A man’s character is his fate.

~ Heraclitus

In January 2025, I will turn 35—the very age at which Dante begins his journey through the Inferno, awakening in the shadowy depths of the dark forest. There is something almost mystical about reaching this age, all the great themes of our life converge together. At this stage our past meets our present; we begin to reflect on what we love and whom we hate; we wonder whether our purpose in life has a meaning; at this stage, we choose which parts of our character we should raise and which we should shed.

At this point, we find ourselves riding the crest of life’s wave. We have weathered the storms that brought us here, yet we cannot predict whether the winds and waves ahead will grow stronger or subside. This is when the nature of our character will define our fate. This is when the way we steer our ark will tell whether we will ascend to Heaven or descend to Hell.

The violent tempests can often prove useful to us. They awaken our consciousness up from the spiritual slumber. Without the storms, we might not even be aware that we are in a deep sleep. This is what Dante says himself right at the start of his poem:

I cannot clearly say how I had entered

the wood; I was so full of sleep just at

the point where I abandoned the true path.

Dante does not encounter this journey in a dream; he awakens to find himself already within it. The poem could not have been written had the state of confusion and despair in which the poet found himself at the outset not been confronted and triumphed over. The trajectory is both linear and circular: in our end is our beginning. The story of the journey is, among other things, the story of becoming capable of writing the poem about the journey.1

Reading Dante, in other words, is confronting one’s own weaknesses. It is attempting to change one’s character in order to alter the course of our fate. As Virgil, Dante’s guide through Hell and Purgatory, says in his Aeneid:

It is easy to go down into Hell; night and day, the gates of dark Death stand wide; but to climb back again, to retrace one's steps to the upper air - there's the rub, the task.2

Our troubled conscience often manifests itself as our personal hell. In our world in which ‘the popes fail in their role as spiritual guides’ and ‘the secular rulers are motivated by naked ambition and greed’3 Dante is indispensable. The beauty of The Divine Comedy is that it tells us how ‘to retrace one’s steps to the upper air’. Dante reminds us of our divine origins that we ‘were not made to live [our] lives as brutes, but to be followers of worth and knowledge.’4 We were born to look up at the stars, into the heights.

Botticelli, Petrarch, Leonardo, Michelangelo, Delacroix, Rodin, T.S. Eliot, Nabokov, Borges, and countless others who have looked to the stars found themselves profoundly moved by Dante’s masterpiece. James Joyce once wrote ‘I love my Dante as much as the Bible. He is my spiritual food, the rest is ballast’ and my favourite Jorge Luis Borges said in his lectures ‘the best book literature has achieved’.

Artists, painters, and authors were not the only ones inspired by Dante’s genius.

In 2019, I visited Gladstone’s library, one of the few libraries in the world where you can rent a room and spend a night. Needless to say, it was a bibliophile’s heaven! William Gladstone, a British Prime Minister, amassed an extraordinary collection of 30,000 books over his lifetime. Driven by his love of knowledge, he established a library to share his collection with the public, ensuring wider access to his treasured volumes.

About 1000 books from this collection were dedicated to Dante. I could not believe my eyes when I saw rows upon rows of books on The Divine Comedy. I would need a whole other life to read them and another to understand them fully.

If the human mind produced an extraordinary work of literature that could prove the existence of God, Dante’s The Divine Comedy is one among very few. I once spent a month reading about the significance of numbers in the poem. Number three, for example, plays a crucial role.

The poem is divided into three parts (Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso), each part consists of 33 Cantos 5, the poem is written in terza rima or third rhyme, there are nine circles of hell reflecting the multiplication of number three (3x3) and so on. The Divine Comedy is poetically harmonious and mathematically symmetrical. Or, perhaps, better to say musically symmetrical, his poem is like a Beethoven sonata.

In his essay ‘Dante, Einstein and Three Sphere’ the Italian theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli tells us that the description of the Three Sphere heaven that Dante describes in Paradise matches exactly with Einstein’s 1917 description of the Three-Sphere structure of our universe.

He is describing a ‘three-sphere’, the shape that in 1917 Albert Einstein hypothesised was the shape of our universe, and that today remains compatible with the most recent astronomical measurements.

Dante’s unbridled poetic imagination and extraordinary intelligence anticipated by centuries a brilliant intuition of Einstein’s on the shape that our universe might have.6

My jaw dropped when I first read this, how is this even possible? How could Dante know or imagine this with such precision 700 years before Einstein?

Interestingly enough the final 13 cantos of Paradiso, in which he describes Three-Sphere heaven, could not be found after Dante’s death. However, Dante’s son Jacopo saw a mysterious dream that pointed out to him that there was a secret hiding place behind the hanging in the wall where upon awakening he found the last pages of The Divine Comedy.

Dante was a soldier, a poet, a theologian, a scholar, and a scientist. The Divine Comedy is not just a masterpiece of human imagination. It is an encyclopaedia that unites everything together from mythical heroes to the scientific structure of our universe.

Dante seems to be an infinite well, the more you draw from him deeper he gets. Michelangelo and Leonardo used to debate the meaning of certain passages from The Divine Comedy, while Florentine citizens organised public readings of the poem, and the great Giovanni Bocaccio was chosen to guide Florentines through Dante’s masterpiece.

It seems I have chosen an incredibly daring task to begin my thirty-fifth year on this Earth to follow the footsteps that were treaded by much greater minds than myself. But even wrestling the great is acceptable if it is approached with humility.

The renowned painter Caravaggio, in his depiction of David slaying Goliath, inscribed the words “Humility kills pride” on David’s sword. Goliath, consumed by his pride, met his downfall, while David, fortified by his humility, emerged victorious.

At the very beginning of his poem, Dante himself hesitates to embark on the journey through Hell. He questions his guide, Virgil, about his worthiness, expressing feelings of weakness, fear, and self-doubt.

Virgil replies to his apprentice:

If I have understood what you have said,

your soul has been assailed by the cowardice,

which often weighs so heavily on a man -

distracting him from honourable trials.

Let us not be ‘assailed by the cowardice’ so we can pass courageously through ‘honourable trials’. Virgil continues on with his speech telling Dante that the path was ordained through him by Beatrice, Love, from Heaven.

‘What a scholar one might be if one knew well only some half a dozen books’ wrote the great Gustave Flaubert in one of his letters.

By the end of this journey, I aspire for Dante’s The Divine Comedy to become my Iliad, much like Alexander the Great’s cherished copy. Alexander, famously, kept Aristotle’s annotated Iliad under his pillow throughout his conquests, using it as inspiration to command the known world. Yet, while Alexander built an empire through war, we should aim to construct a different kind of kingdom—an empire of the mind, our inner citadels, with Dante’s The Divine Comedy as our guide.

Let us reshape our characters to transform our destinies. Let us escape Hell by daring to believe in Heaven. And let us guide one another as Virgil guided Dante.

As always, but especially now—confide tibimet (trust yourself).

Hello friends!

I hope you enjoyed this piece, but before I’ll let you allow me share with you a couple of reminders:

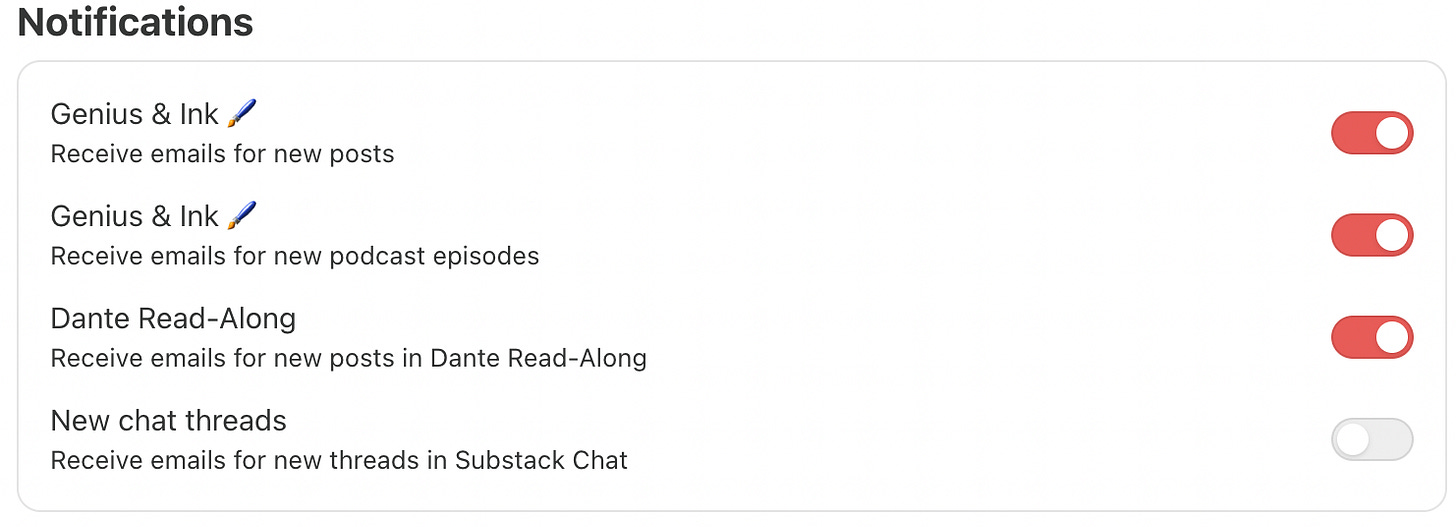

Dante Read-Along begins on January 12, this is when we are going to meet the great poet in Canto I. Please have a copy of The Divine Comedy by then.

I created a general chat on Substack where you can meet and greet other members of Dante Read-Along.

… and finally, if you DON’T want to receive my letters on Dante but would like to receive my regular essays make sure to tick the toggle for Genius & Ink but remove from Dante Read-Along

Proofread by

Dante Logo Design by

Prue Shaw, Reading Dante, p.6

Virgil, Aeneid, Book VI

Prue Shaw, Reading Dante, p.43

Dante, The Divine Comedy, Canto XXVI (Mandelbaum)

There are total 100 Cantos in the Divine Comedy. The first part begins with a Prologue Canto and then journey begins and lasts for 33 Cantos.

Carlo Rovelli, There are places in the world where rules are less important than kindness

What an utterly marvelous opening to this project—and the very happiest of birthdays to you, too. I also have a birthday in January, though at quite a different stage in life (I will be 76). That alone will make this project interesting for me (I have never read more than a few pages of Dante, even in all these years). I was fascinated to see the translation you chose for the first three lines here, quite beautiful. Am I right it is Kline’s (so google seems to tell me)? I also thought, if you haven’t seen it, you might enjoy Caroline Bergvall’s poem VIA, which is a compilation of several translations of those three lines: https://carolinebergvall.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/VIA.pdf May the journey be fulfilling, and thank you so much for being our guide.

Many happy returns for your birthday, and how fortunate for us to be invited as guests for your next orbit, as you guide us along Dante's path. My volume of his work has been on my bookshelf longer than you have been alive. It's been with me through so many iterations, locations, detours and relocations; titles, employments, losses, loves and joys - so, it's time. I'm looking forward to a lovely walk, one canto at at time. Thank You.