How Sin Built the Renaissance (and the Beautiful Face of Deception)

(Inferno, Canto XVII): Geryon, Scrovegni Chapel and Phaeton

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

~ W.B. Yeats, The Second Coming

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

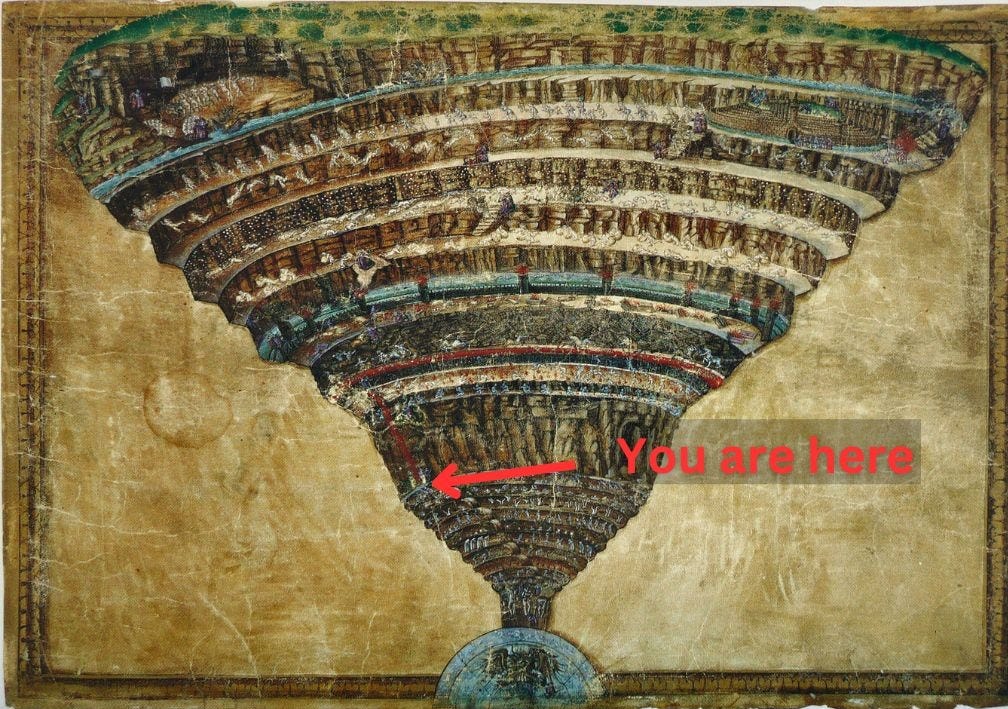

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Seventeenth Canto we encounter the beast Geryon and meet the Usurers in the burning sands. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

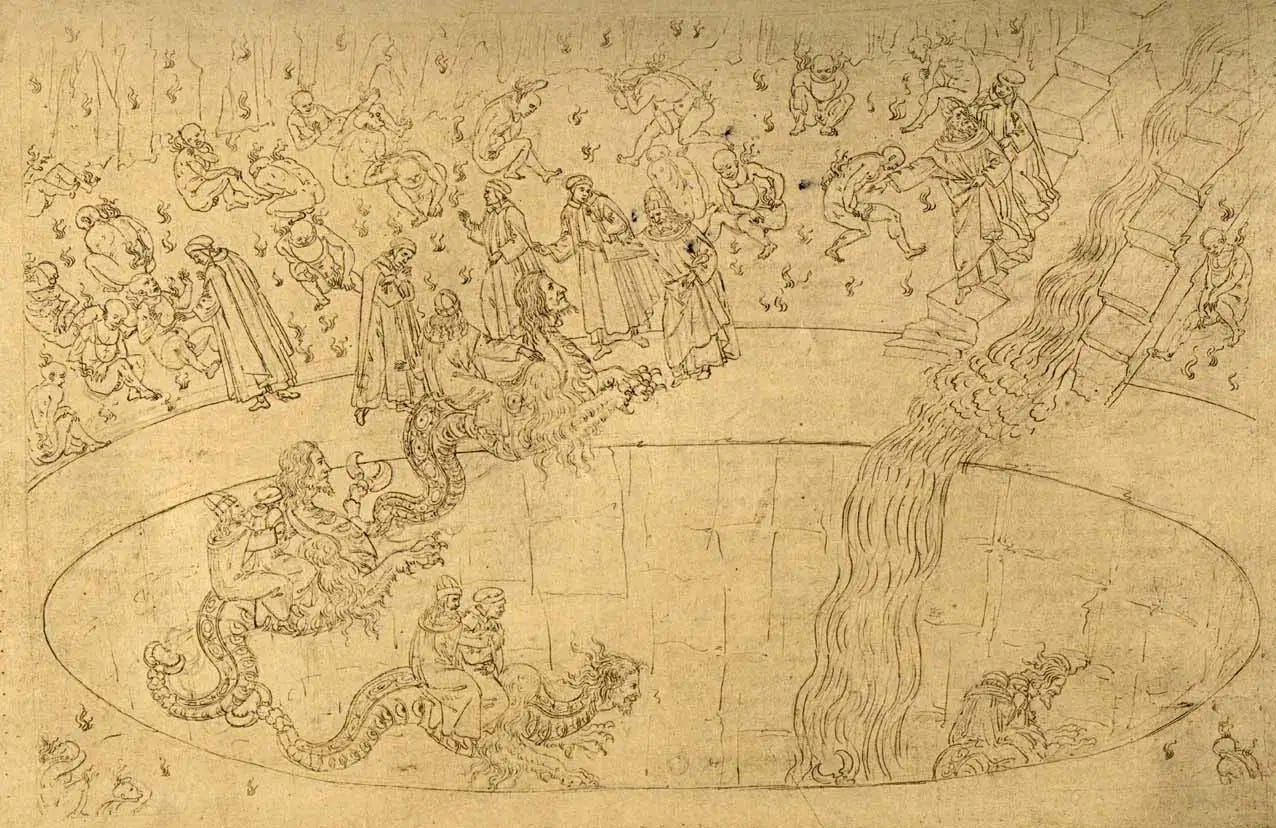

The Beast Geryon - The Third ring of the Seventh Circle of Violence - The Violent against Nature and Art - Usurers sitting in the burning sands - The pouches of the Usurers and the family emblems - Dante and Virgil climb the back of Geryon - He flies slowly down into the abyss - They land in the Eighth Circle of Fraud.

Canto XVII: Summary

As the burning sands of the third ring of the Seventh Circle continue, the Violent against Nature and Art, Virgil begins with a warning to Dante regarding the creature that had begun to swim up from the depths in Canto XVI.

Behold the beast who bears the pointed tail,

who crosses mountains, shatters weapons, walls!

behold the one whose stench fills all the world!

XVII.1-3

As Virgil calls this out, he also signals to the beast - who, at the end of Canto XVI, had floated up to them as if swimming through the air - to “come ashore.”

The edge of the cliff on which they stood - the great barrier which leads down to the Eighth Circle - was made of stone; upon this the beast rested his head and the trunk of his body, the rest of him hanging over the edge.

This beast is Geryon, a blend of three kinds of being: human, animal and reptile. His face is gracious and looks just; but this “outer semblance” is but a covering of this “filthy effigy of fraud” (XVII.7-8), referring to the Eighth Circle of Fraud, to which they will descend.

Geryon’s trunk was that of a serpent, his hands were paws, and hair grew all the way up his arms; over his back and chest and down to his flanks; the “twining knots and circlets” were beautiful patterns in the serpent skin, more beautiful than the woven cloth and carpets of the Turks and Tartars, or that most perfect cloth of the myth of Arachne.

Dante describes the way in which Geryon rested on the edge of the abyss; as a boat drawn onto the shore, or as a beaver, who in medieval bestiaries was said to settle on the edge of the water with its tail submerged in order to catch fish; this beasts forked tail moved and twitched.

As they walked along the stony edge to reach the spot where the creature rested, Dante noticed some other souls upon the burning sand that he had not yet encountered.

Virgil sends Dante to inquire into this new group, and bids Dante to question them so that he can understand every last detail about this third ring of the Seventh Circle. While Dante does this, Virgil is going to speak to Geryon and ask for his help. Dante went on alone to discover who they were:

So I went on alone and even farther

along the seventh circle’s outer margin,

to where the melancholy people sat.

XVII.43-45

These sad souls sat in the burning sand, alternatively waving away the falling flames and brushing away the burning sands, as dogs trying to free themselves from biting insects. These are those who committed the sin of Usury, or money lending with interest.1

Dante looked closely, and while he did not recognize any of the souls by their appearance, he did notice the coats of arms or family symbols upon the purses that hung round their necks; “apparently the usurers are unrecognizable through facial characteristics because their total concern with their material goods has caused them to lose their individuality.”2 Dante is highlighting the decline of the nobility into money making and greed by the examples of the families that he uses.3

The first had a yellow and blue purse with the image of a lion (59-60). This was the Florentine Gianfigliazzi family. The next had a red purse with the image of a goose upon it (62-63), the Obriachi family of Florence. The last had a white pouch with a blue pregnant female pig upon it (64-65); this family was from Padua, the Scrovengi. This soul - usually identified as Reginaldo degli Scrovegni - asked Dante what he was doing there, letting him know that his “neighbor Vitaliona” would be joining him there in the time to come (68).

The Florentines regularly shout at the Paduan to send down “the sovereign knight / who will come bearing three goats on his pouch” (XVII.72-73), indicating the “supreme usurer” Giovanni Buiamonte of the Becci family, a Florentine moneylender who went from immense wealth to dying in poverty. After saying this, Scrovegni grimaced and licked his own nose, like an ox, a taunt to the Florentines.

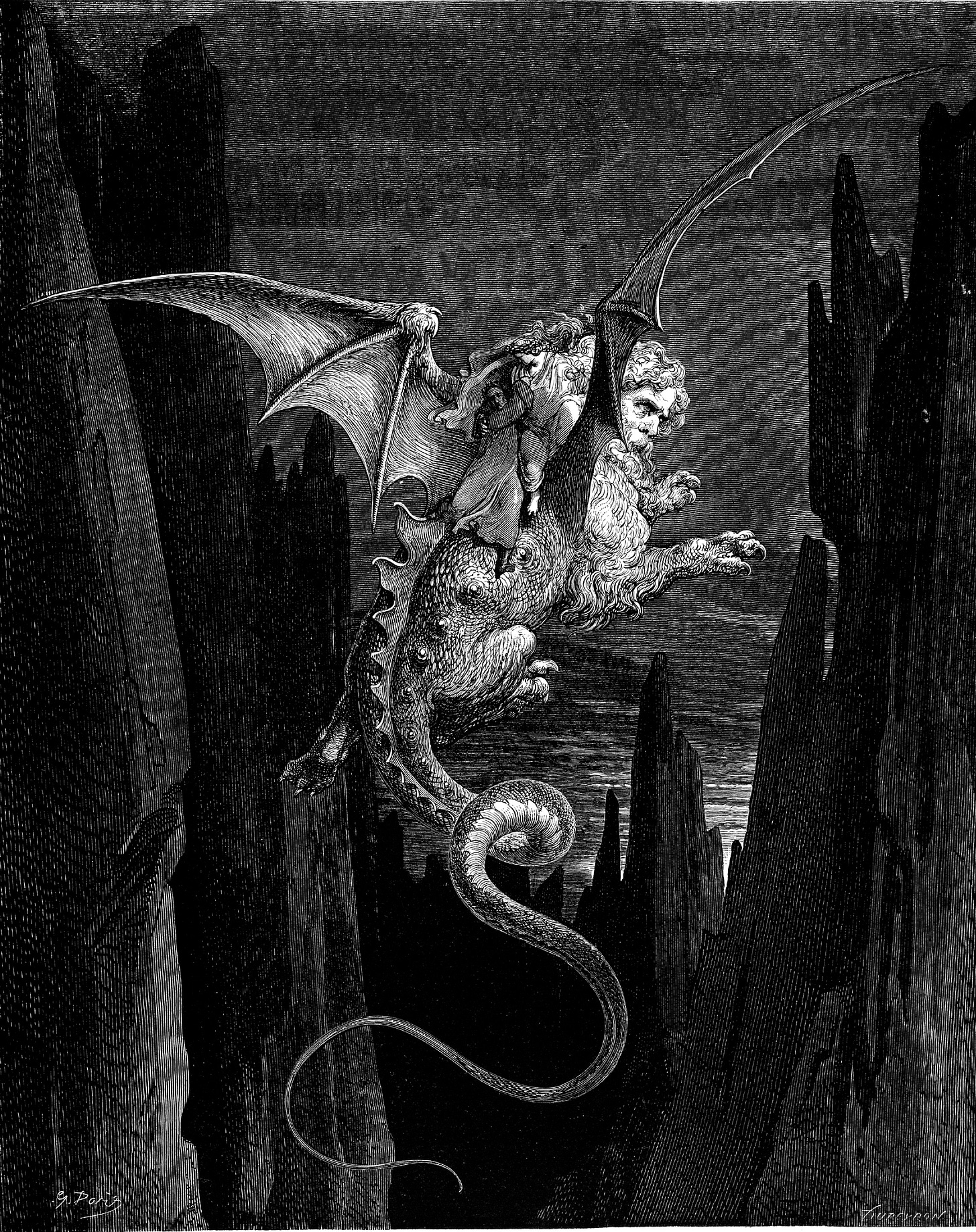

Dante had seen all that he needed to, and was eager to get back to Virgil. Virgil is prepared for him, and Dante learns how they are going to descend down the ledge into the Eighth Circle;

I found my guide, who had already climbed

upon the back of that brute animal,

and he told me: “Be strong and daring now,

for our descent is by this kind of stairs:

your mount in front; I want to be between,

so that the tail can’t do you any harm”

XVII.79-84

Virgil is protecting Dante from Geryon’s sharp tail, by having Dante sit in front of him upon Geryon’s back. The prospect of this endeavor, however, incites fear into Dante’s heart:

As one who feels the quartan fever near4

and shivers, with his nails already blue,

the sight of shade enough to make him shudder,

so I became when I had heard these words;

but then I felt the threat of shame, which makes

a servant - in his kind lord’s presence - brave.

XVII.85-90

So deep was his fear, that he desired to cry out to Virgil to hold him tightly, but his voice did not cooperate. Even so, Virgil knew what Dante needed; and as he had helped him out before,5 he did so now hold him tight as soon as Dante was firm upon Geryon’s back.

Now Virgil commands Geryon to fly in slow and gentle circles, to be mindful of the living weight upon his back.

He turned his tail to where his chest had been

and, having stretched it, moved it like an eel,

and with his paws he gathered in the air

XVII.103-105

To Dante’s medieval mind, the idea of flight belonged to birds of the air and myth, not to humankind. His impressions as they take off are of the tragic attempts of flight that failed; Phaethon, in his rash wish to drive the chariot of the sun without the strength or knowledge of how to do so, and his fiery end, “For which the sky, as one still sees, was scorched.” XVII.1086 - and Icarus, who flew too high to the sun, craving its brilliance and light, but went too far and whose waxen wings melted in the heat, he tumbled from heaven.

I do not think that there was greater fear….

than was in me when, on all sides, I saw

that I was in the air, and everything

had faded from my sight - except the beast.

XVII.106, 112-114

Dante is surrounded by the sensations of the depth that they are descending to; the cries and laments of the suffering souls and the flickering light as they travel down, down, and further down. It becomes more terrible the deeper they circle, closing in and growing tighter.

He compares that descent to that of a failed day of hunting for falcon and master, and the attitude of the bird, who:

Descends, exhausted, in a hundred circles,

where he had once been swift, and sets himself,

embittered and enraged, far from his master;

XVII.130-132

Geryon delivers them to the foot of the cliff, and shot off again as quickly as the boatman Phlegyas on the river Styx had approached them.7

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

The Devil pulls the strings which make us dance;

We find delight in the most loathsome things;

Some furtherance of Hell each new day brings,

And yet we feel no horror in that rank advance.

~ Charles Baudelaire

In Yeats’s poem ‘Second Coming’ there are mysterious verses that echo with a message of this canto:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

The final three lines resonate deeply: “The ceremony of innocence is drowned.” Dante’s journey so far can be divided into two distinct phases. The first, dominated by fear—paura being the most frequent word in the opening cantos. The second, marked by sympathy for the sinners, as he grapples with their suffering.

Yet, as he descends further, Dante’s understanding of sin hardens, and his judgment sharpens. The ceremony of innocence is drowned, and with it, his initial hesitations. What began in fear and compassion gradually transforms into a clearer vision of divine justice—one that demands recognition rather than mere pity.

Dante’s mind is still at risk; his journey is far from over. When Geryon rises from the abyss, his sharp, scorpion-like tail “did not draw onto the bank.” We see his three-part structure unfold: the face of a just man, a torso of deceptive beauty, and a hidden, barbed tail, poised to strike.

We have all been unfortunate at some point of our lives and have met Geryon in one form or the other. A creature who seduced us with a just face and beautiful appearance but whose tail was drawn to sting us when we become vulnerable and delirious by his appearance.

Geryon appears as the antithesis of Christ—where Christ is one in three, Geryon is three in one. If Geryon embodies the corruption of trust, Christ represents absolute truth and integrity.

In this canto Virgil (our reason) tests Dante’s firmness and allows him to speak to sinners alone, briefly, while he himself will “parley with this beast, to see if he can lend us his strong shoulders.”

I. Great Art Made by Great Sinners

Usury—profiting from money alone—was condemned as one of the gravest sins. Those who practiced it now sit hunched, their backs bent in perpetual toil, never rising from their ledgers. “With their hands kept fending off, at times the flames, at times the burning soil,” they are trapped in a ceaseless struggle, as if still counting their wealth, yet unable to escape the fires that consume them.

One such usurer, who would come to rule over Florence centuries later, was Lorenzo di Medici, one of the wealthiest bankers of his time. Lorenzo the Magnificent, well-versed in Dante’s work, feared that his soul might share the fate of those condemned in Inferno. In a desperate bid to secure his salvation, he followed the example of the son of a sinner Dante encounters—Reginaldo Scrovegni—seeking to atone for the weight of his wealth.

Yes, the same Reginaldo Scrovegni who ‘stuck his tongue out, like an ox that licks its nose.’

If Lorenzo became a patron for the great artists such as Leonardi, Michelangelo, Botticelli, Raphael and countless others - the son of Scrovegni aware of how his father made his wealth commissioned a Chapel - today known as Scrovegni chapel in Padua.

It' is one of the most beautiful places created during the early Renaissance, the chapel is decorated by Giotto.

Whether Lorenzo was consciously following Enrico Scrovegni’s path to salvation is difficult to determine, but what astounds me is that these wealthy bankers—usurers—feared for their souls in the afterlife. This fear was not merely a dogmatic terror of divine punishment; they understood why usury was condemned as a sin. It was sterile, unproductive—a wealth that begot nothing, a practice that bore no fruit.

Next time I stand in the Scrovegni Chapel or before Botticelli’s Venus and Mars, I will not only admire the artistry and genius but also recall that these works were born from a pursuit of salvation.

III. Reason Guards Our Back

Dante’s interaction with the usurers was brief and he returned to his guide to find that Virgil managed ‘to tame’ Geryon.

This might be speculation, but fraud deceives by denying us the chance for a second impression. While Dante was speaking with the usurers, Virgil—our reason—was perhaps observing Geryon, studying his tricks. The second time Dante sees Geryon, he appears less monstrous, and his pointed tail is no longer concealed behind the bank.

But no matter how long one studies the ways of fraud, it will always remain perilous. Fraud relies on speed hence later we will hear verses ‘he vanished like an arrow from a bow.’

This is why reason must remain ever vigilant. That is why Virgil sits behind Dante—Dante’s way of telling us that “reason should always guard our back.”

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

The Nature of ‘Paying Attention’: Geryon and Phaeton

Fraud relies not only on speed but also on seizing our attention and steering it toward its own wicked ends. The parallels between Dante’s descent on the back of Geryon and Phaëthon’s reckless chariot ride are striking. As mentioned before, Phaëthon failed because he lacked both strength and knowledge. In contrast, Dante is able to ride Geryon precisely because he has already gained sufficient strength—demonstrated by his ability to confront the usurers without Virgil’s aid—and the knowledge acquired from his encounters with previous sinners in the Inferno, allowing him to guide Geryon even deeper into Hell.

A lack of spiritual strength and knowledge strips us of the ability to direct our own attention.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

Just as a falcon long upon the wing—

who, seeing neither lure nor bird, compels

the falconer to cry, “Ah me, you fall!”—descends, exhausted, in a hundred circles,

where he had once been swift, and sets himself,

embittered and enraged, far from his master;such, at the bottom of the jagged rock,

was Geryon, when he had set us down.

And once our weight was lifted from his back,he vanished like an arrow from a bow.

Characters:

- Geryon - Creature of myth, he is sometimes depicted as three bodied or just three torsoed; in the fragments of the lyric poem Geryoneis he is described as winged, with three bodies and six hands and feet. He is “the monstrous son of the Oceanid Kallirhoe and Chrysaor (the son of Poseidon born from the Gorgon Medusa’s severed neck when Perseus cut off her head).”8 Virgil describes Geryon in passing in the Aeneid.9

Callirhoe, the daughter of Ocean, joined

in golden Aphrodite’s love with strong

Chrysaor, and she bore a son to him,

strongest of mortals, Geryones, he

whom mighty Heracles subdued and killed

to avenge his cattle with their shuffling feet,

on Erytheia, circled by the sea.

Hesiod Theogony 975-981

- Arachne - A skilled and proud weaver, she boasted that she could beat Athena - the goddess of craft (as well as of wisdom and warfare) - in a weaving contest. Athena came to Arachne in disguise to attempt to elicit an apology to the goddess for her boasting, but Arachne was unmoved and confident in her skill. Their contest began, and Arachne created a perfect work of the actions of the gods in tapestry; Athena was so outraged that she destroyed her work. Arachne hung herself in despair; only then did Athena take pity and transform her into the spider. Her story is told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses VI.1-208.

Then, as the goddess turned to go, she sprinkled

Arachne with the juice of Hecate’s herb,

and at the touch of that grim preparation,

she lost her hair, then lost her nose and ears;

her head got smaller and her body, too;

her slender fingers were now legs that dangled

close to her sides; now she was very small,

but what remained of her turned into belly,

from which she now continually spins

a thread, and as a spider, carries on

the art of weaving as she used to do.

Ovid, Metamorphoses VI.198-208

- Phaethon - The son of Phoebus (Apollo) and Clymene, he boasted of his parentage but was mocked by his friends as false, so he asked his mother for proof. She directed him to travel to his father to ask him himself, which he did. He was embraced by Phoebus, who as a boon to prove his honor, granted his son Phaethon any wish he may desire. Phaethon asked to drive his chariot of the sun and to guide his winged horses. Phoebus regrets his boon and tried to dissuade him. Phaethon sets out but cannot guide or control the fiery horses, and they wreak havoc on earth as the land is dried out, scorched, and burned, and Phaethon falls to his death like a comet falling from the sky. Phaethon’s story is told in vividly beautiful detail in Ovid’s Metamorphoses I.1038-II.453. Naiads receive his burnt body for burial:

Young Phaëthon lies here, poor lad, who dreamt

of mastering his father’s sky-borne carriage;

although he sadly died in the attempt,

great was his daring, which none may disparage”

Ovid Metamorphoses II.435-438

- Icarus - On the island of Crete, Daedalus and his son Icarus were imprisoned in the Labyrinth that Daedalus had built to contain the Minotaur due to King Minos’ rage that Theseus had killed the Minotaur and escaped with Ariadne. To escape, Daedalus crafted wings made of wax and feathers for himself and his son, warning Icarus to fly neither too low - where the sea spray would dampen the feathers - or too high - where the heat of the sun would melt the waxen wings. Icarus, in his zeal, flew higher and higher, and when the wax melted and his wings became damaged, he plunged into the sea and died.

The sun’s consuming rays, much nearer now,

soften the fragrant wax that bound his wings

until it melts. He agitates his arms,

but without wings, they cannot grip the air,

and with his father’s name on them, his lips

are taken under by the deep blue sea

that bears his name, even to the present.

And his unlucky father, now no more

a father, cries out, “Icarus, where are you,

where, in what region, shall I look for you?”

and then he saw the feathers on the waves

and cursed his arts.

Ovid Metamorphoses VIII.315-326

Exodus 22:25: If thou lend money to any of my people that is poor by thee, thou shalt not be to him as an usurer, neither shalt thou lay upon him usury.

Deuteronomy 23:19 Thou shalt not lend upon usury to thy brother; usury of money, usury of victuals, usury of any thing that is lent upon usury.

Musa 54n

Mandelbaum 583

Malaria

When shielding Dante from the gaze of the Gorgon in Inferno IX.58-60.

The Milky Way

A bowstring never shot an arrow off

That cut the thin air any faster than

A little boat I saw that very second

Inferno VIII.13-15

March, The Penguin Book of Classical Myth 201

Aeneid VII.662, VIII.202

As an aside...a lot of these families are still active. They are still bankers and you can see them in the social pages of outlets like the DailyMail, their children marrying each other in lavish ceremonies or the older ones emerging once in a while to go to charity balls. They use different surnames but they are still around.

Vashik - this is fascinating.

I love the quote from Yeats. I looked up it’s relationship to Chinua Achebe’s novel and found this analysis of the poem, but found it astonishing that the analysis made no mention of Dante, who surely was the inspiration for both the poem and the novel. But then, I would not have known either if I had not taken up Vashik’s challenge to read the Comedia. Developing knowledge is a lot like Dante’s journey, following our guides from one level to the next. https://interestingliterature.com/2024/12/things-fall-apart-centre-cannot-hold-meaning/