If You Pursue Your Star, You Cannot Fail to Reach a Splendid Harbour.

(Inferno, Canto XV): Violent against Nature, Brunetto Latini

Far best is he who knows all things himself; Good, he that hearkens when men counsel right; But he who neither knows, nor lays to heart another's wisdom, is a useless wight.

~ Aristotle, Nichomachean Ethics

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

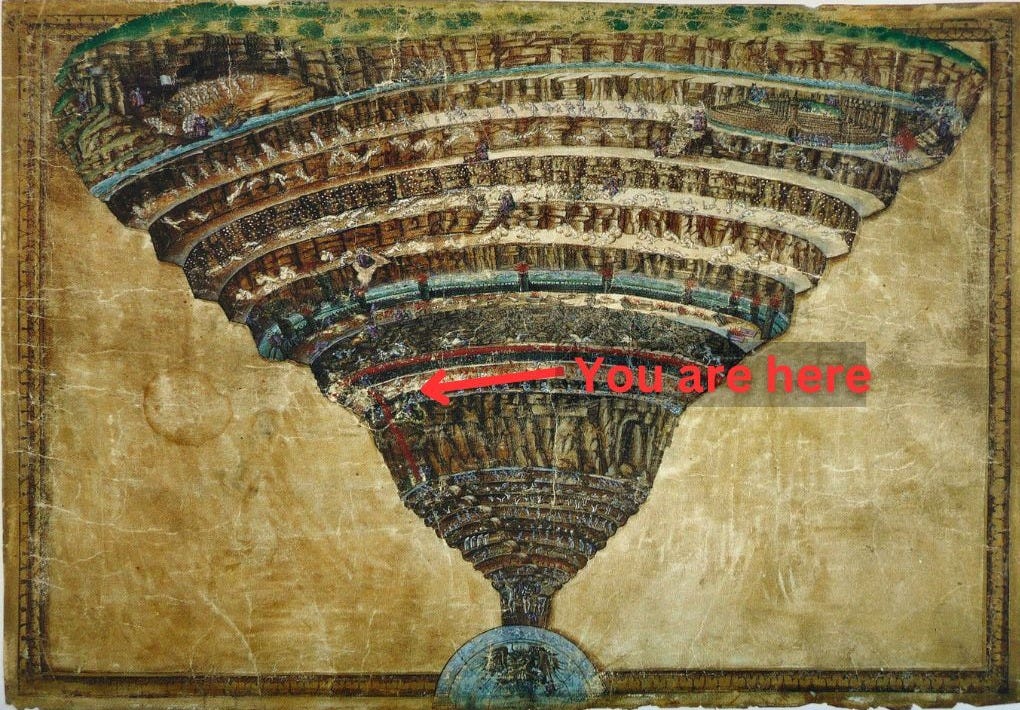

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Fifteenth Canto we see more of the burning sands of Violence against Nature. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

The Seventh Circle, Third Ring - Sinners against Nature - The channel of the River through the burning sand - The rain of fire - The Sodomites - Brunetto Latini, Dante’s mentor - A prophecy from Brunetto about his exile.

Canto XV: Summary

Still taking place in the third ring of the Seventh Circle, Canto XV begins in an atmosphere of protective mist coming from the river which shields Dante and Virgil from the falling flakes of fire. Dante describes the construction of the waterway, its course built as are the dykes of Flanders or the embankment walls of the river Brenta in Padua. They walk along this channel that crosses from the wood - now in the distance behind them - through the sands, the mist keeping them cool enough to be protected from the burning sand.

Dante would already know who was in this ring based on what Virgil had explained to him about the architecture of Hell in Canto XI, the Sodomites.

They came upon a group of souls who looked intently at the Pilgrim and the Poet ;

And each stared steadily at us, as in the dusk,

beneath the new moon, men look at each other.

XV.17-19

Of those who are gazing, one recognizes Dante and grabs his hem; he is below Dante within the lower level of the embankment, and since Dante was walking on the upper level, along the edge, the soul could reach up and grab his hem.

The burning landscape had made this man “baked and brown,” but Dante recognizes him as Ser Brunetto Latini (XV.31), Dante’s honored mentor in life. Latini lets his group move ahead and stays back to speak with Dante, and Dante says that he will stay and rest with him if Virgil will allow it.

But, Brunetto says, he cannot pause; if any of the souls in that realm stop in their march forward, they are bound in place for a hundred years, and cannot protect themselves from the raining fire. Brunetto invites him to walk along the lower path with him so they may speak, but Dante is hesitant to take the same path as those being punished (XV.43-45).

Brunetto asks Dante how he came to be there, and who it is that is guiding him.

‘There, in the sunlit life above’ I answered,

‘before my years were full, I went astray

within a valley. Only yesterdayat dawn I turned my back upon it--but

when I was newly lost, he here appeared,

to guide me home again along this path.’

XV.49-54

Brunetto responds with a speech; he says how much he believed in Dante and would have helped him had he lived. Brunetto makes the prophecy that the descendants of Fiesole will oppose him,1 but Dante can use it to his advantage, as “among the sour sorbs / the sweet fig is not meant to bear its fruit” (XV.65-66).

Dante, in his compassion at seeing Brunetto in the realms of Hell, wishes that he was not “banished from humanity” (XV.81), praising his memory, his influence, and that he taught Dante “how man makes himself eternal” (XV.85). This earthly fame and glory however is not what Dante was seeking, but a higher attainment.

Glory gives the wise man a second life; that is to say, after his death the reputation which remains of his good works makes it seem as if he were still alive.2

Dante expresses gratitude for Brunetto’s message, trusts him and takes his word, saying:

I will write down what you tell me of my future

and save it, with another text, to show

a lady who can interpret, if I can reach her

XV.88-90

The other text he refers to here is the political prophecy that he received from Farinata in Canto X about his exile; he will bring both of these with him to Beatrice.

Dante is confident that he will be prepared to meet Fortune, even though the wheel may turn as it will regarding the prophecies that Brunetto is making. Virgil, in his only line of speech in this Canto, turned to tell Dante “He listens well who notes well what he hears” (XV.99), seeming to say to Dante that while he may meet the Fortune that comes to him, it would also serve him to listen to the prophecy that Brunetto is giving him and gain by it.

Blessed is he that readeth, and they that hear the words of this prophecy, and keep those things which are written therein: for the time is at hand.

Revelation 1:3 KJV

Dante asks of others he may know in that realm, and Brunetto says that while their time is too short to speak of such things, he can name a few.

He names Priscian, a teacher and grammarian of the 6th century AD, and the author of a famous Latin grammar, the Institutiones grammaticae, as well as Francesco d’Accorso, a 13th century Florentine lawyer, who lectured both at Oxford and the University of Bologna, reportedly known for the practice of usury.3

The one the Servant of His Servants sent

from the Arno to the Bacchiglione’s banks,

and there he left his tendons strained by sin.

XV.112-114

This “one” is Andrea de’ Mozzi, the bishop of Florence. He was transferred out of his position in 1295 for “unseemly living;”4 the Arno refers to his bishopric in Florence, and the Bacchiglione’s banks refer to a river above the town of Vicenza, where he was transferred.

Brunetto asks Dante to remember his work the Tresor, or, The Book of Treasures; his major work was an encyclopedia of the sciences, ethics and rhetoric, and history. He sees a sign of smoke in the distance indicating a new group of souls approaching, and tell Dante that he must now return to his own group.

Brunetto ran, not as one condemned, but like the wind, as a winner in a race.5

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

Noble young man, make friends with the face of glory

And glorious applause,

And find how far loose lazing is surpassed

By hard-won honour.

~ To the Victorious by Giacomo Leopardi

Brunetto Latini was to the real Dante what Virgil was to the fictional one—a guide, a mentor, a source of wisdom. It was perhaps Brunetto, who induced Dante to read Cicero and Boethius, as he says he did, after the death of Beatrice. It is also possible that Brunetto was Dante’s guardian after the death of his father.6

Each encounter with a sinner in our journey has revolved around the sin that condemned them. In the circle of lust, Francesca recounted her tragic tale; Farinata, with unshaken pride, spoke of his defiance; Capaneus, even in torment, continued his blasphemous rebellion. Each sinner embodies their sin, their words and manner reflecting the very fault that cast them into the depths of Inferno.

With the previous sinners, one can discern the cause of their condemnation merely by attending to their discourse. Without Dante’s vivid descriptions of the surroundings, we might still infer what condemned Brunetto; yet the dialogue between Latini and Dante offers not even a hint as to the sin for which Dante’s mentor was condemned.

Or can we? Perhaps Cicero offers us a clue.

I. Fame is easy to reach. Immortality is reserved for the few.

When reading Brunetto’s words I felt as if I could hear his voice. His words, images, tone and wisdom had a resemblance that was way too familiar to my ear. It took me a couple of days to realise that his words resemble those of Cicero and Seneca.

This beautiful wisdom for example:

And he to me: “If you pursue your star,

you cannot fail to reach a splendid harbor,

if in fair life, I judged you properly;(55)

Seneca:

If a man knows not to which port he sails, no wind is favourable.

Although phrased differently, the meaning remains unchanged. We reach the same end by discrepant means, to borrow the phrase from Montaigne - who was also an avid reader of Seneca and Cicero.

Cicero, in his turn, offers a thought that may serve as a key to understanding the nature of Brunetto Latini’s punishment.

The great Roman orator wrote in his letter: “Fame is easily achieved, but immortality is reserved for the few.”

II. Don’t Chase Fame, Seek Immortality

Dante pays his debt to Brunetto. But what was it that Brunetto (or, more likely, his writings) taught Dante about immortality? Brunetto himself says that fame for good works gives one a second life on Earth.7

It means that your techne (art) is not aimed at virtue or grace but is aimed at preserving your name in the material world, the ephemeral, temporal world. For Dante, true immortality comes in the afterlife. For the Christian Dante this did not mean neglecting one’s affairs while being alive, but that one’s actions need to be charged by virtue, harmony, and divine love as well.

As Hollander mentions in his notes [Dante’s] heavenly reward might be combined with that one if his poem were, unlike Brunetto’s work, dedicated to a higher purpose.

For Dante, fame is merely the act of being at the center of public attention—of being spoken about, whether in praise or scandal. Some attain it by composing great poetry; others by shocking the masses with unexpected deeds. Yet to simply be discussed is not to be virtuous. A poet may craft a provocative verse devoid of spiritual essence, just as a bold action may stir the world while leaving behind only harm.

There is a debate among Dante scholars on whether Brunetto is punished for sodomy or for his obsession with obtaining a second life on Earth through his literary works. I will have to leave that debate for the more scholarly to resolve.

I must say however that Brunetto’s speech moved me and left me pondering upon the nature of mentorship and the difference between mere fame and true immortality. All sinners that Dante encounters, one way or another, want their name to be preserved and be remembered in the world of living. None of them, as none of us, want to vanish.

Dante knows that his readers have the same instinct and his message to us, as it seems to me is - mere fame, the act of being spoken about, is not enough. A fame should be intertwined with virtue, otherwise it is a hollow echo rather than a lasting legacy.

I would like to touch upon some ideas from Brunetto’s speech in the section of Themes.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Dante is Prepared for Fortune’s Challenges.

One thing alone I’d have you plainly see:

so long as I am not rebuked by conscience,

I stand prepared for Fortune, come what may.My ears find no new pledge in that prediction;

therefore, let Fortune turn her wheel as she

may please, and let the peasant turn his mattock.

Dante’s response to his mentor’s prophecy is charged with confidence, leaving one to wonder how much of it stems from Brunetto’s stirring and powerful speech, and how much arises from Dante’s reason slowly awakening as he descends deeper into the Inferno.

One more beautiful expression of wisdom from Brunetto:

and there is cause—among the sour sorbs,

the sweet fig is not meant to bear its fruit.

A bad tree cannot give birth to a sweet fruit and both Brunetto and Dante created their masterpieces while in exile.

What does it mean to have a true mentor?

I opened a journal from years ago, and found on its first page the words of Brunetto Latini to Dante:

If you pursue your star, you cannot fail to reach a splendid harbour.

I remember how deeply these words moved me when I first encountered them in one of the darkest depths of Inferno. A mentor is not merely a guide but one who directs the mind toward the stars. To discover the destination is already half the journey. A true mentor does not simply hand us a map to the stars; instead, they walk beside us, shaping the path together, an accomplice in our pursuit of higher ground.

Brunetto handed Dante two pencils with which to sketch his map—the wisdom of Cicero and Boethius. The rest was left to his student, who traced the path that we now walk together today.

Brunetto as a winner

And then he turned and seemed like one of those

who race across the fields to win the green

cloth at Verona; of those runners, heappeared to be the winner, not the loser.

There was an annual footrace in Verona, the contestants had to run naked and the winner would get a green leaf to cover his honour (the green cloth), whilst the loser had to walk into the city with a cockerel, as a sign of his disgrace.

I guess this is what happens when you don’t have YouTube Premium for your entertainment 700 years ago.

Dante’s final words reveal his true thoughts about his mentor. Though he places Brunetto in the Inferno, he still sees him as a victor, not a defeated man. Could the ‘green cloth’ that Brunetto covers himself with be his works—his intellectual legacy, his attempt at immortality through words?

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

Once again I will dare to include lines from another poet, a poet who is considered to be the second greatest in Italy after Dante himself. An excerpt from On Dante’s Monument by Giacomo Leopardi:

Are we forever lost?

Is there no limit to our shame?

I, while I live, will never cease to cry:

"Degenerate race, think of thy ancestry!

Behold these ruins vast,

These pictures, statues, temples, poems grand!

Characters:

- Brunetto Latini - (1220-1294) A Florentine Guelf, Latini was involved in public affairs, a mentor to Dante, and author of encyclopedic texts, such as the Tesor, and the poetry of the Tesoretto.

The inhabitants of Florence were thought to be of two groups. When Catiline fled Rome after his conspiracy of insurrection was discovered in 63 BC, he went to the city of Fiesole. There they were besieged by Caesar and defeated; the newly established Florence was a blend of the original Fiesole and the Romans who remained behind.

Singleton, Inferno Commentary 267 quoting Brunetto Latini’s work Tresor II.cxx.i.

Mandelbaum 580

Singleton 271

Bocaccio writes: I have heard that the Veronese observe an ancient tradition at one of their feasts. They have naked men run a race, and the prize is a piece of green cloth. For fear of being embarrassed, no one enters the race unless he thinks himself a very fast runner (Singleton 272).

Barbara Reynolds, Dante

Hollander, page 289

This substack is such a deep and precious gift. Thank you.

I so greatly appreciate Vashik’s learned and humane commentary. Thank you!!