How Bad Habits Become Our Destiny: Aristotle, Vice, and the Deformation of the Soul

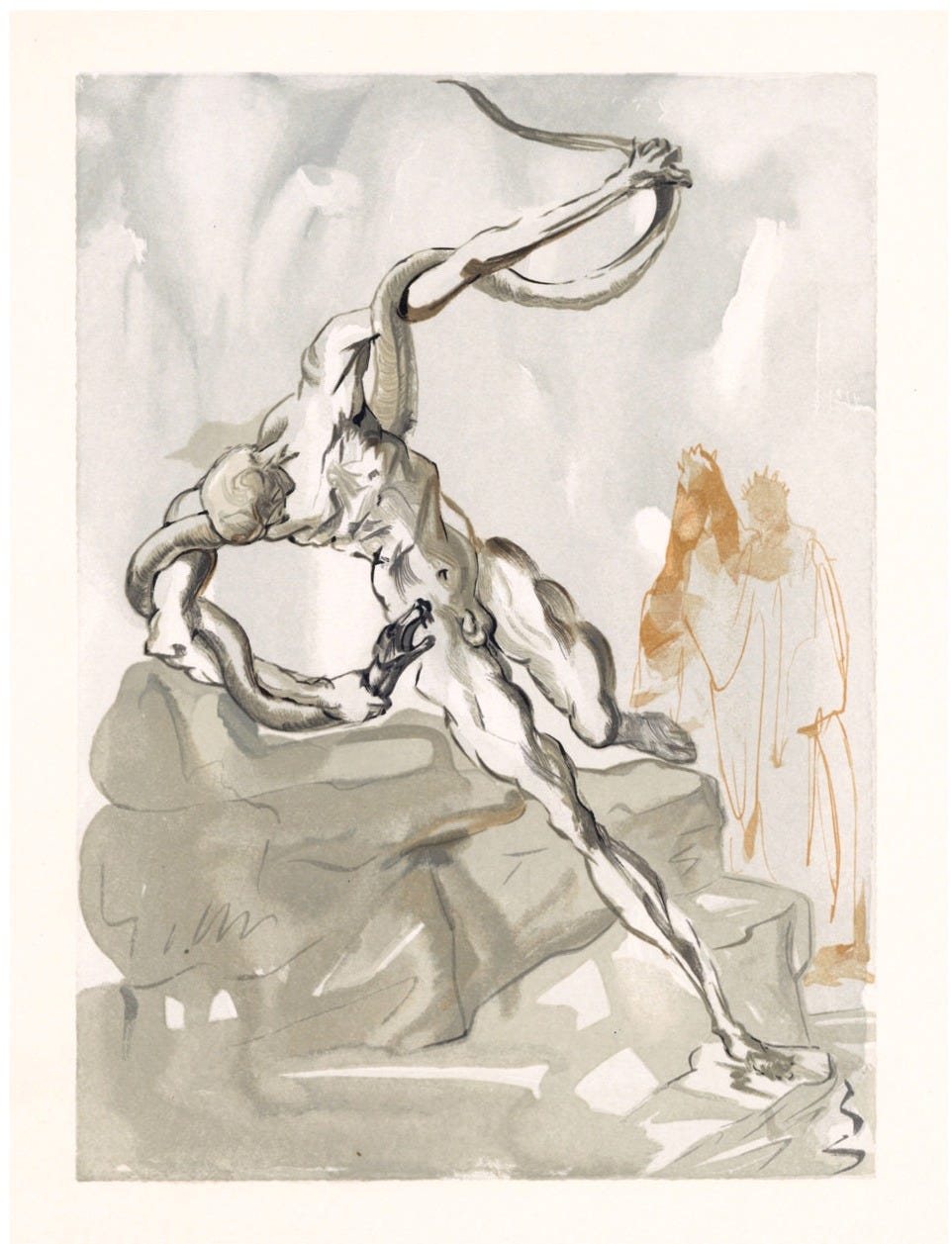

(Inferno, Canto XXV): Metamorphoses of Thieves, Vanni, Vice and Sin

I am compelled to speak of metamorphoses

~ Ovid

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

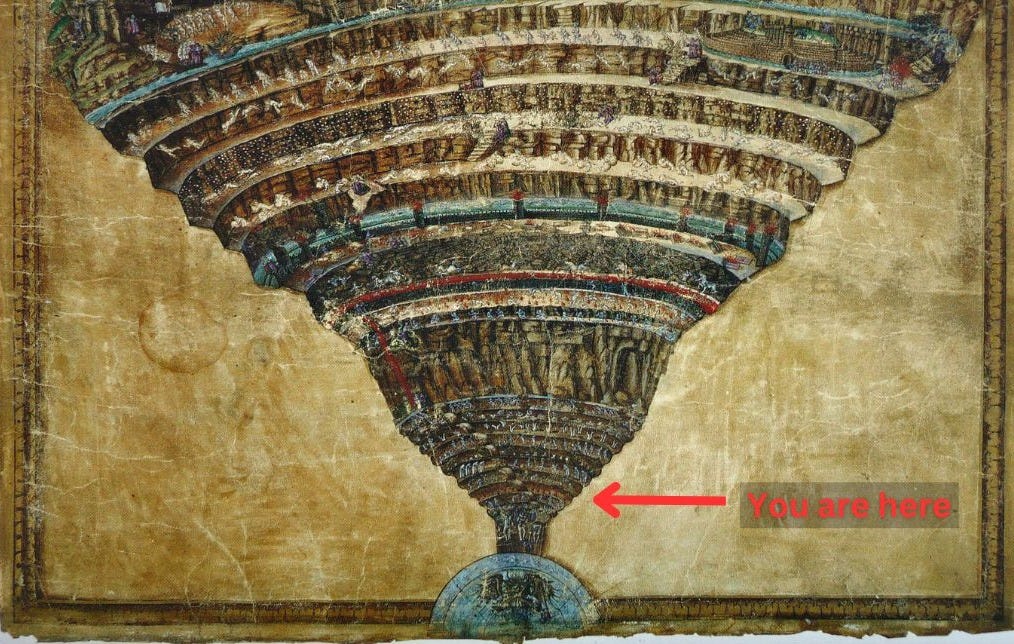

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Twenty-Fifth Canto we remain in the seventh bolgia of the Eighth Circle and encounter the transformation of Thief and serpent. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Eighth Circle, Seventh bolgia and the Thieves - Vanni Fucci curses God with obscene gestures - Cacus the Centaur - Dante and Virgil hear the Thieves below and watch - The transformations of serpents and men - Some blending, some exchanging forms - Only Puccio Sciancato is unchanged.

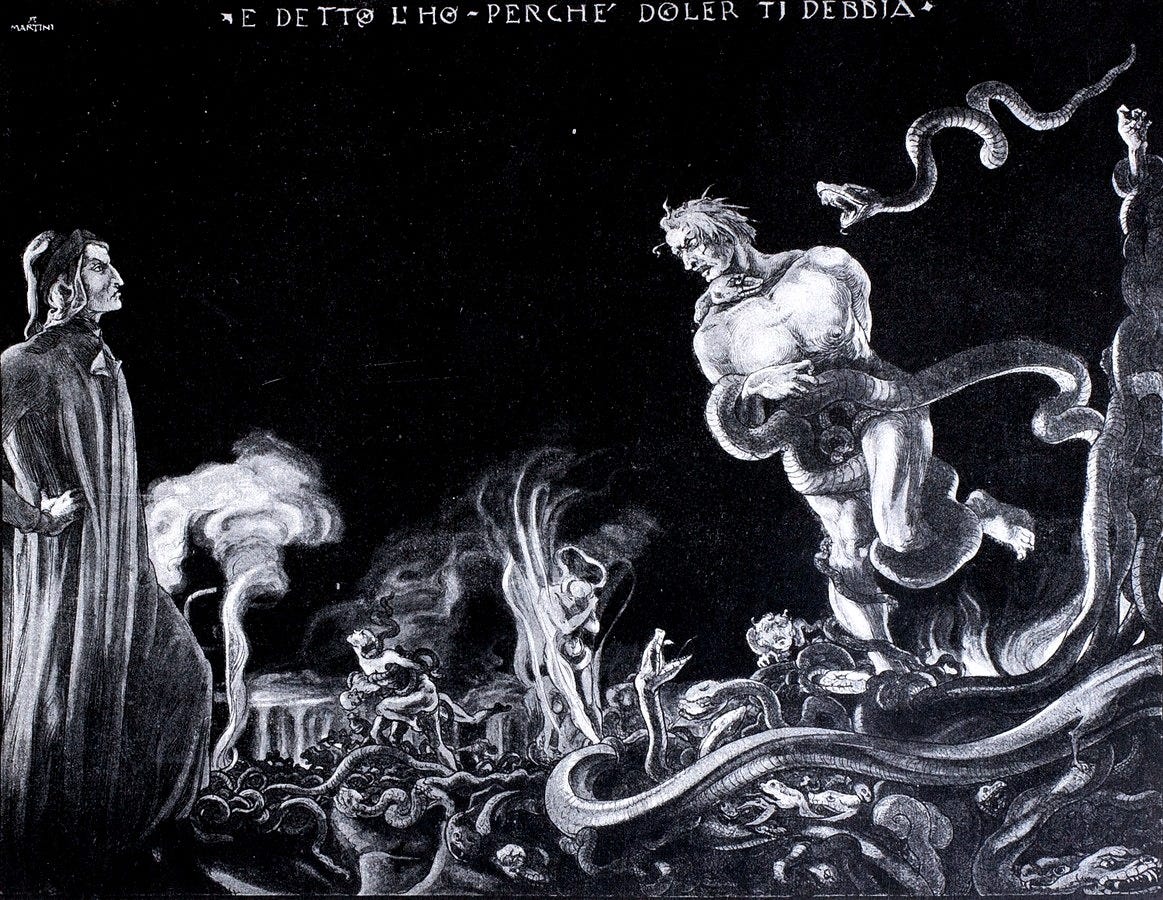

Vanni Fucci, the thief of sacred objects who prophesied the downfall of Dante’s White Guelph party at the end of Canto XXIV, opens the continued exploration of the seventh bolgia of the Eighth Circle with an obscene gesture,1 cursing God. The snakes, as though to silence him, coiled tightly round his neck and arms, stilling “his tongue and his arms so that he can no longer blaspheme God.”2

Pistoia, ah, pistoia, must you last:

Why not decree your self-incineration,

since you surpass your seed in wickedness?

XXV.10-12

Pistoia is the land of Vanni Fucci, the town near which Catiline and his army fell in battle in 63 BC after conspiring against Rome; the town itself was founded by those left from Catiline’s forces, and was named such because of the death and pestilence that permeated the area.

Upon the stronghold of Carmignano [near Pistoia] there was a tower seventy braccia high, and up there two marble arms that made the fiche toward Florence with their hands.3

Vanni was the haughtiest soul Dante had encountered yet: for his lack of repentance, for his theft of sacred church items, and finally for the obscene gesture with which he cursed God. Vanni was even haughtier than “he who fell from Theban walls”, referring to Capaneus, one of the Seven against Thebes,4 accused of Blasphemy, lying in the burning sand of the third ring of Circle Seven.

As Vanni fled, a galloping centaur appeared - who we will find is Cacus - crying out in anger seeking Vanni, “that bitter one” (18). The centaur’s back was covered in snakes just as the other sinners, more than the infamous snakes of Maremma, whose monastery was infested with snakes and uninhabitable. Not only snakes, but:

Upon his shoulders and behind his nape

there lay a dragon with its wings outstretched;

it sets ablaze all those it intercepts.

XXV.22-24

Virgil names this centaur as Cacus, whose brothers they had already met as the guardians of Phlegethon, the river of blood, of the first ring of the Seventh Circle. Cacus is here with the thieves because of the cunning nature of his crime; he is both guardian and being punished.

Hercules, for the tenth of his twelve Labors, had stolen the prized cattle of Geryon. Cacus in turn stole the cattle from Hercules. So that Hercules could not follow their hoofprints to find where or what direction they had gone, Cacus dragged them backwards into his cave, obscuring their hoofprints.

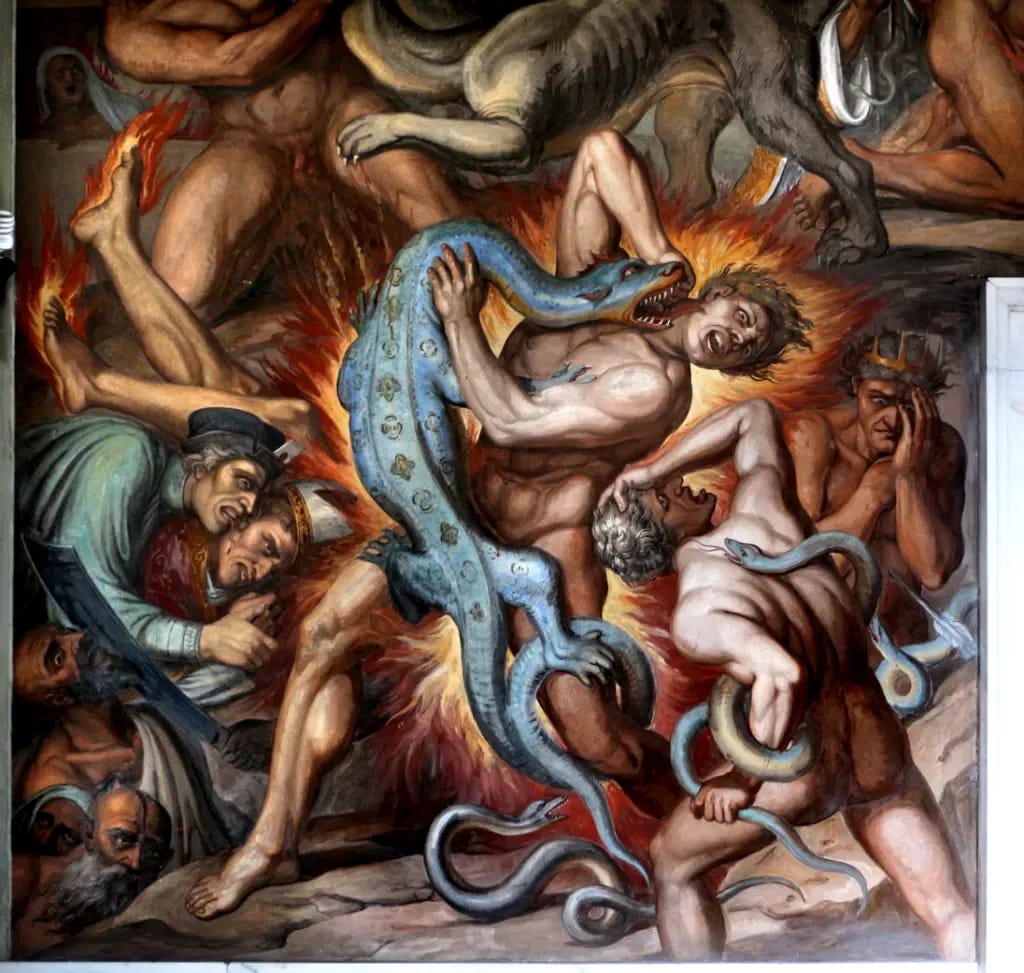

Cacus left as Virgil was explaining this to Dante. They heard three shades below them in the Seventh bolgia - still that of the Thieves - calling up to ask who Dante and Virgil were, standing there on the bank. These three, as we will find, are Agnello, Buoso and Puccio; it will be useful to keep each character straight as we move forward. But even as they asked, they also began asking each other where their companion Cianfa had gone - he had already undergone a transformation, but they do not know that yet. Dante signals Virgil to be silent, as they became spectators to the following scene.

Dante does not name most of the thieves until later in the Canto. As we move into the grotesque blending and transforming of serpent and human, their loss of identity - as explored in the falling into ash in the previous canto - is more pronounced. We will name the characters as we go here, as they can be hard to keep track of.

Agnello dei Brunelleschi: A Ghibelline of Florence, who “even as a boy…used to empty the purses of his father and mother; later, he would empty the strongbox in the ship and steal other things. Then, as an adult, he broke into other people’s houses. He would dress like a pauper and wear the beard of an old man. And for this reason, Dante has him transformed through the serpent’s bites, as he was when he stole.”5

Buoso degli Abati: He is of an uncertain identity, with little information to be found about him.

Puccio Galigai Sciancato: Also called Puccio the Lame. In the records of his history, “it is recounted that he committed beautiful and graceful thefts.”6

Cianfa dei Donati: A Florentine, “Cianfa was a knight of the Donati family, and was a great cattle thief. He broke into shops and emptied out the strongboxes.”7

Francesco Guercio dei Cavalcanti: A Florentine, he had been murdered by the residents of Gaville. His family retaliated back upon the town, killing many of their inhabitants, hence their grieving in the final line of this Canto.

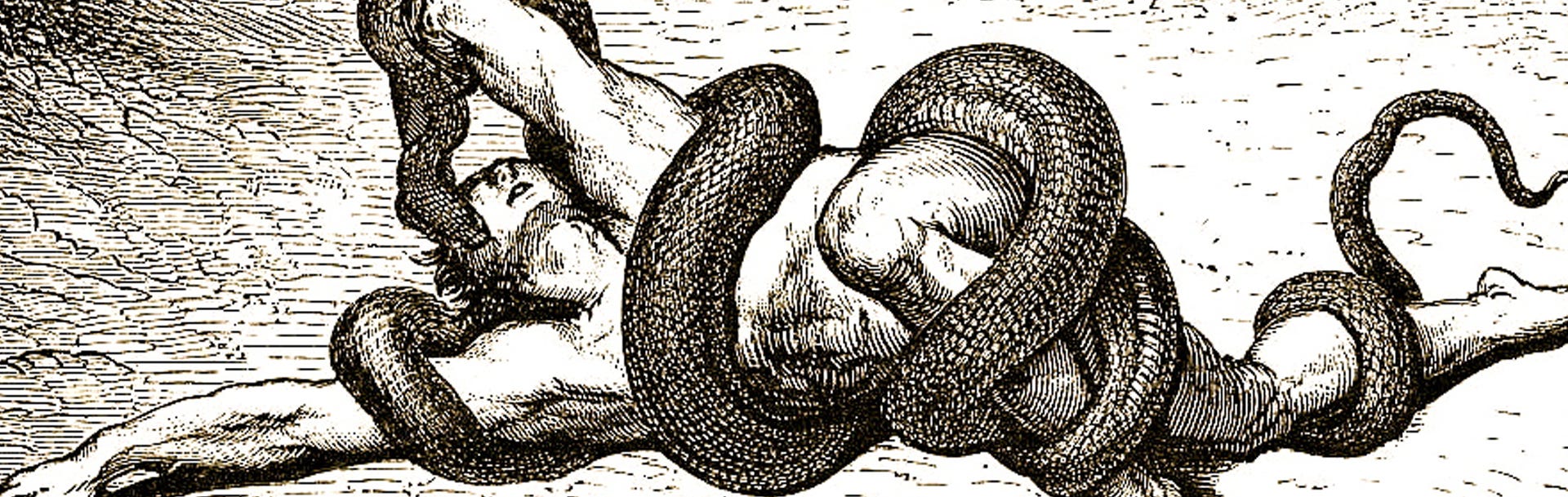

Before Dante begins explaining the transformations that he and Virgil witness, he mentions, that what he is about to relate is so unbelievable that he himself can hardly believe it. The first serpent to appear is really the missing Cianfa:

No ivy ever gripped a tree so fast

as when that horrifying monster clasped

and intertwined the other’s limb’s with its.

Then just as if their substance were warm wax,

they stuck together and they mixe their colors,

so neither seemed what he had been before.

XXV.58-63

This first transformation brings with it a disordered sense of blending; the fusion brings a melting of textures and bodies and colors slowly creeping into each other. The other two who are watching, Buoso and Puccio, call to the sinner (Agnello) being absorbed by the legged serpent (Cianfa). Once this grotesque transformation is complete, the new being, composed of Cianfi and Agnello, snuck slowly away. Another creature now comes into the picture:

Just as the lizard, when it darts from hedge

to hedge, beneath the dog day’s giant lash,

seems, if it cross one’s path, a lightning flash,

so seemed a blazing little serpent moving

against the bellies of the other two,

as black and livid as a peppercorn.

XXV.79-84

This “little serpent” is the fifth sinner we meet in this Canto, Francesco Guercio dei Cavalcante. He bit into Buoso’s navel in a violent manner. Buoso stared speechless and yawned, and from the serpent’s mouth and Buoso’s wound simultaneously came smoke and fumes, which began to mingle with each other.

Dante begs that Lucan and Ovid be silent on the imagery of metamorphoses so that Dante may report what he has seen, which is more fantastic than anything reported before.

Lucan we have seen before; he was the nephew of Seneca the Younger and wrote the Pharsalia about the Civil War between Caesar and Pompey. Here Dante is referring to two episodes within Lucan’s account in which his men are bitten by snakes and undergo graphic transformations which lead to their deaths. Nasidius, when bitten by a Prester, swelled and bloated until he burst,8 and Sabellus, who when bitten by a Sep had his flesh melt away into a formless mass.9

Ovid also has accounts of metamorphoses into snakes with the story of Cadmus, the founder of Thebes, who was transformed into a serpent for killing the favored serpent of Mars. Arethusa was a nymph who was transformed into the waters of a fountain;10 the blending of her waters with the waters of the river god Alpheus in the myth is similar to the serpent and human blending.

I do not envy him; he never did

transmute two natures, face to face, so that

both forms were ready to exchange their matter.

XXV.100-103

Both Buono, the wounded one, and Cavalcante, the one embodied in the serpent, will exchange into each other’s substance, and transform man to serpent and serpent to man. Their mutual transformation is detailed in lines 100-135, with a symmetry between the two; the serpent tail of one splitting while the legs of the other fused, ones skin grew soft while the other turned to scales, the arms of one receded while those of the other grow to a mans length, even the formation of the private parts and the hair on their heads growing or receding. Finally the faces transform, noses, ears and tongue, until the metamorphosis is complete. Buono, the beast, scurries away, while the newly formed human shade of Cavalcanti names Buono for the first time, and sees him run as he so recently had.

These are the transformations that Dante and Virgil stood as silent witness to, and he asks for pardon if his tale did not live up to the challenge of being more fantastic than those found in Lucan and Ovid.

Still with them is one of the original three thieves that they had heard talking at the beginning of the Canto, Puccio Sciancato. This is the one thief that we do not see transform. The other, who is referenced in the very last line of the Canto, is finally named as Cavalcante, the “little lizard” in line 83, who had turned into a man as Buono had turned into the beast. That Cavalcante had been murdered by the residents of Gaville, whose family retaliated back upon the town, killing many of their inhabitants, hence their grieving.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

The mediation by the serpent was necessary. Evil can seduce man, but cannot become man.

~ Franz Kafka

From that time on, those serpents were my friends,

for one of them coiled then around his neck,

as if to say, “I’ll have you speak no more”;(lines 4-6)

This canto feels like a Hieronymus Bosch triptych—mad metamorphoses, men turning into snakes, snakes turning into men; fusions, deformations, burnings, and endless transformations. I usually write these pieces in the evening, but for these scenes I had to turn my routine upside down, writing in the morning and flowing into the afternoon. One piece of advice every art lover will give you: never look too closely at anything created by the hand of Brueghel or Bosch right before bedtime.

A similar kind of advice applies to reading the following canto: do not gaze too long into the abyss filled with thieves — to paraphrase a certain German philosopher — or the abyss may find its way into your dreams.

It is not only the bodies of the damned that undergo metamorphosis, but Dante’s spiritual journey as well. Each of the previous cantos stood as separate entities, even when their themes and characters were connected— but not so with Cantos XXIV and XXV. If we pay close attention, we can notice that they have metamorphosed into a single, continuous whole.

“From that time on, those serpents were my friends.” Dante’s moral discernment, too, undergoes a kind of metamorphosis: the serpent of the Garden of Eden merges with the serpents of this bolgia, as the punishment of Vanni reveals to him the deeper meaning behind the Divine architecture of Inferno.

Even the voice of God is metamorphosed into a cruel and perverted echo of itself: after Vanni’s defiance of the Divine order, it is the enraged Centaur who shouts the same words that God once uttered when Adam, having transgressed His command, was called upon to reveal himself.

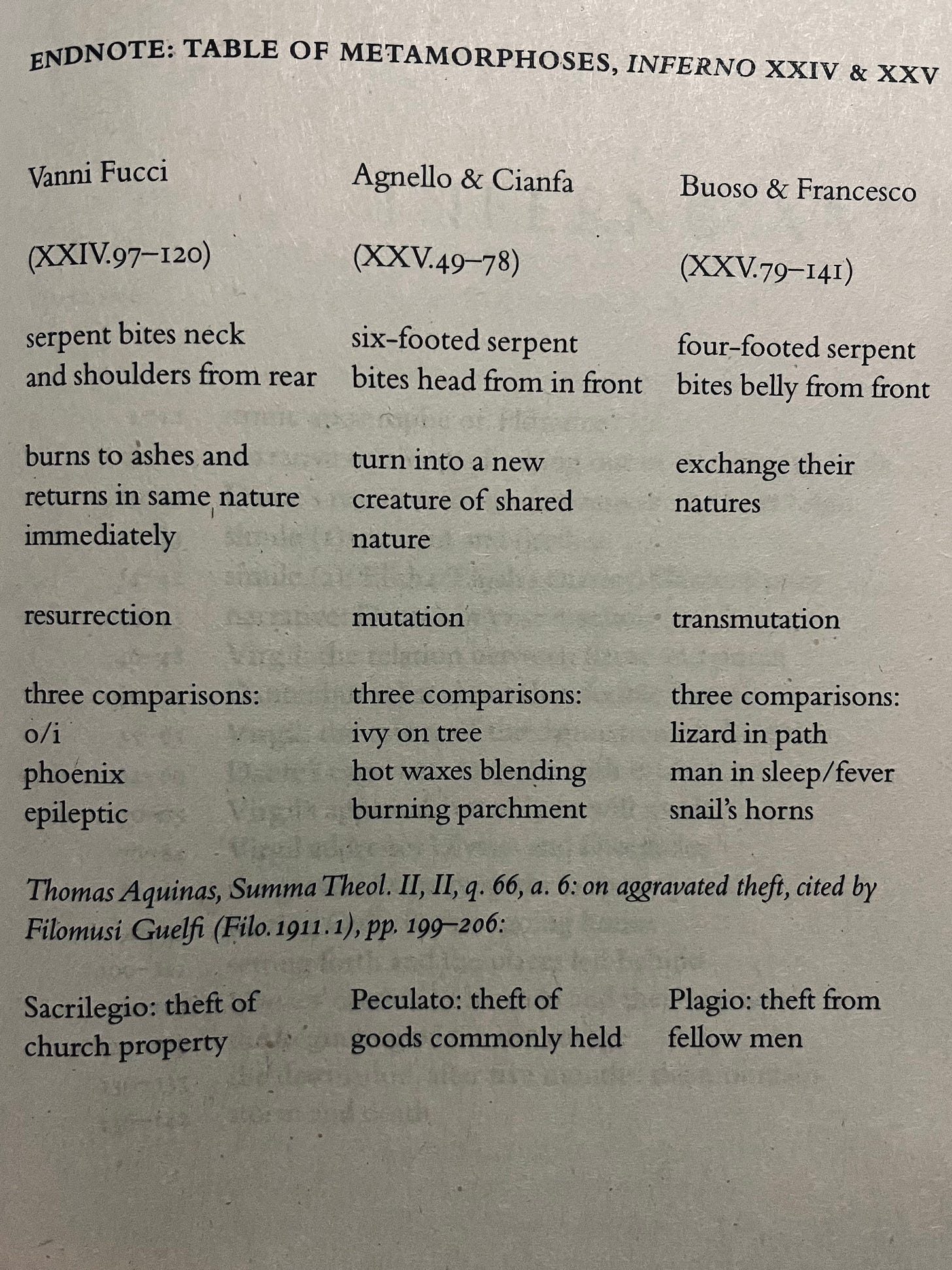

Dante is a great taxonomist of vice and virtue, and here—very much in the spirit of Aristotle—he distinguishes theft into three kinds: theft from the Church, theft from the common goods of the community, and theft from fellow men. (Ah, how I wish modern politicians, across all continents and cultures, would gaze into this abyss—so that this terrifying abyss might gaze back at them.)

I. What, in your opinion, is worse: vice or sin?

The places in Inferno are not reserved simply for those who have sinned (for all of us have done things we regret and feel remorseful about); they are reserved for those who have lived in vice.

“We are what we repeatedly do,” wrote Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics; to do good once, or by accident, does not make one virtuous — it is conscious and repeated effort that counts. Vanni, like every other damned soul we have met or will meet, was not merely a sinner — we all are sinners — but someone who lived in vice and loved it.

The difference between a sin (or, wrongdoing11) and vice is the same as the difference between lying and being a liar. Sinning can be an isolated event, whilst vice is a character trait.

Our thoughts become our habits, our habits become our character, and our character becomes our destiny. What we witness in the case of Vanni and the other thieves in this bolgia is how their character has metamorphosed into their very physical form—just as their life of vice was transformed into the theft of physical possessions.

… and of course, there is also Capaneus.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Capaneus and Vanni: Pride against God

There is an interesting parallel between Vanni’s blasphemy and that of Capaneus. Capaneus, whom we met in Canto XIV, was damned for his revolt and pride against God, while Vanni finds himself in a much lower place than Capaneus, for the sin of theft.

Vanni’s blasphemy against the Divine order is the consequence of his wicked nature, of a life steeped in vice. He is not in the same circle as Capaneus for precisely this reason: if Capaneus’s hatred of the Divine was driven by pride, Vanni’s defiance is fuelled by a character corrupted by vice and wrongdoing.

Vanni is bitten by serpents who inject into his dead veins their venom; Vanni’s character became his destiny since it is poisoned by his own vice.

Ripeness and Unripeness

My reader must have noticed that I am in love with the etymologies of words. We are reading poetry after all, and every word has its meaning and its meaning is often derived from its origins.

You might have noticed that the centaur Cacus, when he calls for Vanni, chooses the word ‘unripe’ (acerbo). Interestingly enough, as Hollander points out in his commentary, in Paradiso (XXVI), God refers to Adam before his transgression as ‘ripe’ (maturo).

If we pause to reflect, we see that Dante’s journey is, at its core, an exploration of what makes a soul ‘unripe’—and, ultimately, in Paradiso, he will discover, or rather have revealed to him, what it means to be ‘ripe’ or mature. This opens up for me a fascinating dimension of a subject I have been deeply curious about: what does it truly mean to be mature?

I see, both in many of the people around me and within myself, a certain kind of infantilism, a lack of true maturity. And yet, what precisely defines maturity, and how one reaches it, remains an open question for me.

Perhaps in Paradiso, once we have overcome all forms of immaturity, we will come to understand what it means to be mature in our psyche. Perhaps we must first be infants and children in order to grow into true maturity. After all, an apple is first unripe, and it takes time for it to mature into something ready to be enjoyed.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

When he had finished with his words, the thief

raised high his fists with both figs cocked and cried:

“Take that, o God; I square them off for you!”From that time on, those serpents were my friends,

for one of them coiled then around his neck,

as if to say, “I’ll have you speak no more”;another wound about his arms and bound him

again and wrapped itself in front so firmly,

he could not even make them budge an inch.Pistoia, ah, Pistoia, must you last:

why not decree your self-incineration,

since you surpass your seed in wickedness?

Characters:

- Cacus - Dante turns the monster of myth, son of the god Vulcan and the gorgon Medusa, into a centaur. In myth, Cacus was a monster who lived under one of the seven hills of Rome, the Aventine hill, from which he terrorized the land around, murdering and devouring, soaking the earth with blood. The dragon that Dante places on his shoulders and neck that breathes fire could be replacing the monster Cacus’ fire breathing abilities.

Virgil says of Cacus:

Hiding within it, where rays of the sun couldn’t enter, the fearsome

Visage of subhuman Cacus. The groundsoil was warmed into humus

Constantly freshened with slaughter; and nailed with pride at the entrance

Hung human heads, each face decomposing grimly to greyness.

Vulcan had fathered this monster. So his were the fires that the beast’s face

Vomited dark from its mouth as it set its immense mass in motion

Virgil Aeneid VIII.194-199

“Herakles paused to pasture his cattle near Cacus’s lair. The monster spotted the splendid beasts, and while Herakles slept he slyly stole eight of them, four bulls and four cows, dragging them back to his cave by their tails so as to leave no hoof prints pointing towards their place of concealment…never before had anyone seen Cacus afraid, never before had there been terror in his eyes”12 until he came face to face with Hercules, who killed him in less than ten blows.

- Sabellus -

But death more grim

than that was in full view: a tiny Seps was fastened to

the leg of miserable Sabellus; as it clung with cunning fang

he tore it off and with his javelin pinned it to the sands.

It is a serpent small in size, but so much bloody death

no other brings. For the skin nearest to the wound

burst, shrank back, uncovered pale-coloured bones;

and now as the cavity gapes, the wound is bare without a body;

the limbs are drenched with pus, the calves have melted, the knee

was bare of covering, and even every muscle of the thighs

dissolves, and the groin drips with black decay.

The membrane which binds the belly burst apart, and out melt

the entrails; and not as much as there should be from an entire body

melts into the ground, but the savage poison boils

the limbs down; death shrinks the whole into a tiny pool of venom.

Lucan, Pharsalia IX.762-778

- Nasidius -

Nasidius, a farmer of the Marsian land, a scorching

Prester struck. A fiery redness set alight his face,

and swelling strains the skin, confounding all his features,

their shape destroyed; now larger than his entire body

and exceeding human size, the pus is exuded over all

his limbs as the poison exerts its power far and wide;

the man himself is out of sight, buried deep in bloated body,

and his breast-plate cannot hold the swelling of his bursting chest.

Not so does the foaming mass of water overflow

from a blazing cauldron; sails in the Corus curve

into bellies not as vast. No longer can the shapeless mass

and torso with its jumbled bulk contain the swollen limbs.

Lucan, Pharsalia IX.790-801

- Cadmus -

And Cadmus said 'Was that a sacred snake

My spear transfixed when I had made my way

From Sidon's walls and scattered on the soil

The serpent's teeth, those seeds of magic power?

If it is he the jealous gods avenge

With wrath so surely aimed, I pray that I

May be a snake and stretch along the ground.'

Even as he spoke he was a snake that stretched

Along the ground. Over his coarsened skin

He felt scales form and bluish markings spot

His blackened body. Prone upon his breast

He fell; his legs were joined, and gradually

They tapered to a long smooth pointed tail.

He still had arms; the arms he had he stretched,

And, as his tears poured down still human cheeks,

'Come, darling wife!' he cried, 'my poor, poor wife!

Touch me, while something still is left of me,

And take my hand while there's a hand to take,

Before the whole of me becomes a snake.'

More he had meant to say, but suddenly

His tongue was split in two; words failed his will;

And every time he struggled to protest,

He hissed; that was the voice that nature left.|

Ovid Metamorphoses IV.570-592

- Arethusa -

Oh! poor wretched me!

What heart had I! Was I not like a lamb

That hears the wolves howling around the fold,

Or like a hare that, hiding in the brake,

Sees the hounds' deadly jaws and dares not stir?

Alpheus waited; at that place he saw

My footprints stopped; he watched the cloud, the place.

Trapped and besieged! A cold and drenching sweat

Broke out and rivulets of silvery drops

Poured from my body; where I moved my foot,

A trickle spread; a stream fell from my hair;

And sooner than I now can tell the tale

I turned to water. But the river knew

That water, knew his love, and changed again,

His human form discarding, and resumed

His watery self to join his stream with me.

Diana cleft the earth. I, sinking down,

Borne through blind caverns reached Ortygia,

That bears my goddess' name, the isle I love,

That first restored me to the air above.'

Ovid, Metamorphoses V.622-641

le fiche: a fist with the thumb placed between the index and middle fingers.

Singleton, Commentary on the Inferno 429

Singleton 428

Inferno XIV.46-72

Singleton 437

Singleton 446

Singleton 435

Pharsalia IX.790-801

Pharsalia IX.762-778

Metamorphoses V.622-641

I use sin and wrongdoing interchangeably. Sin implies a violation of the moral code prescribed by Divine authority, while wrongdoing is its secular counterpart, rooted in philosophy. The two often coincide, as in the case of theft, which is condemned both in scripture and in classical philosophy.

March, Penguin Book of Classical Myth 204

"The difference between a sin (or, wrongdoing11) and vice is the same as the difference between lying and being a liar. Sinning can be an isolated event, whilst vice is a character trait."

Short and precise summation. Again, so much in each of your presentations. Better than a college course. You are providing a great service here. Thank you. Den

I'm struck by the resemblance between Aeneas' descent into Hades and Dante's descent into hell....