Vice & Virtue: The Art of Reflection

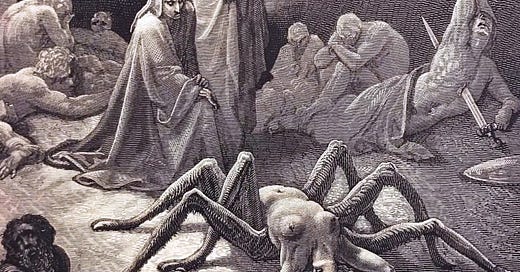

(Purgatorio, Canto XII): Dante cleanses Pride, Anti-Humility and Musica Diabolica

A man sets out to draw the world. As the years go by, he peoples a space with images of provinces, kingdoms, mountains, bays, ships, islands, fishes, rooms, instruments, stars, horses, and individuals. A short time before he dies, he discovers that the patient labyrinth of lines traces the lineaments of his own face.

~ Jorge Luis Borges

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

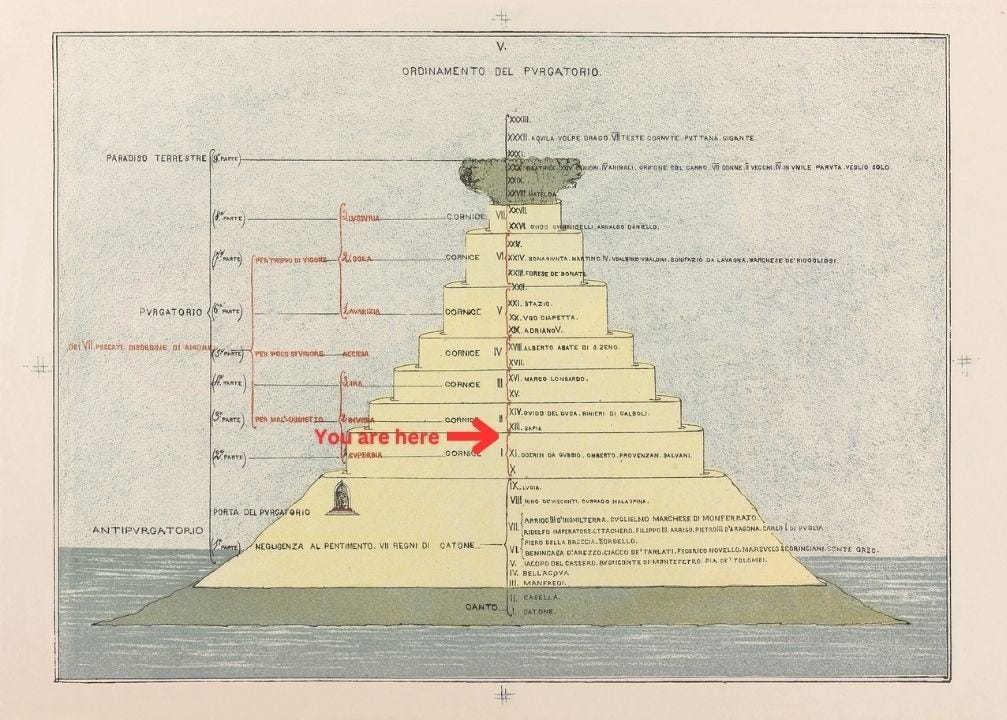

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Twelfth Canto of the Purgatorio, the first P is erased from Dante’s forehead. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Dante and Virgil leave behind the penitents of the Proud - Carvings in the rock on the ground - Examples of Pride - The Angel of Humility - The cleansing of the first P from Dante’s forehead - The path to the second terrace - The hymn of Beatitude.

Canto XII Summary:

Dante concluded his conversation with Oderisi, walking with slow, patient, humility like the humble ox, until Virgil encouraged him to continue on the path; only through one’s own effort could one move forward, and Oderisi had his path to fulfill, as Dante had his.

“Leave him behind, and go ahead;

for here it’s fitting that with wings and oars

each urge his boat along with all his force,”

I drew my body up again, erect-

the stance most suitable to man-and yet

the thoughts I thought were still submissive, bent.

xii.4-9

Those thoughts, those submissive, bowed thoughts of humility, were Dante’s moment of purgation of Pride, that swollen pride he had recently discovered within himself.1 His lightness of foot as he moved forward is testament to that transformation.

Virgil drew Dante’s attention to his feet to see carved effigies, like tombs set into the floor of medieval churches, the carvings representative of a life. Even the act of bowing to view them was part of the purification of pride into humility.

Here begins a brilliant exposition upon 13 examples of pride which are so layered in meaning and symbolism, ranging from the structure of the first word of each tercet to the parallels among the biblical and classical figures that they portray.

Dante begins with a unique poetic device called an anaphora, similar to an acronym in function, which extends from lines 25 to 63. This is just one of the layers of meaning. Dorothy Sayers, in her commentary, explained it most succinctly:

[The tercets] are divided into three groups of four examples, followed by a concluding example. Each example occupies one terzain; each terzain of the first group begins [in Italian] with the word Vedea = I saw; each terzain of the second group begins with the word: O; and each terzain of the third group begins with the word Mostrave = showed; while the three lines of the final terzain begin with Vedea, O, Mostrava respectively. Thus the initial letters of the three groups, as also of the concluding terzain, if read as an acrostic, display the word VOM or (since V and U in medieval script are the same letter) UOM, which is the Italian for MAN.2

While this descriptive lettering does not transliterate in English, the reader will see that in most translations, while not matching the Italian, it does keep in line with the function of the same words beginning each tercet.

Another way to read these thirteen examples is to see them as the opposite quality of those figures carved into the white marble that Dante and Virgil encountered when they arrived on the first terrace.

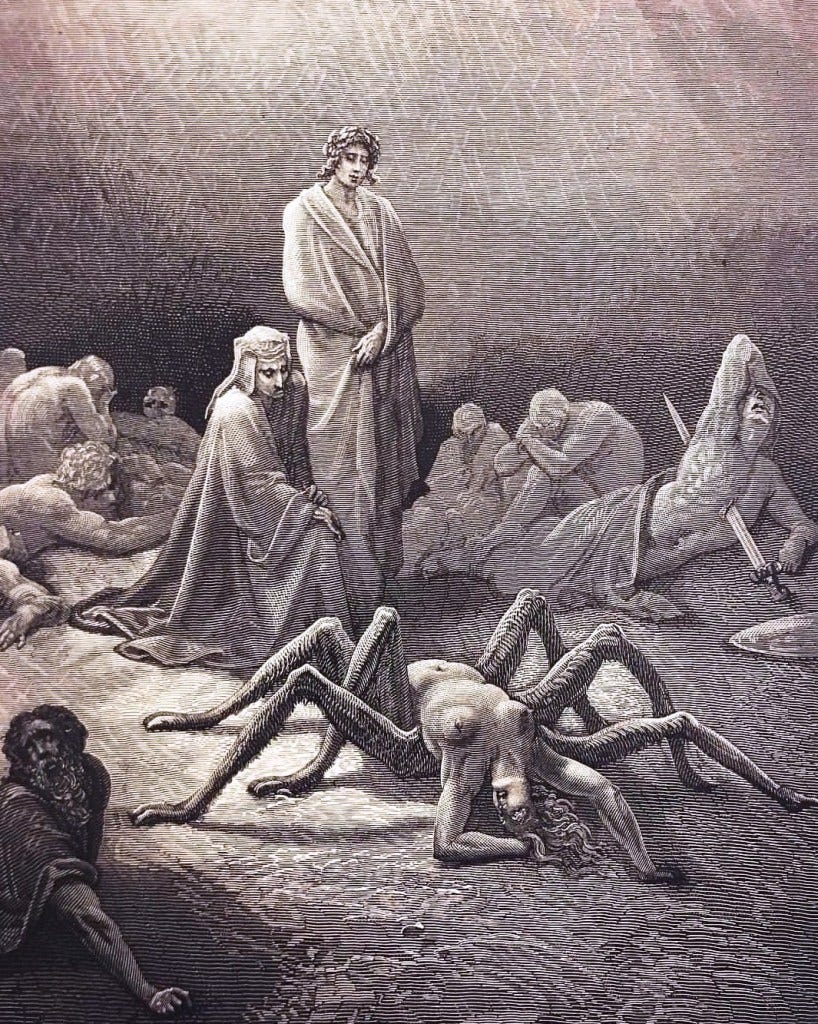

The first four tercets in this group in this reading are in contrast to the humility of Mary; Lucifer, Briareus, Apollo, and Nimrod, rather than bow in humility before God, challenged the power of God and strove to be equal in strength or place. The second four tercets contrast the humble praise of King David’s dance of joy; Niobe, Saul, Arachne, and Rehoboam all exhibited arrogance before God, or hubris. The third set of four tercets contrasted the humility of the Emperor Trajan before the widow with examples of those who had a defiant pride before men; Alcmeon, Sennacherib, Tomyris and Judith.

The thirteenth tercet then, blends all of these examples into the classical example of the greatest fall from pride, that of the city of Troy. We will explore these themes and characters in more detail below in the Philosophical exercises.

So moving were these carvings, so perfect, that they could only have been created by God, as were the white marble carvings of which their subjects are the opposite. Dante continued on with head bent in humility as he examined each one.

What master of the brush or of the stylus

had there portrayed such masses, such outlines

as would astonish all discerning minds?

The dead seemed dead and the alive, alive:

I saw, head bent, treading those effigies,

as well as those who’d seen those scenes directly.

Now, sons of Eve, persist in arrogance,

in haughty stance, do not let your eyes bend,

lest you be forced to see your evil path!

xii.64-72

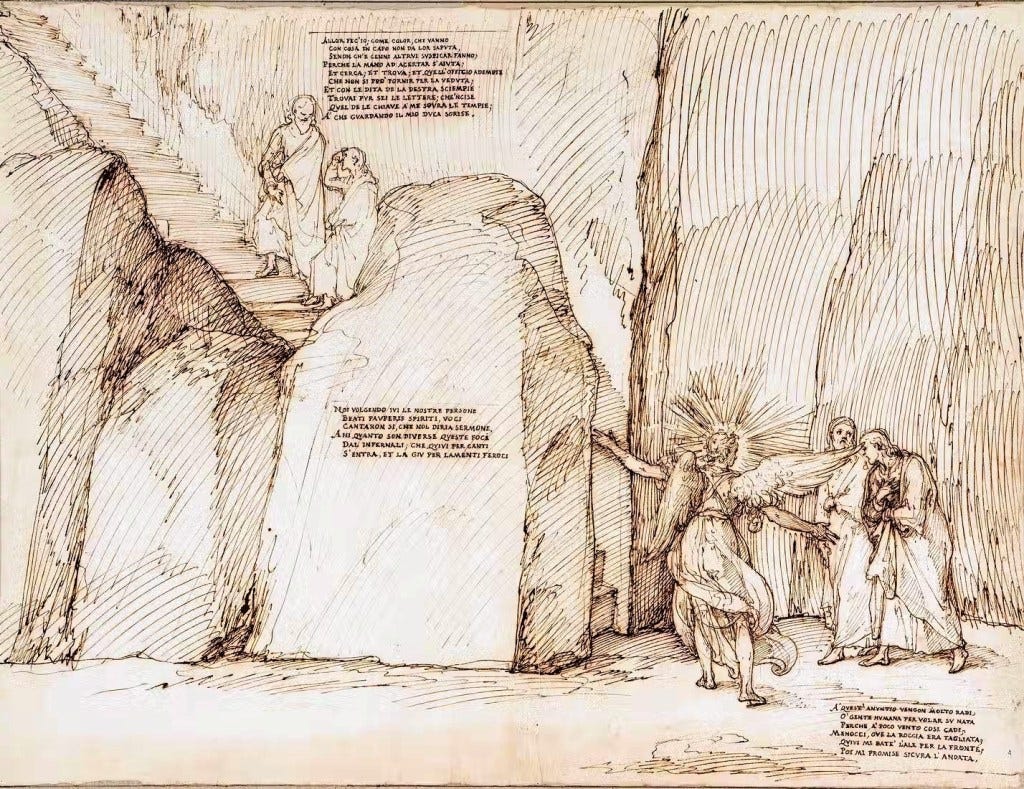

Dante used the imperative to call out to those proud souls, sons of Eve who were in contrast to those of Mary; pride versus humility. Virgil called for Dante to lift his head, to recognize his cleansing of the whip of Pride, and to hearken to the angel that was coming to meet them, the angel of Humility. In Dante’s state of moving toward purification, he was even able to look at this angel’s face:

See there an angel hurrying to meet us,

and also see the sixth of the handmaidens

returning from her service to the day.

Adorn your face and acts with reverence,

that he be pleased to send us higher. Remember-

today will never know another dawn.

xii.79-84

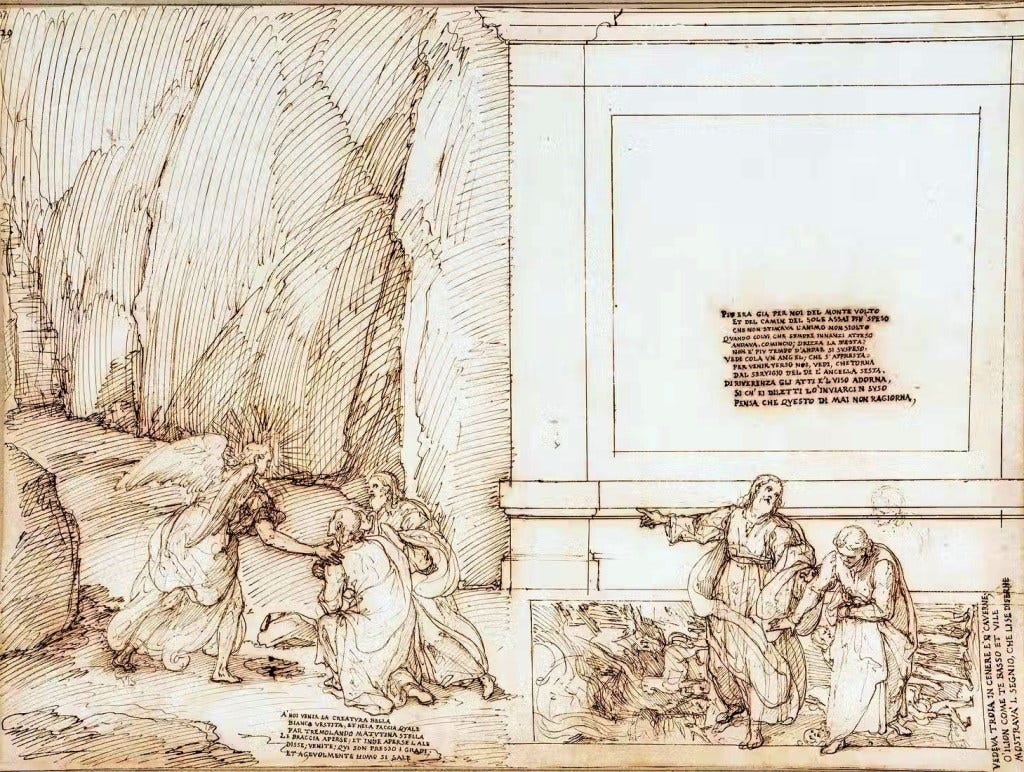

In a most beautiful scene, the angel called to Dante with outspread wings, assuring him that the climb will ease now that he has been purged of Pride. The angel wiped away the first P from his forehead with a movement of his wing.

This invitation’s answered by so few:

o humankind, born for the upward flight,

why are you driven back by wind so slight?”

He led us to a cleft within the rock,

and then he struck my forehead with his wind;

that done, he promised me safe journeying.

xii.94-99

Their climb is reminiscent of that of the Hill of Monte alle Croci, upon which stands the church of San Miniato al Monte, above the Rubaconte bridge, overlooking Florence; the stone cut steps there were made before a time of great scandal in Florence, “in an age / when record books and measures could be trusted” (102-103).

This is an allusion to an incident involving one Niccola Acciaiuoli, a Florentine Guelph who, in 1299, together with Baldo d’Aguglione, in order to destroy the evidence of a fraudulent transaction in which, with the connivance of the podesta, he had been engaged, defaced a sheet of the public records of Florence. And, of a certain Durante de’ Chiaramontesi who, when overseer of the salt customs in Florence, used to receive the salt in a measure of the legal capacity, but distributed it in a measure of smaller capacity from which a stave had been withdrawn, and thus made a large profit on the difference.3

As they climbed, the most beautiful hymn of Beatitude-the first from the Sermon on the Mount-was sung by the Angel of Beatitude, embodying the antithesis of Pride: Blessed are the poor in spirit.

While we began to move in that direction,

“beati pauperes spiritu” was sung

so sweetly-it can not be told in words.

How different were these entryways from those

of Hell! For here it is with song one enters;

down there, it is with savage lamentation.

Now we ascended by the sacred stairs,

but I seemed to be much more light than I

had been before, along the level terrace.

xii.109-117

Dante felt the lightness of his being with the removal of the P and was surprised at the ease of the climb; once this cleansing from pride-which is the first, or root of all the other sins-was complete, even the other P’s have faded. And as that is fulfilled even more,

Your feet will be so mastered by good will

that they not only will not feel travail

but will delight when they are urged uphill.

xii.124-126

As Dante felt his own forehead, trying to find the traces of the P’s still remaining, Virgil smiled.

💭 Philosophical Exercises

Everything is a symbol, even the most piercing pain. We are dreamers who shout in our sleep. We do not know whether the things afflicting us are the secret beginning of our ulterior happiness or not.

~ Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

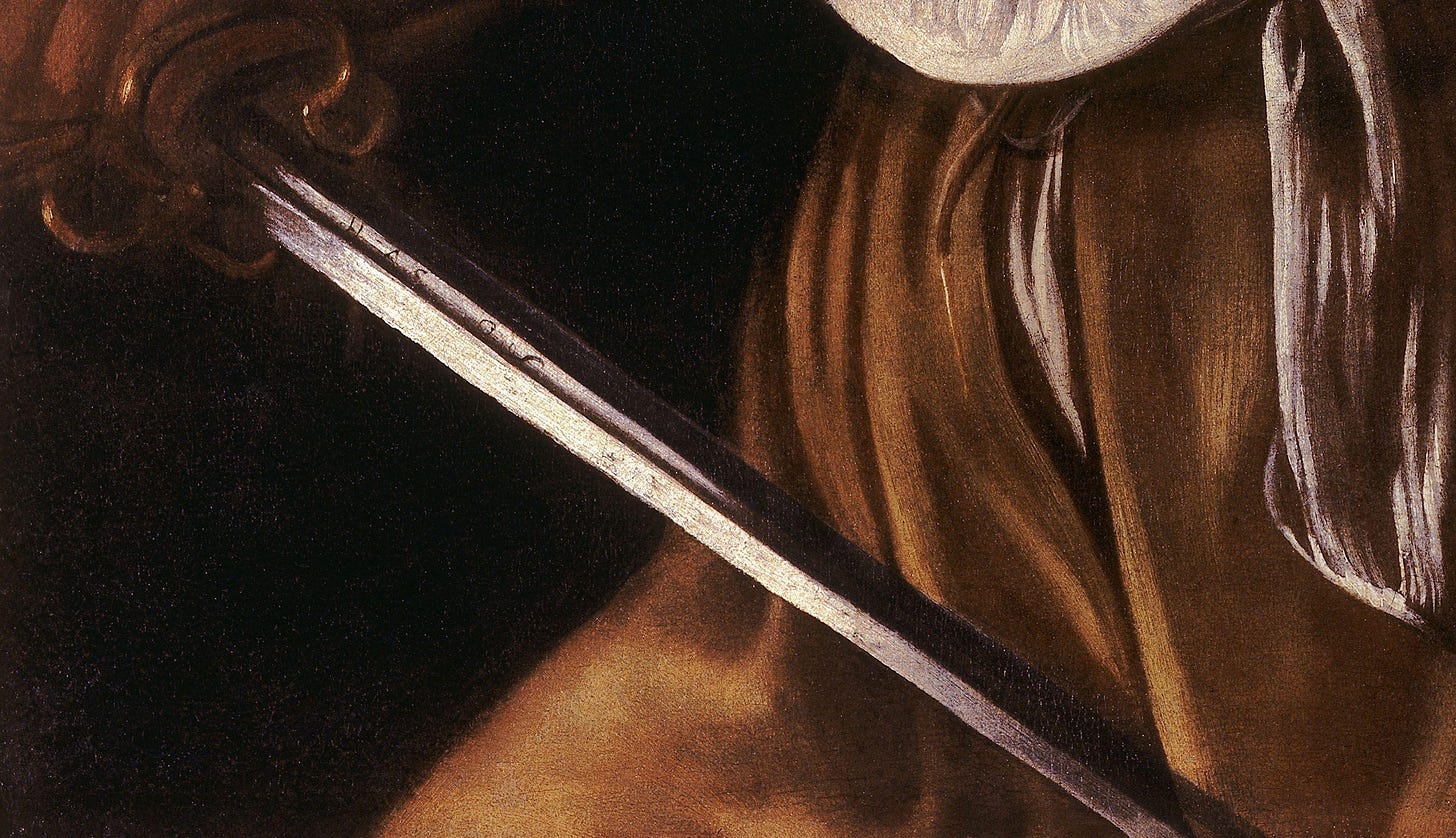

Not many visitors to the Galleria Borghese in Rome notice a small yet profoundly important detail in Caravaggio’s terrifyingly haunting painting.

Most will be told the surface-level story: the dramatic slaying of Goliath, the warrior giant, by the cunning and young David. But was Goliath merely a physical giant, or a metaphorical one? A figure swollen with pride, arrogance, and inflated selfhood? In either case, the smaller, humbler David defeats him in a decisive clash.

Those who would choose to hire a guide will often hear something that is not mentioned in the brief description beside the canvas: that the severed head of Goliath is, in fact, a self-portrait. Caravaggio painted himself as Goliath.

A curious tourist might raise a hand and ask, “Why? Why would Caravaggio do that?” The guide may offer an ambiguous answer, mentioning, perhaps, the murder Caravaggio committed, his exile, or his spiralling inner turmoil.

But only a devoted admirer of Michelangelo Merisi, one who leans in closely, nose nearly touching the canvas, will notice the faint Latin inscription on the blade: H-AS-OS, an abbreviation of Humilitas occidit superbiam—humility conquers pride.

I.

Caravaggio’s Goliath could have easily been placed in Dante’s terrace of the prideful. This canto is imbued with Purgatorial Art once again, but of a different kind. The incredible beauty of this canto is how it is almost architecturally symmetrical. I believe at the root of this symmetry is its leitmotif of the mirror. The art of reflection through opposites.

What makes this passage so compelling is how Dante reveals the duality inherent in human nature, the delicate balance between evil and virtue, shadow and light. The importance of looking not only at the light but also at the dark. But, what exactly do I mean by this?

As we enter the terrace of pride, we first encounter beautiful images carved into the rocks. Then, in this canto, in perfect mirror-like opposition, he observes images carved beneath his feet—much like the tombstones and gravestones one might find carved into the floors of ancient churches and cathedrals. Those who have visited Westminster Abbey, once described by William Morris as ‘The National Valhalla’, might remember the tombs of Stephen Hawking, Isaac Newton, John Dryden and many others who are buried beneath are eternally preserved in quiet grander of stone.

This creates our first mirror image. Where the previous canto showed us the beautiful side of human nature, the ability to conquer pride and achieve humility, this canto presents its opposite reflection. Here we witness the transgressions, the global failures that have marked human history throughout the ages.

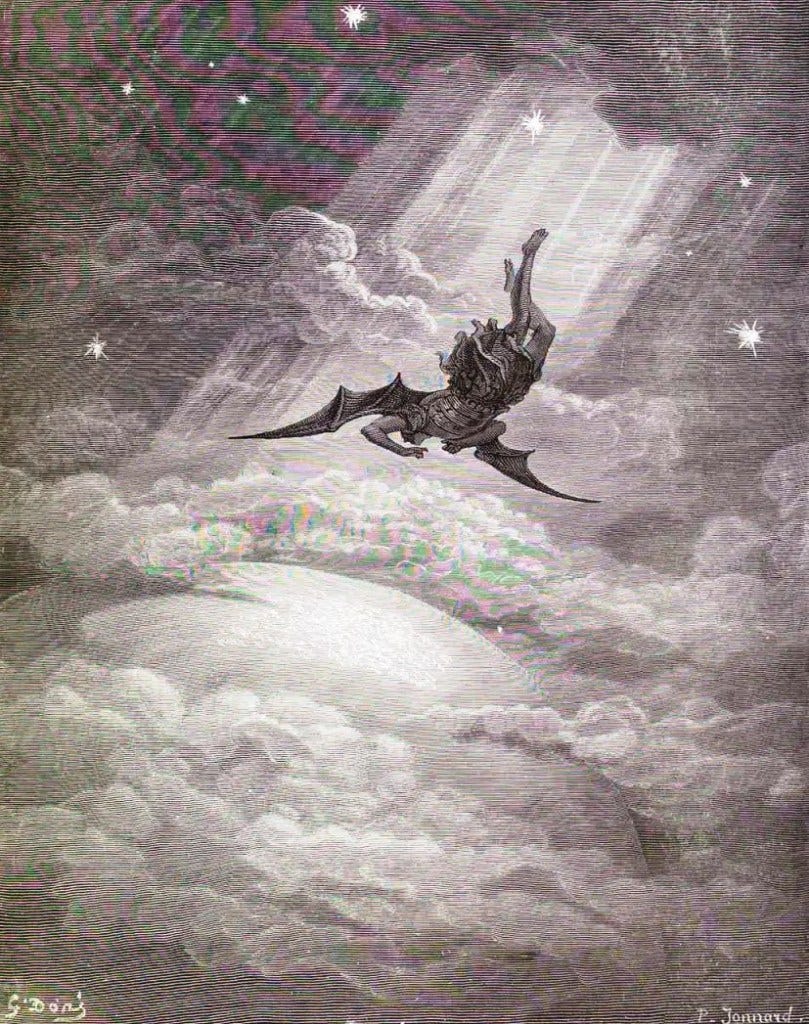

The first and most striking opposition we encounter is Lucifer himself, whom we meet somewhat personally in the previous leg of our journey. One is tempted to draw a parallel between Lucifer and Mary, for if Lucifer rebelled against the monarchy of God, Mary submitted with humility.

While one could certainly explore the broader mirrors between good and evil, I want to focus on the remarkable parallels Dante draws between biblical and pagan examples of pride. There are six such parallels.

The first pair presents Lucifer alongside Briareus. Lucifer, of course, was one of God’s most beautiful angels who rebelled against the divine throne. Briareus, whom we encountered earlier in the Inferno, was the giant who challenged Jove, who dared to contest Zeus’s power. Both represent cosmic rebellion, Lucifer against God, Briareus against the king of the gods.

The second pair brings together King Nimrod and Niobe, both united in their attempts at self-exaltation. Nimrod, the king who believed he could challenge God through the Tower of Babel4, finds his counterpart in Niobe, who compared herself to the goddess Leto, boasting that she had more children than the deity. Their punishments share a common thread, both are brought low and rendered voiceless. Niobe, having lost all her children to Apollo and Diana’s arrows, was transformed by grief into stone, her tears becoming the mountain streams that flow from high peaks.

The third pairing presents Saul and Arachne, representing the fall of once-talented individuals who refused to submit to higher authority and divine order. Saul’s pride led to his downfall and suicide after rebelling against the God of Israel. Arachne represents artistic arrogance transformed—her presumption took the form of challenging Minerva (aka Athena) in weaving. When she produced a brilliant representation of the gods’ love affairs, Minerva, unable to surpass this work of art, destroyed it. Arachne attempted suicide, Minerva curbed her attempt and transformed her into a spider, turning the rope into silk filament.

Next come Rehoboam and Sennacherib, both kings undone by pride. Rehoboam, who inherited his kingship from his father Solomon, lost his kingdom by rejecting wise counsel; when his people asked him to alleviate their tax burden, he ignored the elders’ advice and followed young counsellors who urged him to maintain his authority through harsh measures. Sennacherib, the seventh-century Assyrian king and conqueror, arrogantly defied God during his siege of Jerusalem under King Hezekiah. He sent envoys mocking Yahweh, claiming no god had ever saved a nation from Assyria, and was punished for this hubris.

The parallels continue with Alcmaeon and Troy’s fall. Amphiaraus, one of the Seven Against Thebes, was a prophet who knew the war would be disastrous, so he initially refused to participate. However, his wife, bribed with a necklace (lol)5, convinced him to join. Before dying, he commanded his son to avenge him by killing his wife. When Alcmaeon obeyed, committing this horrific matricide, he was haunted by the Furies and driven into exile and madness. Dante suggests that Alcmaeon presumed to be a moral judge, conducting his own version of justice, a transgression against divine authority.

This finds its parallel in Troy’s fall, where the pride of Priam’s house led them to believe their walls were unbreachable and their kingdom unmatched. Notably, this represents the first pairing where both examples are pagan, linking the fall of Thebes with the fall of Troy through their shared hubris.

The final parallel presents Holofernes and Cyrus the Great. Holofernes, immortalised in paintings by artists like Artemisia Gentileschi, grew prideful in his tyrannical actions and was punished through decapitation by Judith. Cyrus the Great met a similar fate when he was ambushed in Scythia by an enemy queen who not only killed him but decapitated him, placing his head in a vessel of human blood while uttering words that echoed divine judgment.

But Dante’s mirror imagery doesn’t end with these historical parallels. A solitary angel approaches, and as Robert Hollander notes, this angel comes as the morning star Venus—also known as Lucifer. This creates yet another polar relationship to Satan, establishing Venus as love in opposition to the fallen angel’s rebellion.

Throughout this canto, what overwhelms me are these mind-expanding parallels, this constant duality. I believe Dante shows us this coexistence of opposites to demonstrate a fundamental truth about integration—the union of beautiful and ugly, good and evil, light and shadow.

It is never about separation but about understanding wholeness. This, after all, is what it means to reflect, to look in the mirror, to see the multiple versions of yourself, and to unite them in one.

Only this integration guarantees ascent through the mountain. Dante could have easily shown us only the inspiring examples of how humility conquers pride, but he chose a different path. He shows us the parallels instead, suggesting that we must know the dark side to truly comprehend the good.

This is the absolutely beautiful mirror—the genius of Dante’s vision—the recognition that understanding requires both reflection and opposition, that wisdom comes not from avoiding shadows but from seeing how they define the light.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. Letter P being erased

Interestingly, some commentators have noted that when Dante touches his forehead, he doesn’t just feel the P of pride vanish, he senses the deeper healing of the others as well. Once again, we are reminded of the interconnectedness of sin, how one vice does not stand alone but binds itself to others.

In Inferno, sins are arranged concentrically, like a reversed Russian doll from the lesser faults to the gravest. But here in Purgatorio, the order seems to be reversed: we begin with pride, the root of all vice. Perhaps the reason is because pride is the most resistant to change, it is the sin that closes the door to changing our character. To overcome it is to open the path for all other healing.

II. Heavenly Music and Musica Diaboli

While we began to move in that direction,

“Beati pauperes spiritu” was sung

so sweetly—it can not be told in words.How different were these entryways from those

of Hell! For here it is with song one enters;

down there, it is with savage lamentations.~ 109 - 114

Once again, we witness the beauty of music, of heavenly sounds, the path through Inferno was full of painful sighs, the soul-draining noises. Here we feel the harmony, for what is music, if not the well-ordered melodies, and what is noise if not chaos given a voice.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

This invitation’s answered by so few:

o humankind, born for the upward flight,

why are you driven back by wind so slight?”~ 94 - 96

Purgatorio xi.119

Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory 162

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on Purgatorio 262, 264

We won’t pause for long here since we have explored King Nimrod in Inferno.

Although at the first sign it is funny, yet the necklace has a meaning, which would take another paragraph to explain fully.

Does anyone else listen to the music in each canto when they read? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p_5asVhCwH0