Love & Strife: Are We Masters of the Beast Within?

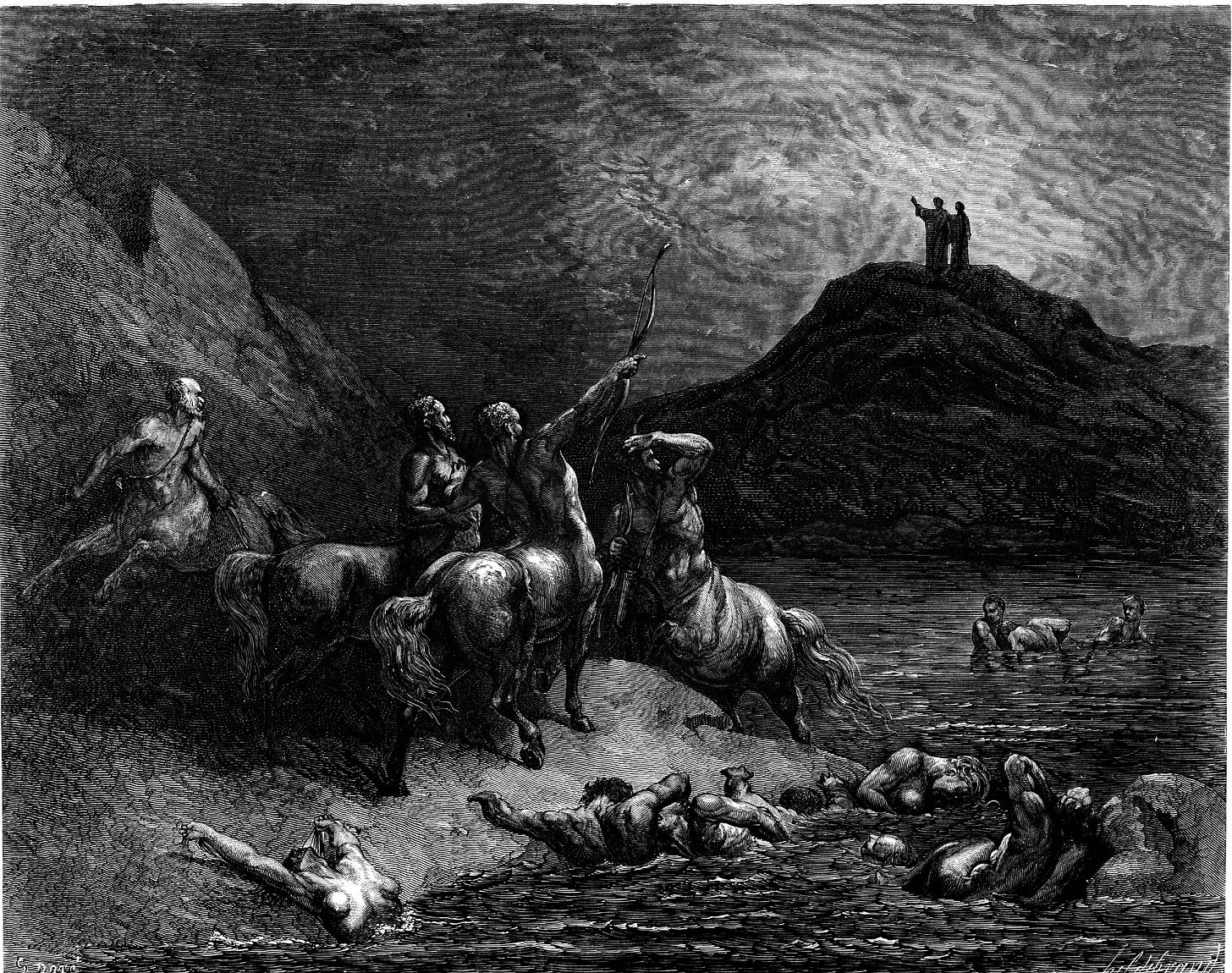

(Inferno, Canto XII): Minotaur, Alexander the Great, Centaurs and violence

Another thing I will tell you: there is no birth for any

mortal thing, nor any cursed end in death;

only mixing and interchange

of what is mixed, those things are – but man named them birth.

~ Empedocles (quoted by Plutarch in Against Colotes)

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

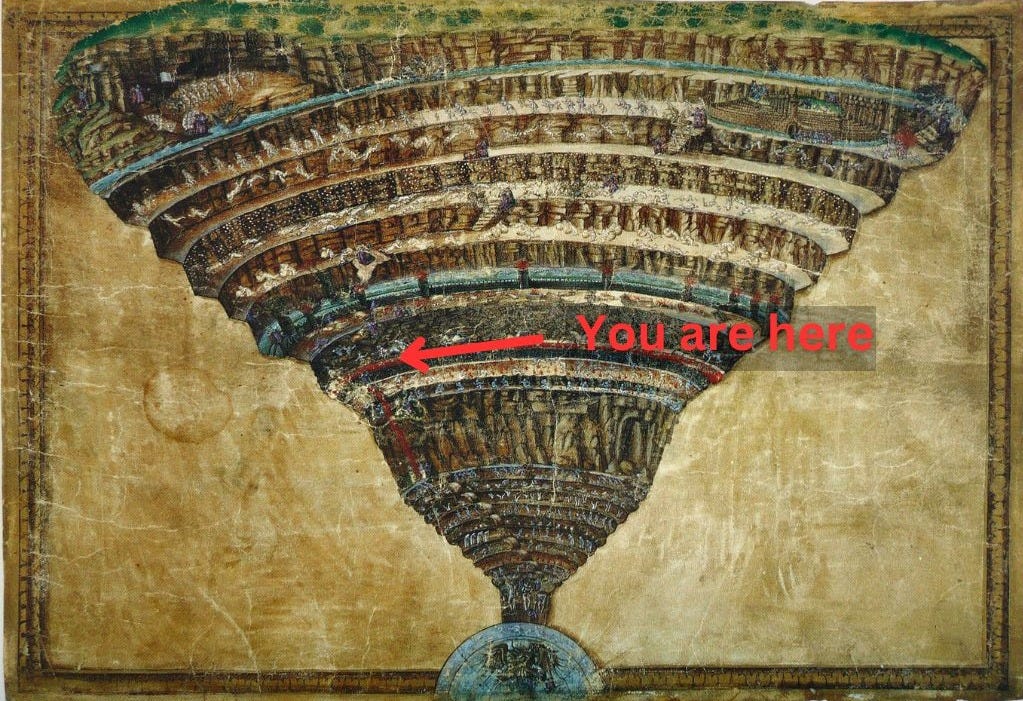

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Twelfth Canto we find the Centaurs and the River Phlegethon. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Dante and Virgil descend into the Seventh Circle - The first ring of the Violent against others - The Minotaur guardian - The river of blood, the Phlegethon - The Centaurs - Sinners submerged in the boiling blood - Dante and Virgil ford the river.

Canto XII: Summary

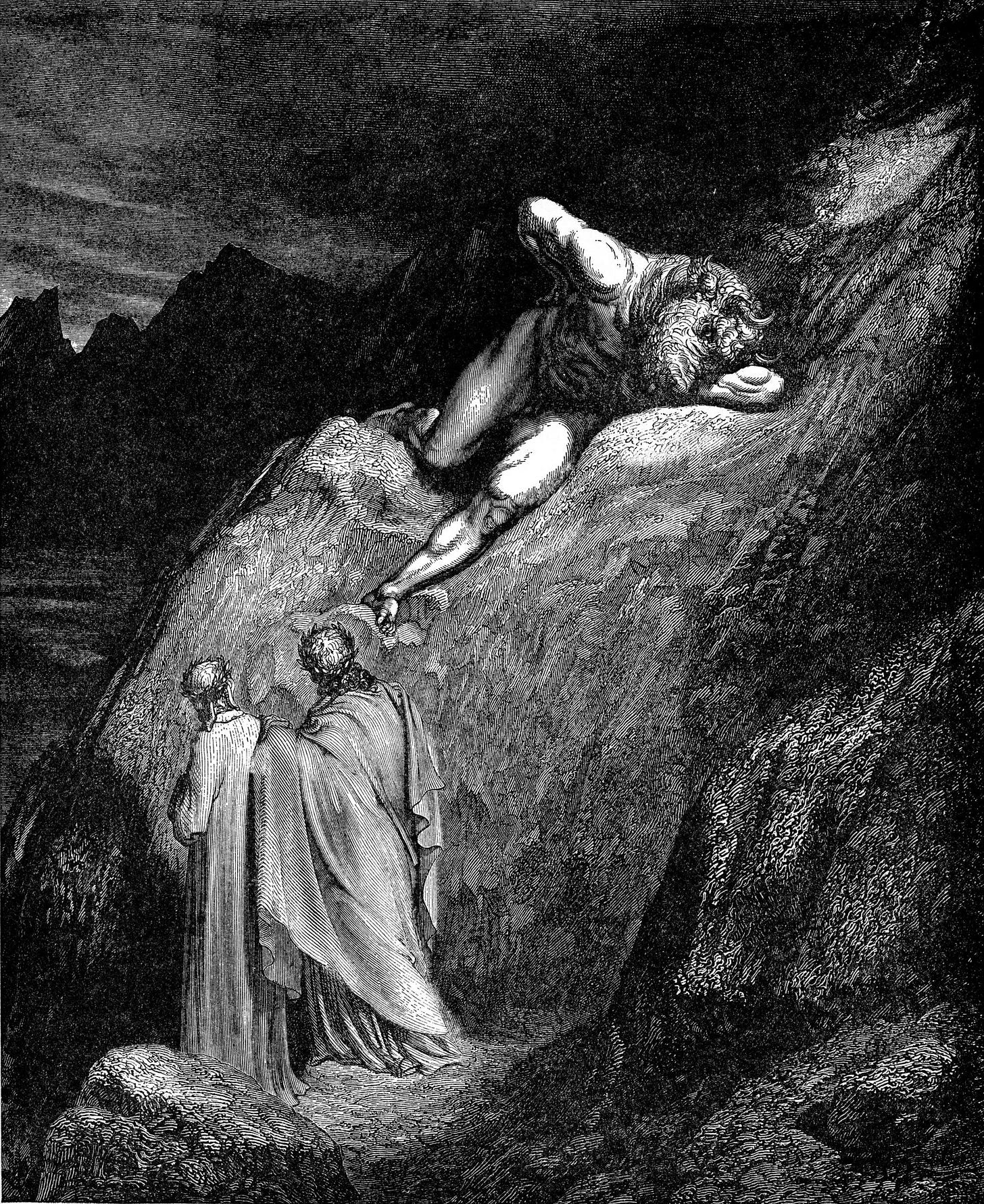

Dante describes the descent from the rim of the Seventh Circle down into the first ring, those who were violent toward their neighbors and property; it was a steep, rocky descent, reminiscent of banks of the Adige, a river in Italy, and “what reclined upon that bank” brings a sense of terror in it’s anonymity.

That which reclined upon the bank was the Minotaur, the “infamy of Crete” (XII.12). A man with the head of a bull, the Minotaur is a creature given over to its animal nature; it’s existence in fury so complete that it even bites itself in its expression of “self consuming rage”1 in that same self mutilating expression we saw with Filippo Argenti.2

Virgil addresses the Minotaur, saying that it is mistaking Dante for the Greek hero, Theseus3 who slew it in the labyrinth. Ariadne was the fully human sister of the Minotaur, daughter of the King of Crete, of the famed Ariadne’s thread. To help Theseus find his way through the labyrinth, she gifted him with a ball of thread that he could unwind as he went, in order to find his way back out.

Just as the bull that breaks loose from its halter

the moment it receives the fatal stroke,

and cannot run but plunges back and forth,

so did I see the Minotaur respond

XII.22-25

His blind rage gives them the chance to slip by him, as he is so overtaken with the violence of his fury.

They climbed down the bank, the rocks tumbling under the weight of Dante’s feet. Virgil, seeing Dante deep in thought, asks if he is thinking about the mass of rock they are climbing down. He references the last time that he traveled in this spot4 there had been no collapse of stones; they collapsed when all of Hell was shaken in the earthquake at Christ’s crucifixion,5 before the Harrowing of Hell6 when he descended to rescue the patriarchs from Limbo. Notice that Christ is always referred to in roundabout ways; his name is never said in Hell.

On all sides, the steep and filthy valley

had trembled so, I thought the universe

felt love (by which, as some believe, the world

has often been converted into chaos);

and at that moment, here as well as elsewhere,

these ancient boulders toppled, in this way

XII.40-45

That love that Virgil is referencing is the love from the sacrifice of Christ, reaching even into those depths. But who is he referring to when is says “as some believe?” Look to the philosopher Empedocles,7 whose “theory of the alternate supremacy of hate and love as the cause of periodic destruction and construction in the scheme of the universe.”8

Empedocles taught that the universe was held together in tension by discord among the elements; but that from time to time the motions of the heavens brought about a state of harmony (love). When this happened, like matter flew to like, and the universe was once more resolved into its original elements and so reduced to chaos9

From their vantage, Virgil asks Dante to look down for his first sight of Phlegethon, the river of boiling blood, filled with “those who injure others violently” (XII.48). Dante laments such an affliction as this:

Oh blind cupidity and insane anger,

which goad us on so much in our short life,

then steep us in such grief eternally!

XII.49-51

Cupidity and rage are the two passions which, more than others, prompt deeds of violence against one’s neighbor and against his property-rage being responsible for the former, cupidity for the latter.10

Around the edge of this river were Centaurs, armed with arrows, gathered threateningly together upon seeing Dante and Virgil descend. Like the Minotaur, the Centaurs, known for gluttony and violence, are symbolic of the bestial nature that can overtake humanity; they represent “perverted appetite - the human reason subdued to animal passion.”11

Three Centaurs came forward - Nessus, Chiron and Pholus. Perhaps these three “typify three passions which may lead to violence: wrath, lust, and the will to dominate;”12 Nessus demands explanation from them, but Virgil will only speak with Chiron, knowing him to be the wisest of the three.

There are thousands of Centaurs circling the river of blood, shooting arrows at any sufferers who lifted themselves out of the thick, boiling river “more than its guilt allots” (XII.75). Chiron came forward and Virgil explains that their position is blessed by Beatrice; they are not there to thieve one away from Hell, as did Orpheus or Theseus. In fact, “necessity has brought him here, not pleasure” (XII.87); referring to Dante’s journey not of curiosity, but salvation. Virgil asks for a guide to help himself and Dante find their way over the river, and Chiron appoints Nessus.

As they walked, they could see that the gravest sinners were in the boiling blood up to their brows; “these are the tyrants / who plunged their hands in blood and plundering” (XII.104-105). Dante names Alexander and Dionysius, Ezzelino, and Obizzo of Este.

Next, were those in blood up to their throats, the murderers, including one who “within god’s bosom, he impaled / the heart that still drips blood upon the Thames” (XII.118-19). In the 13th century, inside the protective mantle of the church, Guy de Montfort assassinated the cousin of Edward I of England - Prince Henry - in revenge for his own father’s death, who was killed by Edward I. Prince Henry’s heart is the one that drips for his unavenged murder; “his heart was placed in a golden cup above a column at the head of London Bridge where it still drips blood above the Thames.”13

The sinners are rising, shallower in the river as their crimes lessen; the next group has their chests clear of the river; these would be those who committed violence against property rather than people. Dante recognizes but does not identify some of these souls. They are able to cross, and Nessus explains that within the circular route of the river that now they have reached the shallowest part, it will continue to deepen back into the level of the tyrants. More are named, including Attila, Pyrrhus, Sextus, and Rinier of Corneto and Rinier of Pazzo. Nessus leaves them.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

But insofar as they never cease their continual change, to that extent they exist forever, unmoving in a circle.

~ Empedocles

I. Minotaur

Just as the bull that breaks loose from its halter

the moment it receives the fatal stroke,

and cannot run but plunges back and forth,so did I see the Minotaur respond;

and my alert guide cried: “Run toward the pass;

it’s better to descend while he’s berserk.”

Most modern commentators, but not all, believe that Dante, in a reversal of the classical tradition, gave the Minotaur a man's head upon a bull’s body.14 Mikhail Lozinski, one the most esteemed Dante scholars, observes the same in the great Florentine’s portrayal of the mythical beast’s behaviour.

So, which is it? A body trapped in a bull’s form, or merely a head imprisoned in a bull’s body?

We have entered Lower Hell, where the sinners of intellect—the willfully damned—reside. One might expect the classical depiction of the Minotaur to prevail here: a bull’s head upon a human body, symbolising a mind ensnared in the labyrinth of bestial violence.

But what if, as some modern commentators suggest, Dante envisioned the mind trapped within a bestial body?

This would symbolise the body overpowering the mind. To understand this better, we must look at the next mythical creatures Dante and Virgil encounter—after the Minotaur, lost in his own bestial madness, allows them to pass…

II. Wise Violence: Life for Life, Eye for Eye

I saw a broad ditch bent into an arc

so that it could embrace all of that plain,

precisely as my guide had said before;between it and the base of the embankment

raced files of Centaurs who were armed with arrows,

as, in the world above, they used to hunt.On seeing us descend, they all reined in;

and, after they had chosen bows and shafts,

three of their number moved out from their ranks;

The Centaur is another creature, part beast, part human. For Dante, influenced by Aristotle and Aquinas, intellect is what sets humans apart in nature. To commit violence—senseless, unreasoned violence—is to betray the greatest gift bestowed upon us by God: the intellect.

What fascinates me is that the first Centaur to speak to our companions is Nessus, yet Virgil—our reason—chooses to address Chiron, the wisest among them.

Chiron, the mentor of Achilles, Aesculapius, Hercules, and other Greek heroes, embodies the highest form of wisdom within centaurs. In this, Dante conveys a profoundly beautiful message.

Who were Achilles or Hercules? They were warriors, heroes, they were famed by their strength and ability to trample over the monsters of superior strength. What would a mentor like Chiron teach them? To control their strength, to wage violence by wise guidance, to never let the violence of your body control to control your mind.

You might say why then does Chiron assign Nessus to carry Dante across the river full of blood?

Having sought counsel from Chiron and received the wisdom needed, Virgil leads Dante forward. But this journey—ours as well as his—is not one of mere curiosity; it is a path toward salvation. We must learn to tame the violence that dwells within us.

Then I turned to the poet, and he said:

“Now let him be your first guide, me your second.”A little farther on, the Centaur stopped

above a group that seemed to rise above

the boiling blood as far up as their throats.He pointed out one shade, alone, apart,

and said: “Within God’s bosom, he impaled

the heart that still drips blood upon the Thames.”

Virgil momentarily relinquishes his role as guide, entrusting it to the Centaur, who will explain, one by one, why each sinner they encounter belongs in this place.

Coming back to the previous point I would like to draw your attention that Centaur, in contrast to Minotaur, is traditionally described as half-human half-horse. His head, his mind, is that of a human and the body of that of a horse.

I humbly refuse to engage into a debate with the leading scholars on Dante, yet in my modest opinion, Dante adheres to the classical depiction of the Minotaur. The Centaurs, to varying degrees, have tamed their bestial nature. Their human heads signify reason prevailing over instinct. One does not need to have hooves to recognise that, like the Centaurs, we too must master the beast within.

The Minotaur, however, is their inverse—a mind conquered by its own brutish form. Thus, I find the traditional interpretation of the labyrinth-bound beast more fitting.

But what is this duality, this tension—between love and hate, between Christ and the Earthquake, between the beast and the mind?

III. Empedocles

For Empedocles, the pre-Socratic philosopher, the world was composed of four elements—earth, air, fire, and water—governed by two opposing forces: Love and Strife. Strife disassembles the old order, allowing a new combination to emerge.

Dante, with his characteristic genius, presents the river Phlegethon as a perversion of Empedocles’ cosmic order. Hell’s fire does not purify but makes blood boil—blood itself a corruption of water. The stench that permeates Hell is the corruption of air, while the bodies of sinners, trapped in torment, stand as a twisted reflection of earth.

As Dante and Virgil descend into this circle, they encounter shattered rocks—fragments broken apart at the moment of Christ’s crucifixion.

In Empedocles’ cosmology, certain events shake the existing order, forcing all things to reassemble. True, natural Strife dismantles elements that no longer belong together, so that Love may reunite those that do.

Violence is a corrupted form of Strife. It does not break apart to restore harmony but instead distorts the natural order—just as the tyrants submerged in Phlegethon once did. It forces together what does not belong.

This is why the Minotaur and the Centaurs appear so unnatural, their bodies an uneasy fusion of halves that do not match. Violence does not merely destroy harmony—it forges monstrous unions of mismatched elements.

I cannot conclude this section without asking—isn’t Dante a genius?

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Themes 🖼️ :

The word ‘Anger’ (Ira)

The word anger is mentioned more times than in any other canto in The Divine Comedy.

Centaurs’ Arrows

The Centaurs punish the damned who dare to rise from the river with bows and arrows—violence wielded against the violent. As an extension of our second philosophical exercise, it is worth noting that they embody a form of divine, wise violence used to restrain the bestial.

Why do the violent raise their heads above the river of blood?

Of course, they seek to escape punishment—but one might also speculate that tyrants and the violent always deny the extent of their own bestiality. They lift their heads in willful defiance (and it is worth recalling that, from this point on, all sinners are damned by choice), refusing to acknowledge the full measure of their brutality.

Hesiod’s Works and Days

I thought the work by Hesiod matches the wisdom of Empedocles in this. I copied these verses to my notebook four months ago, he describes the importance of Strife, and the different natures of it.

Strife is no only child.

Upon the earth, two Strifes exist: one is praised by those

who come to know her, and the other is blamed.

Their natures differ: for the cruel one

makes battles thrive and war; she wins no love,

but men are forced, by the immortals’ will,

to pay the grievous goddess due respect.

The other, first-born child of blackest Night,

was set by Zeus, who dwells in the air on high,

deep in the roots of the earth, an aid to men.

She urges even the lazy to work:

A man grows eager, seeing another grow rich

from ploughing, planting, and ordering his house.

So neighbor vies with neighbor in the rush for wealth—

this Strife is good for mortal men.

Potter hates potter, carpenters compete,

and beggar strives with beggar, bard with bard.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

but if I reason rightly, it was just

before the coming of the One who took

from Dis the highest circle’s splendid spoilsthat, on all sides, the steep and filthy valley

had trembled so, I thought the universe

felt love (by which, as some believe, the worldhas often been converted into chaos);

and at that moment, here as well as elsewhere,

these ancient boulders toppled, in this way.

Characters:

- Minotaur - Offspring of Pasiphaë, the Queen of Crete, who was cursed by Poseidon to desire a bull that he had sent for sacrifice as a sign to Minos, King of Crete (whom we saw in Canto V), when Minos did not sacrifice it as promised. Daedalus helped Pasiphaë by creating an “effigy” of a cow that she could hide in to receive the bull. The offspring was the Minotaur, who was banished to live in the labyrinth of Daedalus. There he devoured the tribute of the youth from Athens as revenge of Minos due to the death of his son Androgeos. When Theseus slew the Minotaur, he ended the custom of tribute.

- Phlegethon - The third Underworld river encountered in the Inferno after Acheron and Styx, Dante’s Phlegethon circumnavigates Circle Seven’s first ring of the Violent against Neighbors. In Virgil’s Aeneid, the Phlegethon run around the fortress of Tartarus:

Aeneas sees an extensive fortress, encircled by triple defence walls.

Round them Phlegethon roars. Grim Tartarus’ river of lava

Blazes with white-hot flame, spits rocks out hissing and clashing.

Aeneid VI.548-551

Macrobius, in his commentary on Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis, examines the rivers of the Underworld as representative of disorder in the human being. “Everything that fable taught us to believe was in the lower regions they tried to assign to us ourselves and to our mortal bodies…they thought that Phlegethon was merely the fires of our wraths and passions”

(128 I.x.11)

- Nessus - Centaur best known for the myth in which he is killed by Hercules upon at attempted assault on his wife, Deianira. He exacted vengeance by giving her a potion made with his blood - which was poisonous - as he was dying. Deianira, thinking it a love potion, used it on Hercules, and which brought about his death.

- Deianira - Daughter of Oineus, she was betrothed to Hercules, and upon traveling after their marriage, set to cross the River Evenos of whom Nessus was ferryman. In carrying Deianira across the river, Nessus attempted to rape her, upon which Hercules shot him with an arrow. Nessus’ dying action was to give Deianira what he called a “love potion” to use on Hercules.

At a later juncture Deianira was fearful of losing the love of Hercules, and so used the “potion” from Nessus on a tunic and gifted it to Hercules. The poison burned away his flesh and caused such pain that Hercules built his own funeral pyre in order to die and bring himself out of his misery. He thus burned away his mortal self and obtained immortality. Deianira hanged herself when she learned the outcome of the love potion.

- Chiron - The wise Centaur tutor of Greek heroes, including Achilles, Asclepius, Peleus, and Theseus. His father, Saturn, changed form into a horse during an encounter with Philyra to hide his form from his wife; Chiron was the offspring, and abandoned by Philyra, Chiron was raised and taught by Apollo and Artemis.

- Pholus - Found in the fourth labor of Hercules with the Erymanthian boar. Hercules was a guest of Pholus, and convinced him to open the store of the Centaurs wine, against Pholus’ better judgment. They both were attacked by the Centaurs whose stolen wine it was. Hercules fought them successfully, and the Centaurs fled to Chiron for refuge. Pholus, in picking up one of Hercules’ arrows, amazed that such a small thing could kill a human, dropped it onto his foot, and died from the poison that Hercules had tipped it with.

- Alexander - Scholars have debated if Dante was referring to Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) or Alexander the Tyrant (ruled circa 369 - 356 BC) of Pherae in Thessaly, who was widely known for his cruelty. Singleton goes into depth on the discussion of the two Alexanders and proofs for each.15

- Dionysius - Tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily (405-367 BC). His son, Dionysius the Younger was also a tyrannical ruler after him.

Macrobius tells a famous story of Dionysius the Tyrant: “Take the case of Dionysius, that ruthless tyrant of Syracuse. Wishing to show a former servant of his, who thought that the tyrant’s life was the only truly blessed one, how really wretched it was and how constantly he was in fear of threatening danger, he arranged a banquet and had a sword unsheathed and let down by a slender horsehair attached to the hilt, with the point poised over the flatterer’s head. Costly viands lay before him and all the splendor of the Sicilian court, but when in the face of death he begged to be released, Dionysius said, “Such is the life that you suppose is blessed. This is the sort of death we always see before us. Consider when a man can be happy who never ceases to fear”16

- Ezzelino - Ezzelino III da Romano, the “Ghibelline lord of the March of Treviso,” he was known as the “son of Satan” due to the atrocities he practiced. Villani, the thirteenth century Florentine historian, has this to say about him in his Nuova Cronica: “He caused many others to die by various tortures and torments and at one time had eleven thousand Paduans burned.”

- Obizzo of Este - Obizzo II d’Este, a Florentine Guelf, was the cruel Lord of Ferrara and reportedly murdered by his own son.

- Attila - Attila, king of the Huns (433-453) was called the “scourge of God.” He brutally sacked and plundered parts of the Roman Empire and Gaul.

- Pyrrhus - Son of Achilles, he violently killed Priam, King of Troy, along with members of his family, during the Trojan War. Virgil says he was “true heir to his father’s violence.” Aeneid II.491

- Sextus Pompeius Magnus Son of Pompey in the era of Julius Caesar and a notorious pirate, we saw Sextus visiting the witch Erichtho in Inferno IX.

- Rinier of Corneto and Rinier of Pazzo: Highway robbers in Dante’s time.

I used some of Francisco Goya’s masterpieces. More on Francisco Goya’s terrifying paintings and life:

Singleton, Commentary on Inferno 186

Inferno VIII.62-63

Dante simply refers to Theseus as The Duke of Athens; many times we see the familiarity with certain figures precludes needing to use their names; The Poet is Virgil, the Philosopher is Aristotle, etc.

Inferno IX.22-24

Matthew 27:51: And, behold, the veil of the temple was rent in twain from the top to the bottom; and the earth did quake, and the rocks rent.

Inferno IV.52-61

“If strife had not been present in things, all things would have been one, according to him; for when they have come together, ‘then strife stood outermost’” Aristotle Metaphysics III.4.1000b

Singleton 189

Sayers Hell 147

Singleton 190

Sayers Hell 146

Sayers Hell 147

Musa Inferno XII.120n

Hollander, Inferno, 228

Singleton 196-197

Macrobius, Commentary on Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis I.x.17. The story is often referred to as the Sword of Damocles.