You Must Change Your Life

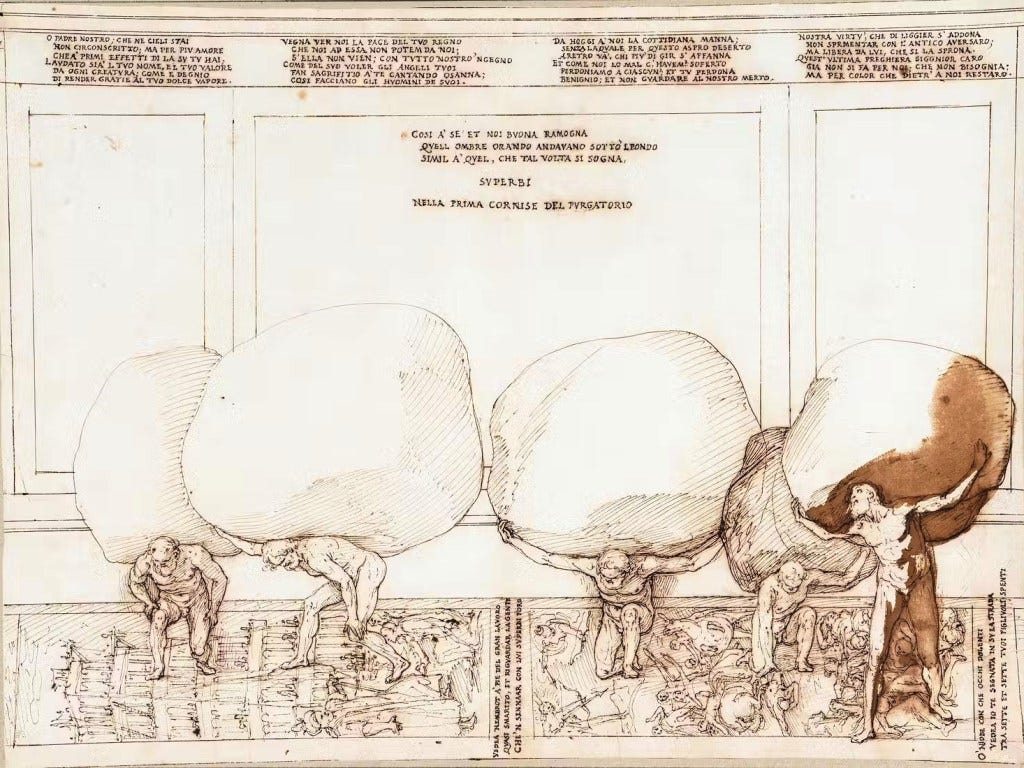

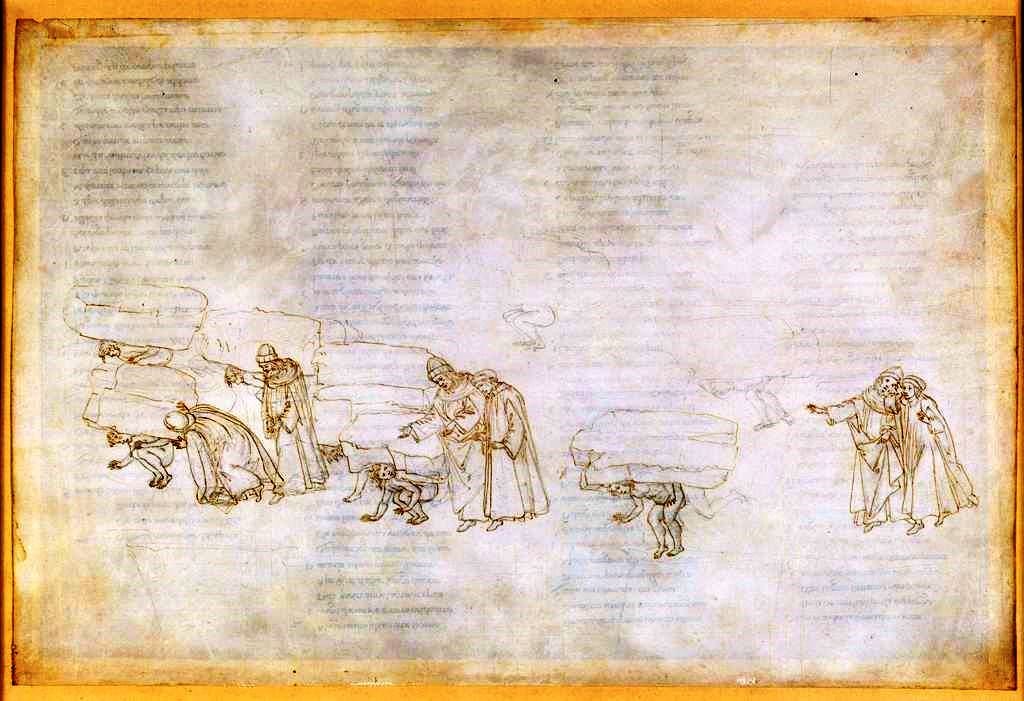

(Purgatorio, Canto XI): Prideful, Oderisi, Provenzano,

The most terrifying thing is to accept oneself completely.

~ Carl Jung

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

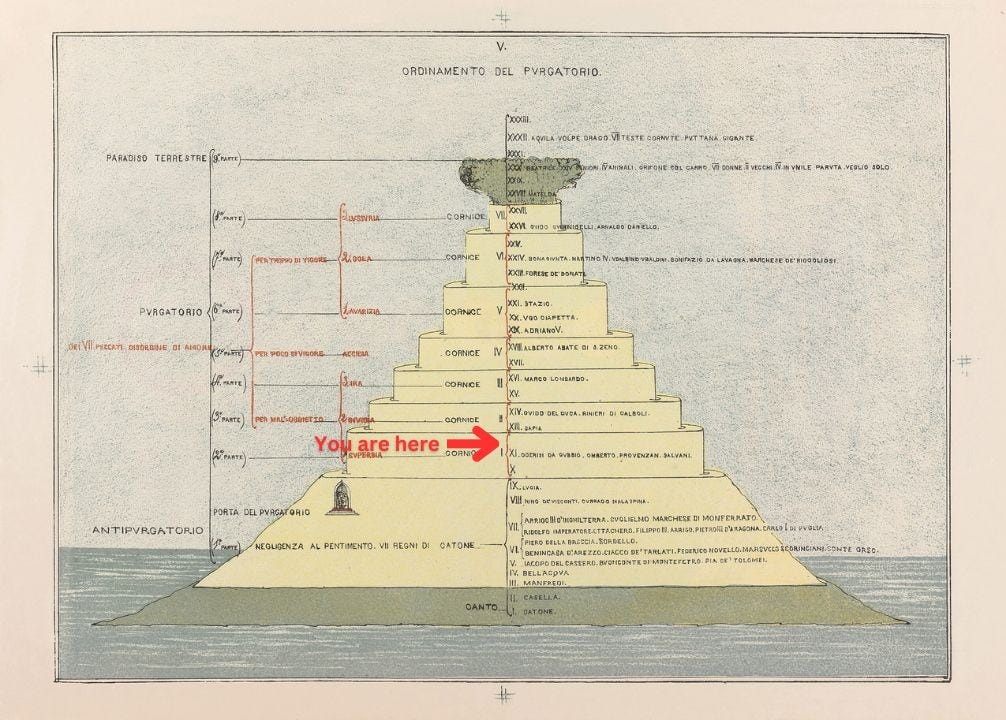

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Eleventh Canto of the Purgatorio, we hear Dante’s extended Lord’s Prayer. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

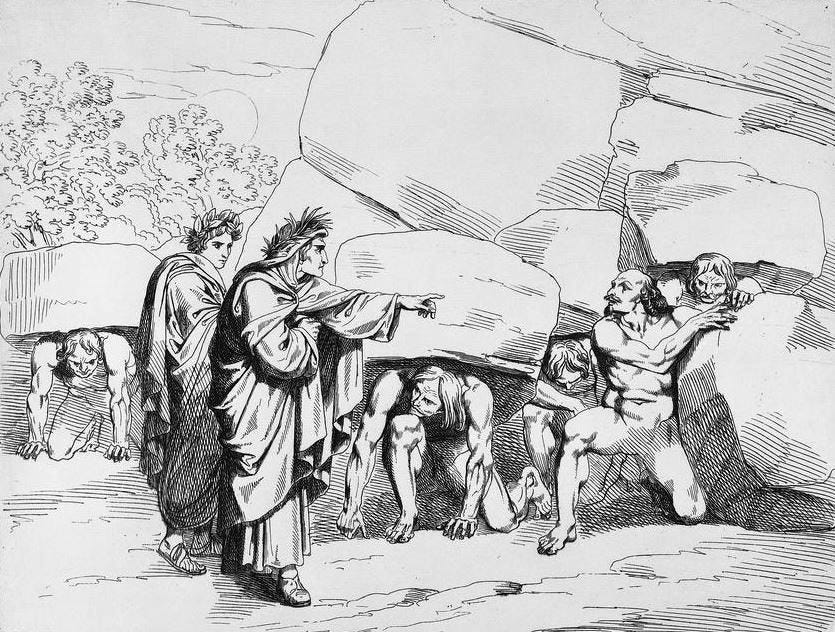

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

An extended Lord’s Prayer - The first terrace continued - The Proud with heavy stones weighing down their backs - Virgil asks the way up the mountain - Omberto Aldobrandesco - Oderisi of Gubbio - The fleeting nature of fame - Provenzan Salvani.

Canto XI Summary:

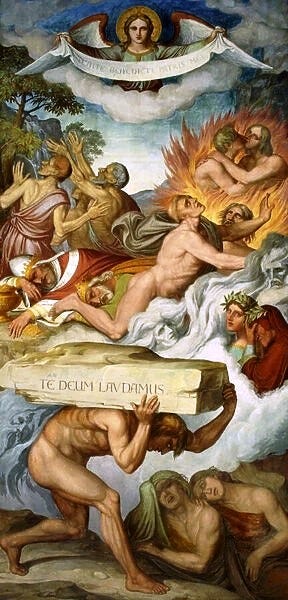

Canto xi opens with an elaborate and extended version of the Lord’s Prayer said by the penitent souls of the Proud, who are weighed down by the massive stones on their backs. They say this prayer not only to cultivate humility for themselves—the virtue of this terrace for which they are striving—but also for the benefit of all beings:

This expanded paraphrase of the the Lord’s Prayer, a verse or clause of which is rendered by each tercet, occupies seven tercets, which correspond in number to the seven terraces of Purgatory, to the seven sins that are purged thereon, and to the seven virtues that oppose those sins. This is the only prayer in the poem which is recited in its entirety.1

The first line of each tercet—group of three lines—corresponds, for the most part, to the lines of the prayer that are so familiar; the remaining lines of the tercet are of Dante’s own expansion of the idea so presented. Each grouping is “directed throughout to the virtue of Humility.2

In the first tercet, God is not circumscribed by the heavens by virtue of limitation or restraint into one area of space, or by being bound to a specific place, but because of his great love for those first works, of the celestial realms and angelic beings who were created before the things of earth.3 (Our Father who art in heaven).

In tercet two, the “sweet emanation” that exudes from God is to be thanked in equal proportion as his name is to be praised (Hallowed be thy name).

For Wisdom is an aura of the might of God and a pure effusion of the glory of the Almighty; therefore nought that is sullied enters into her. Book of Wisdom 7:25

In the third and fourth tercets, Dante expands upon the claim that the peace of God comes to one externally, (Thy kingdom come) and that humanity is unable to reach such peace independent of intercession (Thy will be done); also that both angels and people respond to this function of God’s will (On earth as it is in heaven).

The fifth tercet shifts the longing for earthly bread that will sustain a living body into the spiritual bread, or manna, that came from heaven in the Old Testament to sustain the Israelite people in their wanderings in the desert, without which the laborer cannot go on (Give us this day our daily bread).

The sixth requests forgiveness of sin while leaving the undeserving parts unworthy of recognition behind, (Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors) and the seventh, requesting deliverance from evil (Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil). Yet they asked it not for themselves, for they have already made the journey to Purgatory and knew that they could only move upward; here instead, the prayer was for the living, a humble request for those still able to make a choice.

After listening to the chanting of this prayer, their slow and labored movements reminded Dante of the heavy and immobilizing weight of nightmares.

As in a dream, when languid sleep seals eyes in our night-time

Rest, we’re aware, in ourselves, of desperately wanting to reach out

Into some purpose or course; but strength, in the midst of our efforts,

Fails us. We feebly slump. Our tongues will not function, our usual

Bodily powers don’t support us. No sound, no words find expression.

Aeneid xii.908-912

Beseeching, thus, good penitence for us

and for themselves, those shades moved on beneath

their weights, like those we sometimes bear in dreams—

each in his own degree of suffering

but all, exhausted, circling the first terrace,

purging themselves of this world’s scoriae.

xi.25-30

The souls were bowed over in humility as they were once lifted in pride in life, each weighed down unequally, as they were unequally proud. Like a ladder of virtue, as the souls in Paradise pray for those in Purgatory, those in Purgatory pray for those still on earth; to complete the cycle, those on earth pray for those in Purgatory to aid their quick movement upward. Those stains carried from the world that are being purged are the P’s that Dante has inscribed upon his forehead.

Virgil bent over and spoke to these souls, asking the way upward, and noting Dante’s eagerness to continue their journey. As a group they answered him, and one voice became distinct as it showed the way

And were I not impeded by the stone

that, since it has subdued my haughty neck,

compels my eyes to look below, then I

should look at this man who is still alive

and nameless, to see if I recognize

him—and to move his pity for my burden.

xi.52-57

The speaker is Omberto Aldobrandesco, son of Guglielmo, who, with the remnants of his earthly pride, assumed that Dante had heard of him; yet he shifted his meaning and humbly ended with, “I do not know if you have heard his name” (60). The nobility of his house and family had filled him with pride in life; he knew now that they had forgotten the common bond that held humanity together—that of the common Mother Earth, or as some say, Eve. He ascribed this error not only to his own downfall, but to the extinction of his family name.

The speaker is Omberto of the great Ghibelline family of the Aldobrandeschi, counts of Santafiora, whose perpetual strife with Siena is mentioned in vi.11. In 1259, the Sienese, exasperated by his arrogance, stormed the stronghold of Campagnatico and killed him.4

Until God has been satisfied, I bear

this burden here among the dead because

I did not bear this load among the living.

xi.70-72

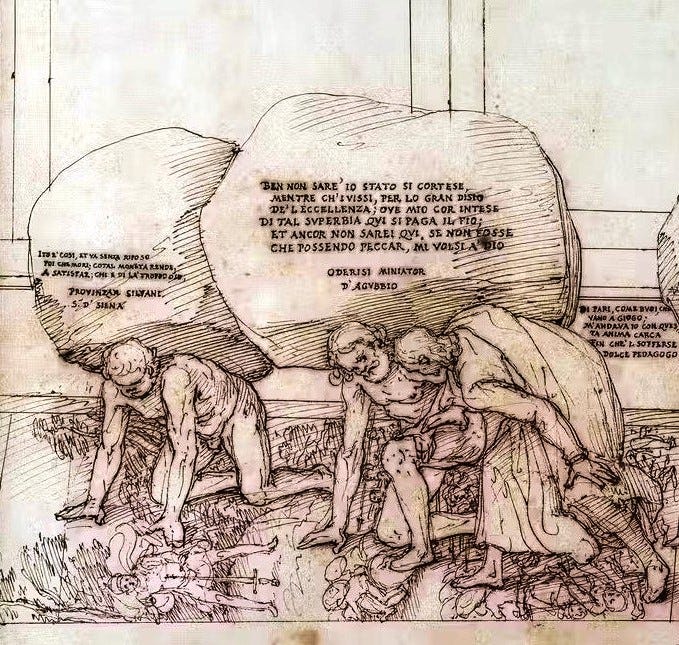

This reminder is of the contrast between those who fulfill their debts on earth—and who are now in Paradise—and those who leave their debt unbalanced. In order to hear Omberto clearly, Dante bent down, as if in his own penitent position of humility. Another soul saw and recognized the poet and called out to him; Dante knew him as well, it was Oderisi of Gubbio. Oderisi was a famous illuminator of manuscripts, whose fame even brought him to work at the Papal Library itself under Boniface VIII. Yet here upon Dante recognizing him, Oderisi praised another instead of himself, one Franco of Bologna. He denounced the earthly fame that bound humanity to their accomplishments.

O empty glory of the powers of humans!

How briefly green endures upon the peak-

unless an age of dullness follows it.

xi.91-93

Fame that lasted longer than an age only arrived when the next generation produced no one to take the reins, becoming an “age of dullness.” He compared the fortunes of Cimabue and Giotto; where once Giovanni Cimabue was the most respected of artists, fickle fame, like fickle fortune, cast him down, and Giotto of Bondone rose up to take his place in the artistic heights. So will the poet Guido Cavalcanti’s5 fame outstrip another Guido, Guido Guinizelli,6 another poet whom Dante admired greatly, after which yet another will come “who will chase both out of the nest” (99); perhaps indicating, as many scholars have concluded, Dante himself.

Worldly renown is nothing other than

a breath of wind that blows now here, now there,

and changes name when it has changed its course.

Before a thousand years have passed—a span

that, for eternity, is less space than

an eyeblink for the slowest sphere in heaven—

would you find greater glory if you left

your flesh when it was old than if your death

had come before your infant words were spent?

xi.100-108

This idea of the span of time in which human fame is but an instant, Dante drew from Boethius:

When you think of your future fame you think you are creating for yourself a kind of immortality. But if you think of the infinite recesses of eternity you have little cause to take pleasure in any continuation of your name. The span of a single second can be compared with ten thousand years, but minute though it may be, it still has a value in proportion because each is a finite measure of time. But ten thousand years, or any multiple of it however great, cannot be compared with unending eternity. For while finite things can be compared with one another, the finite and the infinite can never be compared. So however protracted the life of your fame, when compared with unending eternity it is shown to be not just little, but nothing at all.

Boethius, Consolation of Philosophy II.vii.45-62

So Oderisi continued in his speech on fame, and pointed out a third soul crawling under his weight of stone. This one is Provenzan Salvani, a Ghibelline from Siena, who ruled in a near dictatorship there after being defeated in the battle of Montaperti; again, Oderisi compared that fame to the green grass and the ever changing nature of its colors, transforming from green to brown and back again.

Dante is humbled by this speech, and admitted his own swollen pride—perhaps from the praise he heard of his future poetic glory in line 99. He saw the never ending toil of Salvani, and knowing that he was full of pride until his death, wondered that he was not placed in Ante Purgatory, awaiting his time before being admitted here to the first terrace.

“When he was living in his greatest glory,”

said he, “then of his own free will he set

aside all shame and took his place upon

the Campo of Siena; there, to free

his friend from suffering in Charles’s prison,

humbling himself, he trembled in each vein.

I say no more; I know I speak obscurely;

but soon enough you’ll find your neighbors’ acts

are such that what I say can be explained.

this deed delivered him from those confines.”

xi.133-142

Oderisi told Dante of Salvani’s acts of humility that let him rise to this level of Purgatory at his death; in order to ransom his friend from prison under Charles of Anjou, Salvani took to the streets to humbly beg the money—10,000 gold florins, which exceeded even his own wealth—that he needed to free him; this humble act was sufficient to justify his presence in the first terrace.

Dante will know such wounding of his own fortune in exile; he will become familiar with the necessity to beg for his living, as Oderisi so obscurely hints at in the closing moments of this canto.

💭 Philosophical Exercises

You must find your dream, then the way becomes easy.

~ Herman Hesse

A couple of years ago I read a wonderful book called How to Focus by John Cassian. So, I would like to begin this exploration of Canto XI of Purgatorio by highlighting some of the ideas that I believe can help us understand this part of our journey and help our day-to-day desire to perfect ourselves and manifest our full potential.

John Cassian was a Medieval Christian monk who travelled across different monasteries in search of wisdom; his primary aim was to find practical techniques that one could use to live a better life and to get closer to the Divine.

He wrote that every action, in the view of ancient monastic tradition, involved identifying your telos and skopos. Telos was the higher ideal—what you have to achieve—whilst skopos were the repeatable actions that one had to take in order to reach success. This was an interesting idea, in my opinion, because we see that in Purgatorio, and in further circles and terraces of Purgatory, there are several things that are going to be repeated.

There is going to be prayer. There is going to be what is called suffering, and then the third is going to be meditation.

One could say that in order to reach salvation and absolution, one needs first to pray, which means to identify telos—to know what sin we are purifying ourselves of. Boethius wrote that for doctor to cure a wound, the patient must first reveal it.

In secular terms it means that we need to sit down, look in the mirror and tell ourselves which vices stop us from reaching our full potential. And of course, in the case of this canto, it is pride.

Then, the second step is that one had to suffer, which is represented here by the boulders that are crushing the sinners. The sinners' faces are not visible because of the weight, but we'll explore this a bit more deeply soon.

By suffering, it doesn't mean meaningless suffering. It means that you keep repeating the actions—the skopos—to reach absolution. One example would be if your body is not in perfect shape and you know that you could be healthier; by doing physical exercises that initially cause you pain, and perhaps continuously cause you pain but will give you reward as a result, is an example of this suffering. So it's not meaningless suffering and pain. It does not mean that you must burn your hand meaninglessly by putting it into fire. It is suffering in the way of purification, in the same way as we purify our bodies from excessive weight or from weak muscles, so you purify your soul by conducting regular ‘exercises’. (This is why this section is called “Philosophical Exercises” in the first place.)

Once again, as you can see, I'm bringing in here the relationship between body and soul, because even ancient Greeks conducted their philosophical discussions in what they called Gymnasiums because they believed that one needs to have a healthy body in order to have a healthy mind. So physical exercises for them were connected with mind exercises—spiritual exercises. But once again, I digress. (There is so much to explore, but I don’t want to bore my reader.)

The third thing that they do is, of course, meditation. It is thinking about the world and understanding it. We see this when we meet the very first souls in Purgatory. These people, in contrast to those of Inferno, are speaking about and meditating upon their lives, about their pride. In Inferno, sinners rejected their punishment, they tried to present their crooked way as straight, they showed no remorse.

In Purgatorio we see a contrast, because here, sinners will meditate upon their lives, about the affairs of the world and how things unfold, and about divine justice.

Let’s have a look at the first of them whom we meet here.

To follow the footsteps of John Cassian, I would like to begin by showing the structure of this canto.

It begins with a prayer - a beautiful, moving invocation for mercy and strength to overcome pride and human weakness. The opening lines contain some of the most wonderful passages in the entire Purgatorio7, the verses that say:

Give unto us this day the daily manna

without which he who labors most to move

ahead through this harsh wilderness falls back.

… have particularly touched my heart.

The structure of this canto unfolds in three distinct parts. First, we encounter the prayer itself. Second, we witness souls crushed under the weight of enormous stones on their backs. Third, Dante meets three of these penitent sinners—two directly through conversation, and one indirectly through hearing about him from the others.

The souls here follow the three steps that I have mentioned above: they pray to know their telos, they carry heavy boulders as skopos that will purify them, and then they reflect (meditate) upon their lives.

What strikes me as particularly meaningful is how the three souls Dante encounters here mirrored the three carvings on the rocks we witnessed in the previous canto. Each represents a different manifestation of pride, and each offers a profound lesson about the nature of human vanity. I believe there are practical ‘Philosophical Exercises’ we can take from them.

I. Noble Lineage, Artistic and Political Pride

The first sinner Dante meets is Omberto Aldobrandeschi, who suffers from the pride of noble birth. Dante cannot even see his face because he is pressed so low to the ground by the enormous stone he carries. This physical detail carries deep symbolic meaning: a person whose entire identity rests on aristocratic lineage is so crushed by this burden that he almost ceases to exist as an individual.

Who was Omberto beyond his noble blood? Simply put, nobody. His entire personality, his whole sense of self, consisted of nothing more than his family name. This can be connected to the interpretation from the previous canto—that the stones these sinners carry represent the uncarved selves they could have become. As Michelangelo said, "I saw an angel trapped in the marble, and all I had to do was release it."

The heavy stone Omberto bears is the life he never carved out for himself, the person he never became because he was content to rest on inherited glory.

The second soul is particularly fascinating: Oderisi da Gubbio, an artist condemned for pride in his artistic achievements. Dante converses at length with Oderisi, who speaks humbly about being surpassed by another artist, Franco Bolognese.8 Oderisi reflects on the fleeting nature of earthly fame, noting how Giotto surpassed Cimabue in painting, just as one generation of artists inevitably surpasses the previous.

This conversation reveals an incredibly sophisticated understanding of artistic progress. Both Dante and Oderisi believe that art is inherently progressive—that students must and will surpass their masters.

I believe this is how true artists, including Dante himself, selected their apprentices: they chose those most capable of surpassing them. Robert Hollander's commentary notes that Dante and his contemporaries believed that unless a new Dark Age fell upon them, art would continue to improve because each generation would perfect what came before.

The Dark Ages, by contrast, were defined by the inability to progress or perfect anything. (This is why I believe we live in the modern Dark Ages, and those of you who use Mandelbaum’s translation, please, read the introduction by Eugenio Montale, this theme is explored there. But, once again, I digress!)

The deeper meaning here is much more profound: if you believe you are already perfect, which is exactly what pride tells us, you have nowhere to grow.

Pride whispers: "You are the best. You don't need to do anything more. You are perfect as you are." This is perhaps the worst fate that can befall any human soul, but especially an artist. An artist who believes in their own perfection has no room for improvement, no motivation to grow. They become trapped in their achievements, unable to evolve.

The final soul Dante encounters is Provenzano Salvani, though he learns of him indirectly through the others' conversation. Provenzano was a Ghibelline leader of Siena, condemned for the pride of political power and command. His sin represents pride in rank and authority, the inability to see beyond one's immediate position of power.

He is the inverse of King David’s image, which Dante and Virgil witnessed in the previous canto.

II.

These three souls represent distinct but related forms of pride. I believe that all of us, to one degree or another, experience these, and should be cautious to avoid them in ourselves.

Omberto’s pride embodies static form of pride - he is content with inherited status and unwilling to forge his own identity.

Oderisi represents artistic pride - the belief that one's current achievements represent the pinnacle of possibility. The denial that there is anyone superior to you by not being able to see beauty in the creations of others.

Provenzano exemplifies political pride, a kind of shortsightedness that comes from being intoxicated by temporal worldly power and unable to see beyond immediate authority.

What makes this canto so moving is not just the punishment these souls endure, but their response to it. In Inferno, punishments that the damned had to endure had no goal, they were an end in themselves. The souls here pray, they carry their burdens, they suffer under the weight of those massive stones. They know the telos they aim for and skopos that will help them get there. In their conversations with Dante, they meditate on the world, reflect on their sins, and recognise their mistakes. They acknowledge their crooked ways with humility and understanding.

This transformation, from pride to humility, from self-satisfaction to self-awareness, represents the essential movement of Purgatorio. These souls are not merely being punished; they are being purified, learning to see themselves and their former lives with clarity and wisdom.

This I believe is the true meaning of humility. Humility is not a mere modesty. It is the ability to see that you could be better than you are now.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. Dante’s Pride

Dante bends to see the faces of the souls here. Our pilgrim suffered from this vice himself, he knew that pride drags his own soul down, and as Robert and June Hollander note, Dante expected to share this terrace in the afterlife.

II. Stone Contrapasso

We’ve touched on this before but I want to draw my reader’s attention once again to this contrapasso. We cannot clearly see the faces of these souls, or rather, the extent to which their faces are visible depends on how prideful they were in life.

The message is striking: pride erases. Those consumed by self-absorption begin to vanish, even in life their true identity fades under the weight of their own ego.

III. Glory wilting like the colour of grass

Your glory wears the color of the grass

that comes and goes; the sun that makes it wither

first drew it from the ground, still green and tender

I loved the metaphor of glory wearing the colour of the grass. My reader will remember that in Inferno Dante meets his mentor Brunetto Latini, who is punished for pursuing earthly fame.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

Give unto us this day the daily manna

without which he who labors most to move

ahead through this harsh wilderness falls back.

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on the Purgatorio 220

Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory 154

In answer to the question, would God not love all of his creation equally, Thomas Aquinas says: “Since to love a thing is to will it good, in a twofold way anything may be loved more, or less. In one way on the part of the act of the will itself, which is more or less intense. In this way God does not love some things more than others, because he loves all things by an act of the will that is one, simple, and always the same. In another way on the part of the good itself that a person wills for the beloved. In this way we are said to love that one more than another, for whom we will a greater good, though our will is not more intense. In this way we must needs say that God loves some things more than others.

Summa Theologica I.q.20.a.3

Sayers 155

Whose father, Cavalcante de’ Cavalcanti, we met in Inferno X.63

Whom we will meet in Purgatorio xxvi.97-99

In my humble opinion of course!

I attempted to find some of the illustrations by Franco, but his bloody surname Bolognese brought me sauce recipes instead of medieval illuminations.

I found this at Sotheby's

https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2015/master-paintings-part-i-n09302/lot.12.html

>Longhi further ventured that this artist, whom he referred to as Maestro della Bibbia Parigina (Master of the Paris Bible, or Master of the Bible Lat. 18 for our purposes), may be identifiable as Franco Bolognese, a miniaturist in service to the pope. In his epic poem, The Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri describes meeting Franco in Purgatory, though amusingly the artist was still very much alive at the time of Dante’s writing.

>In 1951, however, Pietro Toesca proposed an alternative identification of the Master of the Bible Lat. 18, considering him to be the Bolognese painter Jacopino da Reggio

It is slightly better than a recipe for bolognese sauce, but may not be a Bolognese per se. If one has a spare 1.8-2.5M it may look nice on one's kitchen wall yet alas bidding has closed.

Thanks Vashik for another fantastic article.

Dante’s expansion of The Lord’s Prayer is sublime!