The Importance of Rest or How Darkness Implicates Our Will

(Purgatorio, Canto VII): Valley of Princes, last stage of Ante-Purgatory and political strife

The word stress comes from tension—and tension often arises when we’re making progress. The purpose of rest, then, is not to escape that tension, but to release it—so that we can gather strength and continue the journey.

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Seventh Canto of the Purgatorio, we visit the Valley of Princes. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

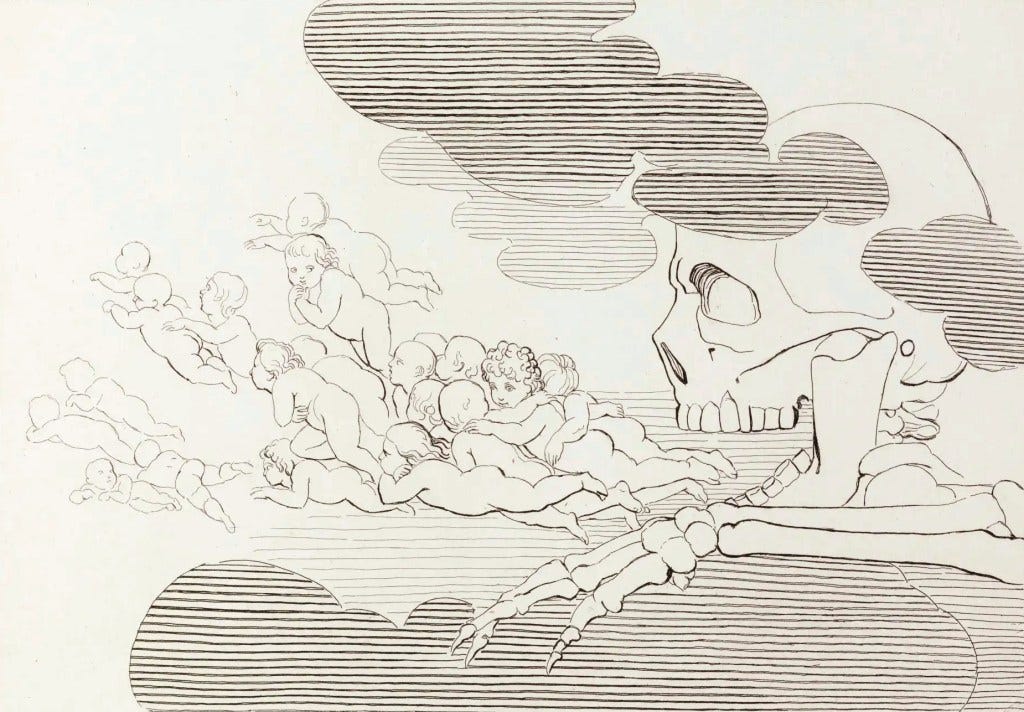

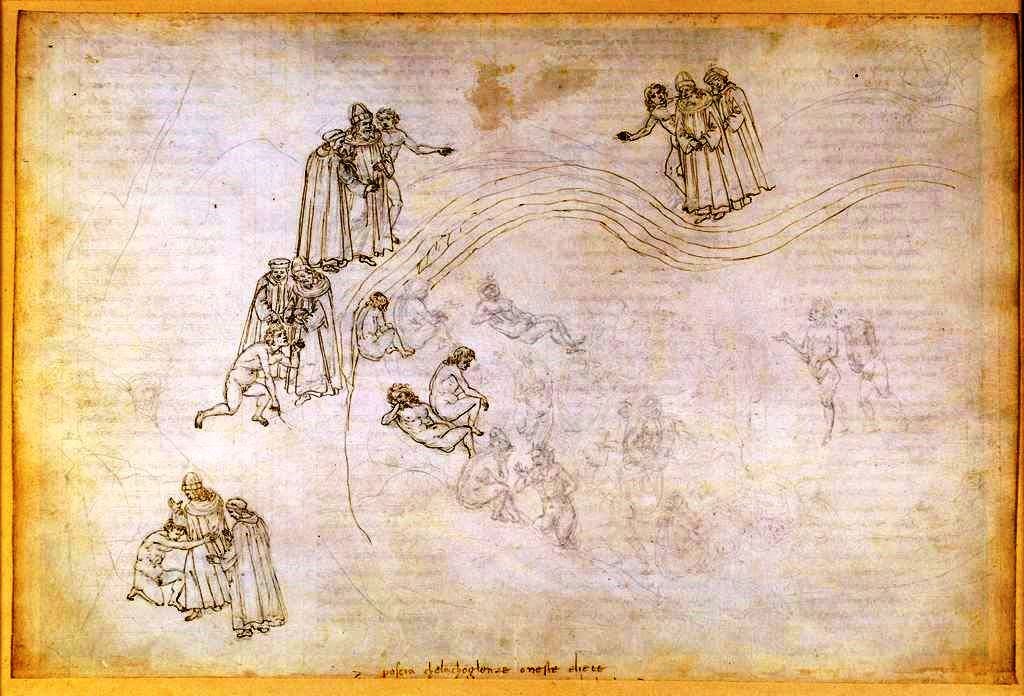

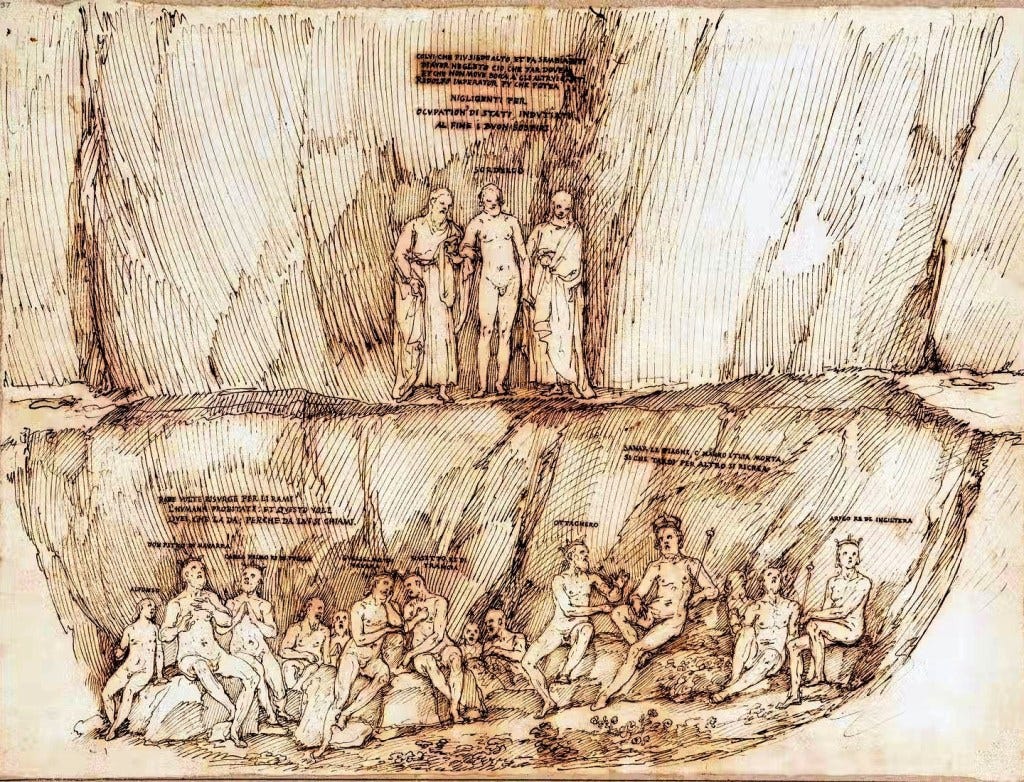

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Sordello and Virgil embrace - Sordello’s amazement at discovering Virgil’s identity - The rule of the Mountain whereby they may not travel at night - The Valley of the Princes.

Canto VII Summary:

After Dante’s digression on the state of politics in Italy at the end of canto vi, the story resumes where it left off at vi.75, with the embrace of Virgil and his fellow Mantuan, the poet Sordello.

They embraced repeatedly before Sordello asked again who they were, unaware still that he is embracing Virgil himself, and that Dante, standing nearby in the shade, is a living soul. Virgil introduces himself directly for the first and only time in the entire Commedia:1

“Before the spirits worthy of ascent

to God had been directed to this mountain,

my bones were buried by Octavian.

I am Virgil, and I am deprived of Heaven

for no fault other than my lack of faith.”

This was the answer given by my guide

vii.4-9

Virgil is referring to the time before Christ, in which he lived under Augustus Caesar - Octavian - and therefore the fact that, while virtuous, he did not have the opportunity for that redemption.

We can recall Virgil’s explanation of the virtuous souls in Limbo, in revisiting Inferno canto iv:

“They did not sin; and yet, though they have merits,

that’s not enough, because they lacked baptism,

the portal of the faith that you embrace.

And if they lived before Christianity,

they did not worship God in fitting ways;

and of such spirits I myself am one.

For these defects and no other evil

we now are lost and punished just with this:

We have no hope and yet we live in longing.”

Inferno iv. 34-42

This introduction is enough to fill Sordello with not only amazement, but deep reverence at meeting the most distinguished poet of the ages; as he went to embrace Virgil yet again, this time he did so as a servant would embrace his lord. Scholars have argued over what kind of embrace this would be; some say Sordello clasps Virgil’s feet or knees, others say he embraces him while bowing low; in any case, he showed his reverence due to the esteemed poet.

Sordello’s praise of Virgil emphasizes just how honored Virgil was, not just to Dante, but culturally and intellectually across the ages:

“O glory of the Latins, you

through whom our tongue revealed its power, you,

eternal honor of my native city,

what merit or what grace shows you to me?

If I deserve to hear your word, then answer:

tell me if you’re from Hell and from what cloister.”

vii.16-21

Virgil’s response made no mention of Dante; he described his state in Limbo in more detail, distinguishing the virtues that he held which were still not enough to move him beyond Limbo and into Purgatory, where opportunity for true movement is granted:

There I am with those souls who were not clothed

in the three holy virtues - but who knew

and followed after all the other virtues.

vi.34-36

The three theological virtues - faith, hope, and charity - are infused virtues given only with sanctifying grace. It did not in general lie within the power of pagans to “clothe” themselves in such grace and virtues, for such a possibility was established by Christ’s coming and His death for mankind upon the Cross…the “other”virtues are in general all the moral and intellectual virtues known to the pagans, but especially the four cardinal virtues - prudence, temperance, justice, and fortitude. Virgil draws no fine line here between these four as the acquired virtues, as distinguished from the four infused cardinal virtues.2

After these explanations, Virgil asks Sordello to point out the quickest way to the gate of Purgatory proper, Dante still just a figure in the background through their discussion.

Sordello offers to be their guide as far as he is able to go - notice that we are not told exactly what position he holds in Ante Purgatory; was he a Late repentant at the last moment, as the last group, or will he belong to the group we are about to encounter? He explains that the souls here do not have an exact fixed place within their given range, as did the shades in the Aeneid’s underworld:

Nobody here has a home you can point to. Our dwellings are dark groves,

River-banks serve as our bedding and meadows freshened by brooklets.

That’s where we live.

Aeneid vi.673-675

Sordello pointed out the late hour, and that as night falls, the souls in Purgatory are forbidden to ascend further, they must come to rest. He offered to show them a nearby group of souls and then to find a resting place for the night.

Virgil, who knew all the rules regulating movement in Hell, showed here that he was as yet ignorant of the rules of Purgatory. He questioned the mechanics of it; is it an external or an internal ceasing of movement? Sordello laid out the rule of the mountain:

And good Sordello, as his finger traced

along the ground, said: “Once the sun has set,

then - look - even this line cannot be crossed.

And not that anything except the dark

of night prevents your climbing up; it is

the night itself that implicates your will.

vii.52-57

Allegorically therefore, the meaning of the Rule of the Mountain, which prevents all ascent between sunset and sunrise, is that no progress can be made in the penitent life without the illumination of Divine Grace. When this is withheld, the soul can only mark time, if it does not lose ground, while waiting patiently for the renewal of the light. Nights in Purgatory thus correspond to those periods of spiritual darkness or “dryness” which so often perplex and distress the newly-converted.3

It seems however, that they are allowed to backtrack and move down the mountain, even in the dark; symbolizing the idea of the path of wisdom being obscured and in their movement without grace, they can only retreat. Of course no one would want to move down and stop their progress, however, so the best option is to stop and rest. This pause will be the first true rest of their entire journey up until this point.

Sordello led them to a ridge from which they will be able to observe the group that he mentioned before; they came to a valley below, the colors and scents of which were a feast to the senses, beyond any found on earth, and introduce the class of Late Repentants who were preoccupied, and due to external forces or luxuries neglected their spiritual duties.

Gold and fine silver, cochineal, white lead,

and Indian lychnite, highly polished, bright,

fresh emerald at the moment it is dampened,

if placed within that valley, all would be

defeated by the grass and flower’s colors

just as the lesser gives way to the greater.

And nature there not only was a painter,

but from the sweetness of a thousand odors,

she had derived an unknown, mingled scent.

vii.73-81

Those seated in this enchanting vision were singing the compline hymn to Mary, the Salve Regina, - Hail, O Queen - the final prayer in the liturgical day, which is said in the evening.

Hail, Holy Queen, Mother of Mercy; our life, our sweetness, and our hope. To thee we cry, poor banished children of Eve. To thee we send up our sighs, mourning and weeping in this valley of tears. Turn then, most gracious Advocate, thine eyes of mercy upon us and after this our exile show unto us the blessed fruit of thy womb, Jesus. O clement, o loving, o sweet Virgin Mary.

Similarly, did Aeneas see the shades in the Elysian fields chanting, although their song was less a mournful one and more filled with joy:

Look, he sees others spread out to the left and the right in a meadow,

Feasting, and singing a paean of joy as they dance through the fragrant

Clusters of laurels in groves from whose springs the Eridanus surges

Up to the surface and rolls in its ample flow through the forest.

Aeneid vi.656-659

Sordello tells them that it is easier to see the souls in the meadow from their vantage point above the valley, and proceeds to point out nine rulers, ranging from Emperors down to kings and princes, all of whom were distracted by affairs of state of with their wealth and paid too little attention to their spiritual path.

We should notice how beautifully the poet portrays Sordello’s bringing the poet to visit these illustrious men; he did so because he was a courtier and a diligent observer and admirer of the great men of his times, and he knew and related all about the virtues and conduct of his contemporaries.4

First is Emperor Rudolph, sitting higher than the others and uninvolved, not even joining in the compline hymn, one who neglected the affairs of Italy, helping to bring about it’s downfall, making it necessary that “another, later, must restore her” (96), which could refer to Henry VII of Luxembourg.

Seated next to him, comforting him is Ottokar, King of Bohemia and the lands of the Moldau and Elbe rivers, who was more respected than his son and successor Wenceslaus, fallen into lechery and devoid of valor; while in life Ottokar was an enemy of Rudolph, in Purgatory they have become unified and allied.

Ottokar II was king of Bohemia from 1253-1278. He refused to recognize Rudolf I as emperor, and the latter in consequence made war on him and defeated him at Marchfeld near Vienna, Ottokar being slain in the battle.5

Philip the Bold - Philip III of France - is in conference with Henry of Navarre - also called Henry the Fat - they are lamenting over the vices of Philip the Fair - the pest of France -, the son of Philip the Bold and son in law of Henry of Navarre. Dante saw Philip the Bold’s disgrace of the lily of France - the fleur de lis - in his retreat from battle with Peter III of Aragon, during which retreat he died of fever.

That same Peter III of Aragon - the robust one - sits nearby in Purgatorial unity and reconciliation with Charles of Anjou, he with a “nose so manly” (113-114).

[Charles of Anjou] was the most feared and redoubtable lord, the most valiant in arms, and the most lofty in arms of any king of the house of France, from Charlemagne down to him. And he was the one who most exalted the Church of Rome.6

The identity of the young man seated behind them has been disputed, he is referred to as a hopeful heir who might have brought a more orderly rule; he is commonly thought to be Alfonso III, the son of Peter III of Aragon. After his death, his brothers James and Frederick fought over the claim to the throne.

How seldom human worth ascends from branch

to branch, and this is willed by Him who grants

that gift, that one may pray to him for it!

vii.121-123

Here he refers to Charles of Anjou and Peter of Aragon, who “share the disgrace of degenerate offspring” (foot Hollander 160), whose virtue does not descend from the branch of the father to that of the son. He continues the analogy with reference to their wives to drive home the point:

The plant (Charles II) is as inferior to the seed (Charles I) from which it sprang as Constance may boast her husband (Peter III) superior to the husband of Beatrix and Margaret (Charles I), as Apulia and Provence know only too well.7

As they get closer to the end of the regal inhabitants of the valley of Princes, Sordello points out Henry III of England sitting alone, outside of the group as England was outside of the Empire, and nearby, William the VII, Marquis of Montferrat. His son’s revenge for his ignoble death caused the mourning and weeping of the regions of Monferrato and Canavese.

In 1290 he marched against Alessandria to quell a rising which had been fostered by the people of Asti, but he was taken prisoner by the Alessandrians, and placed in an iron cage, in which he died in February of 1292, after having been exhibited like a wild beast for seventeen months.8

💭 Philosophical Exercises

“Take rest; a field that has rested gives a bountiful crop.”

~ Ovid

In his wonderful lectures on philosophy, which I highly recommend, Professor Arthur Holmes explains how Ancient Greek thought evolved from what was once considered ‘pre-theology’ and ‘pre-science’ into the foundations of what we now recognise as theology and science.

Instead of paraphrasing the words of this gifted teacher, allow me to quote him in full here:

These earlier literary figures recognize that there are ordered processes of nature, but there are also ordered processes of moral life—that you get your due reward or the fates get you. So you have the macrocosm (nature as a whole is ordered, law-governed), the microcosm (your moral life is ordered, law-governed), and in between those two you have the emerging idea of the city-state as a law-governed order of society.

There's a parallel between these three things: the orderliness of nature, the orderliness of the city-state, the orderliness of the moral life. They see analogies between the three all the time.

In other words, theology, science, and philosophy are not static, cold systems—they evolve. They grow as we uncover new frontiers of the natural world through science, and as our expanding sense of morality gives shape to theology.

Think of a masterpiece of art or literature. Take, for instance, my favourite examples: Hugo or Michelangelo. Their works move us so deeply because they reveal, or give form to, feelings that already dwell within us—feelings we may not have yet fully understood or even discovered. They unveil the order within our inner world.

(This is why art, theology, and science are so deeply intertwined and why every Renaissance genius was, in essence, a fusion of artist, theologian, and scientist.)

The idea of Cosmic Justice, which Holmes eloquently explores in his second lecture, holds that Ancient Greeks believed that just as there is order in the natural world, so too is there order in the moral universe. And, as we discover the order that governs the natural world, so we discover the order of the moral universe through theology and myths. To live a good life therefore is to live in harmony with the rules of the natural world but also with the laws of the moral universe. And this, precisely, is what our journey through Purgatorio is about: aligning ourselves with that deeper, moral order of nature.

I. Elysian fields

The concept of the Elysian Fields evolved much in the way Professor Holmes describes in his lecture. Originally reserved for mortals with divine lineage, it gradually expanded to include those favoured by the gods—the righteous and the heroic.

Though the etymology of the word Elysian remains debated, one compelling suggestion links it to meanings such as “imperishable” or “incorruptible”—a resonance that fits beautifully with Purgatorio, where the soul’s aim is precisely to be purified of corruption.

In this canto, Dante himself seems to step into the background, allowing Virgil, his pagan guide, to take the lead in conversation with Sordello. Virgil regards the Valley of the Princes as something akin to the classical Elysian Fields. While Dante (the writer) never mentions Elysium explicitly, his description of this serene valley—lush with flowers and filled with the harmonious singing of Salve Regina—clearly evokes its classical imagery.

Once again, as it is always with Dante, he never merely borrows from the ancients; he recontextualises. Here, the souls dwell not in eternal rest, but in a state of hopeful anticipation, awaiting divine grace to ascend the holy mountain.

II. Virtues

The fall of the pagan world and the rise of the Christian faith are often oversimplified, as if one simply erased the other, wiping out everything that came before. But if we get a closer look, through the eyes of a secular history, nothing could be further from truth and these kind of arguments are easy to dispel.

The ideas of Plato and of Aristotle, of Stoics and Skeptics, of Cicero and Seneca,9 and one can go on and on, stand at the foundation of the Christian faith. In Arthur Holmesian terms it was an evolution of thought, one after another, and I believe my reader is wondering why am focusing my overview of this canto in this particular way.

In the same way as our ancestors once came up with four cardinal virtues such as prudence, justice, temperance and fortitude so did our later ancestors unveiled three Christian virtues which are faith, hope and love (charity). One set of virtues did not replace the other, but complimented the other, since being temperate and prudent is as valuable to a Christian as it was to a pagan.

Understanding the difference between the two is essential for our journey through Purgatorio, for the classical cardinal virtues are cultivated through habitual action—by repeatedly practicing temperance, courage, prudence, and justice. In contrast, the three Christian theological virtues—faith, hope, and charity—are not acquired through habit, but are infused by divine grace.

I believe that in this canto, since we are getting very close to entering Purgatory itself, Dante shows us that we are crossing a new threshold. We are crossing into an area where classical and Christian virtues intermingle.

This is why Dante the pilgrim feels like a secondary character in this canto. He stands there and observes how Virgil looks at what seems to him a familiar Elysian field and yet sees how different it is from the pagan description.

III. Temporality of Politics

Perhaps what cannot go unspoken is this: in the Valley of the Princes, we encounter rulers who were once bitter enemies—men who brought war and suffering upon one another. And yet here, they rest together in peace, serene, united in song as they chant the Salve Regina.

I often pause while reading Dante and imagine that what he describes is not merely a brilliantly crafted poem, but a real place. I picture myself standing there, witnessing these once-hostile kings and leaders—those who had been at each other’s throats—now joined in harmony, singing divine melodies.

If this were truly so, how small, how fleeting, how heartbreakingly futile our political divisions would appear.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. The Harmony of the Night and Day

It is beautiful to witness harmony in this part of the journey. Day gives way to night, and a natural rhythm governs the passage of time. There is order here—gentle, serene, and purposeful.

How different this is from the Inferno, where there was no true day, only an unrelenting night—a darkness that could scarcely be called natural. There, the damned were punished without pause, without rest, without end.

II. The Importance of Rest

But see now how the day declines; by night

we cannot climb; and therefore it is best

to find some pleasant place where we can rest.(43-45)

When Virgil speaks with Sordello, he believes that they cannot continue their ascent after sundown, fearing they might encounter demons along the way. Yet in this part of Purgatorio, there are no demons.

From a Jungian perspective, this makes perfect sense—we have already confronted our demons in the Inferno. They have been exposed, named, and faced in the depths of the psyche.

Now, in this peaceful valley, rest becomes not just necessary but meaningful. It is a sacred pause, a moment of contemplation, of stillness, a chance to reflect on the path behind and gather strength for the climb ahead.

I wrote more about the importance of such rest in my piece on Aldous Huxley, which you can read here.

III. Not anything except the dark of night prevents you…

And not that anything except the dark

of night prevents your climbing up; it is

the night itself that implicates your will.(55-57)

There is of course another angle we can look at the changes of the night and day - that is the angle and that is that the Sun represents the rise of the Divine Grace. So one cannot progress through three Christian virtues cited above without the light shining from heaven.

Of course this raises a question: How does one get that light? Is it some privilege?

My answer would be that one gets the divine grace by crossing Inferno.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

By the time I reached this section, I realized I had copied down nearly all of my favorite passages from this canto. I was especially moved by the part where it is only the darkness of night that limits the will—a subtle but profound insight.

Still, I want to share the passage below, as it beautifully complements the final reflections in the Themes section.

“Through every circle of the sorry kingdom,”

he answered him, “I journeyed here; a power

from Heaven moved me, and with that, I come.

Jean & Robert Hollander, Purgatorio 154

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on Purgatory 141-142

Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory 122

Singleton, quoting the medieval commentator Benvenuto 124

Singleton 150

Singleton 153 quoting Villani

Sayers 124

Singleton 158

Just one example: there was a correspondence between St. Paul and Seneca, where they discussed moral matters. It was later shown that is was a forgery and yet the moral universe of Seneca strongly corresponds to that of St.Paul.