How Gluttony Destroys Our Cities (Dante Read-Along)

(Inferno, Canto VI): Third Circle: Gluttony, Ciacco and the Fate of Florence

The flesh endures the storms of the present alone; the mind, those of the past and future as well as the present.

Gluttony is a lust of the mind.

~ Attributed to Thomas Hobbes

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this sixth Canto we find ourselves in Third Circle of Gluttons. You can find the main page of the read-long right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character and symbolism explanations.

All wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

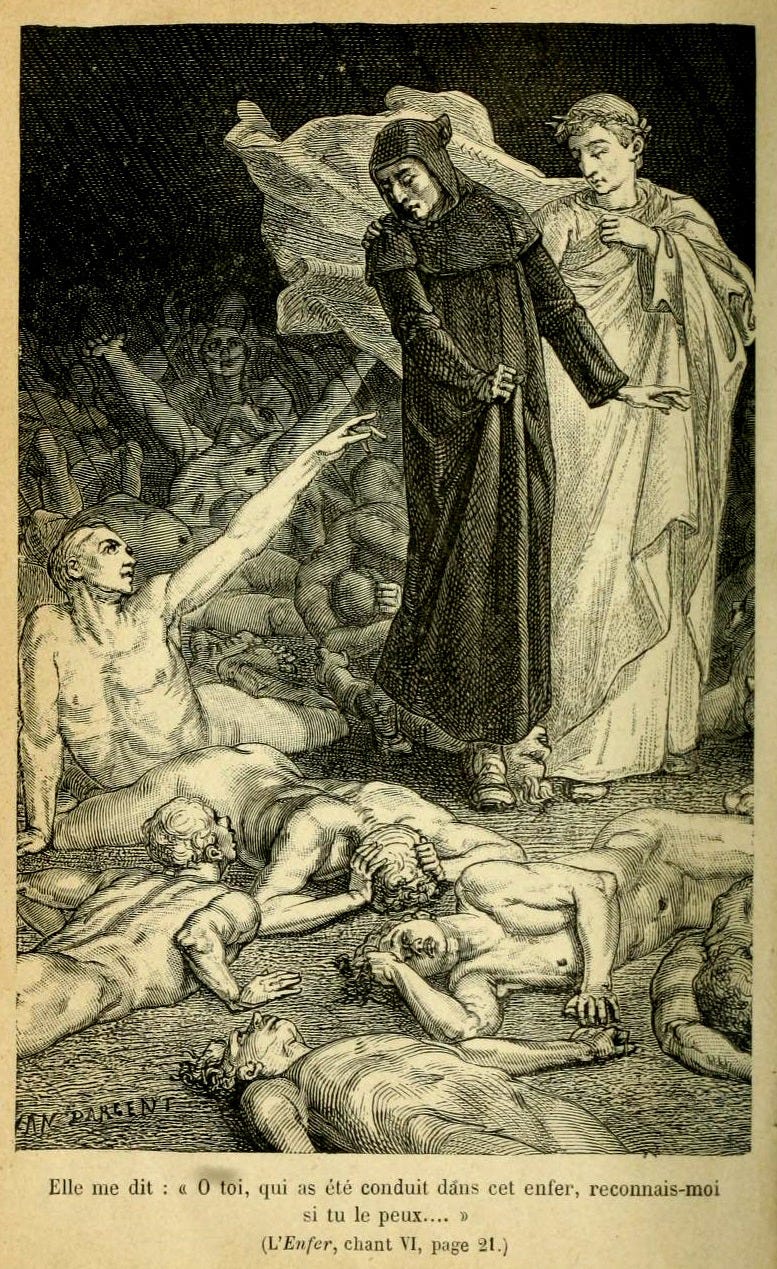

Dante awakens in the Third Circle of the Gluttons - The sufferers wallow in a cold and filthy marsh, pelleted by rain and snow - Cerberus, the Guardian of the Underworld is pacified - Dante speaks with Ciacco, an acquaintance from Florence - A prediction of the workings of Florentine politics - Dante and Virgil discuss the Last Judgement.

Canto VI: Summary

Dante awakens from the swoon he suffered upon hearing the story of Francesca and Paolo in the realm of the Lustful, and not only awakens, but has found himself in the Third Circle, surrounded by suffering on every side. Charles Singleton, in his commentary, takes note of the times in the Inferno that Dante awakens or appears in a new setting without mention of how he had gotten there, such as in Canto IV when they cross the Acheron. This is another of those moments.1

Again we see the scene described before we learn of who is in this circle. The atmosphere is that of a terrible cold and dirty rain, hail and snow, and the ground beneath sends up an awful odor - in that marsh the sinners wallow in the cold and filthy stench.

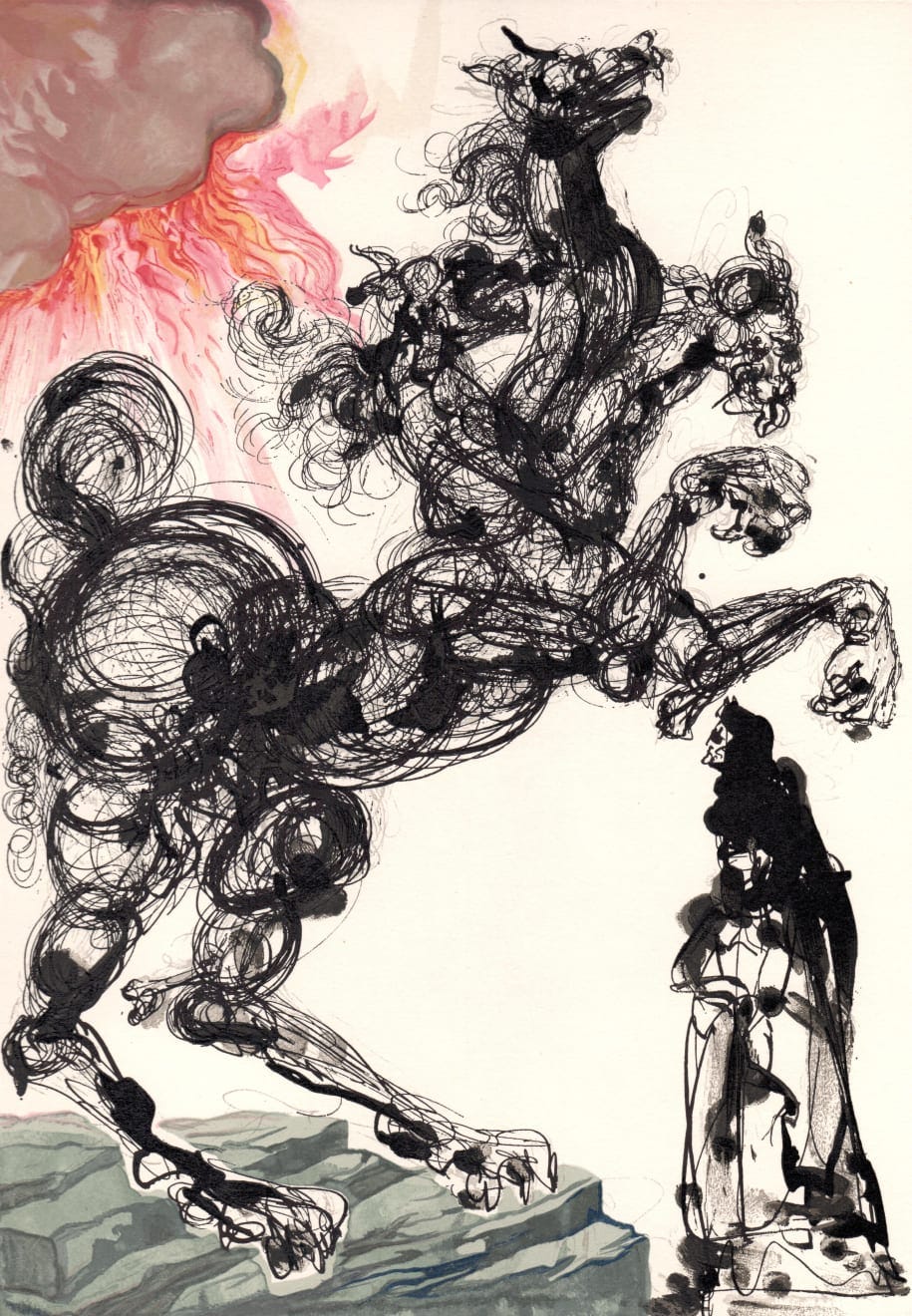

We meet Cerberus, the three headed dog who guards the entrance to the Underworld, giving “admittance to all and escape to none.”2 Yet Dante describes the dog with almost human qualities, with his greasy beard and hands like claws, monstrous in his actions and aspect. In the Italian, Dante calls Cerberus a “worm,” hearkening back to a biblical reference symbolizing decay; Cerberus is standing “in the midst of so much putrefaction.”3 “Worm” is also used in other literature to signify a dragon.

Cerberus has been noted, in early accounts, to not only guard the doors of the Underworld, but to be a literal devourer of the dead, creating a fitting guardian to this level of the Gluttons.

While in the Aeneid Cerberus had to be put to sleep with a drugged sop thrown by the Sibyl so that they could enter, Dante’s Cerberus is satisfied with the earth that Virgil throws him to quiet him. There is a blessed silence as Cerberus of the Inferno feeds - imagine the cacophony of sinners being punished and Cerberus howling.

As Dante and Virgil step over the shades - the form of which they see, but which have no substantiality - one sat up from the marshy mess to speak to them, and asks if Dante remembers him.

We walked across the shades on whom there thuds

that heavy rain, and set our soles upon

their empty images that seem like persons

Inferno VI.34-36

Dante does not recognize the figure, who identifies himself as Ciacco (which in Italian is a derogatory term for “pig”), and we learn that he is in Hell for the sin of Gluttony.

Gluttony is disordered Appetite. Think of the difference between a natural appetite that can be fulfilled and satisfied, as opposed to this cloying and terrible craving, a craving that is not subdued by being filled nor can be abstained through reason. The disorder of this craving is that what should be filled by God, is attempted to be filled by that which cannot satisfy. Note also the change of the lustful craving of Canto IV in which “mutual indulgence” is refined into the “solitary self-indulgence” of Gluttony; there is a wretched solitude to their offense.

Thomas Aquinas speaks in his Summa of this disordered appetite: he first points out that is creates a “dullness of sense in the understanding”, and further, it is “disorderly in many ways by immoderation in eating and drinking, as though reason were fast asleep at the helm.”4

Dante asks Ciacco if he knows what will become of Florence, which in Dante’s time was divided by the political conflict between the Guelfs and the Ghibellines. Ciacco gives a prophecy about the future of Florentine politics. The “party of the woods” is the White faction of the Guelphs, “the other” is the Black faction of the Guelphs, who are struggling for power. Dante is in exile due to these events.5

Ciacco gives his prophecy of Florence (VI.60-75), and Dante asks if “there are any just men there” (VI.62), hearkening back to biblical references of Abraham and the destruction of Sodom, which God promised he would not destroy if any just men could be found.

Dante asks for more information about other figures, such as Tegghiaio, Farinata, Arrigo, Mosca, and Jocopo Rusticucci. These he says, were on the side of good, and is almost afraid to learn if they are below in Hell, or if they are above in Heaven. But Ciacco tells Dante that other sins have put them all further below him in Hell.

After these prophecies and information, Ciacco begs Dante to remember him to their acquaintances back in Florence:

But when you have returned to the sweet world,

I pray, recall me to men’s memory:

I say no more to you, answer no more.

Inferno VI. 88-90

He then returns to the mire; the “twisted and awry”, or cross-eyed gaze that he gave them as he sunk into the mire was indicative of the glutton.

As Ciacco sinks away, Virgil introduces the concept of the biblical Last Judgement, when “the angel’s trumpet will sound and each soul will return to its tomb,”6 referring to the second coming of Christ, during which all the dead will rise and regain their bodies. Christ - who is never named directly in Hell - is the “hostile judge” (VI.96).

Virgil and Dante walk from this scene talking more of these ideas and what will become of those in Hell upon the second coming of Christ. Dante asks:

And after the great sentence -

O master - will these torments grow, or else

be less, or will they be just as intense?

Inferno VI. 103-105

The “great sentence” here is referring to this Last Judgement. Virgil tells Dante that after this sentence, their pains in Hell will grow even greater. He calls Dante to remember “your science” (VI.106), which is based in Aristotle and the concept of the perfection of the uniting of soul with body.

As the Canto ends, they took a downward slope and met “Plutus, the great enemy” (VI.115), whom we will discover as another guardian in Canto VII.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

The glutton is much more than an animal and much less than a man.

~ Honoré de Balzac

There are vices that consume the individual, dragging them to their ruin, and there are vices so widespread and insidious that they topple cities, unravel states, and bring entire civilisations to their knees; for when enough hands feed the flame, the blaze spares nothing. Such is the nature of gluttony, a vice of excess that consumes both the soul and the fabric of society—thus it is here, in the third circle of Hell, that we first hear of Florence, a city already burdened by its own indulgence.

It is hard not to perceive gluttony as a kindred vice to the lust we encountered in the previous circle. Lust ensnares the soul, while gluttony weighs down the flesh—but both reveal the peril of desires unbridled.

I. Gluttony and Self-Respect

When Aeneas and his guide, the Sibyl, encounter Cerberus in the underworld, she subdues the beast by exploiting its greed, offering a lump of drugged food to silence it. Here, we witness a similar stratagem as Virgil pacifies Cerberus by hurling a handful of muddy earth, distracting the creature with its base instincts.

Such is the nature of overconsumption: it dulls the palate, erases discernment, and renders one indifferent to what they devour. Cerberus embodies this vice, unable to distinguish whether what it consumes is nourishing, pleasant, or even food at all. Its reason is enslaved to an insatiable lust for consumption.

If someone would offer us ‘muddy earth’, no matter how hungry we are, we would reject it. We respect our body and therefore we are not going to put in it whatever we are offered, in contrast to Cerberus whose gluttony made him lose all sense of self-respect and therefore he is fully satisfied with ‘muddy earth’.

It was Cicero who wrote that we need ‘self-respect to counteract base pleasures’.7 The shadow of Cerberus looms over us all in this age of overconsumption and indulgent ease—an age where, for the first time in history, excess claims more lives through obesity than scarcity through starvation8. To steer clear of this ruinous path, we must cultivate self-respect, for only a soul that esteems itself can master its desires and rise above its appetites.

II. Sin and Time

We walked across the shades on whom there thuds

that heavy rain, and set our soles upon

their empty images that seem like persons.

The nature of gluttony is such that it shrouds our vision, severing our grasp on both past and future. It enslaves the mind to the urgency of present cravings, leaving no room for reflection or foresight. I avoid bringing examples from our modern way of living, somehow I think that it might cheapen the genius of Dante, but our modern times are notorious for overconsumption, impatience, intemperance. All these vices arise from the cravings of the body, which knows only the present, blind to both memory and foresight, seeking only immediate gratification without regard for what was or what is to come.

III. City as a Body

Poetry is made of words and the origins of words reveal to us the true meaning behind the poet’s vision. The word ‘corpo’ in Latin translates as ‘body’, therefore the word ‘corporation’ is a combination of bodies. For the thinkers of the classical past there was a strong link between body and the city. As professor Giuseppe Mezzanota says in his famous lectures on Dante:

…look, the city's really like a body. When you have a body the hands work.

Yes, it seems that the mouth enjoys and savours the great pleasures of foods and so on. It seems that the stomach can be full, but actually whatever they produce and take in and they ingest, they redistribute to the body, to the rest of the body, to the hands, the feet, etc. The city is like a body. That's the analogy. Between the corporate structure of the city, the idea that the city is a corporation…

This is how Dante sees Florence, the city from which he was exiled - it is a body that became blind by its gluttony.

It is interesting also how he begins this canto. It begins with Dante ‘reviving his mind,’ having once again lost his senses after hearing the sorrowful tale of Paolo and Francesca. The phrase “Al tornar de la mente”—“upon reviving my mind”—reveals more than mere recovery. The Latin root of mente traces back to mensura, meaning “measure,” suggesting that the true function of the mind is to weigh, to discern, and to bring order to the reality that surrounds us.

This is when we meet Ciacco who consumed without measure, a man whose shade is so tormented by the heavy scorching rain, that Dante cannot recognise him.

What do we know about Ciacco? Was he a real man? Bocaccio in his Decameron describes Ciacco as "the most gluttonous fellow that ever lived.” In Tuscan ‘ciacco’ was a noun that meant “pig” and Hollander mentions that Ciacco was a Florentine banker who ate and drank so much that his eyesight went bad - as a result he could not count money and people made fun of him.9

We will meet plenty of ambiguous characters on our journey, and if Paolo and Francesca told us about their private life, Ciacco tells us little about himself and plenty about Florence’s public life. Florence, like the body of Ciacco, became blind by its gluttonousness.

Three sparks that set on fire every heart

are envy, pride, and avariciousness.

After reading this, one cannot help but wonder—if, like Dante, we were to encounter our own city in Hell, what form would its body take?

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Themes 🖼️ :

Language

The language Dante employs in the previous canto, particularly in Francesca’s speech, is soft and beguiling, woven with a charm that lulls the soul, much like the very passions that led to her ruin. The rhetorical style of the gluttons however is deliberately ugly. Even if you don’t speak Italian try to read this out loud and feel how it sounds:

Li occhi ha vermigli, la barba unta e atra,

e ’l ventre largo, e unghiate le mani;

graffia li spirti ed iscoia ed isquatra.

Two men are just.

Ciacco’s words recall the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, where not a single righteous soul could be found to save the city. By declaring that “only two men are just,” he underscores the depth of Florence’s corruption.

The Names of Sinners

“O you who are conducted through this Hell,”

he said to me, “recall me, if you can;

for you, before I was unmade, were made.”

Throughout our journey, Dante will encounter many sinners, both in Inferno and Purgatorio, and among them, countless souls will cling to an insatiable longing—to have their names remembered, to be called back into the world of the living.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

And he to me: “Remember now your science,

which says that when a thing has more perfection,

so much the greater is its pain or pleasure.Though these accursed sinners never shall

attain the true perfection, yet they can

expect to be more perfect then than now.”

Characters:

- Cerberus - In Dante represented by the epitome of Appetite, Cerberus is the three headed dog that guards the entrance to Underworld that figures in a number of Greek and Roman myths, including Homer and Virgil and the 12 Labors of Hercules.

- Ciacco - Dante encounters Ciacco in the third level of Hell, that of the Gluttons. Scholars agree that this is a difficult figure to pin down, and may be Ciacco dell’Anguillaia from Florence, Dante’s home town.

- Plutus - The god of wealth in Greek antiquity, he is the guardian of the Fourth Circle that we will meet in Canto VII.

Singleton Commentary on Inferno, p.96

Mark Musa VI.13-22.n

Singleton, p. 98

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, II-II.148.a.6

Dante was invested deeply in Florentine politics. As Boccaccio would tell us, Dante was so wise and beloved that he would have made a most notable ruler, except that the Guelfs-the party he sided with-were driven out. Much has been written of the Guelfs and the Ghibellines, the two sides of a Florentine blood feud, and the further Guelf factions of the Whites and the Blacks, and anyone interested in the political climate of Dante’s day will find many rich studies outlining it.

Within the Guelfs, there was a party split between the Cerci family (the Whites), and the Donati family (the Blacks). Dante was invested with the White’s, but his wife’s family was a Black, she being of the Donati family.

While Dante was with an envoy of the Whites who planned a meeting with the Pope, the disgraced Blacks took control, and Dante was sent into exile in 1301 on charges of “fraud and corruption while in office.” By the terms of his exile, if he returned, he would be burned to death as punishment.

Singleton, p. 105

Cicero, How to Grieve, p.51 (It is worth noting that this work is inspired by Cicero and its attribution is a subject of a debate among the scholars.)

I try to avoid contemporary examples in my writing, but the recent data by the WHO shows that 2.8 million people die each year as the result of obesity, while the most recent data shows that starvation took lives of 251,000 (2019) worldwide. Both numbers are horrifying, but the contrast between them shows the state of our societies regarding gluttony,

Hollander, Inferno, page 125

So much to ponder in Canto VI.

One fascinating aspect of Dante’s political thinking is how it’s driven by civil strife. He was a participant and victim — as is anyone subject to the poisonous brew of “envy, pride and avariciousness.” The Alexandrian historian Appian said about the Roman Civil Wars: “It is a story worth the attention of any who wish to contemplate limitless human ambition, terrible lust for power, indefatigable patience, and evil in ten thousands shapes.” Dante had rich inspiration for his “ten thousand evil shapes,” and the political commentary in the Divine Comedy, given the unnatural, irrational, sinful, wicked and devilish political strife of Florence. The city, beset by civil strife, is reproducing the selva obscura (dark wood) Dante first tried to elude.

The parallel between Dante and John Milton (“Paradise Lost”) is striking. Both lived in turbulent times (Dante and the *cosmic-level* disorder of Florence), and Milton during the English Civil War. They were both personally invested — and lost so much. As a result, both their works reflect an intense examination of issues such as justice, authority, divine order, righteousness, betrayal, alienation, and disillusionment. Dante is much more explicit in castigating transgressors than Milton’s oblique approach, but both take a hammer to instigators that revel in human disorder over divine order. The contrast is profound — Florence, as Augustine’s City of Man, with its factions and fratricide and systematic organization of hatreds, or his Civitas Dei, the City of God, heavenly, eternal, and rooted in divine love.

Ciacco’s “Dispatches from the future” set the despairing tone for this Canto, and that tone is amplified by the cacophony surrounding the pilgrim — the relentless frenzy and incoherent clamor — in contrast to Francesca’s sighing lilt in Canto V. In V we learned about the disruptive quality of desire — and now it’s magnified in the insatiable appetite of gluttony. The choice is stark — be consumed by mindless desire, be devoured by glutinous beasts, or partake of the ultimate banquet: Jesus giving the bread and wine to His disciples: “This is my body…this is my blood…”

To the question of what form our own city in Hell would take: The comedian in me says the “Department of Motor Vehicles,” but the historian says Saint Augustine’s Hippo, on the edge of chaos: ““When the Vandals were hammering at the gates of Hippo, Augustine’s city, the groans of the dying defenders on the wall mingled with the roar of the spectators in the circus, more concerned with their daily entertainment than with even their ultimate personal safety.” (Lewis Mumford, “The History of the City,” 1961)

Four short observations (I’m hoping for bonus points):

Cerberus: Dog, or “doglike?” Most importantly, its three-headedness foreshadows the three-headed Lucifer — both are anti-Trinitarian monsters devouring humans.

The “City as a Body” brings the Fable of Menenius to mind.

The “two men” — have variously been interpreted as historical figures, as symbolizing the moral and political decay of the city (“best we can do is two”), or as justice and righteousness.

The fate of the Florence elites illustrates the distance between the human perspective (the Pilgrim’s) and the judgment we make as humans, and the divine judgment on the dealings and doings of famous people — the discrepancy between their “reputation” on earth where they are judged one way, and then the real and final judgment of worth and value.

I’ll crosspost this to the thread, too.

There is, as always, a surfeit of brilliant commentary and helpful information here. I agree, too, that it is good to be careful about engaging in what historians call “presentism,” and I want to offer a cautionary note on the issue of obesity.

There is a wealth of information available to demonstrate that the causes of obesity in the US, where I live, are much more subtle and multi-dimensional than personal gluttony can possibly encompass. For example, studies like this one show a high correlation of obesity with poverty: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3198075/#:~:text=In%20contrast%20to%20international%20trends,145%25%20greater%20than%20wealthy%20counties.

If we ascribe obesity to gluttony, we are in danger of blaming individuals for circumstances not in their control. As this article notes in conclusion: “Halting U.S. diabesity epidemic and curtailing its health cost may necessitate addressing poverty.” The gluttons in wealthy countries like the US are not the poor, but wealthier individuals who have no concern for or willingness to address the plight of the poor.