When the Student is Ready, the Teacher Will Come

(Purgatorio, Canto IV): Beckett and Dante, Leonardo and the cost of inaction

Iron rusts from disuse; water loses its purity from stagnation... even so does inaction sap the vigor of the mind.

~ Leonardo da Vinci

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

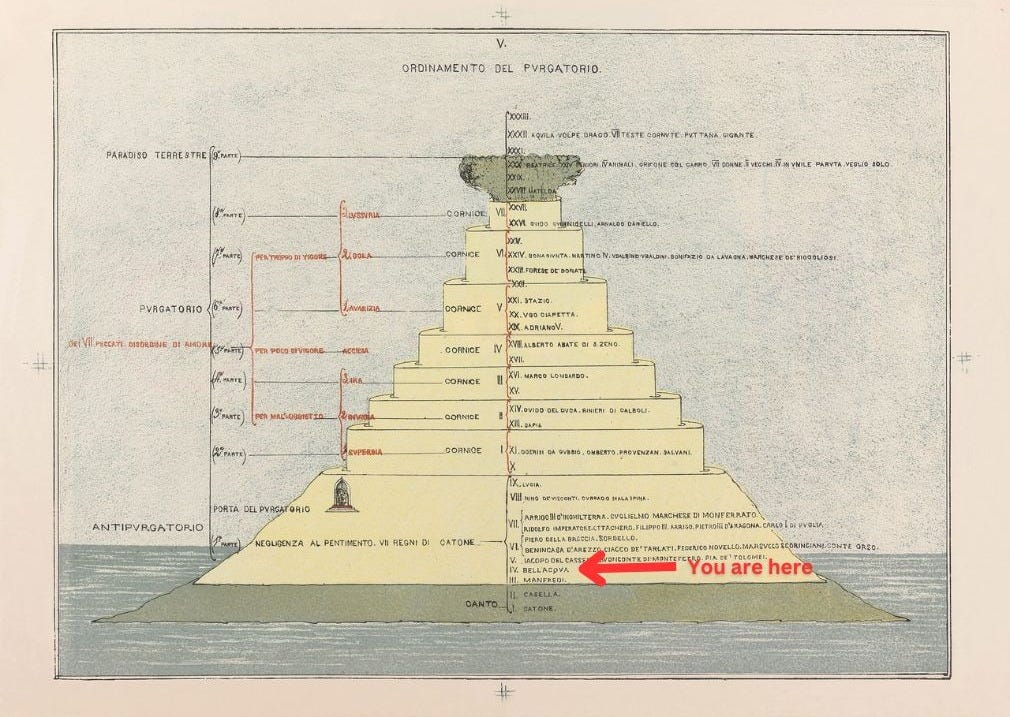

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Fourth Canto of the Purgatorio, we encounter the Late Repentant and hear a treatise on the soul. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Ante Purgatory - The terrace of the Excommunicated - An exposition on the soul - Manfred speaks on - Dante and Virgil begin their climb - The terrace of the Late Repentant - Virgil’s speech on Astronomy in the southern hemisphere - Belacqua the Lazy.

Canto IV Summary:

Still in the first terrace of the excommunicates, Dante begins canto iv of Purgatorio with an exposition on the nature of the soul as held by the Scholastics, a philosophical school in the middle ages that worked to reconcile philosophy with Christian theology, especially via the works of Plato and Aristotle.

The only work of Plato with which Dante would have been familiar is the Timaeus, which held the theory that each person had three distinct and separate souls within them; this is the claim he is refuting in lines 5-6. The attention that Dante gives to Manfred supports instead Aristotle’s theory that the singular human soul is composed of three features:

I say then that the Philosopher in the second book of On the Soul, distinguishing the soul’s powers, says that its powers are principally three, namely living, sensing, and reasoning.

Dante, Convivio III.ii.11

Aristotle moved away from his teacher Plato and taught the singular soul was divided into three faculties; this was later expounded upon by Thomas Aquinas and the Scholastics. These three faculties of soul were the Nutritive, or that relating to the physical growth of the body, Sensitive, or that regarding feeling, and the Intellectual, that guiding rationality and thought. Each of these built upon the other to culminate into the third type, which was unique to humanity. To journey through Purgatory is to examine these philosophical and theological questions that occupied the intellectual minds of the time.

Since all the powers of the soul are rooted in the one essence of the soul, it must needs happen, when the intention of the soul is strongly drawn towards the action of one power, that it is withdrawn from the action of another power; because the soul, being one, can only have one intention. The result is that if one thing draws upon itself the entire intention of the soul, or a great portion thereof, anything else requiring considerable attention is incompatible therewith. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica1

Dante’s attention was so taken by Manfred, that he confirmed the strength of the concentration of one part of the soul, while the others retreated into the background:

The power that perceives the course of time

is not the power that captures all the mind;

the former has no force—the latter binds.

And I confirmed this by experience,

hearing that spirit in my wonderment;

iv.10-15

This underlying unity of both mind and senses (including the perception of time) is proved by the fact that his own mind’s total concentration on Manfred overpowered his awareness of the passage of time.2

As Dante notes spending an extended period of time listening to Manfred — over 3 hours, based on the fifty degree movement of the sun in the sky — it would do us well to look more closely at the architecture of Ante Purgatory.

The first terrace was that of the Excommunicated, those denied participation in the sacraments by the church due to their infidelity or for other reasons. This is where Dante and Virgil presently stand, as they listen to Manfred.

The next terrace contains the Late Repentant, and of those we will encounter three types, the first of which is here in canto iv. Their punishments all revolve around waiting to be admitted to Purgatory proper.

First are the Indolent, those who were within the good graces of the Church, but did not repent — the secondary sense of the act of confession — during life, and waited until their dying moment to do so. These were serial procrastinators, surely not thinking that overlooking such a small thing would have such consequences.

Second are the Unshriven, or those who died suddenly or violently and had no time to confess or repent fully before death; yet the did repent at the very last moment in what way they could.

Last are the Pre-Occupied, those who loved the world and it’s delights too much to make time for righteous living; this differs from the Indolent, as the first group was beset by laziness, this third group, by preoccupation with other things over the importance of attention given to their spiritual lives.

Now that the architecture has been noted, and the nature of the delay as Dante has listened to Manfred understood, let us engage with the story.

Those sheeplike souls who had been following Manfred caught Dante’s attention, for they cried out as one — still, this Purgatorial unity — “Here’s what you want” (18), indicating the way forward.

Using a more humble simile than the Homeric form to which we have become accustomed, Dante explains the way that has been pointed out to them:

The farmer, when the grape is darkening,

will often stuff a wider opening

with just a little forkful of his thorns,

than was the gap through which my guide and I,

who followed after, climbed, we two alone,

after that company of souls had gone.

iv.19-24

The farmer, to protect his ripening crop, will block any opening in the hedge surrounding his cultivation — no matter how small — with “a little forkful of thorns,” to prevent thieves from stealing his crop, indicating just how small a gap they had to climb through.

Enter ye in at the strait gate: for wide is the gate, and broad is the way, that leadeth to destruction, and many there be which go in thereat: Because strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.

Matthew 7:13-14

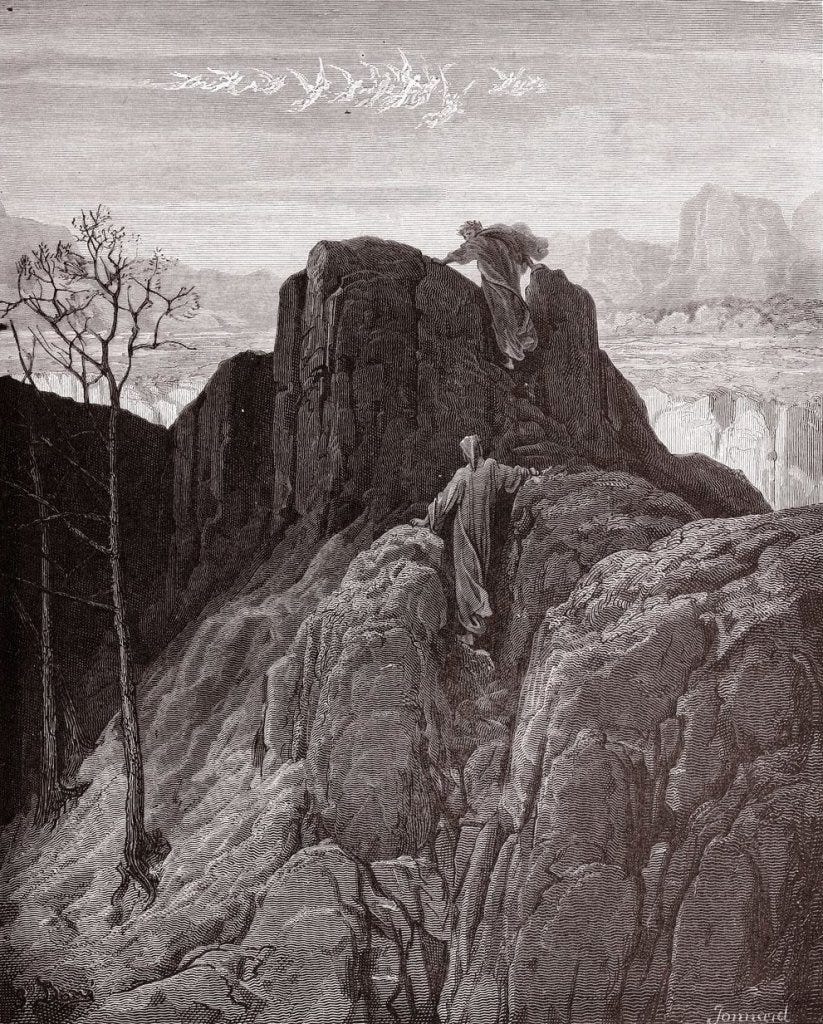

Not only was the way impossibly small, it was also threateningly steep and seemingly impassable, just as the paths to the towns of San Leo and Noli, both of which were situated upon precipitous mountain ridges like the mountain peak of Bismantova. In order to undertake such a climb, that climber must have both a guide and an intense desire:

But here

I had to fly: I mean with rapid wings

and pinions of immense desire, behind

the guide who gave me hope and was my light.

iv.27-30

Once through the cliff, Dante stopped to reassess and ask the way forward. Virgil responded with an admonition to keep to the task at hand, to continue on to the goal they had already set; even if the way was unsure, moving forward was the only best option;

And he to me: “Don’t squander any steps;

keep climbing up the mountain after me

until we find some expert company”

iv.37-39

In truth, it was intimidating; the angle of the Mount before them was more than 45°, “far more steep than the line drawn / from middle-quadrant to the center point” (41-42). Even as Dante, in his exhaustion, begged for a pause, Virgil pointed to a terrace above them, one that ran around the Mount, and encouraged Dante to make it that far. Just as Cato had pushed them on to beginning their journey, this is the first of many times that Dante is encouraged to go a little further.

They surveyed the heights from which they had come; “what joy - to look back at a path we’ve climbed!” Here, the sense of accomplishment was palpable, a notable feeling in Purgatory. One thinks of the difference in looking back with accomplishment versus looking back in longing, or for those things of old.

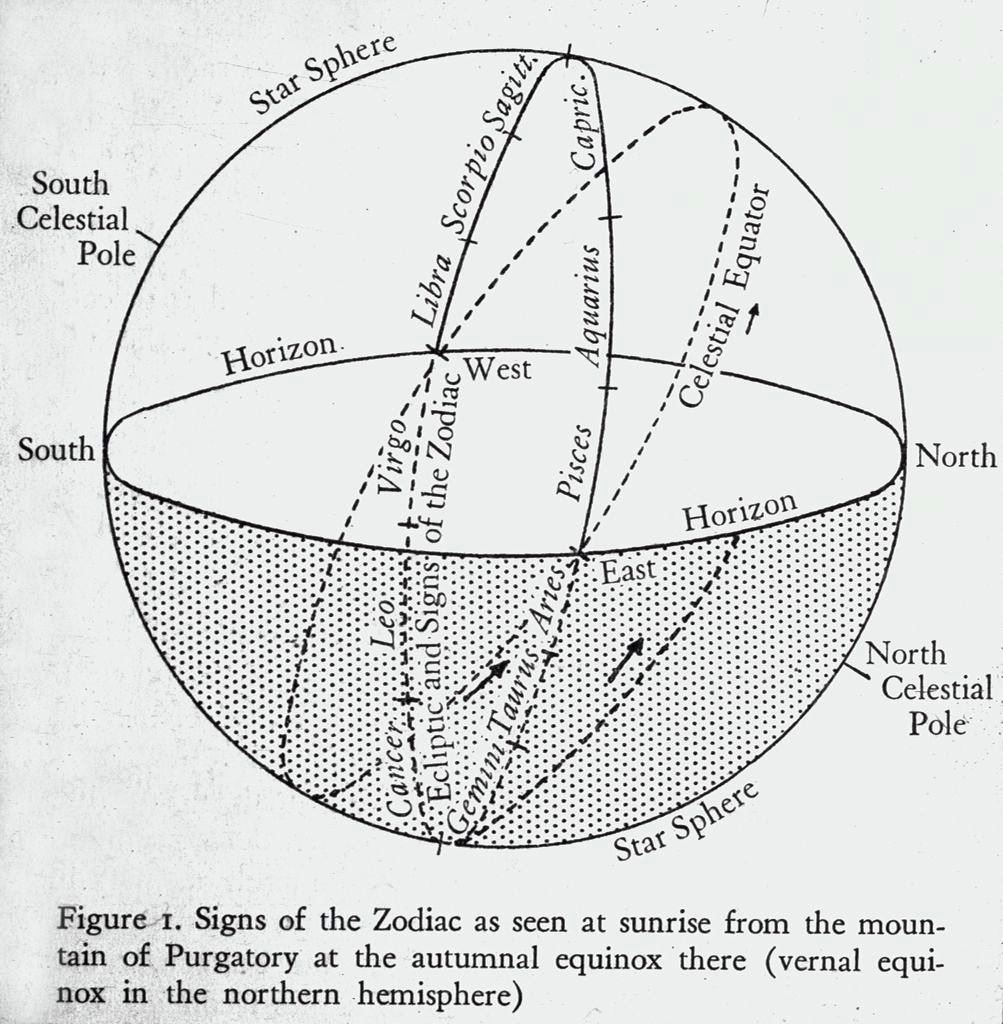

Just as in the exposition on the soul in the opening lines of canto iv, here begins an exposition on astronomy in the northern versus the southern hemisphere. Dante expresses his amazement that the sun, here below the equator, is in a different position than he would have expected it to be in the north.

But the shadow of people, if such there be, who are separated from us by the heats of Libya falls to the South, whereas ours falls northward.

Lucan Pharsalia ix.538-39

If Castor and Pollux (stars in Gemini) were in company with that Mirror (the sun) which carries his light up and down (i.e. goes north and south alternately), you would see the glowing zodiac (the part in which the sun is) revolving still closer to the Bears (the north in general).3

To take the consideration even further, Virgil then goes from the heavenly arrangement to the geographical arrangement, all still explaining, in this scientific aside, why Dante saw the shadows falling differently than expected as they were sitting to rest:

Mount Zion (Jerusalem) being a the exact center of the northern hemisphere, and Mount purgatory at the center of the southern hemisphere, the two mountains are on directly opposite sides of the earth and thus have a common horizon midway between them, which passes through Ganges in the east and Gibraltar in the west. It is assumed that Dante the character (and the reader) will have in mind the fact that Zion is north of the Tropic of Cancer and Mount Purgatory is south of the Tropic of Capricorn.4

Dante not only agrees with all of Virgil’s statement, but then goes on to reiterate, to narrate back to him, what he has just said in Dante’s own words:

I said: “My master, surely I have never —

since my intelligence seemed lacking — seen

as clearly as I now can comprehend,

that the mid-circle of the heavens’ motion

(one of the sciences calls it Equator),

which always lies between the sun and winter,

as you explained, lies as far north of here

as it lies southward of the site from which

the Hebrews, looking toward the tropics, saw it”

iv.76-84

His curiosity satisfied, and now more rested, he still wonders how far they will have to journey up the mountain, as he cannot even see the top. Virgil explains that the further they journey, the easier their climb will become, both literally and figuratively; the terraces will become, as we shall see, smaller, the higher they climb, though not less steep. The real ease will come as he becomes lighter through the purification of body and soul and his gaining of virtue, making the climb feel effortless;

And he to me: “This mountain’s of such sort

that climbing it is hardest at the start;

but as we rise, the slope grows less unkind.

Therefore, when this slope seems to you so gentle

that climbing farther up will be as restful

as traveling downstream by boat, you will

be where this pathway ends, and there you can

expect to put your weariness to rest.

I say no more, and this I know as truth.”

iv.88-96

The first soul encountered in this terrace of the Late Repentant makes himself known at this junction with a sarcastic remark coming out of nowhere; here we meet Belacqua. Little is known of this almost comedic character, except that he was a craftsman of musical instruments whom Dante knew in Florence; he has sometimes been identified as Duccio di Bonavia.

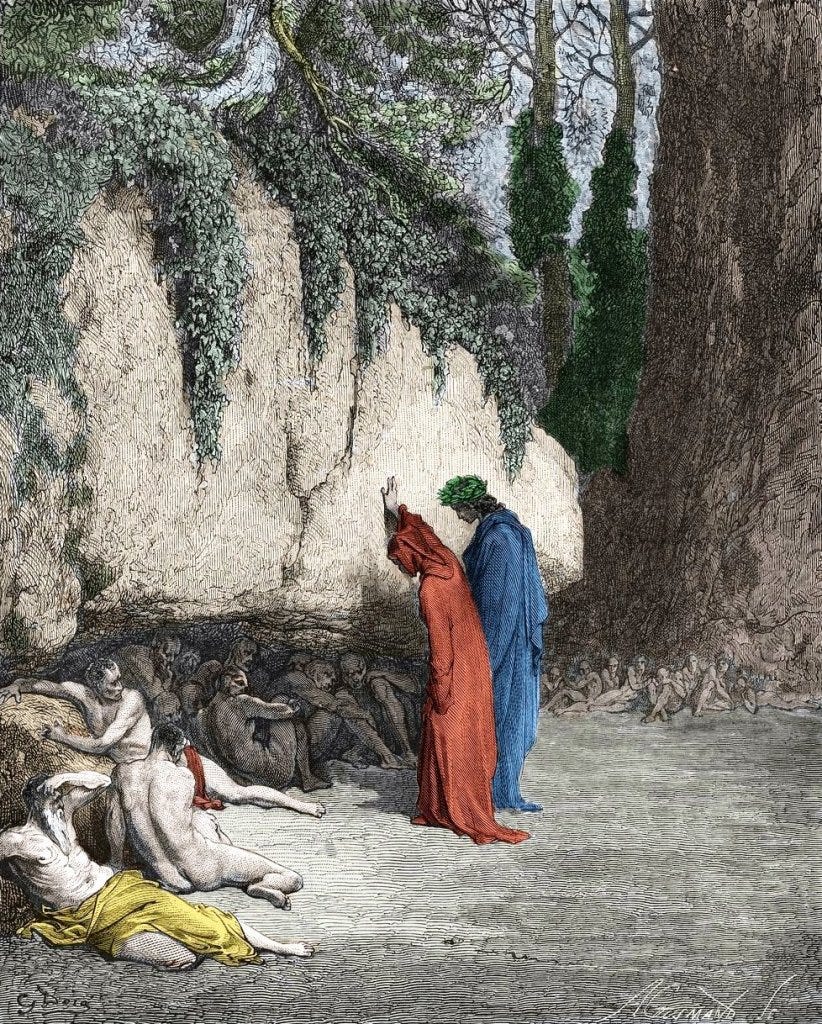

Contrast the weariness of Dante, who has just made a difficult climb and also holds the prospect of more difficulty before him, with the weariness of these indolent, who, doing nothing, are nevertheless exhausted. They follow the sound of the sarcastic voice:

We made our way toward it and toward the people

who lounged behind that boulder in the shade,

as men beset by listlessness will rest.

And one of them, who seemed to me exhausted,

was sitting with his arms around his knees;

between his knees he kept his head bent down.

iv.103-108

Dante is not shy in pointing this one out as “one who shows himself more languid than / he would have been were laziness his sister!” (110-111)

When Belacqua raises his head, then Dante recognizes him; as he moves toward him, Belacqua again makes a sarcastic quip, as one who knows it all and is scornful of anyone and anything that tries to show differently.

With this question, the lazy spirit makes a little fun of Dante, who is trying so hard to understand how the sun can be on his left; and with that he reveals not only material, but spiritual negligence as well: he has no curiosity of that sort! He has not even felt the curiosity to find out why a living man should be there climbing the mountain.5

Yet Dante is only amused, not offended; even the words that Belacqua is using are short — lazy — driving home the point even more. Dante jests that now that he knows Belacqua is in Purgatory, he will not have to worry where he ended up; indicating that it may not have been a surprise to see him in Inferno instead. Upon being asked why he is just sitting, while so far they have only seen souls eager for movement, Belacqua gives both his own reasoning and the explanation of the circumstances of those in the terrace of the Late Repentant:

And he: “O brother, what’s the use of climbing?

God’s angel, he who guards the gate, would not

let me pass through to meet my punishment.

Outside that gate the skies must circle round

as many times as they did when I lived -

since I delayed good sighs until the end -

unless, before then, I am helped by prayer

that rises from a heart that lives in grace;

what use are other prayers - ignored by Heaven?”

iv.127-135

Where the excommunicate could not advance until they had waited for thirty times the length of their excommunication, here, the Late Repentant indolent must wait for the length of their lives on earth, unless helped along by the prayers of the living. Belacqua indicates that there is no one praying for his quick advancement; perhaps because he was so divisive in life, he did not leave behind anyone who was in sympathy for him.

In hell there had been no such beat of rhythm; all there was monotonous mirk, but here the movement is ordered. Time itself is blessed, as with the spirits whom they meet at first, and who have either died excommunicate or have postponed repentance till death, till almost too late. The first kind linger thirty times the length of the ban; the second as long as their lives lasted. Those who delayed have to delay, but the invention urges on the reader their desire towards the purging. They are left, so long, with their images unpurged—disconsolate in that sustained state, they endure patiently their old procrastination.6

Virgil has no time for the expositions of Belacqua, especially after already having lost time to Manfred. He is already off, beckoning Dante to follow; the sun is at its peak, it is noon; at home in the northern hemisphere, night has fallen.

💭 Philosophical Exercises

Nature knows no pause in progress and development, and attaches her curse on all inaction.

~ Goethe

“All I want is to sit on my ass, and fart, and read Dante,” said the Nobel Prize–winning Irish author Samuel Beckett.

At first, I had second thoughts about even including this quote in my post but then I discovered that Beckett, whose works are saturated with impersonal, tragicomic, existential themes, had modelled himself on Belacqua.

At first glance, Belacqua appears to be a minor secondary character—he speaks only a few lines. But Beckett took this seemingly marginal figure and pushed him to the extreme. He not only modelled himself on Belacqua as a passive figure who deliberately withdraws from the world and remains indifferent to life—he embraced this attitude as a philosophy. In fact, he turned it into an aesthetic choice: his first novel features a character named Belacqua Shuah.

Beckett’s Belacqua is not merely lazy, he consciously chooses mundane tasks as life’s priority, actively denying the existence of any higher meaning. He embraces passivity as a deliberate philosophy.

Even his death reflects the characteristic Beckettian and Belacquan wit: the character dies from a minor surgical procedure, so trivial it was hardly worth undergoing in the first place. In this final moment, too, we witness the same dry irony, he transitions from life to afterlife with the same indifferent detachment that defined his existence.

This is why, in the end, I decided to include Beckett’s quote, despite its crudeness because, on reflection, it’s infused with the very same indifferent wit that defines Belacqua himself.

It is infused with what Greeks called Acedia…

I. Do you suffer from acedia?

The Greek term ἀκηδία (akēdia) derives from the prefix "a" (without) and "kedos" (care). One of the characteristics of acedia, according to the desert fathers, is inability to remain present, causing one’s mind constantly to seek distraction and escape.

John Cassian, who has a lovely work on how to focus (which I explore in my video here), described acidea as:

“The demon of acedia instills in the monk a hatred for the place, a hatred for his cell, and a hatred for labor. It makes him lazy and sluggish about any kind of work. He cannot stay still in his cell or devote any effort to reading.”

— John Cassian

The opposite of Acedia is diligence, a practice that shows us that the meaningful human life requires commitment and effort sustained over time, especially when immediate emotional gratification is absent.

Medieval thinkers believed that we should keep a close eye on our inner climate, for our cognitive states play a crucial role in whether we achieve our aims or not.

Cassian himself traveled across Christendom, seeking out prominent scholars to learn techniques for maintaining focus. One of the most important pieces of advice he received was to always keep one’s eye on the telos—the ultimate goal—and never let go of it.

But perhaps the deepest reason why acedia was so greatly feared in Dante’s time—and even earlier—is that acedia is not merely sloth or laziness. It drains the motivational essence from our goals. If the personification of sloth says, “It’s too difficult—don’t do it,” acedia whispers, “It’s not only difficult—but pointless to even try.”

II. Unity of our Soul and The Power of Will

When any of our faculties retains

a strong impression of delight or pain,

the soul will wholly concentrate on that,neglecting any other power it has

(and this refutes the error that maintains

that—one above the other—several soulscan flame in us); and thus, when something seen

or heard secures the soul in stringent grip,

time moves and yet we do not notice it.

Dante begins this canto by telling us about the unity of our soul. In contrast to Plato, who believed that our soul consists of several parts, Dante and Aristotle believed that we have one unified soul with several faculties and sub-faculties.

Dante’s brief yet profound argument here is that the soul must be unified, when one part of it is wholly concentrated on a task, the other faculties recede into the background. Reflecting on this now, I realise that while writing this post for you, I became so deeply engaged and engrossed that I lost all sense of time. It is now already a quarter past midnight.

It’s worth weaving together the philosophical messages Dante has laid before us so far, as they are remarkably rich. In the first canto of Purgatorio, Dante, and we, as his readers, were washed clean of Inferno’s tears, ready to begin anew. In the second, Cato reminded us not to substitute real progress with illusion, as seen in the scene with Casella’s song. In the third canto, Dante’s reason and faith began to unify, each strengthening the other.

Now, in the opening of this fourth canto, Dante explicitly speaks to us about the unity of the soul. But what, then, is the philosophical focus of this canto?

The power of will.

Throughout this canto Dante wants to rest. It is the most frequent word used in this scene. Dante wants to rest and asks how much is left. In this part, where Virgil and Dante climb together we see how reason and our soul act in the unity together. Dante sees the highest point that he must reach thus giving him a direction and Virgil, our Reason, tells his companion:

“My son,” he said, “draw yourself up to there,”

while pointing to a somewhat higher terrace,

which circles all the slope along that side.(lines 46-48)

My reader must have noticed that Virgil does not teach his “son”, he inspires him. He offers Dante a foothold, allowing him to lift himself up. The use of the word “son” is, of course, deeply significant. In the Christian worldview, God is our Father, and therefore, by aiming ourselves toward Him, we rise.

The whole canto is a dance between our reason and our soul in harmony, for when Dante looks up at the celestial motions in confusion, Virgil gives him a deep explanation, but what is interesting is not how Virgil explains, and not even the meaning behind his words, but how Dante re-phrases what his guide explained with his own words:

I said: “My master, surely I have never—

since my intelligence seemed lacking—seen

as clearly as I now can comprehend,that the mid—circle of the heavens’ motion

(one of the sciences calls it Equator),

which always lies between the sun and winter,as you explained, lies as far north of here

as it lies southward of the site from which

the Hebrews, looking toward the tropics, saw it.

Reason explains; the soul comprehends. We’ve all experienced this: reading a great author who subtly unveils deep and profound truths, and suddenly we exclaim, “Aha! Now I get it!” and then we go on to explain the meaning in our own words, shaped by how we’ve arranged the knowledge within our consciousness. Once again, this reveals the inter-action between reason and the soul.

In Purgatorio, we are called to take action. We must climb an inscrutable mountain whose summit remains hidden from view. Even in the scene with Casella’s song, Virgil and Dante rebuke themselves for their inaction for lingering too long and needing Cato’s intervention to continue. In Inferno, Dante was a passive observer; he did not have to climb but merely slipped further and further downward. In Purgatorio, by contrast, Dante must engage, must act. In Inferno, we were asked to be fearless; in Purgatorio, we are asked to be courageous.

Belacqua, whom our companions meet in this canto, stands in stark contrast to Dante. His existence is marked by inertia; one might even find it unjust to see him here, full of indolent hope, while Virgil remains confined to Limbo. If Dante’s soul is unified, with its faculties reinforcing one another and growing stronger through harmony, Belacqua’s soul is fragmented—its faculties work against each other, weakening rather than supporting.

The souls of Dante and Belacqua can be likened to the difference between good and bad friends. The former lift each other up in moments of weakness, offering strength and encouragement on the path toward the good; the latter pull one another down, ensuring that none of them ever rise.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. When the student is ready, the teacher will come.

When we had reached the upper rim of that

steep bank, emerging on the open slope,

I said: “My master, what way shall we take?”And he to me: “Don’t squander any steps;

keep climbing up the mountain after me

until we find some expert company.”

When the student is ready, the teacher will come. Dante teaches us that the first step always must be ours. Once again a profound wisdom from Dante through the words of Virgil.

One of the elements of passive life and of a lazy mind is to expect that someone will come and help you, someone will come and teach you how to take the right action, and then, of course, you will do it. Yet this is the very form of being passive, you expect someone will come and help you, but first you must make yourself worthy of it.

Virgil tells Dante to climb as much as he can, however difficult it is, when they reach the right height, an expert company will appear.

Incredible!

II. Armenian “Belacquan” joke

I suppose Belacquan wit is inescapable here. It reminds me of an old Armenian joke:

A man is drowning in a lake and prays fervently to God to come and rescue him. As he clings to hope, a log floats by. He looks at it and says, “No, I’ll wait for God to save me.”

Soon after, a fisherman rows by in a small boat and calls out, “Grab my hand! I’ll pull you in!”

The drowning man shouts back, “Take your filthy hands off me and sail away with your shabby boat! I’m waiting for God!”

A third rescuer comes along, and again, the man refuses.

Eventually, he drowns. When he arrives before God, he asks, “Why didn’t you save me? I prayed with all my heart!”

God replies, “I sent you three rescuers… you turned them all away.”

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

And he to me: “This mountain’s of such sort

that climbing it is hardest at the start;

but as we rise, the slope grows less unkind.Therefore, when this slope seems to you so gentle

that climbing farther up will be as restful

as traveling downstream by boat, you willbe where this pathway ends, and there you can

expect to put your weariness to rest.

I say no more, and this I know as truth.”

I-II, q. 37 a. I, response

Allen Mandelbaum, Purgatorio 634

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on Purgatorio 82

Singleton 84

Singleton 89 quoting the commentator Porena

Charles Williams, The Figure of Beatrice 152