A Map to the Labyrinths of Our Psyche

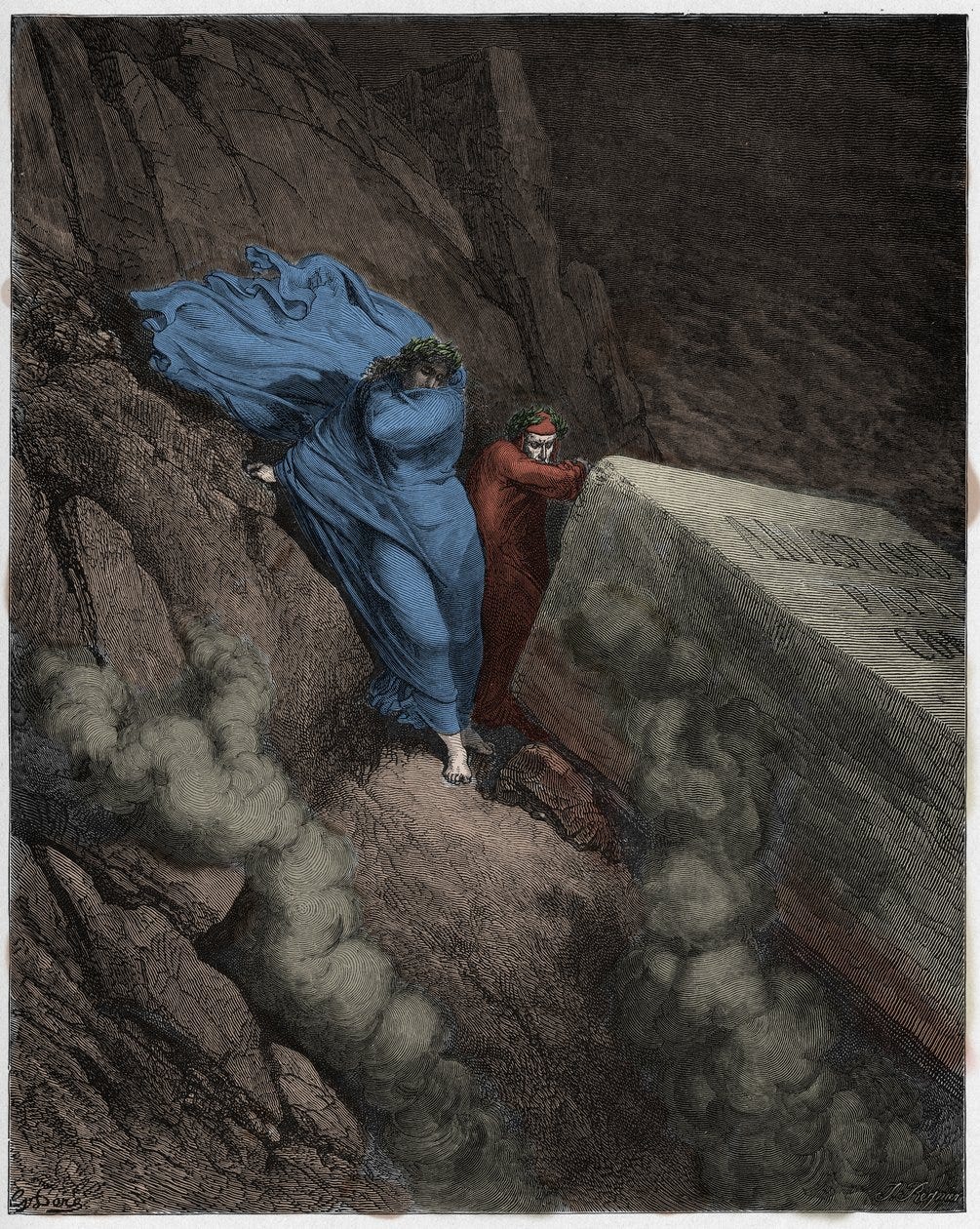

(Inferno, Canto XI): Virgil and Dante discuss the architecture of lower Hell

“Bad people...are in conflict with themselves; they desire one thing and will another, like the incontinent who choose harmful pleasures instead of what they themselves believe to be good.”

~ Aristotle, Nichomachean Ethics

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Eleventh Canto we find the Pope Anastasius and the architecture of lower Hell. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Upper banks of the Seventh Circle of Violence - Dante and Virgil break to adjust to the atmosphere - The tomb of Pope Anastasius - Virgil describes the coming circles - The three subdivisions of the Seventh Circle of Violence - The Eighth Circle of Deceit, or Simple Fraud - The Ninth Circle of Treachery, or Complex Fraud

Canto XI: Summary

As Dante and Virgil walk around the edge of the Seventh Circle, looking down over the embankment of broken rock, they had to stop and adjust to the atmosphere of the next layer of punishment, so strong was the stench rising from it.

Dante reads an inscription on one of the lids of the tombs, “I hold Pope Anastasius, / enticed to leave the true path by Photinus” (XI.8-9). This tomb holds Pope Anastasius II, who was involved in the Acacian Heresy between the Eastern and Western Christian churches. Photinus was an Eastern Christian deacon of Thessalonica, to whom Pope Anastasius reportedly gave communion in an attempt to show reconciliation between the two sides of the rift, but which led to condemnation. The Acacian Heresy revolved around either recognizing the divine birth of Christ or considering him to have been of a purely human birth.

Dante accepts Virgil’s suggestion of a pause, and suggests that they should make the time productive. Thus begins a memorable speech describing the layout and architecture of the realms of Hell that are before them, the subdivisions within each circle expressing the nuance of each offense in the greater themes of Violence, Deceit, and Treachery. Virgil speaks:

Of every malice that earns hate in Heaven,

injustice is the end; and each such end

by force or fraud brings harm to other men

XI.22-24

This Seventh Circle - where they are currently resting, about to descend - holds the sins of Violence, those of the lion. It is further subdivided into three realms, or rings, indicating three kinds of Violence. These three rings are based on a blend of ideas from Aristotle and Cicero,1 classical ethical principles.

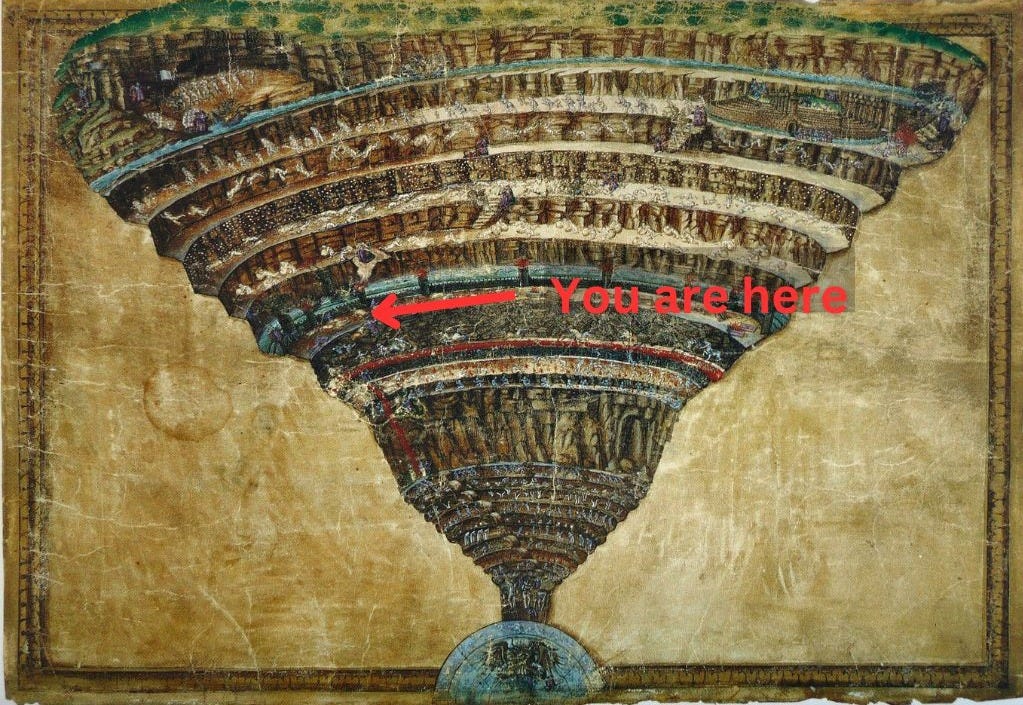

The bigger structure of the rest of Hell that Virgil describes in this Canto are the Seventh Circle of Violence with its three subdivisions, the Eighth Circle of Fraud of Deceit, which moves to the sins of the she-wolf with its ten subdivisions, and the Ninth Circle of the Fraud of Treachery with four subdivisions, ending in the very deepest frozen pit of Hell.

With that bigger framework in mind, let us examine the Seventh Circle, and the distinction of the three rings that we find there.

The “force against three persons” (XI.29) refers to the three directions to which these offenses are directed in Circle VII of Violence; “to God and to one’s self and to one’s neighbor” (XI.31). The violence can be directed to each of these three, or toward what belongs to them. These are taken directly from Thomas Aquinas: “Every sin is against either God, or one’s neighbor, or oneself.”2 Note the subtleties of Dante’s interpretations of the expression of violence in its range from murder to blasphemy.

The first, closest subdivision of Circle VII is of physical violence and destruction; murder, theft, and extortion. It is toward people as well as property, since “property is regarded, in accordance with Roman law, as an extension of the personality.”3

The second subdivision of Circle VII is violence against the self, so suicides are found here; “whoever would deny himself your world” (XI.43) by removing themselves from it. The profligates who waste resources are here also, even emotional resources, seen in the reference to excess sadness; those who “wasted their own substance in the extreme.”4

The third subdivision of Circle VII is violence against God and nature, “one’s heart denying and blaspheming Him / and scorning nature and the good in her” (XI.47-48). Here is blasphemy, sodomy and usury. While humanity cannot directly harm God, the willful attempt to do so is no less sinful.5 Here is it crucial to see the distinctions of these sins as based on Dante’s worldview of medieval Christianity.

Just as the ordering of right reason proceeds from man, so the order of nature is from God Himself: wherefore in sins contrary to nature, whereby the very order of nature is violated, an injury is done to God, the Author of nature6

We will see Circle VII in detail in the upcoming Cantos. Now looking down to the rest of their Inferno journey, Virgil also describes the furthest reaches of Circles VIII and IX.

Circle VIII is known as Deceit or Simple Fraud, one of the two realms of Malice, and here begins the sins of the wolf, as well as lower hell. This circle is filled with those who betray others in myriad ways, in ten subdivisions:

Nestled within the second7 circle are:

hypocrisy and flattery, sorcerers,

and falsifiers, simony, and theft,

and barrators and panders and like trash.

XI.57-60

Circle IX houses Treachery, those who did not only commit fraud by deceiving others, but did so with people that they held in the deepest trust, making the deceit even worse. This is Fraud Complex, due to that breaking of trust, and is the very bottom of Hell.

Now that Virgil has laid out what is to come before them, Dante is trying to understand why certain sins are held in different areas and levels of Hell, he wonders why they are not all in the flaming city of Dis? Why the distinction of punishment?

Virgil scolds Dante, “why does your reason wander / so far from its accustomed course?” (XI.76-77). This points to that all-important medieval sense of order, that we are to be as orderly as the planets in the structure of our minds and bodies and souls.

He reminds Dante of the words of Aristotle’s Ethics concerning the types of error that are the very areas that Dante has ordered his hell after: “incontinence and malice and mad bestiality” (XI.81-82).

So, those sins that we saw in the beginning, the first circles of incontinence through greed, lust and avarice, are the least offensive to God, and if we look at the severity of the punishment, we will see they are not so dire as what we shall shortly encounter. There was no malice in these sins.

If you consider carefully this judgment

and call to mind the souls of upper Hell,

who bear their penalties outside the city,

you’ll see why they have been set off from these

unrighteous ones, and why, when heaven’s vengeance

hammers at them, it carries lesser anger

XI.85-90

After the clarity that Virgil brings in helping Dante understand these distinctions, he asks for one more insight. He asks Virgil to explain why usury is included in the third subdivision of Circle VII of violence toward God.

If philosophy is based on the unfolding of nature - an external expression of the divine intellect - then to let ourselves also unfold as nature does is living in harmony. Aristotle states that “art imitates nature”8 meaning that our art should then also strive to follow this divine art, so that what we create is like the offspring of God:

That when it can, your art would follow nature

just as a pupil imitates his master;

so that your art is almost God’s grandchild

XI.103-105

Humanity makes their living by the blending of this art and nature to produce the work of their hands from it, thereby sustaining themselves. Virgil references Genesis in which Adam and Eve are cursed to work the ground: “in toil shall you eat of it all the days of your life” and “In the sweat of your brow you shall eat bread.”9

Therefore to understand the placement of usury, with it’s offspring of interest, is to look at it as something that was not worked for through that blend of art and nature, and therefore is a defilement of the purpose of work as God deemed it.

Thus they spent their time by the tomb of Pope Anastasius, and accustomed to the air of the realm, they continued on, under the sign of Pisces, the fish.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

Before beginning, plan carefully.

~ Cicero

In one version of the story of Saint Paul's journey into Hell, the Archangel Michael tells him to pause at one moment in order to accustom himself to the stench that rises from the abyss. Saint Paul does so, stuffing a fold of his mantle against his nostrils. Dante adopts this detail to provide an opportunity for Virgil to describe to Dante the layout of Hell.

I. Mapping Hell

Our mind is a labyrinth and if enter without a clear map, we may never find our way out. The sins that are rooted in intellect are more cunning in their nature. Our mind can go through extraordinary lengths of self-deception. To reach new depths, traverse uncharted paths, and withstand relentless demons, Dante and Virgil must first map their journey, so they may stay on the right course.

Philosophical works such as Pierre Hadot’s Philosophy as a Way of Life and Martha Nussbaum’s The Therapy of Desire explore how one can attain a ‘flourishing life’ through Stoic, Epicurean, and Skeptic traditions. Both emphasise the necessity of mapping one’s path—knowing which port you are sailing toward (to use Seneca’s words)—before embarking on the journey.

II. Cicero and Aristotle

Dante structures the lower depths of Hell upon the principles of Aristotle’s Ethics and Cicero’s On Duties. In Aristotle, he had found wrongdoing divided into three categories: weakness of will, brutishness and malice. Cicero recognised only two: violence and fraud. Dante combines the two systems, adding to that of Cicero the category of incontinence (weakness of will), distinguished by Aristotle from his sins that involve the deliberate use of the will.

We will have plenty of space to explore the circles and sins that await us in the coming cantos of the Inferno. So, in this post, I will not delve deeply into the nature of violence, its significance, or why fraud—an inherently Ciceronian notion—is considered among the worst sins. Instead, I would like to briefly focus on usury, as Dante himself does here.

III. Usury and Money Lending

Go back a little to that point,” I said,

“where you told me that usury offends

divine goodness; unravel now that knot.”

It is said that a great Florentine banker, who lived after Dante yet had read The Divine Comedy, feared he would find himself among the usurers in Inferno after his death. That banker was Lorenzo de’ Medici, renowned as the patron of Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and many other geniuses.

One might argue that his patronage of the arts was merely another instrument of power, yet I believe a deeper motivation was at play. After all, if art were solely a tool of influence, as some claim, why do the wealthy of our time not nurture and cultivate artists of Michelangelo’s caliber today?

As Kenneth Clark notes in Civilisation, Lorenzo was fully aware that his wealth came from money itself—his fortune was built on usury, the most reviled practice of his time. But why was usury—profiting from money alone—so fiercely condemned by Christianity?

that when it can, your art would follow nature,

just as a pupil imitates his master;

so that your art is almost God’s grandchild.

Every line in The Divine Comedy carries meaning, but this one struck me in a peculiar way. There is a Divine Intelligence, and we are its offspring. What we create—our art (arte, meaning craft)—is, as Virgil puts it, ‘almost God’s grandchild.’

The creation of money for its own sake adds nothing to the world—it does not bring forth Michelangelo’s Pietà or da Vinci’s Madonna of the Rocks, nor does it give us Botticelli’s Primavera or Raphael’s The Transfiguration.

Lorenzo di Medici knew that his activity did not correspond to the Divine Ways. Weaving strands of Aristotle and St. Thomas, Virgil demonstrates that nature takes her course from the divine mind, and that “art” then follows nature. Humankind, fallen into sin, as he recorded in Genesis, must earn its bread in the sweat of its brow, precisely by following the rules of nature and whatever craft it practices. And for this reason usurers are understood as sinning against nature, God's child, and her child, “art” (in the sense of “craft”), thus the grandchild of God and all the more vulnerable to human transgression.10

IV. Final Thoughts

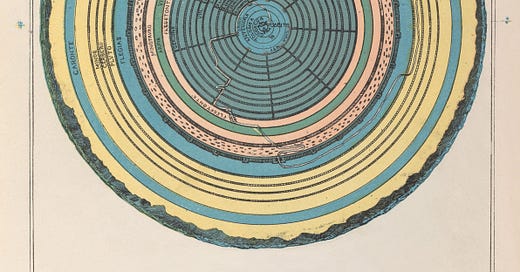

At the start of this section I included the map of Inferno made by Michelangelo Caetani. If you pay close attention you will see that there is a white path that goes all the way from the shadowed forest and to the deepest depths of Hell.

We have to remind ourselves that Dante’s only map through this journey was Virgil, his reason. He did not have Botticelli’s map at hand, or that of Caetani.

In this canto Dante and his readers are allowed to catch our breaths. We have been through so much already together. We have escaped the shadowed forest and met many beasts and sinners on our way. This canto allows us to get used to the stench that is here but also reminds us that certain places must be entered with a map at hand.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Themes 🖼️ :

One short remark on Aristotle and Cicero

Dante’s poem is an encyclopedia—encompassing mythology, etymology, theology, philosophy, and even science. What fascinates me is how nearly everything I read and explore, whether explicitly or subtly, seems to connect back to Dante’s work.

Months before this read-along, I was immersed in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. I summarize each chapter of almost every book I read, gathering actionable ways to improve my life, and I did the same with Aristotle. It is an extraordinary work of philosophy—one of the most significant I have read so far. Yet since we began this journey through Inferno, I have been struck by how deeply Aristotle’s ideas permeate Dante’s writing.

The same holds true for Cicero. In a philosophy group I’m part of, we recently discussed Cicero’s reflections on the nature of friendship, and once again, I see those very ideas woven into Dante’s text.

This, which I initially intended to be as a brief remark, has grown far longer than expected. But what I truly wish to say is this: Dante’s influence is everywhere. His signature is not only imprinted on the literature and philosophy that preceded him but on the works of art and thought that followed.

What differentiates us from animals?

There is much we share with animals, but one gift sets us apart—a gift bestowed upon us by God: the gift of intellect. When we turn our intelligence, our reason, toward harmful ends, we do not merely err—we rebel against the divine order itself.

Several centuries after Dante, the Portuguese-Dutch philosopher Benedict Spinoza secularised this idea, asserting that true flourishing is achieved by aligning the mind with the workings of Nature.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

I copied two passages from this canto into my journal. The first is Virgil’s reflection on the usurers; the second is a brief but profound sentence below. I have highlighted the words that I will carry as reminders throughout my life in bold.

“O sun that heals all sight that is perplexed,

when I ask you, your answer so contents

that doubting pleases me as much as knowing.”

‘… that doubting pleases me as much as knowing’! How beautiful is that!

Characters:

- Pope Anastasius II - Bishop of Rome from 496-498, he attempted to unify the division between the Eastern church based in Constantinople and the Western church based in Rome; this was the Acacian schism. Photinus was of the Eastern church, and Anastasius II giving him communion was in effect blessing someone on the other side of the conflict.

- Photinus - Deacon of Thessalonica, who, according to Dante’s sources, was given communion by Pope Anastasius II as a token of goodwill to try and heal the Acadian schism then taking place between the Eastern and Western Roman church.

- Sodom - In Genesis 18-19 of the Old Testament, Abraham learns that the City of Sodom is to be destroyed because there are no righteous ones who live there; it was known as a center of vice. Abraham begs the Lord to spare the city if righteous men can be found there; his brother Lot lives in Sodom. Lot and his family are spared, yet his wife, like Orpheus, could not resist looking back, and was turned into a pillar of salt.

- Cahors - A city in southern France that was known for the practice of usury, or moneylending with interest. Bocaccio says about Cahors: “Cahors is a city in Provence…so completely given to loans and usury that there is no one in the city, man or woman, old or young, small or great, who is not well versed in those matters…Their wretched practice is so widespread, especially among us, that the phrase “he is from Cahors” means that the person is a usurer.”11

Aristotle divided error into three sections: incontinence, bestiality and malice or vice. Cicero also divided error into subsections of violence and fraud, therefore Dante mingles their categories into his own. Sayers Hell 139

Summa Theologica II.II, q. 118, a. I, obj. 2

Sayers Hell 140

Singleton, Inferno Commentary 169

The role of nature in the medieval mind as the handmaiden of Divinity is expressed so: “Nature’s role is thus one of containment and coordination rather than creation…and aligns the celestial principle with the earthly in the constitution of man” (Winthrop Wetherbee, Cosmographia of Bernardus Silvestrus 35).

Summa Theologica II.II, q. 154, a. 12, ad 1

In saying the “second” circle, Virgil is referring to the second of the three circles he is explaining; so it is actually referring to Circle VIII.

Physics ii.2.194a

Genesis 3:17, 19

From Hollander’s note to lines 97-111, I thought this was articulated well and was worth the full quotation. You can find them on pages 215.

Singleton 172

That you bring all this knowledge to bear on our subject, and that you do so twice a week to a deadline, with such generosity, is a constant marvel. Thank you so much.

Sinclair says this is the most prosaic of the cantos in the Inferno, “being little more than a verbal diagram.”

But as you note, that “verbal diagram” is an important point of reflection since it affords the opportunity to acquire an overarching view of the logic and structure of Hell.

For me, Dante’s “orientation” of Aristotle and Cicero’s conceptions brought to mind the famous strategist Karl von Clausewitz’s description of war’s “logic and grammar” in his treatise “Vom Kriege” (On War). One would think war and Hell are unbounded extremes, but quite the opposite is true — both are characterized by their own “logic and grammar.” Clausewitz saw that while war has “its [own] particular rules and its basic principles,” it does not have its own logic; that is provided by policy (the set of rules [imperatives, principles and customs] that govern reasoning in the use of war as an instrument of policy). War does have its own grammar (the collection of rules and procedures employed by a military force to achieve the ends established by policy).

One could similarly argue that the“logic” Dante applies to Hell is not Hell’s to make — it comes from the ultimate policy-maker — in the form of divine justice. Dante’s “grammar” derives from the application of Aristotle and Cicero’s characterization, hierarchy, and classification of sin.

Speaking of “verbal diagrams,” both Dante and Clausewitz reflect mastery of linguistics and how to express their unique view of their respective worlds, which is why one line in Canto XI struck me as extraordinarily interesting: “…fraud is man’s peculiar vice.”

My first reaction was “Of course it’s peculiar to man, animals can’t sin!” After all, the concept of good and evil does not adhere to animals; they lack rational souls and free will; they cannot form intent; they are not capable of moral corruption, therefore they cannot be held morally responsible. Sin requires a conscious and deliberate turning away from God — since animals are governed by instinct, they do not possess the capacity to “turn away.” What is “peculiar” about fraud then, I would argue, is, as you note, what Aristotle said was the essence of the human being: “zoon logon echon” — the human is the animal with language. By it, he described man’s ability to use logos (reason/speech) to think, deliberate, communicate, and engage in moral decision-making. Language and reason, ill-employed, can deliberately distort “logic and grammar” in order to commit fraud. Very peculiar to man, indeed.