Overcoming Nostalgia: "Salve Regina" and "Te Lucis Ante"

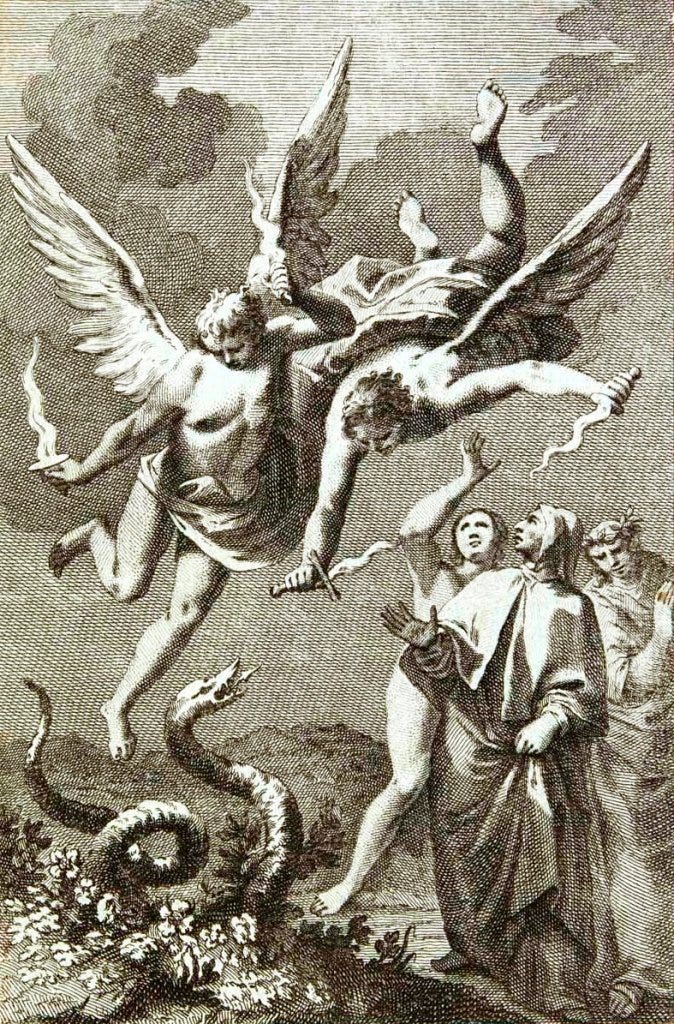

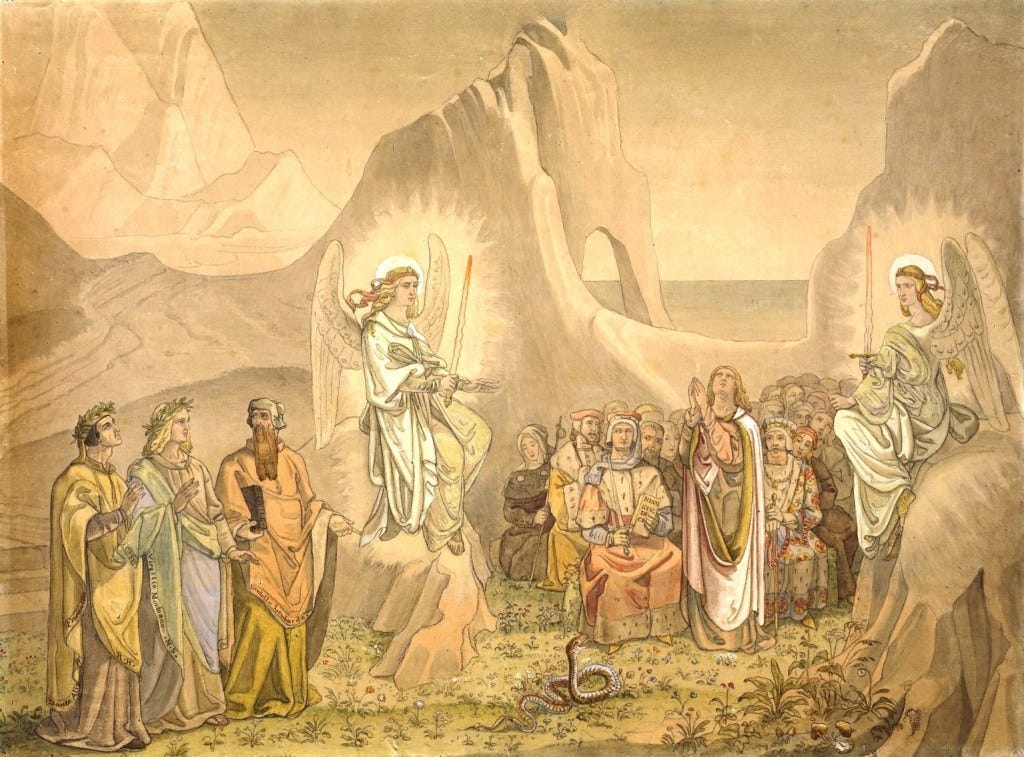

(Purgatorio, Canto VIII): Eve as Anti-Mary, Snake, and swords with broken tips

Wishing to all my readers:

“So may the lantern that leads you on high

discover in your will the wax one needs—

enough for reaching the enameled peak,”

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

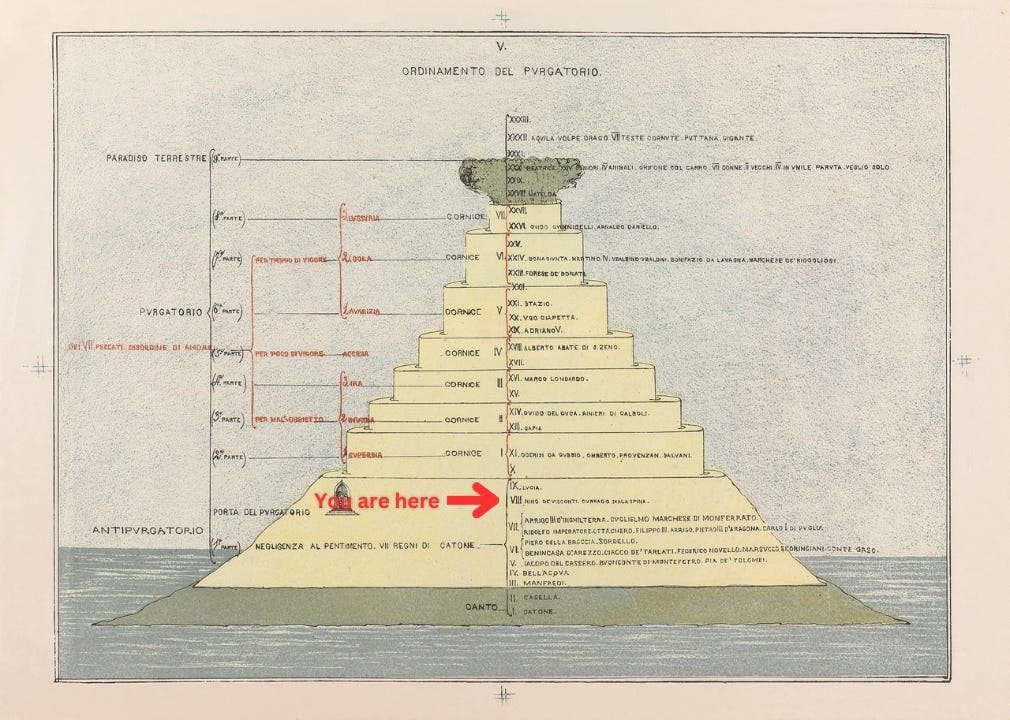

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Eighth Canto of the Purgatorio, we witness the drama of the Temptation. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

The longing of the evening - The compline hymn Te lucis ante - Angels descend from heaven - Their green robes and flaming swords - Descent into the valley - Nino Visconti - The drama of the serpent being cast away - Corrado Malaspina.

Canto VIII Summary:

Dante sang praise to the falling evening—just as he celebrated the breaking dawn in the first canto of the Purgatorio—with a song of longing, and with metaphors of the sea and of pilgrimage. Just as the sailor thinks of home as the first evening of his journey falls or the pilgrim feels his heart swell and melt as the sun sets on another day, so does Dante feel.

It was the hour that turns seafarers’ longings

homeward—the hour that makes their hearts grow tender

upon the day they bid sweet friends farewell;

the hour that pierces the new traveler

with love when he has heard, far off, the bell

that seems to mourn the dying of the day;

viii.1-6

Dante spoke of this very longing in his Vita Nuova:

Ah, pilgrims, moving pensively along,

thinking, perhaps, of things at home you miss,

could the land you come from be so far away

(as anyone might guess from your appearance)

that you show no signs of grief as you pass through

the middle of the desolated city,

like people who seem not to understand

the grievous weight of woe it has to bear?

Vita Nuova XL

Dante was no longer listening to Sordello, whose long speech on those in the valley of the princes closed out canto vii, but was watching a soul, unnamed, who gestured for quiet as he faced the east. Thus through his movements, did they all turn from the pre-occupied nature of their souls to a full attention to God. This soul sang the compline hymn of St. Ambrose, Te lucis ante; compared to the lamentation of exile of the Salve Regina, the Te lucis looked forward and asked for protection from danger:

Before the ending of the day,

creator of the world, we pray

that, with Thy wonted favor, Thou

wouldst be our guard and keeper now.

Dante was so moved by the beauty and sentiment of this hymn that he was “moved to move beyond” his mind into a moment of transcendence. The other souls present joined in to sing the hymn through, their eyes fixed on the orderly movement of the heavens; for those familiar with the rest of the prayer, it signaled what was to come:

From all ill dreams defend our eyes,

from nightly fears and fantasies;

tread under foot our ghostly foe,

that no pollution we may know.

Here reader, let you eyes look sharp at truth,

for now the veil has grown so very thin-

it is not difficult to pass within

viii.19-21

Dante also reminded us of this veil back in Inferno; in the depths of Hell it was dense and obstructed true vision, now it is growing ever thinner, transparent and more translucent:

O you possessed of sturdy intellects,

observe the teaching that is hidden here

beneath the veil of verses so obscure.

Inferno ix.61-63

As if their very prayer had summoned them, two angels “bearing flaming swords” (26) descended from the heavens; their swords had broken blades, symbolizing both justice—the sword itself—and mercy—the blunt tip that does not wound;

So he drove out the man; and he placed at the east of the garden of Eden Cherubims, and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life.

Genesis 3:24

The angels’ billowing green garments flowed as their green wings gently brought them down from above as the souls below gazed upon them lovingly.

Green is the color of hope, and the hope of those who have humility, who wait upon the Lord for protection, is not in vain. “Manna” descends, angels come, and as long as His angels are watching over us, and three stars shine down upon us, the dangers which beset our way cannot be such as to require sharp-pointed swords to drive them back, for swords can be as token swords where He guides. So much of the “truth” we are expected to see, if we sharpen our eyes.1

These angels flanked the souls on either side of the valley inside which they all stood, their brilliance in the dim evening shining so brightly that:

My eyes made out their blond heads clearly, but

my sight was dazzled by their faces - just

like any sense bewildered by excess.

viii.34-36

Sordello announced their descent was from Mary in heaven, and we find the first mention of a serpent which has been alluded to in the second verse of the compline hymn. Dante pressed closer to Virgil at the mention of the impending danger, but before it appeared, Sordello directed them to descend further into the valley.

Dante recognized, upon closer inspection in the shadows, Nino Visconti, rejoicing to find him in the blessed place of Purgatory and not in Inferno, paralleling the meeting and joy of Sordello and Virgil.

Nino was a Guelf of Pisa who had been exiled and had spent time in Florence, during which time it was likely that he met Dante. Nino’s grandfather was Count Ugolino, whom we met in Inferno XXXIII, he of the wretched story of starvation in the tower with his children and grandchildren and the horror of his punishment in feasting on his neighbors skull in the icy lake.

He asked Dante how long he had been in Purgatory, mistaking him for a shade, and when Dante corrected him and explained that he was still living, not only Nino but Sordello also, who up until now just assumed that Dante was a shade, both stared in amazement at the news.

Nino called to another soul, Corrado, to hear Dante’s story, and asked that Dante tell his daughter Giovanna, after returning to the earth plane, to pray for his soul so that he could move more quickly through Purgatory with the merit her prayers would bring to him.

He then seems to condemn the wife he left behind, Beatrice d’ Este, chastising her for taking another husband, Galeazzo Visconti of Milan—putting away the white veils of widowhood—for she will suffer exile herself with her new husband, and if she had stayed as she was, would be safer under his coat of arms; Nino said all this filled with righteous zeal.

The heraldic device of the Visconti of Milan was a blue viper swallowing a red Saracen, which, says Nino, will not be such a fine adornment on Beatrice’s tomb as his own device, the cock, would have been.2

Dante looked to the southern pole, the point at which the stars seem to move the most slowly, when Virgil asked what he was gazing at:

And my guide: “Son, what are you staring at?”

and I replied: “I’m watching those three torches

with which this southern pole is all aflame.”

Then he to me: “The four bright stars you saw

this morning now are low, beyond the pole,

and where those four stars were, these three now are.”

viii.88-93

The three “torches”, or stars, at which Dante is gazing contrast the four stars that they had seen that morning; the three represent the theological virtues of Faith, Hope, and Charity, while those they saw at Dawn were the four cardinal virtues, but which are now invisible to their sight; those that the souls in Limbo were proficient in; justice, prudence, temperance, and fortitude.

Sordello brought Virgil’s attention to the scene before them; a dramatization of the defeat of the Tempter was upon them. The serpent they had feared came along the valley, the embodiment of deceit like the tempter of Eve in the garden, slowly easing itself closer to them.

I did not see—and therefore cannot say—

just how the hawks of heaven made their move,

but I indeed saw both of them in motion.

Hearing the green wings cleave the air, the serpent

fled, and the angels wheeled around as each

of them flew upward, back to his high station.

viii.103-108

In what we can assume is a nightly drama of release from Temptation, the serpent is driven away.

Corrado Malaspina , whom Nino had called to to witness Dante’s living form, gazed intently upon the pilgrim during this action, and approached with a now familiar request; Corrado asked for news of home in Val di Magra. Boccaccio, author of the fourteenth-century Life of Dante, tells a story of Corrado and his daughter Spina in his Decameron, highlighting the fault that placed him in Ante Purgatory; the selfish love of his own family which caused him to become preoccupied away from his religious duties: “to my own I bore / the love that here is purified” (20-21).3

Dante praised Corrado’s family and lineage, noting it’s fame throughout Europe; here he makes a wish fulfilling promise;

And so may I complete my climb, I swear

to you: your honored house still claims the prize -

the glory of the purse and of the sword.

Custom and nature privilege it so

that, though the evil head contorts the world,

your kin alone walk straight and shun the path

of wickedness.

viii.127-133

Corrado gives Dante a prophecy regarding his exile; before seven years has passed, he will know of the generosity of the Malaspina family not only through hearing of it, but by experiencing it first hand in the assistance they will show to him during his exile, on one condition;

“If the divine decree has not been stayed” (139)

💭 Philosophical Exercises

TRUTH is within ourselves; it takes no rise

From outward things, whate’er you may believe.

There is an inmost centre in us all,

Where truth abides in fullness; and around,

Wall upon wall, the gross flesh hems it in,

This perfect, clear perception—which is truth.

~ Robert Browning, Paracelsus

Soft hour! which wakes the wish and melts the heart

Of those who sail the seas, on the first day

When they from their sweet friends are torn apart;

Or fills with love the pilgrim on his way

As the far bell of vesper makes him start,

Seeming to weep the dying day’s decay;

Is this a fancy which our reason scorns?

Ah! surely nothing dies but something mourns!

~ Lord Byron, Don Juan, Canto III, 108

Beckett and Borges, Hugo and Milton, Shakespeare and Chaucer: the list of geniuses Dante has inspired is endless. And from this canto onward, we can add one more name to that list: another Englishman - Lord Byron.

Just read the opening lines of Purgatorio Canto VIII and compare them to the lines Byron wrote above. The resemblance is striking - almost word for word.

At this point, I’m tempted to propose a new literary timeline: B.D. and A.D, or Before Dante and After Dante.

For consider this: Dante was shaped by nearly every great poet and thinker who came before him. In Inferno, we saw the towering presence of his influences: Virgil, Ovid, Horace, Boethius, Homer, Lucan, Aristotle, and more. The Divine Comedy is, in many ways, an encyclopaedia of the world’s philosophy, poetry, science, and literature woven together in a single, unified verse. This is what I call Before Dante.

What about After Dante? It becomes clear that nearly every literary genius who followed bears traces of his influence. Look at English literature: Shakespeare reveals Dantesque echoes; so does Milton; Chaucer - especially Chaucer - was profoundly inspired by him. Byron, as we now see, joins their company.

Turn to French literature: Hugo, Balzac, Baudelaire - all deeply indebted to Dante. Balzac even titled his life’s work The Human Comedy, portraying the Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso of his own time.

And let us not even begin with the Italians, who rightly consider Dante the father of their language and literary tradition.

Dante divided the literature of Christendom - particularly Latin Christendom- into what came before him and what followed. His fingerprints are everywhere, pressed into the pages of the great books we read today.

This is not simply my desire to praise Dante once again. Who am I to praise the greatest poet who ever lived? The geniuses I mentioned above have done that for me through the reverence they show him in their own works. Their admiration for the great Florentine speaks louder than mine ever could.

I begin this section of Philosophical Exercises with Dante because, in this canto, he does something extraordinary: he reverses time. Time, which was fractured and divided after the great transgression.

Let me show you what I mean…

I. From Hell to Eden

It was the hour that turns seafarers’ longings

homeward—the hour that makes their hearts grow tender

upon the day they bid sweet friends farewell;the hour that pierces the new traveler

with love when he has heard, far off, the bell

that seems to mourn the dying of the day;Purgatorio, VIII, Lines 1-6

Dante departs, but departs from where? From what state of heart and mind?

If we look closely, we can see that in this short canto, we see the reversal of the Fall of Eden.

After our ancestors tasted the forbidden fruit, whose mortal taste brought death and all our woe into the world, they were exiled from the garden of Eden, from Paradise, and descended into what one could perhaps describe as Inferno. Paradise Regained could happen only through our hard effort: by descending into Inferno and climbing the mountain of Purgatory.

So, the timeline is such: Paradise → Serpent → Taste of the Forbidden Fruit → Exile

(In the Themes section, I also explore Eve as Anti-Mary)

Dante’s journey follows the reverse timeline—as Dante’s genius changed literary time, so did the great Florentine in his masterpiece reverse the fall of humankind:

Inferno (loss of good way) → Regaining Reason by crossing Inferno → Canto VIII seeing serpent again → about to enter Purgatory

It is fair to say that Milton’s Paradise Lost and Dante’s Divine Comedy explore the human psyche from different ends, in a different order of events.

But, let us look at this even closer…

II.

I told him, “Oh, by way of the sad regions,

I came this morning; I am still within

the first life—although, by this journeying,I earn the other.” When they heard my answer,

Sordello and Judge Nino, just behind him,

drew back like people suddenly astonished.(lines 58-63, Mandelbaum)

It’s only around the middle of this canto that Dante steps back into the spotlight as the central figure of the poem. Until then, it was curious (and telling) to see him fade into the background while Sordello explained to Virgil the nature of divine and cosmic order.

Boethius once wrote that reason must be wedded to faith, and there’s no doubt that this union has been quietly unfolding across the last two cantos.

Virgil, who ruled with authority in Inferno, now finds himself on less certain ground. In Purgatorio, he falters at times, reacts more slowly than expected, and must learn to navigate unfamiliar terrain. For the pagan guide, these are uncharted landscapes lit not by reason alone, but by grace.

This moment marks a key turning point—the true beginning of the reversal of time. Our pilgrims witness the appearance of two angels with fiery swords, the very same kind of angels God placed to guard the gates of Paradise after the Fall.

But here, their swords are symbolically different: the tips are broken, and the flames they emit are not those of wrath or punishment but of divine love and mercy.

What unfolds next is equally striking. The serpent appears, an echo of Eden’s original deceiver, and Dante, so intensely focused on the creature, fails to notice the angels silently gliding toward it.

It feels as though the Boethian idea that reason must be married to faith has come to life in Dante’s narrative. This may be why Virgil stepped into the foreground in the past two cantos, playing a more central role. In these moments, reason was still guiding the way, interpreting the new terrain of the soul with careful steps.

But if we translate this into more secular terms, we might say that what ultimately protected Dante wasn’t reason alone, it was something closer to intuition. A deep inner sense that arises when one has mastered something so completely, it begins to move through you effortlessly, like a skilled sailor who can sense a storm before it hits the sides of his ship. It is a sense that comes not only from calculation but from deep experience and understanding, when the reason and soul have learned to read the world without needing to think.

III.

While revisiting my notes recently, I came across a beautiful quote in The Visionaries by Wolfram Eilenberger, one that I believe resonates deeply with the themes of this canto:

As a philosopher and journalist, Weil could see only one genuine way out of this crisis that would heal civilization, rather than return to the things themselves. In her view, humanity had to return to the sources themselves. She understood committed readings and re-readings of the great source texts of humanity, like an archaeologist, revealing layer by layer those values and primal impulses that had been so plainly scattered and repressed.

After her own experience of transcendence, for Simone Weil, the unequal battle against the political realities of her own time could be fought only by regaining the divinely inspired fundamental values set out in the most ancient testimonies and epics of classical high cultures.

These were in particular the works of Plato and Homer, the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita, as well as the texts of the Stoics and the Evangelists.

They were all, in Weil’s view, ultimately inspired by the same light, which fanned out only spectrally in different ways according to the era and culture that had shaped the consciousness in question.

I’ve written briefly about Simone Weil here, so forgive me for not elaborating on why her genius matters so profoundly. But I couldn’t help noticing how the theme of this quote echoes Dante’s journey, from Inferno back toward Paradiso. Weil’s own path was one of return: a return to the roots, to the original sources of truth.

During her lifetime, Weil witnessed how the organized state could strip away individual identity. She lived through the rise of the moustached men, both the one whose name begins with H and the one with S, and she asked a haunting question: How can the individual survive in a world dominated by mass movements, crowds, and overpowering ideologies?

Her answer was simple, yet radical: go back to the roots—to the first sparks that once moved the human soul. This is not unlike what Dante does in the Divine Comedy. He journeys from the disordered depths of Inferno back toward the original light, the first hints of Paradise.

And in this canto, we see him cross a new threshold. This is where the reversal of time begins.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. Past against the Future: “Salve Regina” vs “Te Lucis Ante”

Robert and Jean Hollander beautifully observe the meaning behind the song Salve Regina, which was sung in the previous canto, and Te Lucis Ante which was witness here.

Perhaps it’s worth quoting Hollanders in full:

“Te Lucis Ante”, an evening hymn, is sung in its entirety, as opposed to “Salve, Regina”, which looks back upon the sadness of sin and exile, hoping for Marian intercession, “Te Lucis Ante” looks ahead and requests the Father's and the Son's protection from the dangers of the satanic forces of the night. Thus, while surely there is nothing wrong with singing “Salve Regina” in this context, it is time to turn to the future, and this is what the protagonist does.

~ Hollander, Purgatorio VIII, 175

II. Serpent’s Lick

At the unguarded edge of that small valley,

there was a serpent—similar, perhaps,

to that which offered Eve the bitter food.Through grass and flowers the evil streak advanced;

from time to time it turned its head and licked

its back, like any beast that preens and sleeks.(Lines 97 -102)

The snake indulges in self-love even during this brief appearance. I found this to be a beautiful (though chilling) description of it. How much one can say in so few words!

III. Reversal: Eve as Anti-Mary

There is an interesting parallel between Eve as Anti-Mary. If Eve plucked the forbidden fruit and gave it to Adam, Mary, on the other hand gave birth to Christ thus re-directing humanity back to the lost Eden.

There is a prophecy in Genesis that explores this:

Genesis 3.14 - 15, God's curse upon the serpent and the conjoined prophecy of the woman's seed who will bruise the serpent's head and have his heel bruised as a result, taken by Christian exegetes and surely by Dante among them, to refer to the crucifixion.4

I founds this to be another beautiful parallel!

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

I wish this to all of us, not only throughout this read-along, but throughout this read-along.

So may the lantern that leads you on high

discover in your will the wax one needs—

enough for reaching the enameled peak.(112-114)

Charles S. Singleton, “In Exitu Israel de Aegypto” 181

Singleton, Commentary on Purgatorio 169

Boccaccio, Decameron ii.6

Robert and Jean Hollander, Purgatorio 176

Really loved the way Dante opened this Canto. Just beautiful.