False Gold and Rotten Flesh: Alchemy and Achilles's Shield

(Inferno, Canto XXIX): Achilles, Troy, The Fall of Icarus and alchemy

“An old alchemist gave the following consolation to one of his disciples: “No matter how isolated you are and how lonely you feel, if you do your work truly and conscientiously, unknown friends will come and seek you.”

~ Carl Jung, from Psychology of Alchemy

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Twenty-Ninth Canto we enter the tenth and last bolgia of the Eighth Circle and encounter the Falsifiers. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

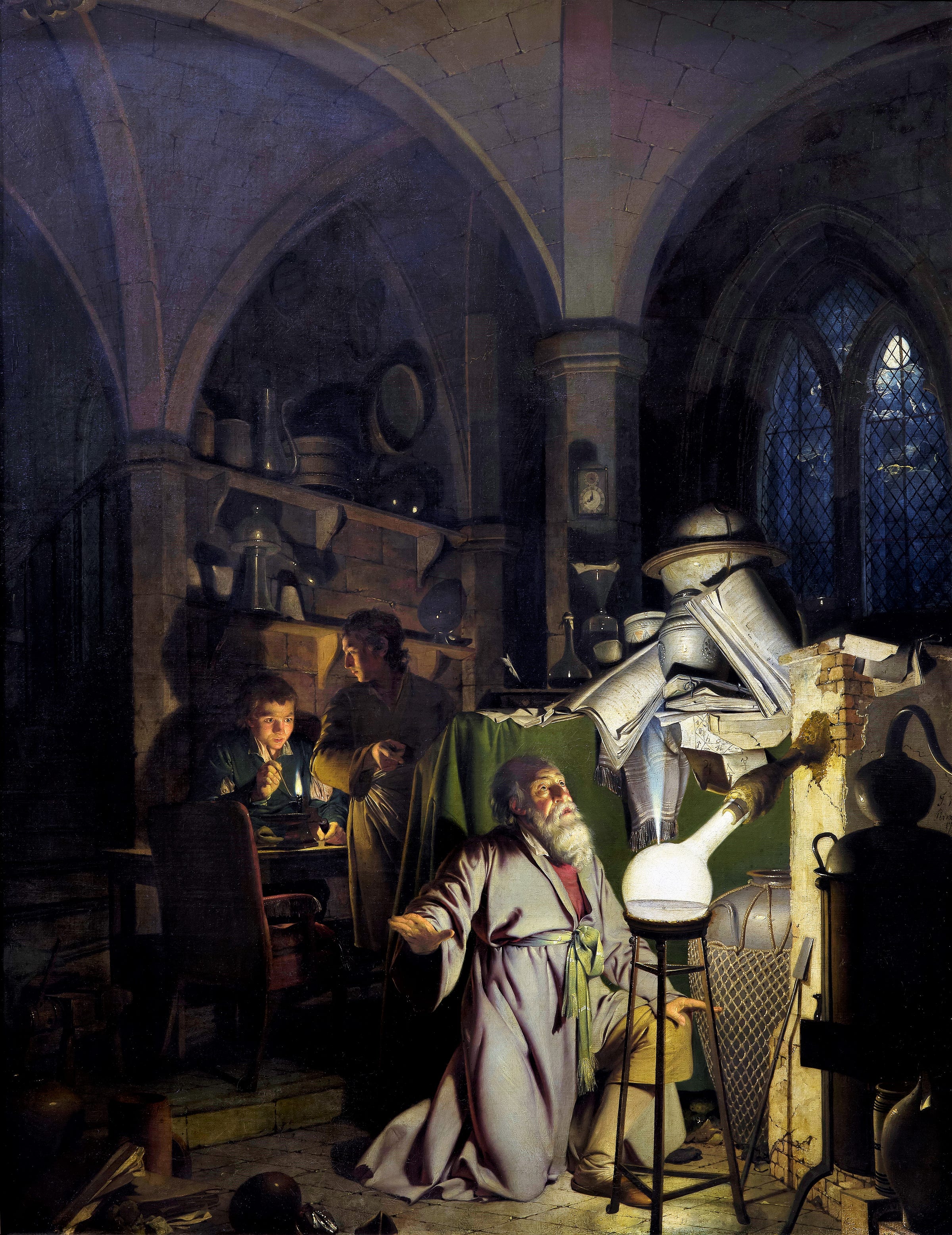

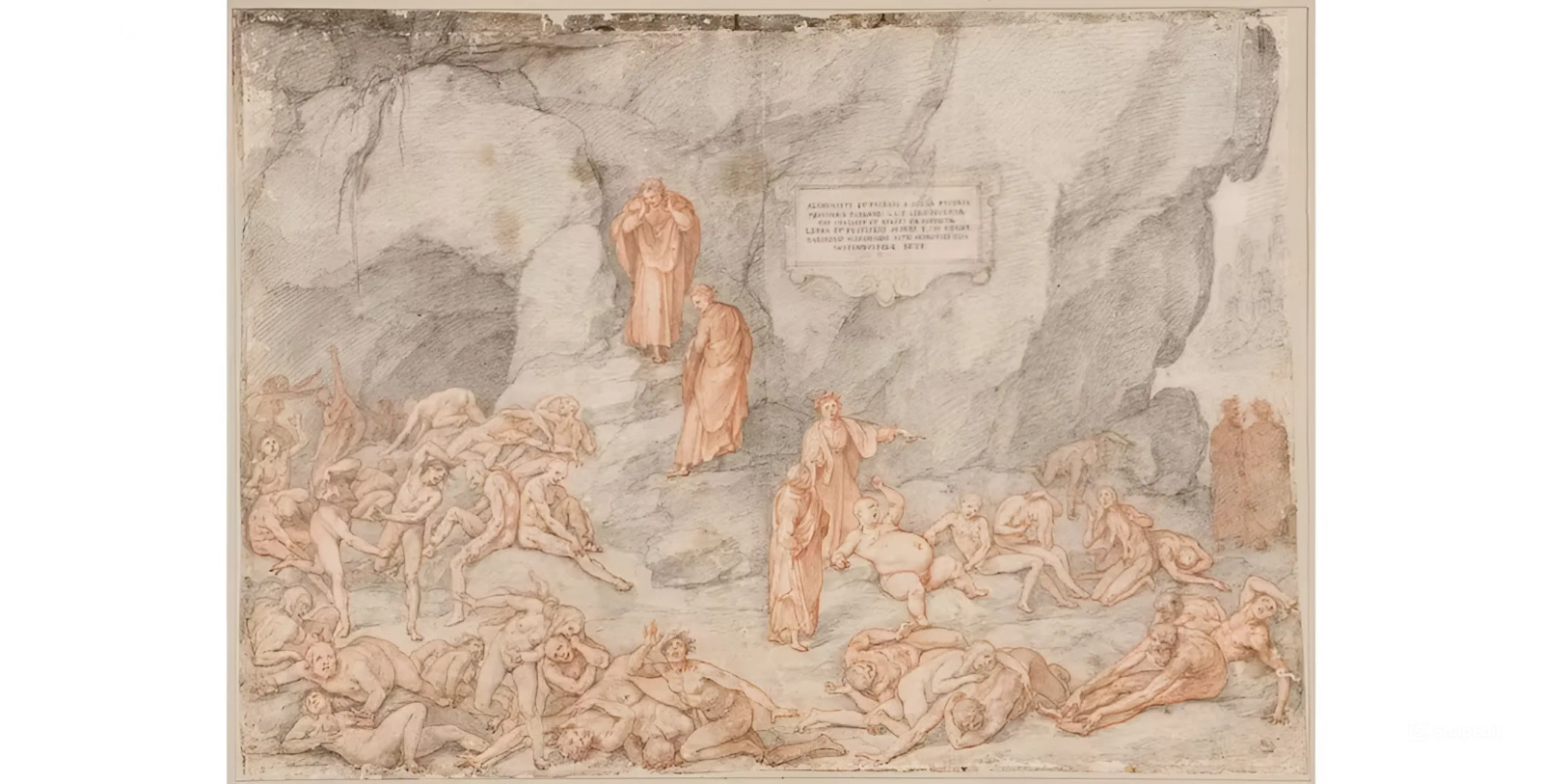

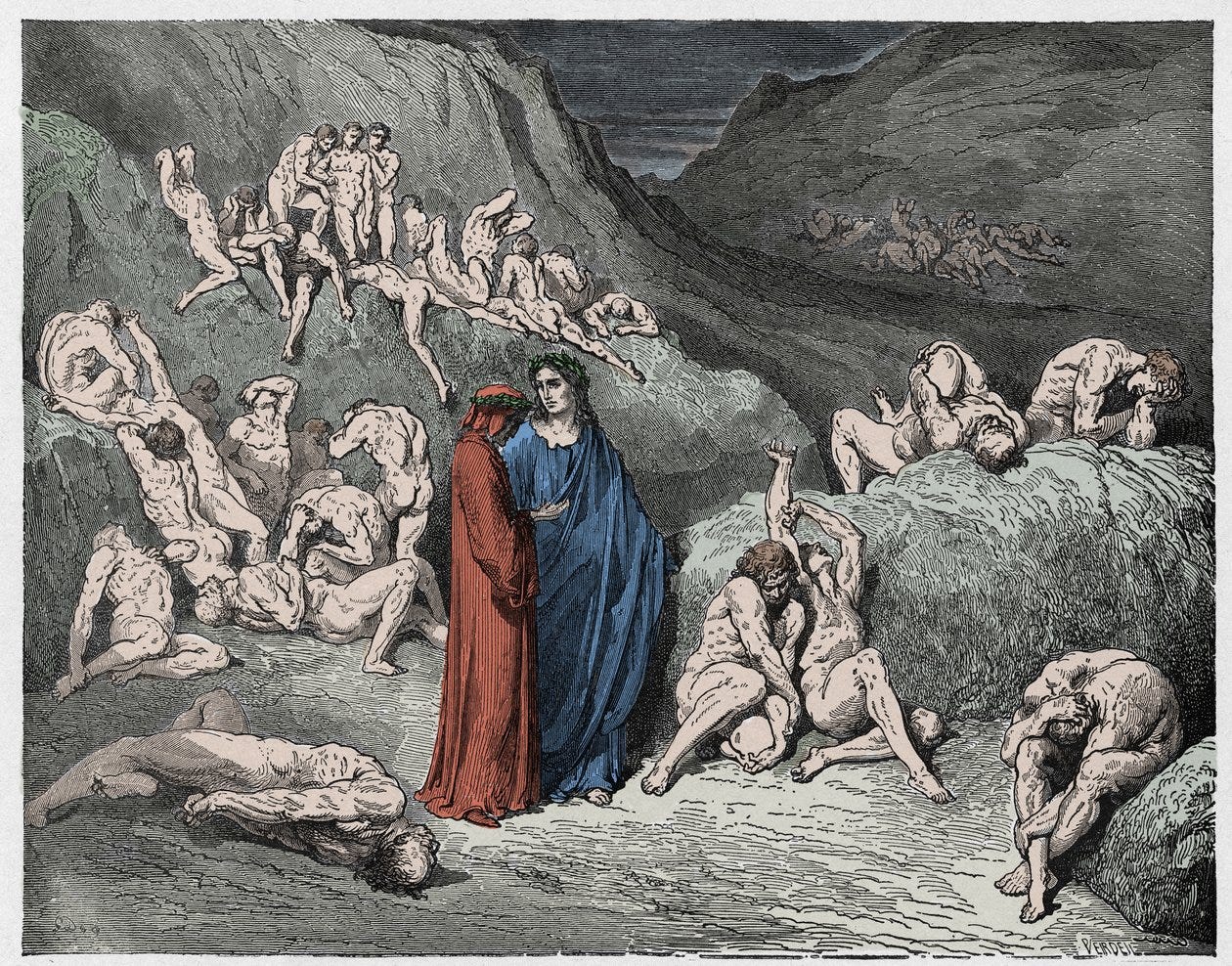

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

End of the ninth bolgia and the Sowers of Schism - Vengeance for Geri Del Bello, Dante’s relation - The tenth and last bolgia of the Eighth Circle - The Falsifiers of Metals - The decay and stench of the sinners leprous scabs and sores - Griffolino d’ Arezzo - The foolish Sienese - Capocchio of Florence.

Canto XXIX Summary:

Dante is reeling from the intensity of the visions they had encountered in the ninth bolgia, the bloody and mutilated Sowers of Schism and Scandal. As much as he was overcome with weeping, he almost could not turn away until Virgil rebuked him for his seemingly unnatural interest in this group, an interest he had not yet shown for other circles.

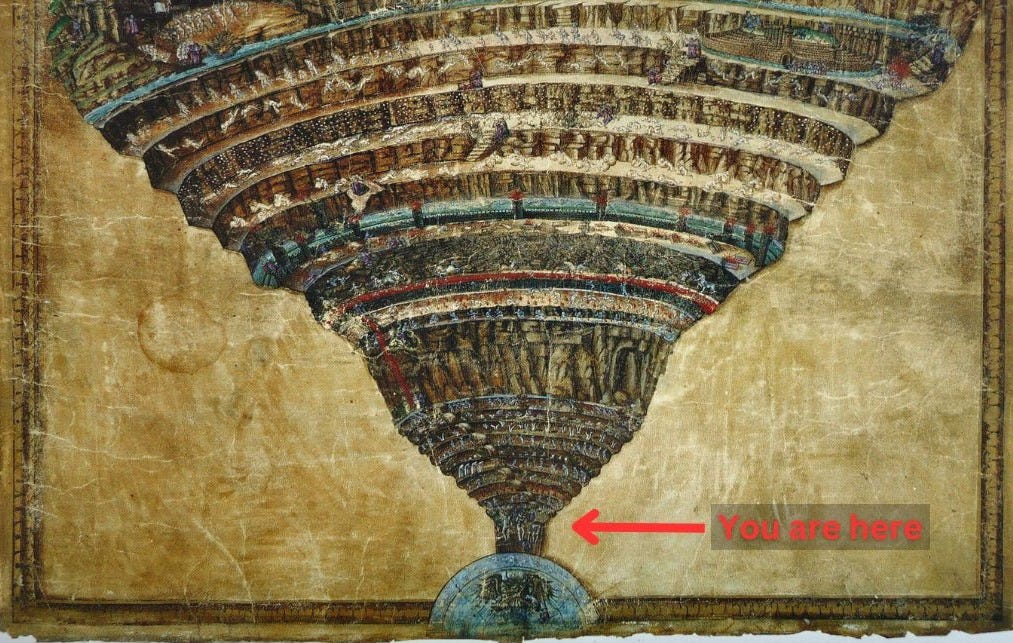

For the first time there is an actual measurement of space in this Canto: “twenty-two miles make up the circuit of the valley,” (8-9) leading to speculation on the size and shape of the entirety of Hell:

If the circumference of this ninth bolgia is twenty two miles, and if that of the next or tenth bolgia is, as we learn in Inf. XXX.86, eleven miles, then apparently the great cavity of Hell is shaped like an inverted cone, becoming narrower in circumference as the wayfarers descend toward the bottom.1

Virgil treats Dante’s unnatural interest in the ninth bolgia sinners with irony, as if he wanted to count each sinner they encountered in this vastness of Hell. He also mentions that their time is short, which gives a sense of the end time by which this stage of their journey must be completed.

This is the first indication that a definite amount of time has been allotted for the descent through Hell, but the reader must wait until the end of that descent to know the total time. The words serve also to signal that the end of the journey through this first realm is fast approaching.2

Yet there was a significant reason for Dante taking his time and looking intently, and he justifies his actions:

In that hollow upon which,

just now, I kept my eyes intent, I think

a spirit born of my own blood laments

the guilt which, down below, costs one so much.

XXIX.18-21

Dante is seeking one from his own family whom he thinks may be in the trench of the Sowers of Schism. Virgil confirms this, but says it is time to “attend to other things” and move on; Virgil had seen the one he was looking for look threateningly at Dante, while another sinner called out his name, identifying him: Geri Del Bello. Yet Dante had not been paying attention as he had been speaking with the sinner holding out his own head as a lantern, the lord of Hautefort, Bertran de Born.3

“My guide, it was his death by violence,

for which he still is not avenged,” I said,

“by anyone who shares his name, that made

him so disdainful now; and—I suppose—

for this he left without a word to me,

and this has made me pity him the more”

XXIX.31-36

Blood feuds and avenging one's relatives were sanctioned by law in Dante’s time4, and therefore pardonable. It was considered proper justice for “anyone who shares his name”, his family members, to enact this revenge. Geri, therefore, was within reason with his threatening gestures, thinking that Dante would have been obliged to avenge him, but had not, and Dante’s increased pity of him is due to this knowledge that one of his own was left unavenged.

The revenger of blood himself shall slay the murderer: when he meeteth him, he shall slay him. Numbers 35:19

There is more to it in this brief mention than meets the eye, however, for “here Dante both recognizes and implicitly rejects the socially divisive custom of the vendetta and the blood-feuds between families in his time.”5

This Geri was a nobleman, brother of Messer Cione del Bello degli Alighieri. He was a troublesome and factious man, and he was murdered by one of the Sacchetti, nobles of Florence…because he had sown discord among them. His death was not avenged for about thirty years. Finally, the sons of Messer Cione and the nephews of this Geri took their revenge, for they killed one of the Sacchetti in his own house.6

As they spoke of Geri, they reached the bridge over the tenth and final bolgia of the Eighth Circle.

When we had climbed above the final cloister

of Malebolge, so that its lay brothers

were able to appear before our eyes,

I felt the force of strange laments, like arrows

whose shafts are barbed with pity; and at this,

I had to place my hands across my ears.

XXIX.40-45

Dante likens the sinners within each trench to groups of brethren of the church, such was their unity of purpose in life; and as the view spread out before them, their terrible cries pierced Dante like arrows, each one hitting him with pity for the suffering below.

Just as Dante had us imagine the throngs of wounded from battle after battle in Canto XXVIII, here he paints the image of the many lying ill in hospitals in the heat of a malarial summer in the marshy region of Maremma, the island of Sardinia, and the valley of the Chiana river. The rot and stench and decay of the trench rose up to meet them in unfathomable waves.

They crossed the bridge and landed on the further bank, the last and deepest bank of the Eighth Circle; from here they could see fully into the tenth bolgia, and the sin of this realm is named: the Falsifiers.

This is the first group of Falsifiers, those who falsified metals, or the alchemists. We will continue to see other falsifiers into Canto XXX; the afflictions suffered depend on what kind of falsification the sinner had practiced. This first group was suffering with the sores and scabs of leprosy, and we will later see the falsifiers of their appearance as mad, those forgers of coins will suffer from dropsy (edema), and those who falsified with lies will suffer from fever.

The total image is of the corruption which results when truth, the basis of social relations and exchange, is abandoned in all these ways.7

In this scene, Dante’s imagery rivals the grotesque suffering as given by Ovid’s telling of the myth of the cursed island of Aegina. Juno, due to her jealousy, sent a plague to the island that killed all the inhabitants - people and animals - of the kingdom of Aeacus; the vivid detail with which he describes that suffering are found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses VII.748-944; Dante mirrors that pestilence and suffering, the sprawling and languishing sinners foul with rot and decay, with barely the energy to drag themselves forward.

According to legend the nymph Aegina, daughter of the river god Asopus, was carried to the island of Oenone by Jupiter, to whom she bore a son, Aeacus. Aeacus eventually renamed the island in honor of his mother; but Juno, jealous of her rival, nearly depopulated the island by infesting it with a pestilence. Aeacus then appealed to Jupiter, who restored the population by changing the ants on the island into men, thereafter called Myrmidons.8

Two sinners stood out to them, so covered in scabs and sores that they clawed themselves desperately in looking for a relief that would never come; the scraping of their scabs reminiscent of scraping the scales off of fish. Virgil speaks and asks if any below are Italian, which the two sinners are. They and others turn to look at Dante, shaky and weak, to see this living soul. Virgil encourages Dante to question them.

The first to speak is Griffolino d’Arezzo, condemned to the trench of falsifiers for the practice of alchemy, or the attempt to turn base materials into gold. This was not his only crime however, his falsifications reached into swindling as well. He is never named in the Canto, but he was identified, as are so many others who are unnamed, by the early commentators.

Griffolino convinced Albero da Siena—who was thought to be either the son of or protege of the bishop of Siena—that he could teach him how to fly; when Albero - who had “curiosity, but little sense (XXIX.114) - realized he had been fooled, he brought a complaint to the bishop, who sentenced Griffolino to be burned alive for practicing magic.

Dante’s jest to Virgil about the vanity and foolishness of the Sienese was overheard by the sinner sitting with Griffolino - Capocchio - who lists other Sienese who were very clearly just as vain and foolish as Albero. The Florentines and Sienese were rival towns, hence the mocking at their expense. Capocchio names Stricca di Giovanni del Salimbeni, a notorious spendthrift, and Niccolo de’ Salimbeni, who introduced luxurious and expensive spices like clove, wasting their resources to excess on frivolities. Both were members of the Brigata Spendereccia, or the Spendthrift Brigade, a group we have seen before with the unfortunate Lano in Inf. XIII.118.

Benvenuto gives an account of this club, which he says was composed of twelve wealthy young men…they each contributed a large amount to a common fund, which the members were bound to spend lavishly under pain of expulsion from the society…They prided themselves on having all sorts of exotic dishes and flung the gold and silver utensils and table ornaments out the window as soon as each banquet was over…In this way they ran through their means in less than two years and became a public laughingstock.9

The sinner who has been speaking, in supporting Dante’s comment, is so far unrecognized by the Poet. He asks Dante to look closely, past the wounds and scabs and decay, to see who it is that he is speaking to. He finally names himself as Capocchio, in Hell for the sin of alchemy.

Capocchio was from Florence, and he was acquainted with the author, for they had been students together. He was a person who, like the performers at court, could mimic anyone or anything he liked, so much so that he looked just like the thing or the man he was imitating. Later he began to counterfeit metals, just as he had done people. 10

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

Alchemy may be compared to the man who told his sons that he had left them gold, buried somewhere in his vineyard; while they by digging found no gold, but by turning up the mould about the roots of the vines procured a plentiful vintage. So the search and endeavours to make gold have brought many useful inventions to light.

~ Francis Bacon

It is a surprising - and almost uncanny - coincidence that Lisa and I found ourselves writing and proofreading this very post on Holy Saturday. Uncanny, because it is precisely on Holy Saturday that Dante and Virgil arrive at this very point in the Inferno XXIX. Is it mere coincidence, or a moment of Jungian synchronicity? We may never know - but I must admit, I find it both deeply moving and deeply inspiring!

I. Achilles’s Shield

The great Greek hero Achilles, the slayer of Hector, who met his end when an arrow struck his heel was a Myrmidon. And the ancestors of the Myrmidons? They were ants. Yes, ants - as in the industrious, relentless insects.

I do not think that there was greater grief

in seeing all Aegina’s people sick

(then, when the air was so infected thatall animals, down to the little worm,

collapsed; and afterward, as poets hold

to be the certain truth, those ancient peoplesreceived their health again through seed of ants)

than I felt when I saw, in that dark valley,

the spirits languishing in scattered heaps.(lines 58 -66)

In Ovid’s telling, Zeus (Jupiter) seduced and abducted the nymph Aegina in the form of a flame.11 From this union, Aegina bore a son, Aeacaus, who would go on to become the king of the island.

This enraged Hera (Juno), who, jealous of Zeus’s passion for the nymph, sent a devastating plague that wiped out the island’s entire population - even the animals and birds.

King Aeacus prayed to his father Zeus for mercy and a way to repopulate the island. The only creatures spared by the plague were the ants - myrmekes (Greek) -and it was from them that Zeus, in answer to his son’s plea, created a new race of men: the Myrmidons. From this lineage came great warriors, among them Peleus, and his son Achilles.

This new race, born from ants, inherited their defining traits: tireless diligence, foresight, ferocity, and unwavering loyalty to their leader. To this day, the Oxford Dictionary defines a myrmidon as one who is unquestionably loyal and completely fearless - a perfect description for the fierce warriors who, under Achilles’ command, stormed the walls of Troy.

II. Falsifiers as the Embodiment of Degeneration

In his brilliant book - Did Greeks Believe Their Myths? - the French historian Paul Veyne describes with exceptional clarity how the Ancient Greeks believed in their deities and stories.

If we examine the myth of the Myrmidons through the lens of Paul Veyne, we might interpret Hera (Juno) not as a figure of romantic jealousy, but as an embodiment of Nature itself. Her “jealousy” is not emotional, but corrective - an expression of Nature’s impulse to restore balance when human ambition overreaches its bounds through a transgressive union with the divine, symbolised by the illicit affair with Zeus (Jupiter).

Only through hard work, relentless effort, and far-sighted vision can a civilisation aspire to the glory of the Myrmidons. Any other path is illusion. Those who promise to turn lead into gold without the toil of mining the precious metal spread not wisdom, but a plague—a contagion of falsity that corrodes the very foundations of truth and labour.

If ants, in their diligence and order, gave rise to the great race of Aegina, then falsifiers (such as alchemists), by contrast, degenerate the human race - reducing it not to ants, but to vermin: mindless, crawling, parasitic.

III. Daedalus: Falsifiers Fly to Close to the Sun

It’s true that I had told him—jestingly—

‘I’d know enough to fly through air’; and he,

with curiosity, but little sense,wished me to show that art to him and, just

because I had not made him Daedalus,

had one who held him as a son burn me.But Minos, who cannot mistake, condemned

my spirit to the final pouch of ten

for alchemy I practiced in the world.(lines 112 - 120)

Daedalus was an architect and master craftsman; it was he who designed the labyrinth for King Minos of Crete in which the infamous Minotaur was imprisoned. And it was he, too, who fashioned the fabled wings - an ingenious contraption of feathers and wax - with which he and his son Icarus attempted to flee the island of Crete

In this canto, we meet Griffolino d’Arezzo, whose punishment in this bolgia reveals a disturbing Ovidian-like metamorphosis - through the grotesque suffering inflicted upon him, he (as other damned of this bolgia) gradually degenerates from a human being into something closer to an insect.

Griffolino was no Daedalus, so his false promises were exposed and he was burned at stake as a heretic, but as he tells us himself: ‘Minos, who cannot mistake, condemned my spirit to the final pouch of ten for alchemy I practiced in the world’

It has been a long time, so I will remind my reader—although you certainly remember—that the punishment in Inferno and Purgatorio is allocated “by the sin that made them lose their ‘reason.’”12 We explored this in the post I link below, but in its essence, Griffolino was punished by the Sienese for being a heretic; however the Divine justice places him in the bolgia for falsifiers.

Like Icarus, who was told explicitly by his father Daedalus not to fly too close to the sun, Griffolino promised Albero of Siena that he had knowledge that could make him equal to God, he falsified the very nature of truth and real understanding of the world.

IV. Final words: Isaac Newton, Alchemy, and limits of our understanding

In the next canto, we’ll meet all four types of falsifiers and explore each of them in greater depth. But before we descend further, I’d like to conclude this section by drawing your attention to a wonderful essay by physicist Carlo Rovelli titled Newton the Alchemist, which I briefly wrote about it here.

Isaac Newton, surprisingly to some, was indeed an alchemist—but of a particular kind. He explored various alchemical theories not out of blind belief, but through rigorous experimentation. And when he found no truth in those ideas, he abandoned them. He never published his alchemical writings -not because he feared ridicule, but because, as a scientist, he had proven to himself that they lacked substance.

Would Dante have placed Newton alongside Griffolino for his foray into alchemy? My humble answer is a firm no. Newton’s curiosity was not rooted in deceit, but in the pursuit of truth. His experiments ultimately exposed alchemists as falsifiers. In doing so, Newton did not promote falsehood - he uncovered it.

(More on the interconnection between alchemy and the development of science in this post.)

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

The length of the journey

For the first time, Dante gives us a precise measurement of this bolgia - 22 miles. Some commentators have speculated that as we descend deeper into the Inferno, this distance is halved with each successive bolgia. I haven’t yet fully explored this theory, but if we were to follow that logic backward, Limbo would span an astonishing 1,100 miles in diameter! (some estimates could indicate to it being between 1,100 to 4000 miles, depending on calculations!)

Of course, this is purely speculative, but it opens the door to fascinating mathematical and symbolic interpretations of Dante’s architecture of Hell. Once our read-along concludes, I plan to delve into these kinds of curious details and hidden structures within The Divine Comedy. There’s so much more to uncover.

Also, the entire journey of Dante and Virgil through Hell takes 24 hours, which is mind-blowing! Thinking about this… the fact that we are exploring this very canto on Holy Saturday makes the whole experience feel even more uncanny, as if the layers of history, poetry, and spiritual mystery have aligned for a moment.

This isn’t just a coincidence—it feels like one of those rare convergences that Dante himself would have seen as a sign. Holy Saturday is the day of silence, of descent, when Christ, according to tradition, entered the realm of the dead. And here we are, with Dante and Virgil, nearly at the bottom of the Inferno, surrounded by silence, loss, and the lingering hope that something lies beyond.

Schismatics: Dante weeps for all of us

We’re all familiar with the legendary rivalries that once tore Florence apart - like the bitter feud between the Pazzi bankers and the Medici. Dante’s own family, the Alighieri, was not exempt from such vendettas.

At the start of this canto, Dante becomes visibly emotional when he sees the spirit of Geri del Bello, his father’s cousin, who was murdered in a family feud. Geri’s death had gone unavenged by the time The Divine Comedy was written, a fact that weighs heavily on the poet’s heart.

This moment opens up one of the canto’s central themes: the devastating impact of intergenerational violence and how it erodes the very soul of a city. Florence, in Dante’s eyes, was being slowly consumed by such hatreds.

Yet there’s another layer to Dante’s tears, beyond family loyalty. Standing now near the end of his descent, perhaps Dante is grieving not just for Geri, or even for Florence, but for humanity itself for the countless ways the human psyche turns against itself, destroying what it should protect.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

At this my master said: “Don’t let your thoughts

about him interrupt you from here on:

attend to other things, let him stay there;

Singleton, Commentary on Inferno 527

Singleton 527

See Inf. XXVIII.134

Singleton 530

Mandelbaum Inferno 610

Singleton quoting the medieval commentator Benvenuto 529

Mandelbaum 611

Singleton 531

Singleton 540

Singleton 543

A reminder that Ulysses, whom we met in the circle of evil counsellors, presented himself in a shape of a flame, which is symbolic here as well.

I wish I had insightful commentary to contribute. Instead, I will acknowledge the best I can do is recognize and appreciate the depth and elegance of your presentation, promise to investigate it, and say once again, thank you. You are really stretching my mind here. Den

As always, you incorporate gorgeous art works. The Achilles shield here is extraordinary. Thank you.