How to Fight the Devils That Stand in Our Way?

(Inferno, Canto XXI): Corrupt politicians and devils

Tell the truth and shame the devil.

~ Francois Rabelais

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Twenty-First Canto we enter the fifth pouch of the Eighth Circle and the Barrators. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Eighth Circle, Fifth Pouch - The Barrators deep in boiling pitch - Demons with pitchforks push the sinners under - Dante hides and Virgil speaks to Malacoda - The crowd of demons - They are allowed passage with the guidance of other devils - The sixth bridge is broken - They must find a way across.

Canto XXI: Summary

Dante and Virgil speak - as they begin to cross over the fifth bolgia - of topics undivulged; perhaps like the conversation among the poets in Limbo,1 we can only imagine how profound their discussion was. This Canto never specifically names the sin held here, but implies it; here are the Barrators, or those who sold public offices or favors, much in the same way as the Simonists did with the church.

The sinner condemned to punishment in this fifth bolgia of the eighth circle is guilty of corruption in public office (barratry), the very charge made against Dante when he was sentenced to exile.2

Dante looks down into the dark trench, going into an extended simile of the most important shipyard of his day, Venice. He gives us, in that sense, the imagery of the pitch used to repair ships during the slow winter season, and then brings that pitch into the darkness before them, worse for being “heated by God’s art, not fire” (XXI.15).

This boiling, bubbling pitch seemed empty, but as Virgil pulls Dante to the side, he sees exactly what it contains.

I turned around as one who is keen to see

a sight from which it would be wise to flee,

and then is horror-stricken suddenly—

who does not stop his flight and yet looks back.

And then—behind us there—I saw a black

demon as he came racing up the crags.

XXI.25-30

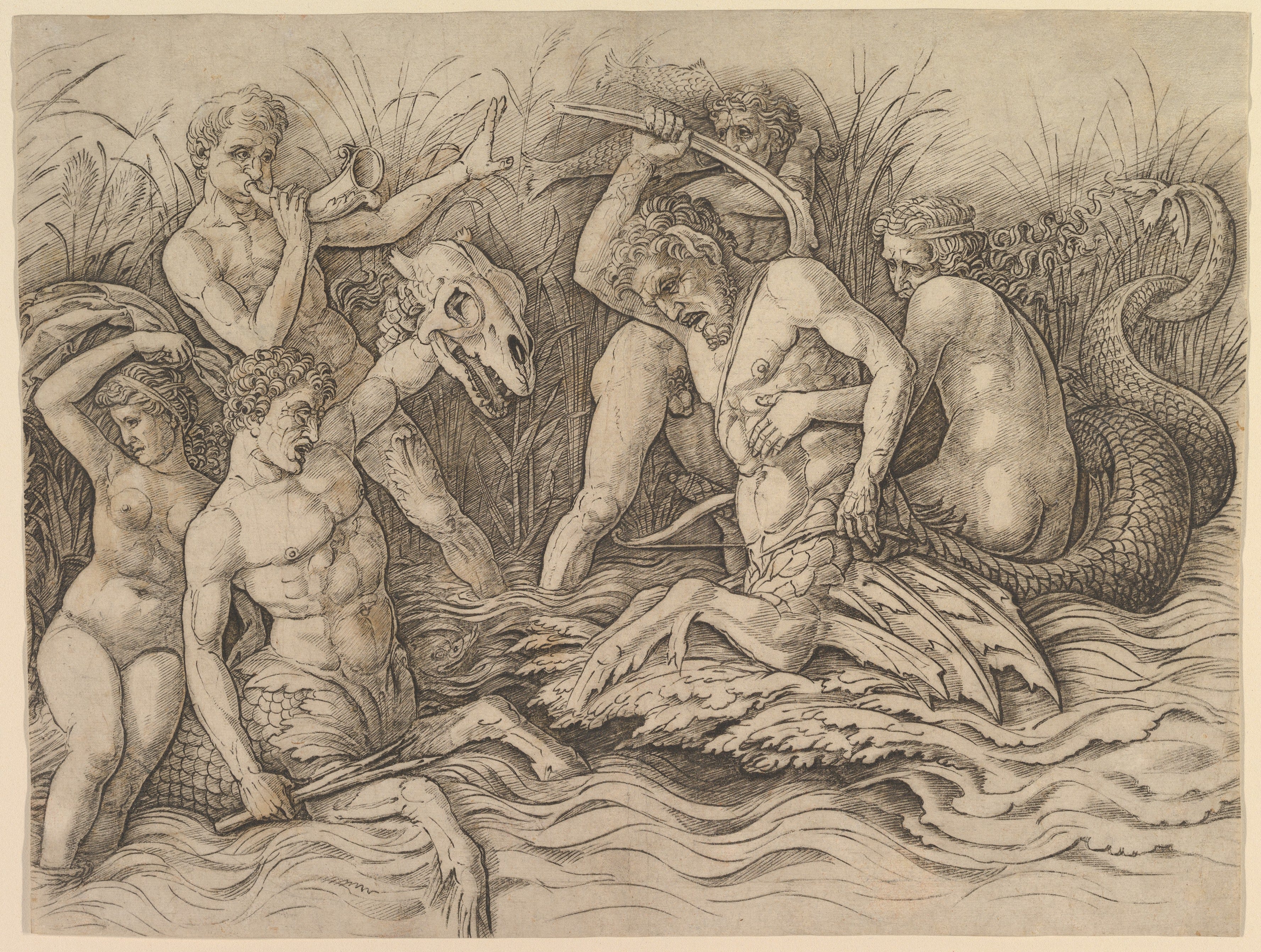

This demon ran nimbly along the rocks, his wings open, with a sinner slung over his shoulder as if he were carrying a carcass. The imagery of these demons are vivid, lively with personality, and characteristic of those found in medieval art. This running demon called out to the family of demons inhabiting this level - the Malebranche, or Evil Claws - that he had a sinner from Lucca ready to be thrown into the boiling pitch.

Then from our bridge, he called: “O Malebranche,

I’ve got an elder of Saint Zita for you!

Shove this one under—I’ll go back for more—

his city is well furnished with such stores;

there, everyone’s a grafter but Bonturo;

and there—for cash—they’ll change a no to yes.”

XXI.37-42

Saint Zita was the patron saint of the city of Lucca, west of Florence, which was well known for “grafters” and political corruption. The demon’s reference to Bonturo, the most corrupt member of that city, is sarcastic, as he was the worst of the lot. Changing a “no” to “yes” shows the ease with which political favors can be bought and sold.

As the sinner was thrown into the pitch, his position was like a figure on a crucifix, arms stretched out. It is this position that the demons mock, referring to the Sacred Face, Christ on the crucifix at Lucca whose imagery was also used on their coins. They mock that he cannot swim here as he does at home, in the Serchio River. Here, he will have to be pushed under and stay under, not swim for pleasure. They pushed him under with their prongs and pitchforks, mocking further by telling him he has to do his punishment in the dark and secret as he did in life.

Virgil has Dante hide so that he can talk to them, as he did before the gates of Dis.3 As Dante hid behind the rocks, Virgil boldly strode out after crossing the rest of the bridge, and the demons reacted like dogs, jumping out at him and blocking his way with their pitchforks.

Virgil rebukes them, asking one to step forward and hear what he has to say. They all call for Malacoda—“Evil Tail”—to step forward and speak, and Virgil tells Malacoda that his journey through these regions is willed from above:

“O Malacoda, do you think I’ve come,”

my master answered him, “already armed—

as you can see—against your obstacles,

without the will of God and helpful fate?

Let us move on; it is the will of Heaven

for me to show this wild way to another.”

XXII.79-84

Malacoda knew the significance of Virgil’s words, and all his rough pride was spent, he let the others know not to touch him. Virgil called Dante out of hiding, letting him know that all was now safe, and Dante sped to his side.

Dante’s comic terror in this bolge is, characteristically, a double-edged gibe at himself and his accusers.4

There is a feeling of two opposing sides not quite trusting each other; Dante was safe by Virgil’s side, but the demons were jesting as if they were going to treat him like the other sinners. Malacoda ordered them to be still, pointing out one by name, Scarmiglione.

To us he said: “There is no use in going

much farther on this ridge, because the sixth

bridge—at the bottom there—is smashed to bits.

Yet if you two still want to go ahead,

move up and walk along this rocky edge;

nearby, another ridge will form a path.

XXII 106-111

The section of bridge across the sixth bolgia has been shattered, so the pilgrim and the poet must find another way across. Since the shape of the Eighth Circle with its ten trenches is like a wheel with spokes—bridges—leading into the center, the demons are saying there should be more than one archway across to the 6th bolgia.5

Malacoda offers the guidance of a group of his demons to guide them down the ring to what he says is one of the last unbroken spots to cross over. As the demons guide them, they can also “see if any sinner lifts his head for air,” (XXI.116) thereby checking on the state of the rest of the sinners submerged in the boiling pitch. He names the moment of the bridges being “smashed to bits,”6 relating to other broken sections that they are familiar with, in timing the exact moment that Christ’s presence shook the underworld.

Malacoda calls out the ten demons who will accompany Dante and Virgil: Alichino, Calcabrina, Cagnazzo, Barbariccia (who gets to be the captain of the group), Libicocco, Draghignazzo, Ciriatto, Graffiacane, Farfarello and Rubicante.

Dante has his doubts about using such guides, and prays to Virgil to leave the demons behind—whose winks and grinding teeth seem suspicious to him—and let the two of them find the bridge themselves. Virgil reassures Dante, saying that their expressions are for the benefit of the sinners, not of themselves.

They depart, the band of ten making juvenile noises with their mouths, as their captain Barbariccia trumpets his flatulence as a signal to be off.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

“Названный дьявол не так страшен.”

(Nazvannyy dyavol ne tak strashen.)

“The named devil is not so frightening.”

~ a Russian proverb

It is fascinating to think that the corrupt politicians are punished in Inferno by equally corrupt devils. Just as the Centaurs in the Seventh Circle—half-beast, half-man—reflected the bestial nature of the violent they guarded, so too do the devils of this bolgia reflect the cunning, malicious traits of those they torment. In Dante’s vision, the corrupt politicians among us resemble devils, and some of us, if not all, must have seen them first hand in the real life.

I. The named devil is not so frightening.

When the frenzied crowd of devils rushes toward Virgil, “with the same frenzy, with the brouhaha of dogs,” our wise guide calmly asks that just one of them should step forward. Virgil, our reason, ever composed in the face of chaos, knows this truth: to confront a devil, one must first know its name.

Once again a Russian proverb comes to my mind here: The named devil is not so frightening. This wise saying reminds us that it is impossible to deal with a crowd of frenzied deceitful unidentified devils, but you can tackle them one by one if you know them by their name. And, in this bolgia, we learn many names of corruption.

The first one who steps forward is Malacoda, or Evil-Tail (mala - bad, evil, coda - tail). It is impossible not to recall Geryon, who concealed his venomous tail—the very instrument of his treachery—beneath the bank when we first encountered him.

The next devil that awaits behind the Evil-Tail is Scarmiglione, he seems to be impatient since Malacoda turns to him and says: ‘Be still, Scarmiglione, still!’ Scarmiglione comes from the word ‘scarmigliare’ or ‘to mess up’.

“…go with my men—there is no malice in them.”

~ Malacoda

The Evil-Tail speaks with such assuredness, as if he has forgotten that he is, in fact, a devil. It is a striking psychological insight Dante offers us: the most insidious trait of evil is its ignorance of itself—or worse, its denial.

Malacoda says ‘go with my men - there is no malice in them’ and sends with our two companions ten troops - Alichino (Harlequin, trickster, false servant); Calcabrina (calcare - ‘to step on’); Cagnazzo (cagna ‘female dog’ with added -azzo, he raises suspicion, distrust, false narratives); barbariccia (derives from barba—beard—which itself symbolises wisdom. Riccia translates as curly, and thus barbariccia suggests a kind of “curled wisdom”: not the clear, upright wisdom of a philosopher, but one that is twisted, coiled, obscured.)

We can continue on with Draghignazzo (or Sneering Dragon, connected to corruption of greed, bribes); Graffiacane (Scratch Dog punishes the damned with the same brutal, mocking violence they once inflicted in life—a grotesque mirror held up to their former selves, where cruelty answers cruelty with hellish symmetry).

I, as perhaps many of you, was terrified when the crowd of devils rushed toward Virgil. Gustave Doré’s vision of this scene heightens that terror—but I must admit, once the devils are named and we begin to understand what they stand for, the fear begins to subside. It’s as if reason, by shedding light on chaos, makes it bearable. Once we know who they are, we can face them.

II. Reason and Soul

Virgil leaves Dante for the third time in this scene. The first time was when we stood outside the city of Dis; then when he tamed Geryon; and now here. It is, as if Dante tells us that certain evils must first be met with reason and only then by our soul.

It is also fascinating that it is Virgil—Reason—who declares to the devils that this journey is divinely ordained. One might expect that, despite Virgil being our guide, it would be the soul itself that must call upon divine aid.

Why is it Virgil who declares the divine path, and not the soul itself?

There can be no eudaimonia - or a good life - without reason. But, when we stand against the crowd of devils, it is equally reasonable to think that you cannot fight them as to think that you can. It would be perfectly reasonable for Virgil to say that there are plenty of devils, much more than any soul can handle, so it is reasonable for us to remain where we are. And yet a reason that is divinely inspired, or better to say in a secularised way, a reason who believes that it can overcome any devil on its way, will reach a virtuous life.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

What does Dante hide in this canto?

We came along from one bridge to another,

talking of things my Comedy is not

concerned to sing. We held fast to the summit,(lines 1-3)

There were many interpretations of these lines by almost every commentator I have read so far. I wonder what Virgil and Dante discuss and what exactly ‘my Comedy is not concerned to sing.’ We have encountered this case before, when we were in Limbo and met the virtuous pagans. Dante walked with the great poets but remarked in his poem that his poem will not reveal what they discussed.

Crowd of Devils

Devils never walk alone. They prey on our scattered attention, descending upon us in crowds. It was only when Virgil demanded to speak with one alone that the blurred mass became distinct, and their faces, once chaotic, took on form.

Look at Gustave Doré’s illustration at the top of Philosophical Exercises—the devils attack our companions in numbers. Their strength is not just in force, but in confusion. When Malacoda offers (false) directions, he sends a crowd to accompany Dante and Virgil. Deception, in Dante’s vision, rarely walks alone—it hides in the chaos of many.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

Let us move on; it is the will of Heaven

for me to show this wild way to another.(83-84)

Inferno IV.103-105

Singleton 368

Inferno VIII.106-108.

Sayers Hell 206

Without spoiling future events, are the words of these demons to be trusted?

Inferno V.34, XII 31-45

Hi, Vashik and Lisa: I don’t know if anyone else is having difficulty with this, but I am finding it increasingly hard to participate comfortably because the chats are starting to lag significantly behind the move to new cantos. Part of the enjoyment of this for me is to be engaged with each canto all of a piece through your superb essays and then by sharing observations in chat discussion on the given canto assignment while it is “live.” If you are finding that your own time constraints make it difficult to keep up with preparing each canto’s essay and prompts for the chat “in sync,” one possibility could be to open the chat without a specific set of prompts at the same time as you put up the essay for each canto. Now, perhaps I am an outlier with this concern, and if so, of course go with the sense of the group.

Having ventured through Christian subconscious myself too, you can expect this sort of hell of passions. But it’s quite natural, it is calling it sinning that anatagonizes their vital role in existence - the energy. That created all sorts of blasphemous conceptions of life even portraying reproduction and enjoyment as sins that affected mass psychology so deeply that it actually created Hell that doesn’t exist for not aware of it minds. Superstitions we call it, but it’s very real when it roots in subconscious mind working on other, more grim frequencies stimulating muscles and strength. Of course a beast is dangerous when hunting but it doesn’t hunt its family. It’s feeding them, which actually starts to lead towards conception of morality even in lower animals (at this point). It starts as instinct, then becomes habit and ends with desire asking where is it after it disappears. Then comes desperation, withdrawal. Either finding new source or changing themselves to fit new circumstances. Down numberless generations, this becomes fundamental of specie on which it builds and also niches out mingling with different plateaus around the feeding grounds.