings of her role as sister of Pygmalion, King of Tyre in the 7th century BC. Pygmalion had her husband Sychaeus slain in an intrigue, causing Dido to flee and found her own city. In Virgil’s Aeneid, the love story of Dido and Aeneas is legendary in its tragic nature, when Dido falls in love with Aeneas despite her vow to Sychaeus to remain faithful to him. Dido, upon being abandoned by Aeneas, kills herself on a funeral pyre which Aeneas sees in the distance as he is leaving Carthage. Virgil’s story of her can be read in Book IV of the Aeneid.

- Francesca da Polenta and - Paolo Malatesta: The two lovers whose story Dante hears in Canto V. One version of their story is told fully in Boccaccio’s Comento on the Divine Comedy. The detail of their acquaintance in his account show that their love began before her marriage to Paolo’s brother Gianciotto of Rimini, when Paolo was sent to stand in for his brother in their engagement so that she would not be repulsed by the ugliness of Gianciotto and refuse the marriage. Upon discovery of their affair, they were both killed by Gianciotto.

- Helen - Helen, Queen of Sparta was “the face that launched a thousand ships,” so well was she known for her beauty. She was abducted by Paris, son of the Trojan King Priam, to Troy, upon which her husband Menelaus enlisted the help of his brother Agamemnon and other Greeks, and they launched the Trojan war in order to recover her. The story is told in Homer’s Iliad.

- Minos - King of Crete in Greek myth, he was the son of Zeus and Europa. He is best known for the stories of his wife, Pasiphaë, and her unnatural desire for the bull of Poseidon, leading to the birth of the Minotaur, half man and half bull, who lived in the Labyrinth built by Daedalus. Plato attributes that Minos met with Zeus once every nine years to consult on the laws of his kingdom.3 Virgil placed Minos as judge in his Underworld as well,4 though Dante transforms him into a demonic, monstrous figure.

- Paris - Son of Priam, King of Troy, and Hecuba in the Iliad, Paris’ abduction of Helen of Sparta sets off the Trojan War. Paris had played the role of judge in a contest to determine which goddess was the most beautiful, Hera, Athena, or Aphrodite. When Aphrodite promised him Helen as a prize should he choose her as most beautiful, Paris awarded her the winner.

- Semiramus - A queen of Assyria in antiquity who ascended the throne after the death of her husband, Ninus, she was notorious for her licentiousness and for murder. Dante’s source, Paulus Orosius, wrote of Semiramus that she was “burning with lust and thirsty for blood.”5 She was also guilty of incestuous relations with her son, and with adapting the law to support her crimes.

- Tristan - Tristan and Isolde, from the Arthurian romances, fell in love when they mistakenly shared a love potion made for Isolde and her betrothed, King Mark of Cornwall, who was Tristan’s uncle. Their love affair lasted through a multitude of hardships, suffering, and intrigue, and was famous as a romance in the medieval era.

A Question❓

Love. Cupid. Amor. What about misguided love? Francesca’s story leaves Dante without his senses. Overwhelmed by the sense of compassion to the misguided lovers Dante loses his consciousness once more. What do you think about the nature of lust?

Mandelbaum, Inferno V.n31

Homer, Iliad I.1, translated by Richard Lattimore

Plato, Laws 624b

Virgil, Aeneid VI.432

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on Dante’s Inferno 78

There is such a fine line between lust and initial feelings of love for a person to whom you are attracted. So much of our attraction appears to be subconscious, and what begins as lust can become mature love over time if we work at it.

While I agree it is never right to have an affair, it's interesting that we seem to put that behavior at the top of our hierarchy of sins in marriage/partnerships. There are so many ways to mistreat and abuse your partner. Having a Catholic and Protestant background, I find it interesting that sex is frequently the emphasis (even today with some Americans blaming LGBTQ people for bringing down the rest of the country and calling them dangerous). In my mind, the best application of this canto to our lives today is to ask ourselves what overwhelming desires we have that are hurting ourselves, our partners and the people around us.

The character Dante's compassion is lovely to see. Apparently Dante, himself, may felt conflicted about how our hearts can be so taken with another person. How tragic that there is no hope (line 44) for these people who, supposedly, loved wrongly. Irrationality in love is the human condition, and analysing our feelings when we are newly in love surely decreases the joy we feel.

I am also reading The Complete Danteworlds by Guy Raffa. He makes an interesting application to today: What is our responsibility regarding the depiction of sex, violence, and love in the media we create or consume?

Three observations, and then a comment about what I believe is one of the most intensely personal cantos for our poet.

First: Minos is fascinating — he’s not a sinner, but rather an administrator and servant of divine justice — part of the bureaucratic apparatus of Hell, endlessly enforcing its order. “Next. Next. Next.” (I wonder if he’s questioning “lifetime appointments” for judges. One could also be inclined to ask if there is a PreCheck line for lawyers…😚)

Second: The inaugural mention of “pity” occurs here. One of the most fascinating progressions in the Commedia is the treatment of pity, compassion, mercy and justice as Dante “matures.” He has to learn to reconcile human emotion to the divine will — thus his encounter with Francesca reminds me of the adage “First the test, then the lesson.” His resolve is stress-tested by a beguiling enchantress, and it is a withering experience. The pilgrim swoons; the poet leaves it to us to discern the appropriate response to her “affliction,” which Isaiah 30:15 captures: “This is what the Sovereign Lord, the Holy One of Israel, says: “In repentance and rest is your salvation, in quietness and trust is your strength, but you would have none of it.”

Third: It’s interesting to see his treatment of courtly love evolve from the traditional form and the conventions he used in his earlier works. Now he begins to shed or transform its rules, and their focus on personal desire, to fit a broader spiritual and theological framework.

And now my TLDR comment: I grant you pride of place for Dido, but to me this is an intense and personally revealing canto for Dante. First, he is embarking on the painful process of relearning how to love, including deconstructing his poetic commitment to courtly love. Second, it’s his first encounter with a sinner (a charming immoralist no less), and he is almost completely unarmored for “battle” (Remember Canto 2, line 3-4?). Canto V screams “Thicken your armor and harden your heart!” A suit of unassailable armor is being built for and by him — *if* he completes his journey.

There’s a tale from Roman military yore (retold in the modern military) that’s an analogous to his experience here: When centurions conducted their inspections of legionaries, it was the custom that each soldier, on the approach of the centurion, would strike the armor breastplate that covered his heart with his right fist — where it had to be strongest to protect the heart — and shout “Integritas!” (Indicating not only wholeness and completeness of his armor, but also of his commitment to protect the Empire). That declaration was changed a century later to “Integer!” (undiminished – complete – perfect, indicating not only that the armor was sound, but that the soldier was sound of character.) The legionaire’s heart had to be as sound and rightly-ordered as his armor. The word integrity derives from “Integer;” in this canto, integrity means living in harmony with the meting out of divine justice — even for those “lightly carried by the wind.” At the end of his journey, that integrity will be rewarded with divine love and eternal happiness. Dante (barely) passes this test, but it has thickened his armor and hardened his heart. He is learning the lesson of Proverbs 11:3: “The integrity of the upright guides them, but the unfaithful are destroyed by their duplicity.”