Dante Plays Zara: Is Fate Just the Roll of a Die?

(Purgatorio, Canto VI): Violent Ends, Last Prayers, A Country Divided

Too much thinking and not living restricts us, too much plunging in life without thinking makes us brutes…one should find balance between these two.

~ Goethe

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Sixth Canto of the Purgatorio, we hear Dante’s political invective against Italy. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Dante is beset by requests for prayer - More victims of death by violence - Dante asks Virgil the nature of the power of prayer and its effectiveness for change - They meet the poet Sordello - Dante’s digression on Italy, the Church, the Emperor, God, and Florence.

Canto VI Summary:

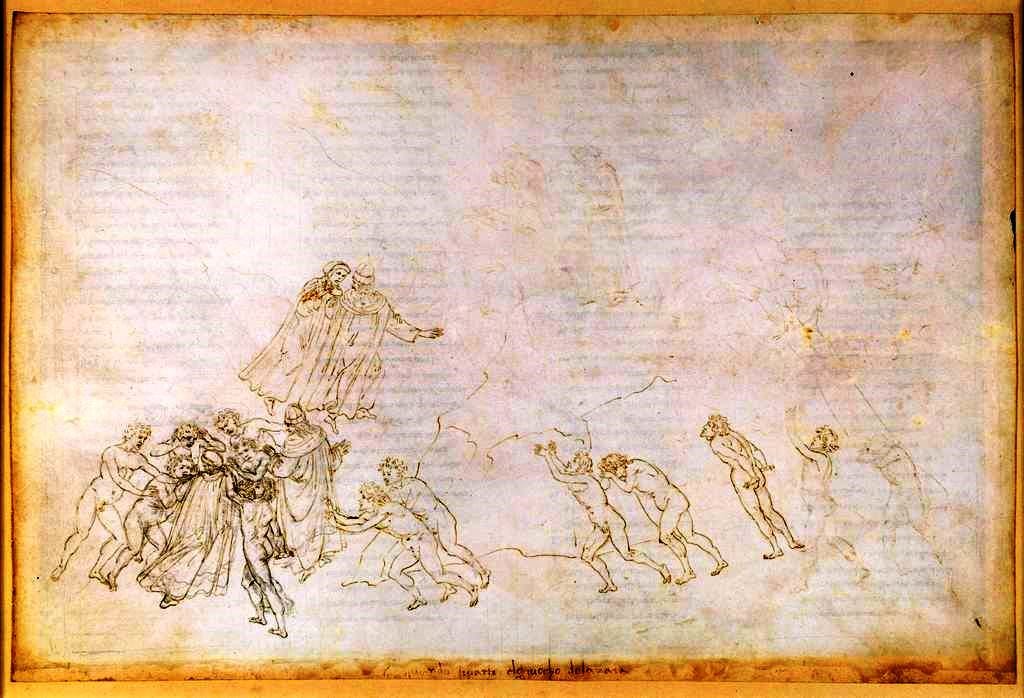

Still on the terrace of the Unshriven, and having just left the three figures who died violently, Jacopo, Buonconte, and La Pia, Dante explores through extended metaphor his position of one who has won at a game of dice — or zara — surrounded by a crush of penitents looking for favor.

We observe that, when people are playing games of chance such as with dice, there will be a group standing to watch the game, and when one of the players wins, they will ask for a share of his profits and the players will always give it to them.1

He found himself promising to deliver their requests — for prayers in the world of the living — and just as the winner at dice will give small tokens of his winnings as a celebration to those who celebrate with him, after which they go on their way, so did Dante find himself handing out these promises to the souls crowding round him. He recognized so many in that crowd who had died violently.

He knew of Benincasa da Laterina, the Aretine, a judge who had been murdered in revenge by Ghino di Tacco, a notorious highwayman and the brother of one whom Benincasa had found guilty in court and sentenced to death —

He knew of Guccio de’ Tarlati, the one who drowned in the Arno river, a Ghibelline who died in pursuit of Guelph exiles —

He knew of the one with hands outstretched, Federigo Novello, the son of a count who was killed by Guelphs —

He knew of the Pisan, Gano degli Scornigiani, who was killed by the followers of Count Ugolino, and whose death inspired his father Marzucco to become a Franciscan Friar, choosing a dedicated life to God over revenge for his sons death —

He knew of Count Orso of the Alberi family who was murdered by his cousin —

And finally, of Pier de la Brosse, chamberlain of king Philip III of France, who was executed after implying that Philip’s wife, Marie of Brabant, conspired to poison the Dauphin Louis so that her own son could be king, becoming Philip the Fair. Dante singles out Marie, who was still living at the writing of his poem, warning that she “watch her ways — or end among a sadder flock” (23-24); her crimes could cast her into Inferno.

These six males, all of whom died violently between 1278 and 1297, are presented as a sort of coda to the three developed figures who bring the preceding canto to its end (Jacopo, Buonconte, Pia), leaving us with the impression of the potentially more extensive narratives that might have accompanied their names, with still more resultant pathos.2

Once Dante freed himself from the shades seeking his attention, he called attention to a theory proposed by Virgil concerning the ability of the power of prayer to change circumstances in decrees set by the gods, noting a discrepancy between the rule of antiquity and the rule of medieval Christianity. In Purgatory, the prayers of the living are taken to have a decided effect on the movement on the souls travelling within:

I started: “O my light, it seems to me

that in one passage you deny expressly

that prayer can bend the rule of Heaven, yet

these people pray precisely for that end.

Is their hope, therefore, only emptiness,

or have I not read clearly what you said?”

vi.28-33

Dante’s reference for this idea came from Aeneas’ journey to the underworld in Virgil’s Aeneid. Guided by the Sibyl, they encounter Aeneas’ shipmate Palinurus, who had been washed out to sea on their journey and who subsequently was killed by those he met when he washed ashore; his body had been left unburied. Now in the underworld, he was not able to cross the Cocytus in Charon’s boat, and had to wait upon the far shore until he was either given proper burial, or until 100 years had passed; no imploring on his part could change that fact. The Sibyl tells him:

What brings this terrible urge that sweeps over you now, Palinurus?

You, an unburied soul, plan to gaze upon Stygian waters,

Pitiless Furies’ streams? You’ll cross to those banks uninvited?

Cease to hope fate, once spoken by gods, can be altered by prayer!

Grasp and remember these words to console you in bitter misfortune.

Aeneid vi.373-377

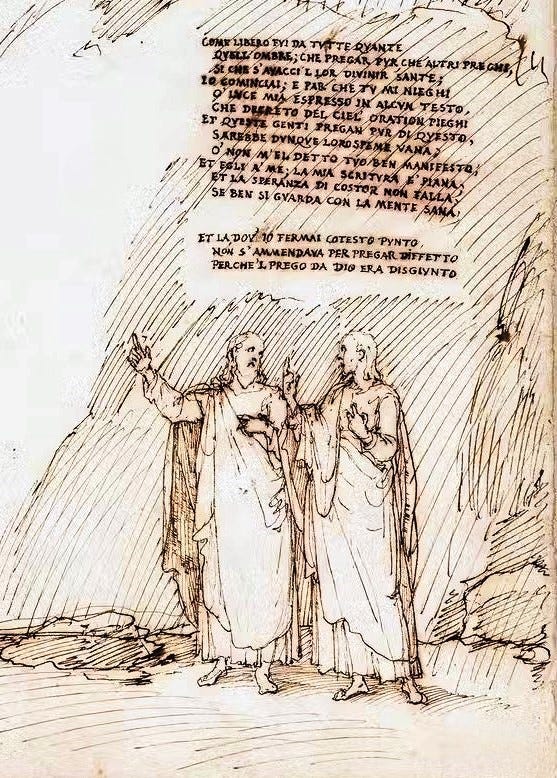

Virgil then explains the difference in the reception of prayer from his age to Dante’s:

And he to me: “My text is plain enough,

and yet their hope is not delusive if

one scrutinizes it with sober wit;

the peak of justice is not lowered when

the fire of love accomplishes in one

instant the expiation owed by all

who dwell here; for where I asserted this —

that prayers could not mend their fault — I spoke

of prayers without a passageway to God.

vi.34-42

Living before the time of Christ, Virgil explains, Palinurus would not have benefitted from the divine grace that brought a penitent’s prayer to God; their relationship with the gods of antiquity was of a different kind. There, the judgment was a final call. Theologically, after Christ then, the prayers of others, sent with enough burning ardor, could fulfill the debt of the one in Purgatory, letting them move forward. The debt in this case did not have to be fulfilled by the penitent, but could be helped along by others. Justice is still served, but paid from a different source. While this may shorten their time waiting to enter Purgatory proper, they still must work through the cleansing of Purgatory itself, though that also may be helped along by the prayers of the living.

As the concept of Ante Purgatory is Dante’s invention, this theological wrangling is merely poetic; yet it serves a greater purpose, in that Dante is validating Virgil’s authority through the reconciling of the two very different doctrines.

But in a quandary so deep, do not

conclude with me, but wait for word that she,

the light between your mind and truth, will speak -

lest you misunderstand, the she I mean

is Beatrice; upon this mountain’s peak,

there you shall see her smiling joyously.

vi.43-48

Reason can only take Dante so far in this kind of understanding; rather, Beatrice will have an authority that Virgil does not, to enlighten Dante in all of these questions. Just the very mention of her name shifts Dante’s sense of movement from simply a journey up Mount Purgatory — if we can even call it simple — into a journey to Beatrice; he is invigorated and energized, eager to move quickly, as they have already fallen into shadow as the day progresses, with the sun behind the mountain.

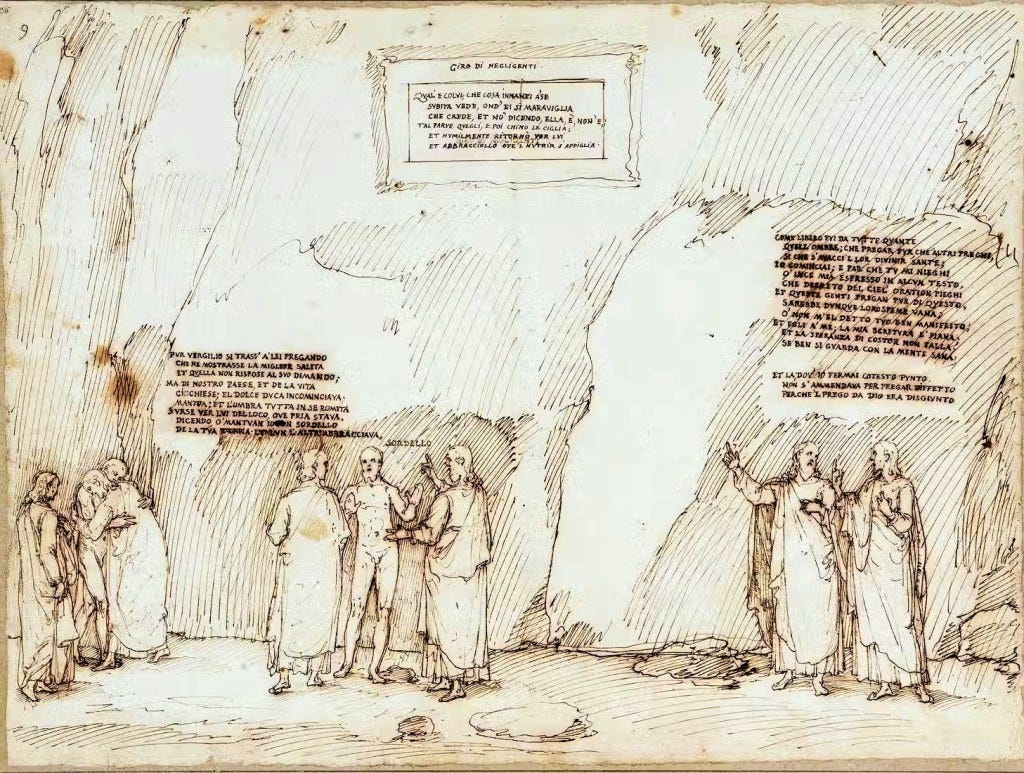

Virgil sees a soul nearby, to whom they will ask the way:

We came to him. O Lombard soul, what pride

and what disdain were in your stance! Your eyes

moved with such dignity, such gravity!

He said no thing to us but let us pass,

his eyes intent upon us only as

a lion watches when it is at rest.

vi. 61-66

This soul, from the north of Italy in the Lombard Kingdom, poet and troubadour, is the highly respected Sordello of Goito. His stance and lion-like gaze make of him a distinguished character.

In our language, we use the words altiero (lofty) and disdegnoso (disdainful) of the man whose excellence of spirit is such that he completely ignores vile things and will not stoop to them. Such a man shows fastidiousness that is generous and without taint. But if a man is scornful not out of magnanimity but out of arrogance we call him not altiero, but superbo (haughty).3

Sordello the troubadour was born at Goito near Mantua about 1200. After wandering from court to court in Italy, Provence, Spain, Poitou, Portugal, and various parts of France, he attached himself to Charles of Anjou and spent most of his later life in Provence. All record of him is lost after 1269, but there is a tradition that he died a violent death. Later in the Comedy we are reminded of Sordello’s intrigue with Cunizza (wife to Ricciardo di San Bonifazio and sister to Ezzelino III da Romano) whom Dante places in the Heaven of Venus; the repentance of this pair of lovers seems to be of Dante’s own imagining.4

Virgil approached to ask this soul, as yet unnamed, the way forward, but he ignored the question and instead posed one of his own, asking who these two were, and where they were from. As they were in the shadow of the mountain cast by the sun being behind the edifice, Sordello did not seem to realize that Dante was a living man. Virgil began his response with what could have been taken as a familiar saying, his epitaph, which began with Mantua me genuit…

Sordello’s disdain immediately shifted into joy as he recognized a fellow Mantuan in Virgil, and the two shades embraced — note the contrast in Dante attempting to embrace Casello ending in failure — an embrace that seems to trigger the ensuing digression and break in the narrative story of the poem, to expound upon the lack of unity and corruption in Italy.

This aside is one among a larger pattern of discourses on politics, for each cantica, or section of the poem, has such an aside contained within the the sixth canto: first, the nature of the city of Florence in Inferno, here on Italy herself in Purgatorio, and later on that of the entire Empire in Paradiso.

While even Dante may call this selection a digression, its greater purpose is part of the purpose of his poem. Within this diatribe, he speaks of the corruption within Italy, the Catholic Church and her priests and leaders, the uncrowned Emperor Albert I, even reaching to questioning God, and finally Dante’s city of Florence.

Italy, without a true steersman in a strong emperor, is headed for destruction just as a ship without navigation, and the glory of Rome is as degraded as a noble beauty condemned to a brothel. Where Virgil and Sordello could embrace by virtue of sharing a homeland, the same could no longer be said for any other of Italy’s citizens; in contrast, they are attacking and killing each other with a complete loss of unity. There is no place in any region that knows peace. Even with the code of Justinian having codified Roman Law, there is no one to put it into proper use or perspective.

Then there is the church, who instead of acting in their circle of spiritual guidance for the people, have taken the reigns of politics, and blending sacred with temporal power, have distorted the true purpose of both; society has grown into a beast turned vicious with no direction.

Nor does the Emperor Albert help guide matters; the corruption of the Habsburg house has contributed to the downfall of Italy. With sarcastic wit, Dante cries out to Albert to come and see the downfall that he has helped to bring about; the civil strife between the leading families of the Guelphs and Ghibellines, the unrest among the nobility, Rome, abandoned and in mourning, citizens who have lost any sense of love and unity with their fellow countrymen.

He begs that God in Heaven look kindly upon the suffering, and wonders if they are but pawns trapped in the movement of a greater game. Italy is beset by tyranny, Florence most of all, whose corruption is so deep that while positions are taken by force, they consider themselves full of wisdom and peace; this is but a farce. Their laws passed in corruption hardly last weeks, unlike laws of old, of the city states of Athens and Sparta whose justice is still spoken of in that day. Florence is beset with shifting loyalties and erring corruption, perhaps looking rich and elegant on the outside, but instead is fevered within, tossing and turning, with no escape from the pain of decay.

This is Dante’s lament.

Woe unto that audacious soul of mine, which hoped that had she forsaken thee, she should have had some better thing! Turned she hath, and turned again, upon back, sides, and belly, yet found all places to be hard; and that thou art her rest only.

St Augustine, Confessions VI.16

💭 Philosophical Exercises

We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have still not been touched at all. Of course there is then no question left, and just this is the answer.

~ Wittgenstein

When dicing’s done and players separate,

the loser’s left alone, disconsolate—

rehearsing what he’d thrown, he sadly learns;all of the crowd surrounds the one who won—

one goes in front, and one tugs at his back,

and at his side one asks to be remembered;he does not halt but listens to them all;

and when he gives them something, they desist;

and so he can fend off the pressing throng.

You cannot control the dice. Every child knows this. No matter how carefully you plan, no matter how incessantly you hope to roll the number you need to win, the dice will fall as they will. Their outcome is never at your command.

Life must be lived forward, but it can only be understood backward. The game of dice is no different: you throw, you witness the outcome, and only then can you reflect on what has occurred.

The question, of course, is how to interpret the result. If you won, why? If you lost—could you have done anything differently?

I. How to Play Dice Like Dante - (Destiny and Calculation)

In Dante’s time, dice games were among the most popular forms of gambling. The game was called zara, a name that originates from Arabic. Interestingly, while reading Dante for the first time, I noticed a striking connection: the Armenian word for dice is zar (plural zarer)—a link that caught my attention.

When my friends and I used to play zara, we used two dice, and the highest roll would win. But in Dante’s day, the game was played differently.

Medieval players used three dice, and although high numbers mattered, something else mattered even more: probability. For instance, rolling three 1s would automatically win the game even against a higher total because of how rare and statistically improbable such a roll was. Another highly improbable and automatic win was a roll of 6+6+6 — the highest possible total and just as rare as triple ones.

Before rolling, players had to announce their expected result. If you felt lucky, you might declare “triple ones” and hope for a miraculous win. But if you wanted to play it safe, you’d choose 10 or 11 — numbers with the highest probability of success, thanks to the many possible combinations that could yield them.

Our life resembles more a game of dice than that of chess. In chess, fortune plays almost no role everything depends on logic, strategy, and precise calculation. In zara, however, it is the opposite: calculation is minimal, and fortune reigns supreme.

We do not choose the parents we are born to, it’s a roll of the dice. We do not choose the place on earth where we first open our eyes, that too is a roll of the dice. We do not choose the state of our health at birth, once again, a roll of the dice. It seems that everything most essential, most decisive, is left to chance - like the cast of dice.

The problem is — what do we mean by chance? What do we mean by randomness? When we say that something happened randomly in a given situation, what do we exactly mean?

The sun does not wander aimlessly across the sky, nor do the winds blow without cause or pattern. So why do we imagine that some events unfold by mere chance, as if coins that we can flip into the air?

II. If we cannot choose the most essential aspects of our lives, then what can we choose?

I started: “O my light, it seems to me

that in one passage you deny expressly

that prayer can bend the rule of Heaven, yetthese people pray precisely for that end.

Is their hope, therefore, only emptiness,

or have I not read clearly what you said?”(lines 28-33)

This is precisely what Dante asks his guide: if we cannot choose the most essential aspects of our lives, then what power do we truly have? If everything is already decided, do our choices, our actions, our prayers mean anything at all? If, no matter how hard you try to predict the dice, the outcome unfolds without regard for your will, then what is the point of trying at all?

Virgil answers the way our reason would, he refers to his poem Aeneid, to the lines:

‘desine fata deum flecti sperare precando’

(cease hoping that decrees of the gods may be turned aside by prayer)

~ from Aeneid, Book VI

If Dante and Virgil were to play dice, Virgil would interpret the outcome, whether victory or loss, as fate. It was meant to be. What we might call randomness, Virgil would see as a fixed path, unchangeable and beyond human control. He could have done nothing differently.

As Erich Auerbach notes in his study of Dante, the ancients believed that a man’s character is his fate; one’s destiny follows inevitably from one’s nature. But for Dante and for the Christian worldview, this is profoundly different: fate can be altered by transforming one’s character.

Indeed, this is at the heart of Dante’s masterpiece. Dante’s pilgrimage is a journey of inner transformation, a conscious attempt to alter his destiny by reshaping his soul. And in doing so, he begins to uncover the deeper forces that lie behind what we call ‘chance’ forces that, in the end, are anything but random. This brings us to the most fascinating part, the insight that changed the way I see life.

III. Fate against Free Will

In Canto XIX of the Inferno we encounter the simonists, clerical figures who sell sacred things for profit. In my own experience, as I shared in that post, I once witnessed a member of the church offering a prayer in exchange for a fee.

As I wrote in that post:

The purpose of prayer is not to bend the will of an unseen supernatural power but to shape the soul, to return us—again and again—to the weight and wonder of existence.

Therefore no one can do it for you, nobody can change your character; the only thing that can is through your own effort. You cannot nominate somebody to climb the mountain of Purgatory for you.

Dante does not aim to climb the steep mount of the Purgatory so he could get some supernatural privileges, he does so to change his character and thus his fate.

And here, my reader, I need to ask your assistance, in the same way as Dante invokes Virgil, for I am going to attempt to articulate a complex thought, a thought that changed my philosophical outlook, as best as I can. This is, perhaps, the most difficult idea that I have had to put on paper for a while.

The “roll of the dice,” which here symbolises life’s outcome, is not random in the Dantean (and Boethian) worldview. The result depends on how much effort you’ve invested in shaping your character, on the quality of the soul you have cultivated.

In this view, divine forces are not absent from the game; they are present in the fall of the dice itself. A ship that sails without alignment to the stars may occasionally catch a favourable wind, but more often drifts aimlessly. A ship aligned to the stars, however, finds that every kind of wind becomes favourable.

Virgil would say: ‘Accept the wind, no prayer can change it’. Boethius would say: ‘You cannot change the wind, but align your ship to the stars, and every wind will be favourable.’

Phew!5

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. The Count Ugolino Returns

Now your inhabitants are never free from war,

and those enclosed within a single wall and moat

are gnawing on each other.

(Hollander’s translation of lines 82-84)

Dante uses here the dreadful image of Ugolino, whose story we explored in this post.

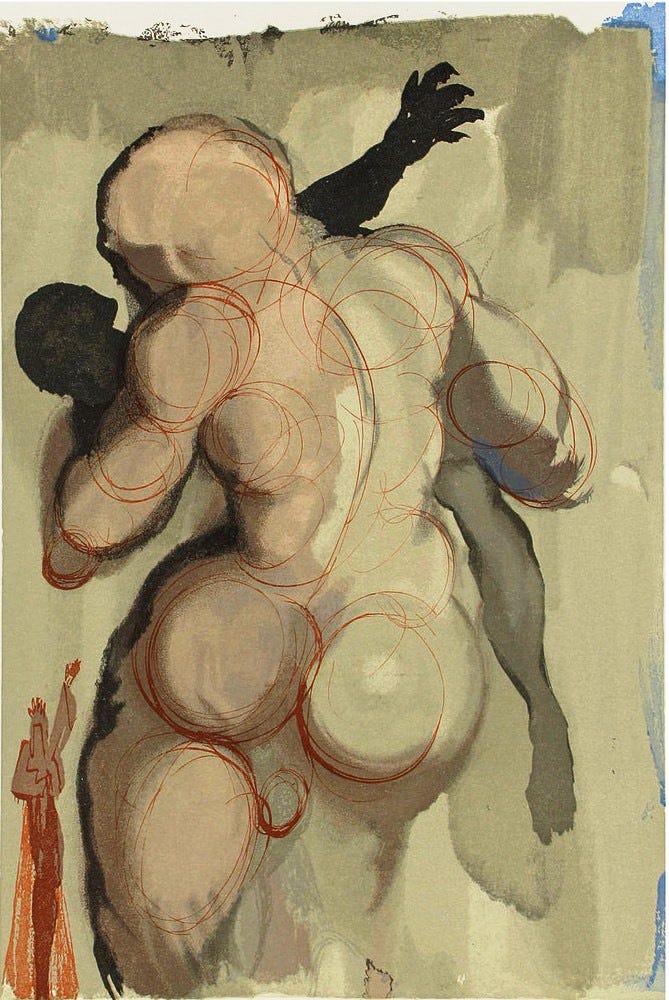

II. Embrace

Virgil embraces Sordello when they discover their shared identity—a moment of quiet, profound beauty. It reminds us that beyond all political divisions, we are bound by a common humanity.

Both were poets, which adds a layer of poetic grace to the scene, especially following Dante’s lament over a blood-stained, divided Italy.

In the end, the message is simple: we are all human. And that, above all, must be remembered.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

The passages that I keep as reminders of wisdom were already included above. The lines on prayer and playing dice are beautiful. Here, I thought to add one that we can all relate to, wherever you live, when we feel like our civilisation is a ship in harsh seas:

Ah, abject Italy, you inn of sorrows,

you ship without a helmsman in harsh seas,

no queen of provinces but of bordellos!

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on Purgatorio 113

Robert Hollander, Purgatorio 130-131

Singleton 122, quoting the commentator Landino.

Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory 115

Apologies for this conversational ‘Phew’ at the end. I tried to “align the stars” in my mind to constructively and structurally express this idea that is slowly growing in my head. Whether I succeeded or not, it is for my reader to judge.

>the glory of Rome is as degraded as a noble beauty condemned to a brothel.

wew!