Why Was Walt Disney Buying Books in Nazi Germany?

... or how Caspar David Friedrich's paintings and the German Romantic movement inspired Disney's Bambi.

In the summer of 1938, Walt Disney received an honorary doctorate from Harvard University. At the banquet dedicated to that occasion, another notable figure was present: the author of great novels such as Buddenbrooks and The Magic Mountain—Thomas Mann

Mann also received an honorary doctorate award on that day and during the dinner he happened to take a seat next to Walt Disney. He brought to his companion’s attention the book written by Felix Salten about the adventures of a young deer called Bambi.1

My reader can guess what fruits were borne of Mann’s suggestion. Disney’s mind became infused with imagination when he read the story. He went to his company’s library, which was filled with the German picture books, and handed all of them to his animators. The tale of the young deer, Bambi, had to be steeped in the essence of German Romanticism.

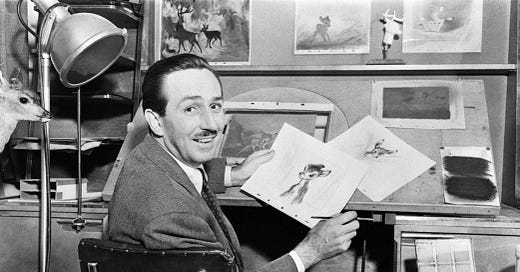

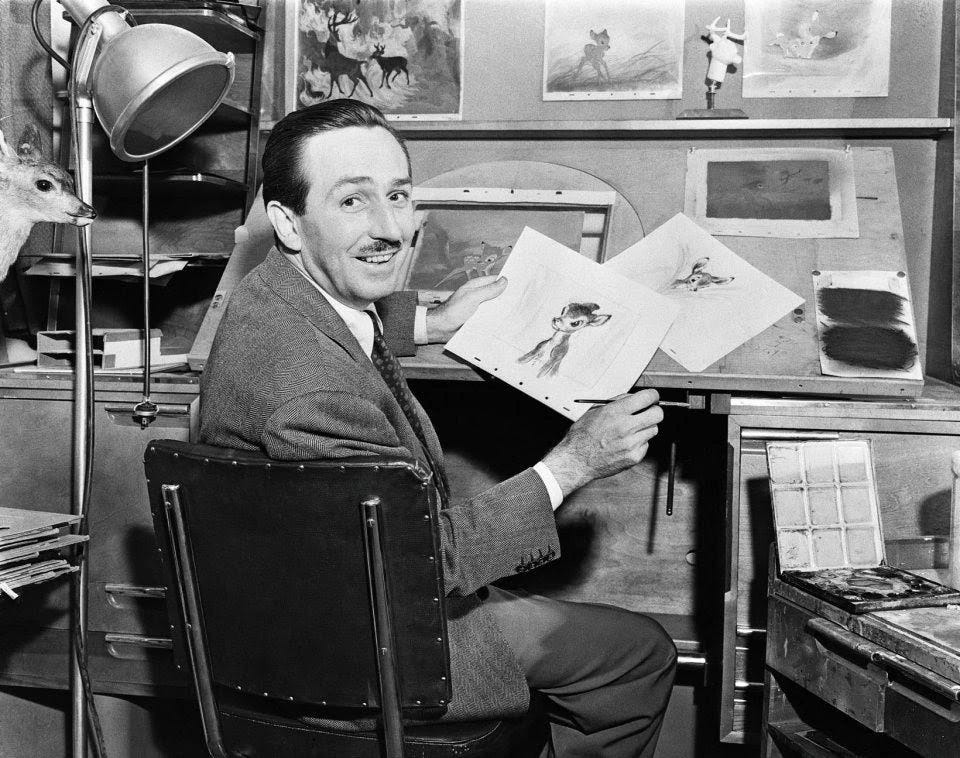

Three years before the event, in the summer of 1935, Disney traveled to Munich and checked into the Hotel Grand Continental. He came to the Third Reich for the screening of his full-length animated film 'In the Realm of Mickey Mouse’.2 As an avid bibliophile, Disney could not miss the opportunity to visit the city’s famous bookshops while he was there.

He went to Christian Kaiser in the Rathaus and to Hungendubel in Marienplatz3. We can only assume that these booksellers could not believe their luck since, according to the historian Florian Illies, Disney bought 149 picture books and illustrated volumes on that day.

Disney was inspired by the German illustrators as well as Romantic painters such as Ludwig Richter and Caspar David Friedrich. In 2011, I stayed in the small town of Meissen in Saxony, where one can find the house of Ludwig Richter. At the time, my mind was consumed by fleeting aspects of popular culture, leaving me unaware that I was in the very town where one of the great German Romanticists once lived.

If my twenty-one-year-old self cannot be excused for lacking the maturity to appreciate something greater, my four- or five-year-old self can. Because it was around the age of five when I first saw Walt Disney’s Bambi, and of course at that time I had no clue who Caspar David Friedrich was and how he influenced one of the most heartbreaking films I have ever seen as a child. Nevertheless Friedrich’s, as well as Richter’s, ‘fingerprints’ are everywhere in that wonderful cartoon.

After reading this story in Illies’s wonderful new book ‘The Magic of Silence’ on Caspar David Friedrich’s life, I paid for a Disney+ subscription and re-watched Bambi for the first time in over three decades.

I genuinely could not believe my eyes. Could my love for Friedrich’s art as an adult be explained by my love for Bambi as a child? As is often the case, our tastes are shaped by unconscious connections.

For copyright reasons, I cannot include direct comparisons between Bambi’s animation and Friedrich’s art. However, if you choose to re-watch it, there are specific paintings you can keep an eye out for they directly influenced the iconic story.

The first one is ‘Morning Mist in the Mountains’ which I added on top of this piece. In one of the earliest scenes, we can see melancholy foggy mountains which so resemble the German landscape.

Another one is ‘Rocky Landscape in the Elbe Sandstone Mountains’, this is where the key characters flee when followed by the hunters. If we closely observe the hues used by the German landscape genius to depict the sky, it becomes clear that they undoubtedly inspired the animators at Walt Disney Studios.

We especially see this if we take a closer look at Friedrich’s work called ‘The Giant Mountains’.

Bambi was neither the first nor the last time Walt Disney drew inspiration from German art. In a 1940 musical anthology film Fantasia we can see another reference to the German culture, this time to the great poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

The third ‘chapter’ of the film begins by the musical piece by the French composer Paul Dukas called The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Dukas music is followed by wonderful animation in which Mickey is the apprentice of an Egyptian sorcerer named Yen Sid. When his master leaves the room, Mickey attempts to practice magic on his own but quickly loses control.

At the very moment when all seems lost, Mickey’s master returns and dispels the spell, restoring order to the chaos caused by his foolish apprentice.

Those of you who have read my two posts on Goethe’s tragic play called Faust (Archetypes of Creativity and Goethe: Science and Alchemy ) will understand what I mean when I say that The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is an astonishingly German story.

That magic encounter of Thomas Mann and Walt Disney ended positively and gifted us one of the most beautiful animations in history. Felix Salten’s career, however, did not have a happy ending at all.

When the book-burning began on 10 May 1933, Felix Salten’s Bambi was one of the first books to be thrown on fire.

The Jewish author Salten had allegorised the desperate situation of the Jews in the story of a fawn fighting for his life.4

When Bambi came out in the middle of the war in 1942, Adolf Hitler was one of the first people in the world to watch it.

The records show that he found it moving.

Proofread and edited by Lisa Statler

This post was inspired by Florian Illies’s recent book The Magic of Silence. I would like to thank all of my paid subscribers, which made it possible for me to purchase this book.

Florian Illies, The Magic of Silence, page 19 (2024)

Florian Illies, The Magic of Silence, page 20 (2024)

ibid.

ibid 21

I loved Florian Illies’s 1913. As usual, you write a resoundingly interesting piece Vashik. 🙏