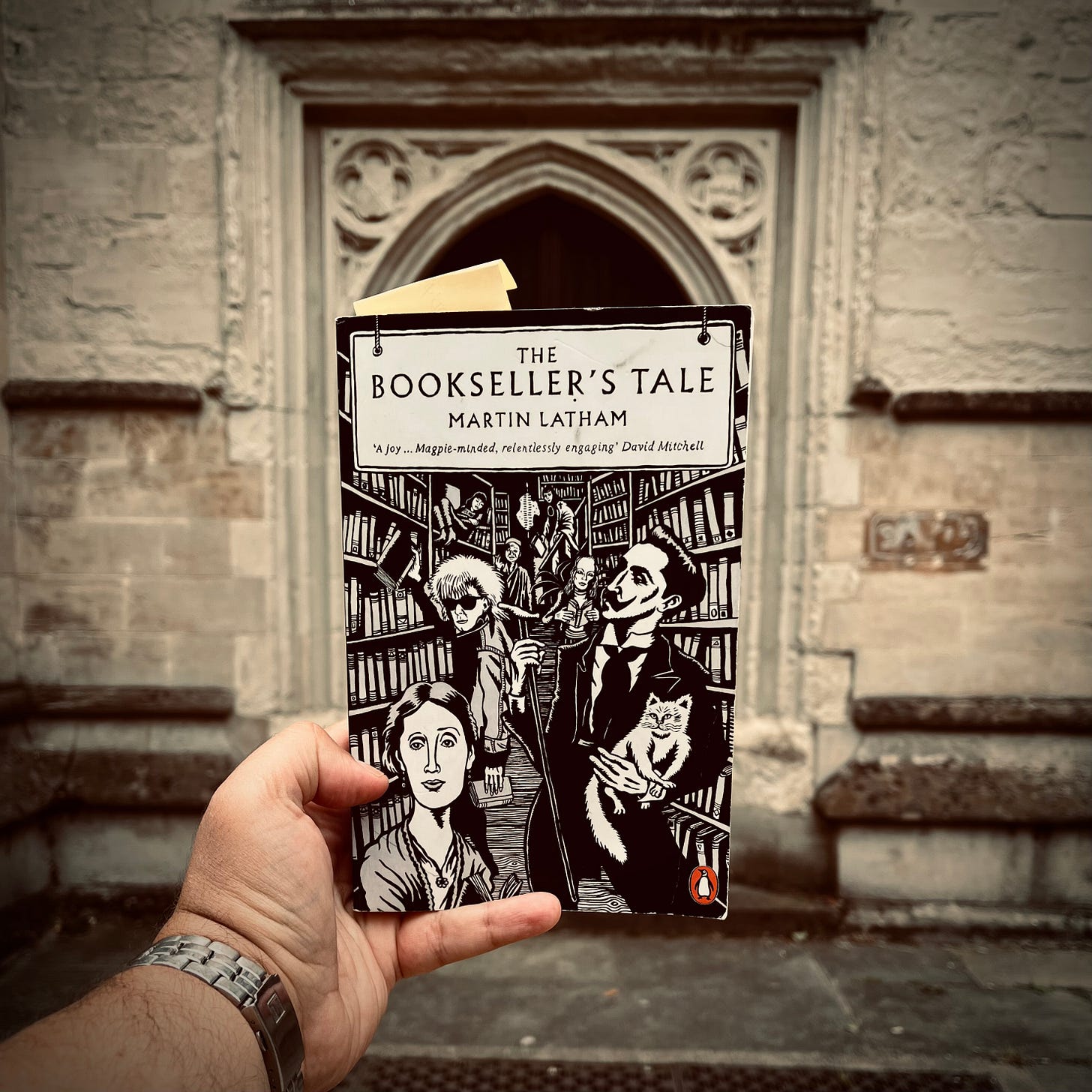

The Library of Babel (or, How Bats Rescue Books) 🦇 | Book Review

Review of Martin Latham's magpie-minded and engaging The Bookseller's Tale.

In 1730, the English Gothic novelist William Beckford visited the legendary Mafra Palace Library in Portugal. My reader might have seen this library on instagram reels and other lists of ‘the most beautiful places to visit’ or ‘the most beautiful libraries ever built’.

Beckford, however, thought Marfa Library to be 'clumsily designed with a gallery which projects into the room in a very awkward manner'1

He should have stayed quiet when it came to discussing architecture since he himself built an insanely tall tower on his house located near Bath, which collapsed three times within a few years of its construction.

If Beckford had stayed there overnight, the secret of the upper gallery would have become clear as hundreds of tiny bats swarmed from their roosting places behind the upper cases to eat insects which might threaten the books.

Small portals allowed them to fly around nearby orchards.

Interestingly enough, as Martin Latham points out in his brilliant The Bookseller’s Tale, booklice are not as evil as we tend to portray them. They only destroy books that are not being read. Thus pointing to us which ones we ignore for a long time.

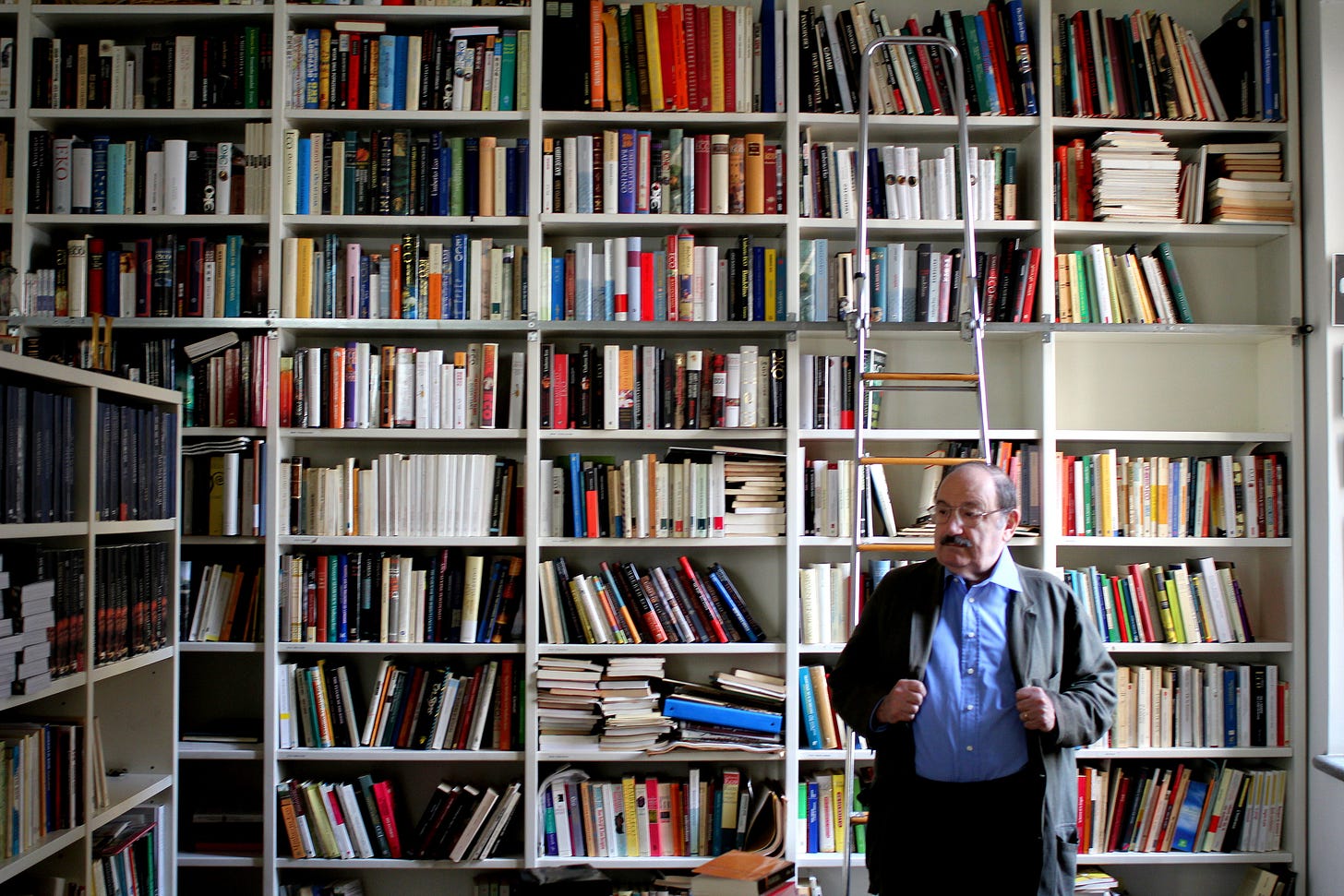

The stories from Martin Latham's personal journey as a bookseller are equally captivating to read. In the early 00’s, he contacted the publisher of Umberto Eco in the UK to invite him to an event in his store. The publisher responded that Eco never commits to such events. Latham didn’t give up and called Eco’s publisher in Milan and received a reply from the author himself.

Eco said that what he really wanted to do was to work in a bookshop, at least for a day. He did, and even sold one of his books to a customer, without revealing his identity.

When I read this story I got a strong wish to see the face of that customer when they finally found out that they bought the book from the great Umberto Eco himself!

However, the most thrilling tale from Latham's 35-year career as the manager of the Waterstones bookstore in Canterbury unfolded when he unearthed a Roman bathhouse floor beneath the philosophy section of his bookshop.

A large plinth near the Philosophy section indicated, the chief archaeologist told me, the presence of a devotional statue; my bookshop, too, had perhaps been a temple-library like a mini-Pergamum.

A perennial damp patch on the back staircase from the basement indicated the spring possibly a sacred one as at nearby Lullingstone, which may have attracted the Romans to the site.

Before we used to go to churches to find spiritual nourishment, but now that we've abandoned them, bookshops serve as our contemporary spiritual sanctuaries. We choose to go to bookshops when we need a space to escape, to spiritually regenerate, and to feel that life is bigger, greater and wider than our daily routine.

Bookshops possess a mystical power in themselves and that power is - serendipity.

Serendipity in the library or bookshop seems random and chaotic, but customers of my bookshop often speak about it as the natural way of browsing. Why?

It seems that browsing mindlessly is somehow browsing mindfully. Unmooring the calculating part of the mind in a many-chambered storehouse of books is quite natural to the many-chambered mind, with its subconscious and conscious, its stacks and upper floors, its attics, its treehouses and seldom visited bothies.

Library stacks mirror the undiscovered self.

Free-browsing, like free-diving and free-climbing, are activities unmediated by official interference; they are responses to an over-regulated and commercialised world. Browsing a library is to browsing online (jerked around by algorithms) what free climbing is to a coach tour.

This mystical power of serendipity cannot be replaced by algorithms, because algorithms base their recommendations on your previous choices. Algorithms live in the past, while bookshops and libraries direct you towards the future.

Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle states that you cannot know both the position and velocity of an object because everything is both particle and wave.

I now propose Latham's Uncertainty Principle, which states that, upon entering a bookshop, you cannot know both who you are and who you might become, because you are both memory and instinct.

My first favourite bookshop is located in the heart of Prague, on Wenceslas Square, and it’s called Palac Knih (Palace of Books). As a student, at the outset of my reading journey, I was unsure of my interests and which authors resonated with me the most. However, serendipity, guided by Latham's Uncertainty Principle, somehow led me to the right shelves. This bookshop was where my reading journey began.

Five hundred miles away from Prague is the beautiful Polish city of Krakow, where in the 1480s a young woman disguised herself as a man to get into the university. Her deception was successful throughout the course, getting excellent marks and being noted for her conscientiousness, but just before graduation, her deception was revealed.

She had to attend a tribunal and when the judge asked her to explain her motivation she simply replied: ‘Amore studii’ (for the love of learning)

This response moves me each time I read or remember it. I am happy to say that the judge let her off.

She chose to be sent to a convent - these were often secret refuges for frustrated female readers - where she quickly rose to be abbess and turned the whole place into a sort of academy for book-mad girls and women.

I feel incredibly privileged to have faced no censorship or financial obstacles in pursuing my passionate bibliomania. My own grandfather, who grew up in the Soviet Armenia, had to skip meals and wait for months to obtain a book he desired.

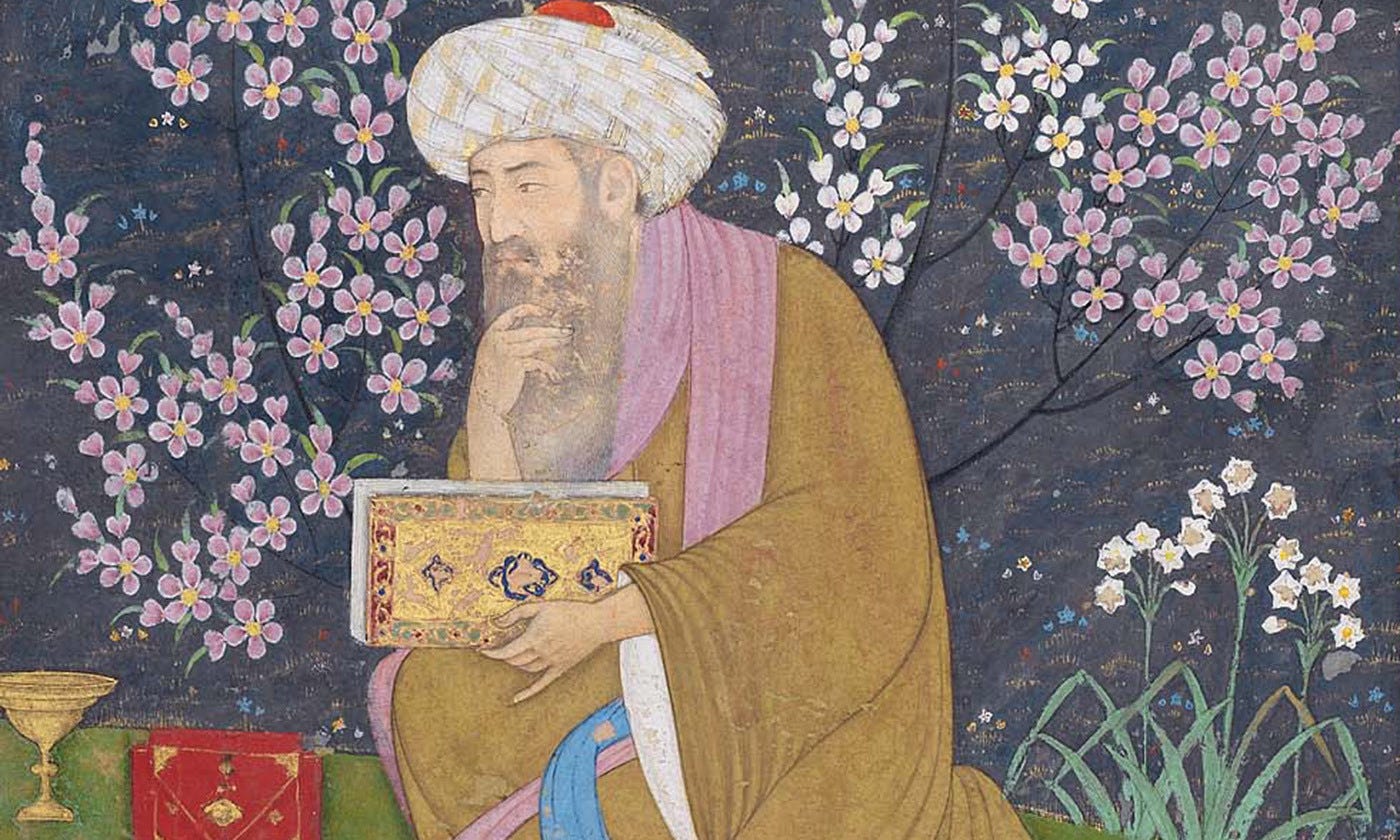

If he had been luckier and lived in another country (or century) he could have ended up like the great Persian scholar al-Sahib ibn Abbad, when the Emir of Persia offered him a job of running the empire’s most important province, Khosaran, Ibn Abbad declined:

… on the grounds that it would take 400 camels to move his personal library.

I wonder about the closeness of Ibn Abbad's relationship with his wife and what she made of his book obsession. Mainly because, four years ago, when I was moving houses, my wife was astounded to realise that we required an entire van (the equivalent of 8 camels) just to transport my books.

I must emphasise that book buying is never mere consumerism; on the contrary, bibliophiles acquire 'too many' books to construct a protective wall against life's trivialities, including consumerism.

My father was an extreme case as a collector, building, as my brother said, 'a fortress against the triviality of the outside world.’

This is the reason why almost every great library started first as a private collection. Libraries were rarely built by the governments, they were (and still are) often maintained and manipulated by governments, but almost never originate from them.

I used to walk past the British Library on my way to work every day for four years but never knew that the British Library should be called ‘The Robert Cotton Library’ instead. It was Robert Cotton’s collection that became:

…the foundation of the British Library, but only because Cotton campaigned via Parliament for the state to acquire his books, which greatly outnumbered the King's collection.

Far from being financially motivated, according to one historian Cotton 'virtually gave his books to the nation'.

Last year, I visited the University of Oxford, where I explored the Bodleian Library which was founded on the private collection by Queen Elizabeth’s diplomat Thomas Bodley.

The story is no different with The Library of Congress which was originally a small library for politicians, until Thomas Jefferson’s personal collection joined it and made it a national library for the people.

And so it goes, the National Library of Italy is based on the Medici family’s collection; The Bibiliothèque Nationale started as a private royal library; the Polish National Library is a creation of two book-mad brothers.2

The lesser-known Gladstone Library, where you can stay overnight (as I did), is based on the collection of the British Prime Minister William Gladstone who owned 35,000 books and is rumoured to have read 20,000.

Borges was right when he said that paradise must resemble a library. There is something mystical about books that only a true bibliomaniac can understand. We still don’t know what treasures are kept within the library of the Vatican, what knowledge do they contain that the Vatican tries to guard so much.

Isaac Newton, who wrote over a million words on alchemy, more than he did on science, would have provided a clear answer: books hold the knowledge that could bring us closer to understanding the mysteries of the universe.

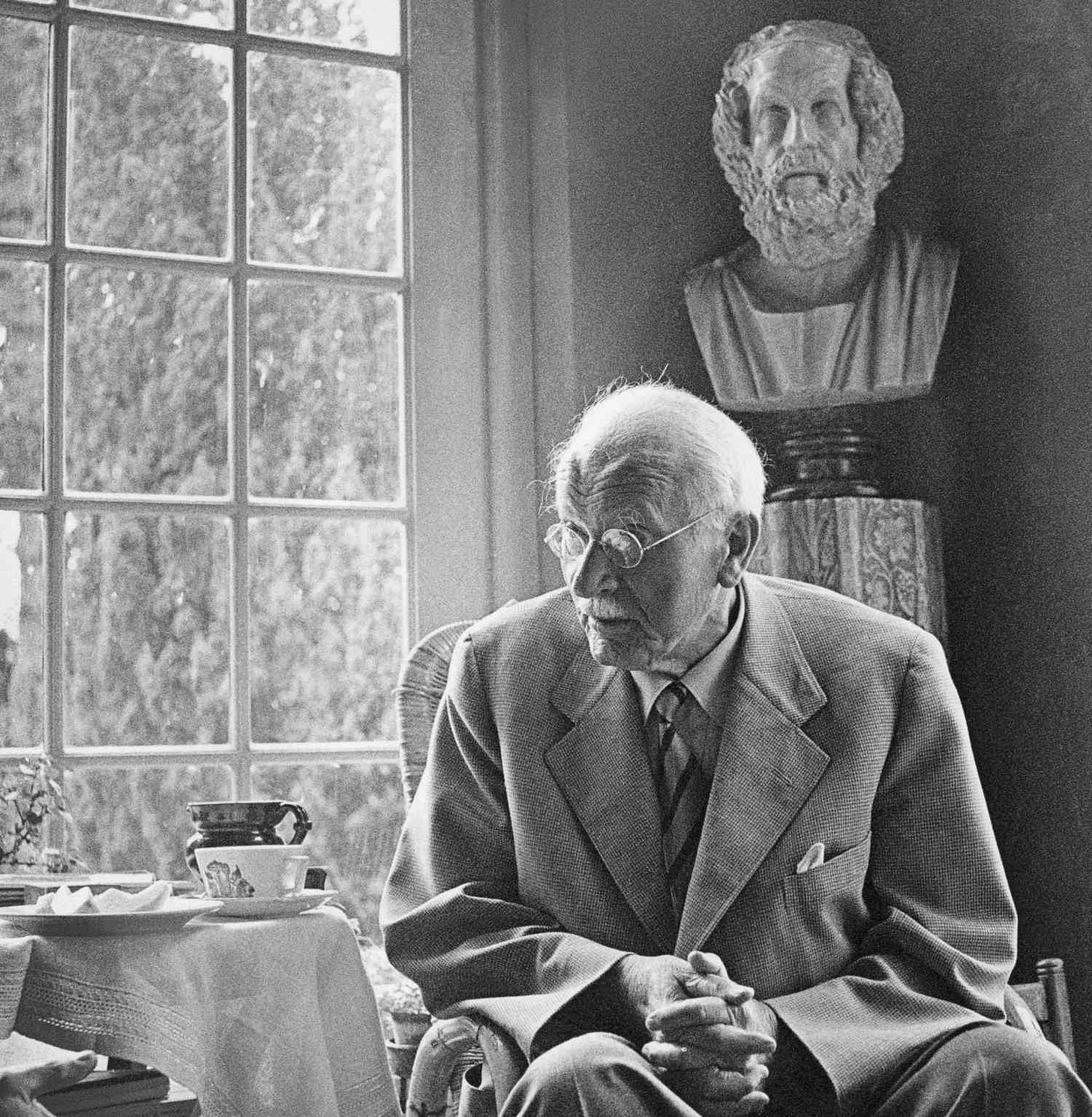

For the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung our personal libraries were connected tightly to our subconscious. There is an exceptionally vivid story illustrating this connection between the library and the subconscious, involving Jung's friend who had recently passed away, visiting him in a dream:

… the friend conducted him to a red book on the top shelf, with an indistinct title. The morning after the dream, Jung visited his friend's widow and, for the first time, entered his library.

There on the top shelf was a red book called The Legacy of the Dead. Jung found comfort in the title's apparent message that his friend's work would in some way be lasting.

People who blame religion for censorship often overlook secular organisations that also intentionally impede the spread of enlightenment. In the beginning of the 20th century, when public libraries were springing up across Britain, the powerful brewers’ lobby did everything in their power to stop the construction of local libraries.3

In Britain, where the establishment of a local library board required a taxpayer levy, the take-up rate was initially sluggish. Even when a library rate was proposed, hostile campaigning, often underwritten by the powerful brewers' lobby, could ensure that it was defeated.

~ The Library, Arthur der Weduwen

Those who empty their minds with alcohol cannot fill their minds with knowledge. Brewers know this. It’s silly to think that they stopped impeding enlightenment back in the early 20th century and do not continue to fight against reading today.

To illustrate what I mean, dear reader, please take a look at the park depicted in the photo above. This park is one of my favourite reading spots in England. When I'm there, I frequently encounter the gardener who arrives to plant new flowers, tend to the existing ones, and mow the grass.

I remind myself that the reason this park is such a pleasant and beautiful place to be is because of the care of this gardener.

In autumn, he prepares the flower beds for winter, and in winter, he treats them so they will bloom in spring.

The book universe urgently requires a gardener today. Our local libraries, independent bookshops, and our attention spans are enduring a harsh winter. Spring will arrive, but these treasures need nurturing now, and each of us book lovers must take on the role of a gardener, preparing for the impending second renaissance.

Martin Latham, The Bookseller’s Tale, pp.125-126

Martin Latham, The Bookseller’s Tale, pp 130-136

Arthur der Weduwen, The Library, p.11

I see you enjoyed it as I did. You did much more independent research than I did. I always learn something from you.

This might be my favorite of your always amazing updates.