The Soul Dies Before the Flesh: How Not to Die Alone

(Inferno, Canto XXXIII): The Tower of Hunger, Count Ugolino, Ruggieri and Fra Alberigo

Most men die at 27, we just bury them at 72,

~ Mark Twain

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

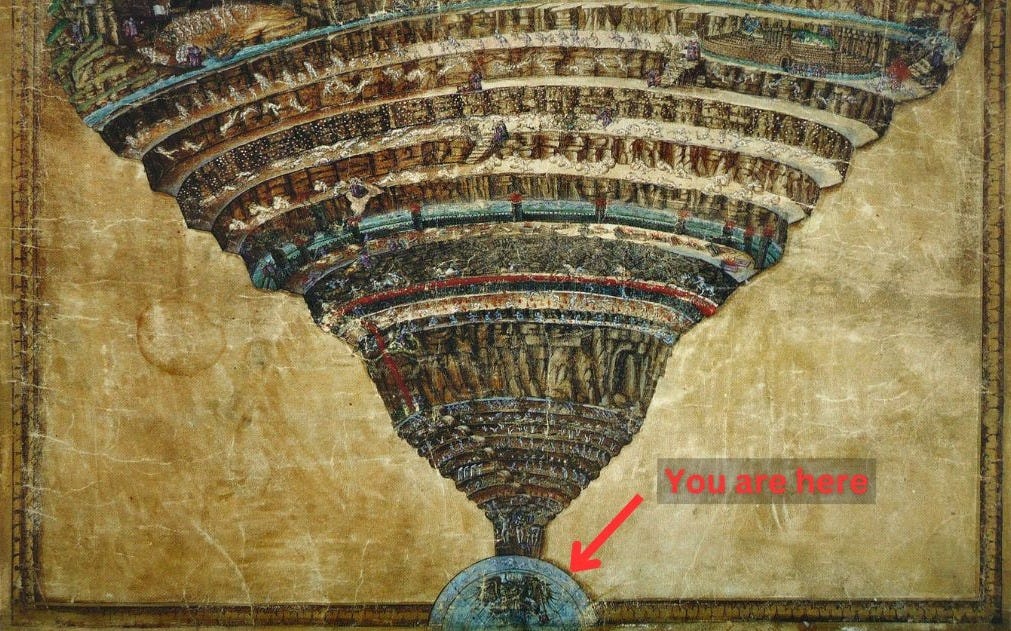

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Thirty-third Canto we arrive in the third ring of the Ninth Circle and encounter the Traitors to Guests. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Count Ugolino’s gruesome meal and tragic story - Ninth Circle, moving from the second ring of Antenora to the third ring of Ptolemea - Traitors against their Guests - The sinners frozen tears - Fra Alberigo and Branca Doria, souls in Hell but bodies on earth inhabited by demons.

Canto XXXIII Summary:

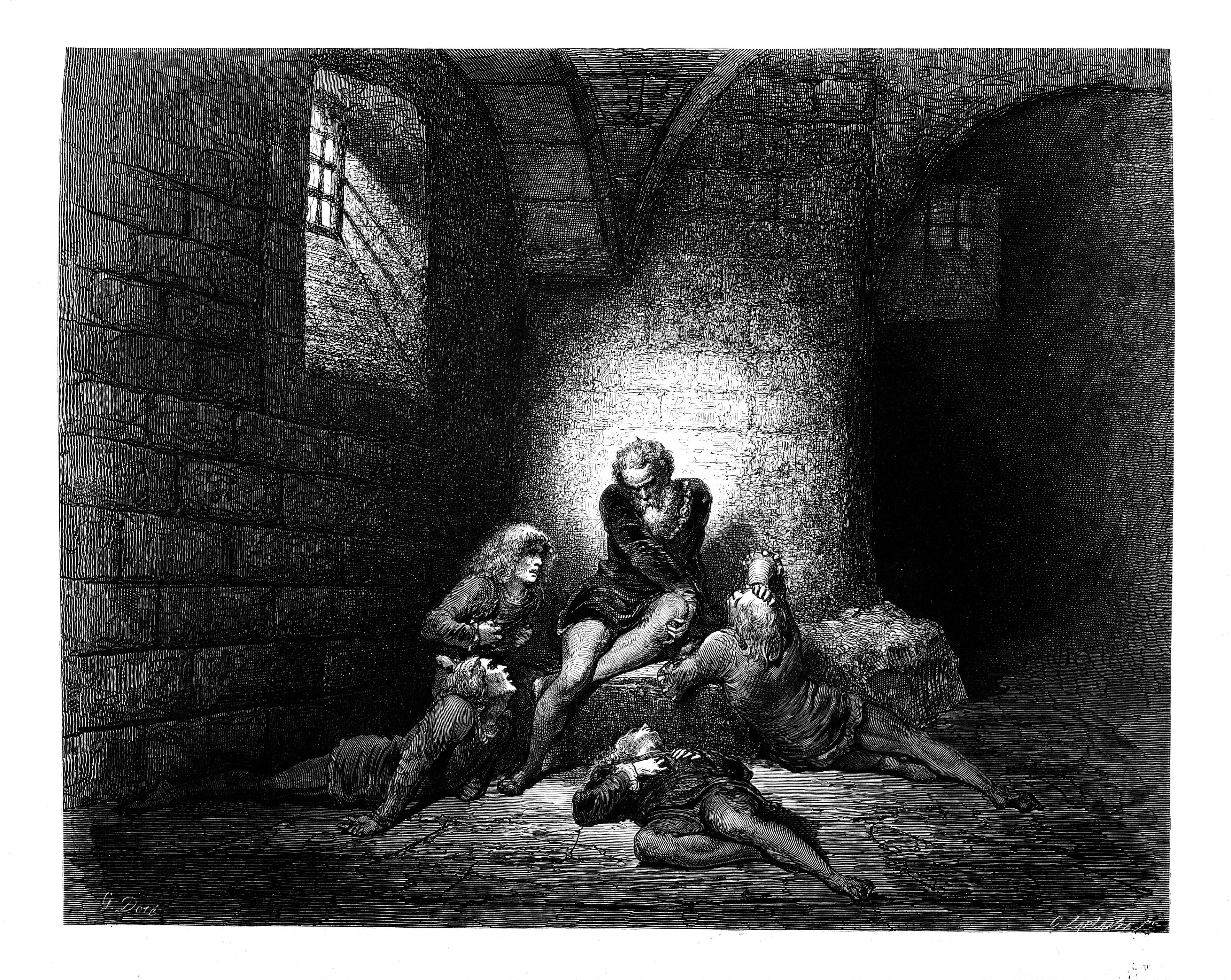

The sinner feasting on the head of his companion prepares to speak to Dante, in what may be the most gruesome opening of any Canto in the Inferno. He lifts his head from his hellish meal, wipes his mouth on the hair of the other, and prepares to answer the request put forth by Dante at the end of Canto XXXII, who promised him acknowledgement in the world above in return for his story. Count Ugolino della Gherardesca begins his story.

Then he began: “You want me to renew

despairing pain that presses at my heart

even as I think back, before I speak.

But if my words are seed from which the fruit

is infamy for this betrayer whom

I gnaw, you’ll see me speak and weep at once.

XXXIII.4-9

Compare this opening sentiment of Ugolino, where the pain of recalling the memory of his misfortune is as terrible as the recounting of it, to that of the lover Francesca in recalling her tragedy:

And she to me: “There is no greater sorrow

than thinking back upon a happy time

in misery-and this your teacher knows.

Yet if you long so much to understand

the first root of our love, then I shall tell

my tale to you as one who weeps and speaks.”

V.121-126

This sentiment of a painful recall is one that Dante found in Virgil, as Aeneas recounted the destruction of Troy to Queen Dido in Carthage:

Words can’t express, my queen, what you bid me relive, all the rueful pain…

Still, if you’re so much enamored with learning how ruin befell me,

also with hearing, though briefly, of Troy’s last afflictions, its death-throes,

though my soul, still shocked by the memory, recoils from the anguish,

let me begin.

Aeneid II.3, 10-13

Count Ugolino recognizes Dante as a Florentine from his speech, and points out the soul upon whom he is feasting as Archbishop Ruggieri. He makes the disclaimer that “there is no need to tell you” (XXXIII.16) the broad strokes of the story, as it was so well known in the world above; but Ugolino, with Dante as witness, can now tell him the details of his awful ordeal.

Ugolino della Gherardesca, the Count of Donoratico, belonged to a noble Tuscan family whose political affiliations were Ghibelline. In 1275 he conspired with his son-in-law, Giovanni Visconti, to raise the Guelphs to power in Pisa. Although exiled for this subversive activity, Ugolino (Nino) Visconti took over the Guelph government of the city. Three years later he plotted with Archbishop Ruggieri degli Ubaldini to rid Pisa of the Visconti. Ruggieri, however, had other plans, and with the aid of the Ghibellines, he seized control of the city and imprisoned Ugolino, together with his sons and grandsons, in the “tower of hunger.”1

Ugolino was imprisoned in the Eagles Tower, so called because of its protective space for moulting eagles, but his experience renamed it the Hunger Tower. His sons were Gaddo (67) and Uguiccione, (89) and his grandsons were Nino (nicknamed Brigata) (89) and Anselmuccio (50), the younger brother of Nino. The account portrays them as quite young, but the youngest, Anselmucchio, was about 15 at the time of his death.

They had been imprisoned for several months when Ugolino had a dream that served as an omen as to his future, in which a wolf and his young cubs were hunted down by Ruggieri on Monte di San Giuliano — the mountain which rose between Pisa and Lucca — with his pack of hounds, led by Gualandi, Sismondo and Lanfranchi, all prominent Ghibellines. In the dream, the wolves and cubs grew weary and were taken down by the pack, the people who were urged on against Ugolino by the Archbishop and his followers. As he awoke from his dream, he heard his sons weeping in their sleep, crying for bread.

You would be cruel indeed if, thinking what

my heart foresaw, you don’t already grieve;

and if you don’t weep now, when would you weep?

XXXIII.40-42

As they waited for their daily meal, they instead heard the door below being nailed shut, adding the fear of starvation to the uncertainty of their imprisonment. In the days of misery that followed, their faces grew haunted; his children and grandchildren saw him suffer so deeply that they offered themselves as the ultimate sacrifice:

Father,

it would be far less painful for us if

you ate of us; for you clothed us in this

sad flesh—it is for you to strip it off.

Then I grew calm, to keep them from more sadness;

through that day and the next, we all were silent;

O hard earth, why did you not open up?

XXXIII.60-63

After four days of starvation, Ugolino’s son Gaddo fell down at his feet and died, after crying out “Father, why do you not help me?” (69)

Canst thou endure, O Earth, to bear a crime so monstrous? Why dost not burst asunder and plunge thee down to the infernal Stygian shades and, by a huge opening to void chaos, snatch this kingdom with its king away?

Seneca, Thyestes 1006-1009

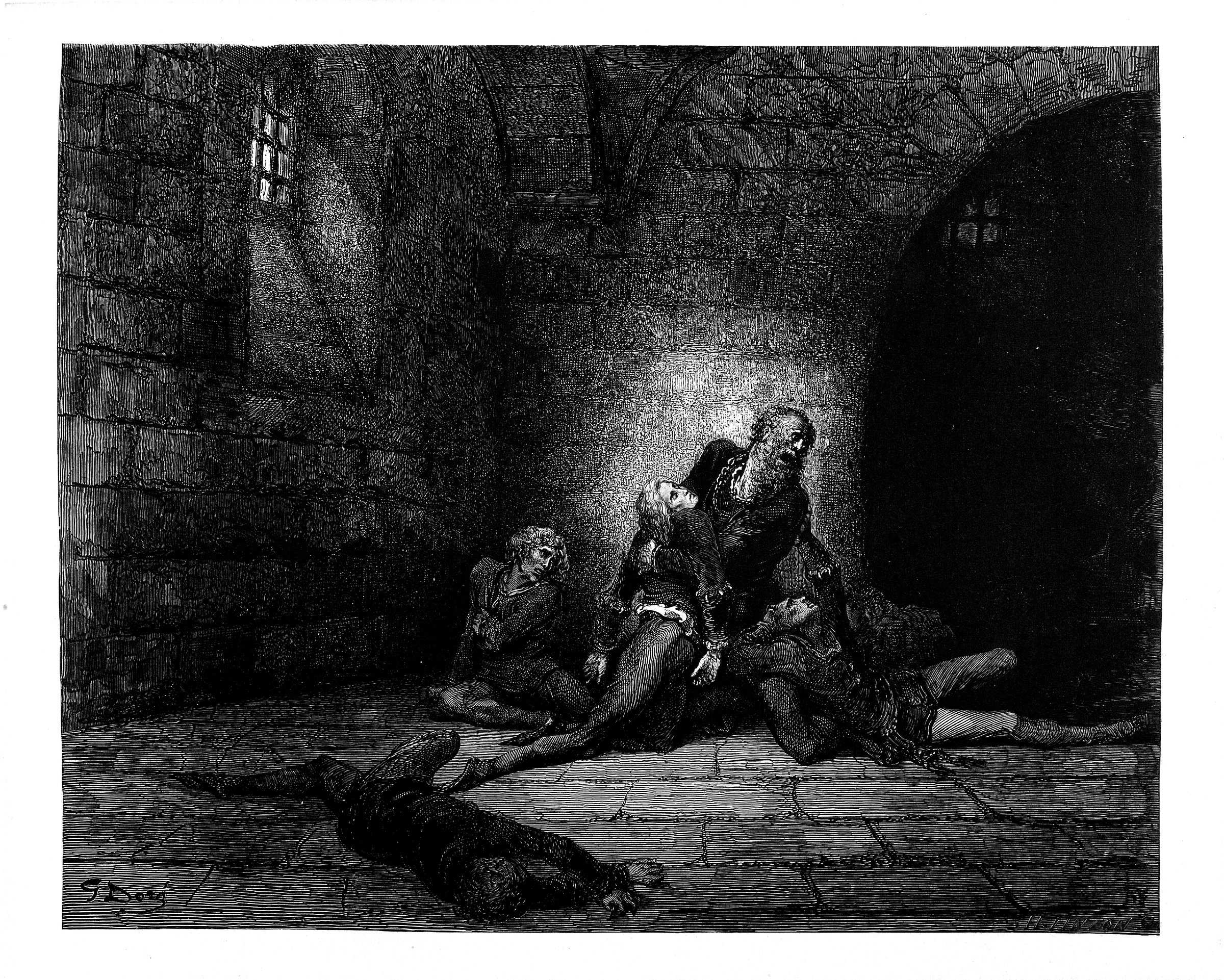

In the blind grief that Ugolino endured, watching his sons and grandsons die, he sought out their dead bodies until he too, was overcome by starvation and died.

Ugolino ended his tale and returned to his gruesome feast. Dante curses Pisa for the crimes that she has contained, and calls to the islands of Capraia and Gorgona, that they might join together in the Arno river to create a dam that will flood Pisa and remove her from the face of the earth. The punishment inflicted on Ugolino’s innocent family seemed the highest of crimes. So degraded was Pisa that it was like Thebes, that city of antiquity which was also notorious for its horrors.

We passed beyond, where frozen water wraps—

a rugged covering—still other sinners,

who were not bent, but flat upon their backs.

Their very weeping there won’t let them weep,

and grief that finds a barrier in their eyes

turns inward to increase their agony;

because their first tears freeze into a cluster,

and, like a crystal visor, fill up all

the hollow that is underneath the eyebrow.

XXXIII.91-99

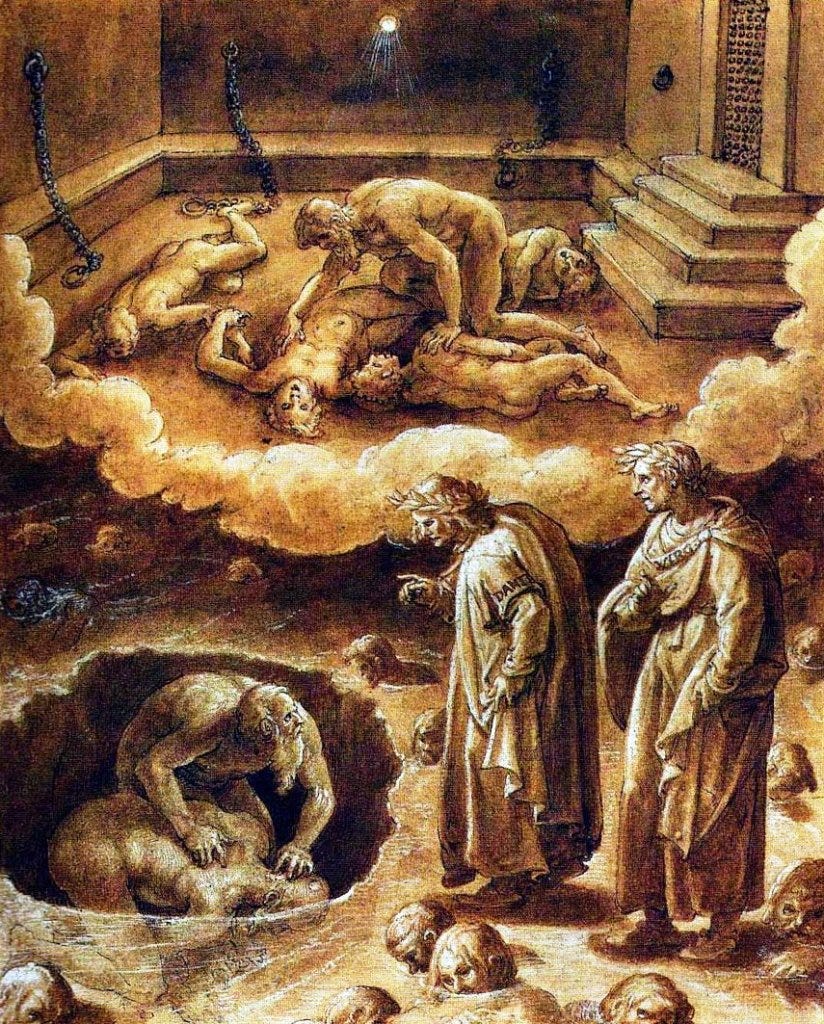

Dante and Virgil have passed the barrier of Antenora to that of Ptolomea, the penultimate ring of Hell - here suffer Traitors against their Guests.

Here lie the traitors to Hospitality; they who denied the most primitive of human sanctities are now almost sealed off from humanity, they cannot even weep. And they are dead to humanity before they die; that which seems to live in them on earth is only a devil in human form - the man in them has withdrawn out of reach into the cold damnation.2

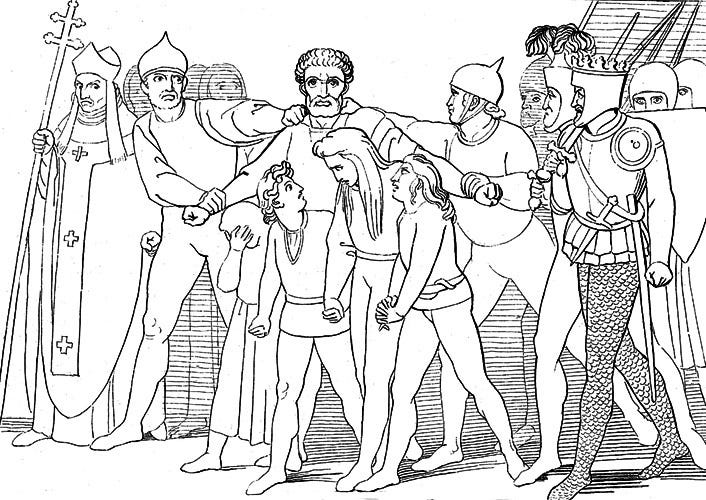

Commentators give two possible sources for this name. The first comes from the Apocryphal Biblical account of Ptolemy, captain of Jericho, who murdered Simon the Maccabee and his two sons at a banquet held in their honor:

[Ptolemy] received them treacherously in the little stronghold called Dok, which he had built; he gave them a great banquet, and hid men there. When Simon and his sons were drunk, Ptolemy and his men rose up, took their weapons, rushed in against Simon in the banqueting-hall and killed him and his two sons, as well as some of his servants. So he committed an act of great treachery and returned evil for good.

I Maccabees 16:15-17

The other possibility is Ptolemy XII, the Egyptian king who, upon welcoming Pompey to Egypt after the battle of Pharsalus against Caesar, in which he was defeated, had him cruelly assassinated as he stepped ashore. On realizing the treachery which was his downfall, Pompey’s last thoughts were thus:

As he dies he tests himself, and in his breast he turns these thoughts:

‘Future ages which never will be silent about the toils of Rome

are watching now, and time to come observes from all the world

the boat and loyalty of Pharos: think now of your fame.

For you the fates of lengthy life have flowed successful;

the people cannot know, unless in death you prove it,

whether you know how to endure adversity. Do not give way to shame

or resent the author of your fate’

Lucan, Pharsalia VIII.621-628

The significance of the act of hospitality and the bond that was created between guests that had broken bread together cannot be overstated; hence the wickedness of the deceit involved.

The sinners in this ring are still suspended in ice, but rather than frozen with heads down or looking ahead of them, this ring finds them lying back with faces up, their tears creating an icy visor over the sockets of their eyes. Dante felt a wind, which shocked him, knowing how close they were to the still and heavy center of the earth; Virgil tells him that he is not mistaken, and that soon he will find the reason for this wind.

They come upon a sinner who cries out to them to remove the ice from his eyes so that he may be relieved for a moment from his suffering; this one mistakes them for sinners that have been placed in this deepest pit.

O souls who are so cruel

that this last place has been assigned to you,

take off the hard veils from my face so that

I can release the suffering that fills

my heart before lament freezes again.

XXXIII.110-114

Dante crafts a carefully worded promise to this sinner, that if he does not fulfill his promise to free his eyes in exchange for his story, may he be sent to the bottom of the ice; Dante does not keep his promise, but he does go to the “bottom” of the ice, as we shall see.

This soul tells his story; he is Friar Alberigo, who is suffering a most distinctive punishment concerning the possession of souls within a body.

He answered them: “I am Fra Alberigo,

the one who tended fruits in a bad garden,

and here my figs have been repaid with dates.”

XXXIII.118-120

A Jovial Friar of the Manfredi family of Faenza, his younger brother, Manfred, struck him in the face in the course of a dispute. Alberigo pretended to forgive and forget, and later on invited Manfred and one of his sons to a dinner. When it was time for the dessert he called out: “Bring on the fruit!” This was the signal for armed servants to rush in and kill Manfred and his son…”To receive dates for one’s figs” is a Tuscan expression meaning “to get back one’s own with interest.”3

It seems that Friar Alberigo was still alive and known to Dante, hence his surprise to find him there in the ice. It is here that we learn of the quick punishment received for those who betray their guests.

For Ptolomea has this privilege:

quite frequently the soul falls here before

it has been thrust away by Atropos.

And that you may with much more willingness

scrape these glazed tears from off my face, know this:

As soon as any soul becomes a traitor,

as I was, then a demon takes its body

away—and keeps that body in his power

until its years have run their course completely.

XXXIII.124-132

Atropos is the third of the three Fates; Clotho spun the thread of a mortal life, Lachesis measured its length, and Atropos snipped it off at death.

Let death come upon them; let them go down alive to Sheol; for evil is in their homes and in their hearts. Psalm 55:15

Alberigo names another soul there with him who has also been replaced by a demon on earth: Ser Branca Doria. Dante is in disbelief, as he knows this one. Branca murdered Michele Zanche, his own father-in-law, with the help of another family member. Friar Alberigo tells Dante that Branca’s soul arrived so quickly there in Ptolomea, that Zanche’s murdered soul did not have a chance to arrive first in the river of pitch among the barrators. After sharing this, Alberigo asks for Dante’s promise to be fulfilled, that he remove the ice from his eyes for having told him his story.

“I did not open them.

To be mean to him was a generous reward.

XXXIII.149-150

Dante is amazed at an evil so great that it could cause souls to flee their bodies.

💭 Philosophical Exercises: How not to die in loneliness and why the soul dies before our flesh

Géricault soon understood why Corréard was eating lemons in such large quantities. The acid taste of the fruit helped the young engineer to rid of the foul taste of human flesh he devoured whilst on board that damned raft.

A society is three meals away from chaos, or, only four hungry days away from cannibalism. When the great French painter Théodore Géricault came to speak to a survivor of the frigate Méduse disaster, he was surprised to see how the sailor and engineer Alexandre Corréard used to eat whole lemons, almost one after another.

At first, Géricault couldn’t understand the appeal of such a sour snack, but when Corréard revealed what had happened aboard the doomed raft, the blood in Géricault’s veins froze, like the icy lake we are now crossing in Dante’s Inferno.

In 1816, the French frigate Medusa (Méduse) ran aground off the coast of West Africa. As the ship began to sink, it became clear there weren’t enough lifeboats for everyone on board. Thanks to Corréard’s skill and ingenuity, a raft was constructed, one that would soon reveal the fragility of human nature and how quickly the line between good and evil can dissolve when circumstances turn dire.

The captain of the ship, an inexperienced navigator, panicked when he realized that the lifeboats could no longer tow Corréard’s raft. He gave the order to cut the rope that connected them, severing the last thread of hope for those left adrift.

What followed on the raft was the story despair, death and cannibalism. I have told this story in detail in my piece called Géricault: What Happens When You Lose Hope

When Géricault came to hear Corréard’s story in the autumn of 1817, he was already working on a painting - an enormous canvas that one can stand before and admire with a terrified heart. A painting that captured both the agony of the dead and the despair of the survivors on that doomed raft.

That painting is The Raft of the Medusa.

If my reader looks closely at this terrifying scene, they will notice an old man, covered by a red drape, holding the lifeless body of a young naked man in his right hand, while resting his head in the left.

Before I reveal who he is (though I suspect you’ve already guessed) look once more: the old man stands at the very center of the raft, dividing it into two halves. He gazes toward the corpses, his back turned to those who still cling to hope, those who believe they’ve spotted a ship on the horizon.

The figure who marks the boundary between hope and despair is none other than Count Ugolino himself.

II. The Raft and Tower: Hunger and Cannibalism

Both Théodore Géricault and his friend Eugène Delacroix were deeply obsessed with Dante’s Divine Comedy, and Géricault could not unsee the connection between the story of Ugolino and his sons and that of the Medusa and its survivors.

Ugolino’s story unfolds over seven harrowing days: on day one, Archbishop Ruggieri orders the door to be nailed shut just as the captain of the Méduse severs the raft’s towline, abandoning those on board. Day two brings the onset of hunger: mirrored by the growing desperation on the raft. On day three, silence descends: while on the raft, the fight for dwindling supplies begins. Day four is marked by Gaddo’s cry and death: on the raft, the first signs of cannibalism emerge. On days five and six, Ugolino’s remaining sons perish: death continues on the raft as despair gives way to brutal survival. Finally, on days six and seven, Ugolino is left with grief and death: just as those on the raft face either the last spark of hope or the full weight of hopelessness.

Let’s look at the painting closely again, what do we see on the left hand of Ugolino? It looks like a band-aid, it is covered in blood. Interestingly enough in this canto, Ugolino, silent, biting his hands from grief, causes the children to think that he is hungry, and they offer themselves to him for food.4

Father,

it would be far less painful for us if

you ate of us; for you clothed us in this

sad flesh—it is for you to strip it off.’(lines 61-63)

Truly terrifying words for anyone to say.

But equally terrifying are the last words of Ugolino, these verses freeze one’s heart immediately:

now blind, I started groping over each;

and after they were dead, I called them for

two days; then fasting had more force than grief.”

Matter overpowers soul. The stomach conquers grief. It is worth recalling that in Christian symbolism, bread is not merely food: it is the flesh of Christ, a sacred offering. To eat, in desperation or in betrayal, is not just to survive, but to desecrate.

If we shift our gaze once more from Dante’s profound moral vision to Géricault’s haunting brushstrokes, we notice that before the old man lie four lifeless bodies: four dead sons. Just as in the tower, Ugolino is alone. He has turned his back to hope, fallen into silence, frozen in grief. His face, like stone, betrays no emotion; his body, motionless, speaks of a suffering too deep for tears.

In this emotional tangent, allow me to say how grateful I am to have been born into a world shaped by geniuses, whose works are so richly layered and profoundly interconnected that one could spend a lifetime studying them, and still find new wisdom every time one returns.

III. Philosophical Exercises: How not to be alone

What can we learn from Ugolino? What is the wisdom behind these terrifying lines?

Ugolino is placed in Antenora, the part of Cocytus reserved for those who betrayed their homeland or political party. Dante does not explicitly spell out the precise betrayal that condemns Ugolino, but the historical figure was infamous for shifting alliances and acts of political treachery, earning him a place among the traitors of the state.

Ruggieri who placed Ugolino and his sons into that tower to starve was also infamous for the same acts of treachery.

Thus two traitors, souls steeped in treachery, meet in the depths of the Inferno, and I believe Ugolino’s fate carries a profound lesson: that the treacherous die alone, trapped in the towers of loneliness and isolation they have built for themselves.

No one came to Ugolino’s rescue. No one saved his innocent sons. Even thieves can find a kind of trust among one another, united by a shared crime. But traitors and betrayers, by the very nature of their sin, sever every thread of trust that binds them to others. So when their moment of need arrives, no one comes because, in the end, what remains in their character that is still worth saving?

At the front of Géricault’s raft, we see a Black man raising his arm, signalling desperately to the ship on the horizon. He is supported by the muscular arms of a man behind him; his right leg rests on another figure who, too, signals with a white cloth. This is more than a cry for rescue—it is the soul triumphing over the flesh. These figures embody the bonds of trust that survived even the madness of cannibalism. This is loyalty. This is not merely the survival of the body, but the survival of the human spirit.

(More on Ruggieri and Alberigo in the Themes section below—they are just as astonishing.)

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Alberigo: Soul Dies Before the Flesh

He answered then: “I am Fra Alberigo,

the one who tended fruits in a bad garden,

and here my figs have been repaid with dates.”“But then,” I said, “are you already dead?”

And he to me: “I have no knowledge of

my body’s fate within the world above.For Ptolomea has this privilege:

quite frequently the soul falls here before

it has been thrust away by Atropos.(lines 118-126)

Unbelievable are the words of Fra Alberigo, condemned to this deepest part of Inferno for the treachery of murdering his guests beneath his own roof. What makes his confession so astonishing is the revelation that one need not die for the soul to descend into Hell. His presence here tells us that certain ways of living—certain choices, patterns, and betrayals—can damn the soul while the lungs still breathe and the stomach still digests.

The soul is its own place; within it are both heaven and hell. Alberigo is still alive in the world above, yet his soul is frozen in eternal punishment. Dante, too, is alive as he descends through these circles, but his soul remains open: searching, learning, striving toward virtue. And that is why there is still hope for him.

Fascinating!

Ugolino dominating over Ruggieri

A wonderful scholar Frances Yates, who wrote many fascinating books and articles, pointed out that Ugolino is dominating Ruggieri. Both of them were treacherous and yet Ruggieri was cruel towards Ugolino. Only the Divine thought can bring justice, and thus Ruggieri’s punishment is not only being in this lowest point of hell, but also being eaten by the one whom he killed by starvation.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

I apologise for repetition here, but please take this as an opportunity to re-read and pause on this thought once again. We must be aware of our inner climate.

He answered then: “I am Fra Alberigo,

the one who tended fruits in a bad garden,

and here my figs have been repaid with dates.”“But then,” I said, “are you already dead?”

And he to me: “I have no knowledge of

my body’s fate within the world above.For Ptolomea has this privilege:

quite frequently the soul falls here before

it has been thrust away by Atropos.(lines 118-126)

Mark Musa, The Portable Dante 180

Sayers Hell 283

Sayers 284

Hollander’s commentary on Ugolino’s kids offering themselves as bread to their father.

Gruesome as it is, this is my favorite canto so far. Do you think Ugolono’s son’s words, “Father, why don’t you help me!” echo Christ’s words on the cross? Thanks Vashik for sharing your thoughts and research!