What Did Dante Really Think of Free Will?

(Purgatorio, Canto XVI): Wrath, Smoke and Marco

Our minds bear the same relationship to God, as our sight to the light of the Sun.

~ Marsilio Ficino

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

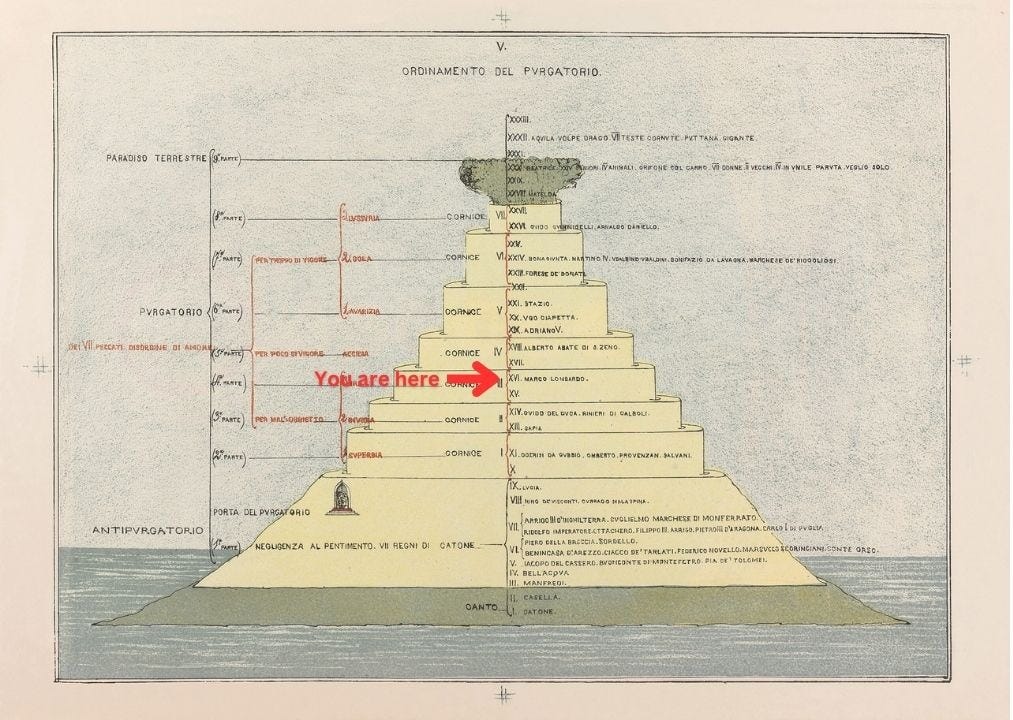

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Sixteenth Canto of the Purgatorio, Dante hears an exposition by Marco of Lombardy in the smoke of Wrath. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

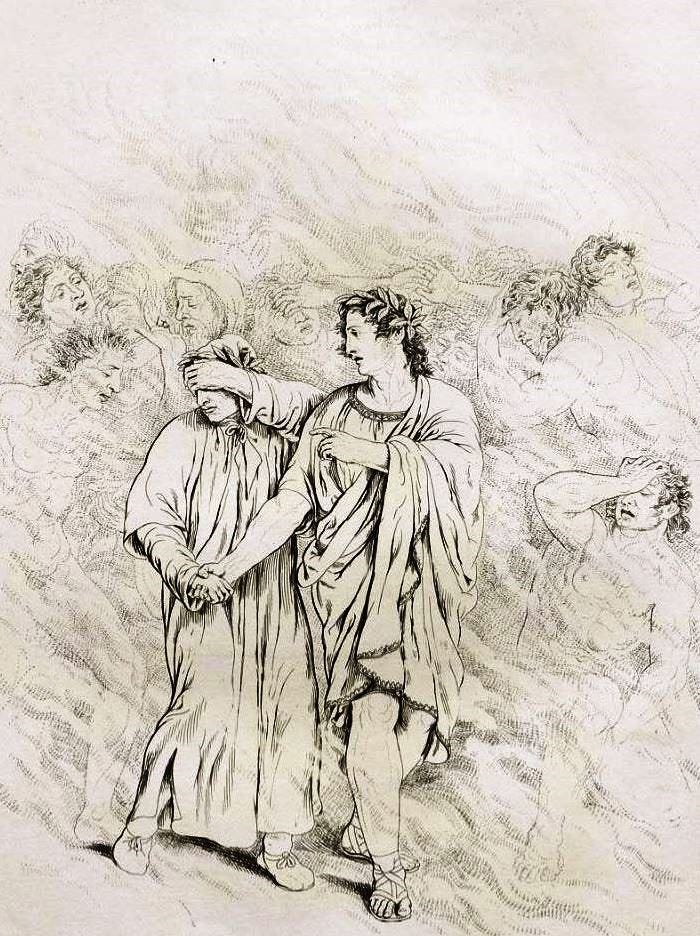

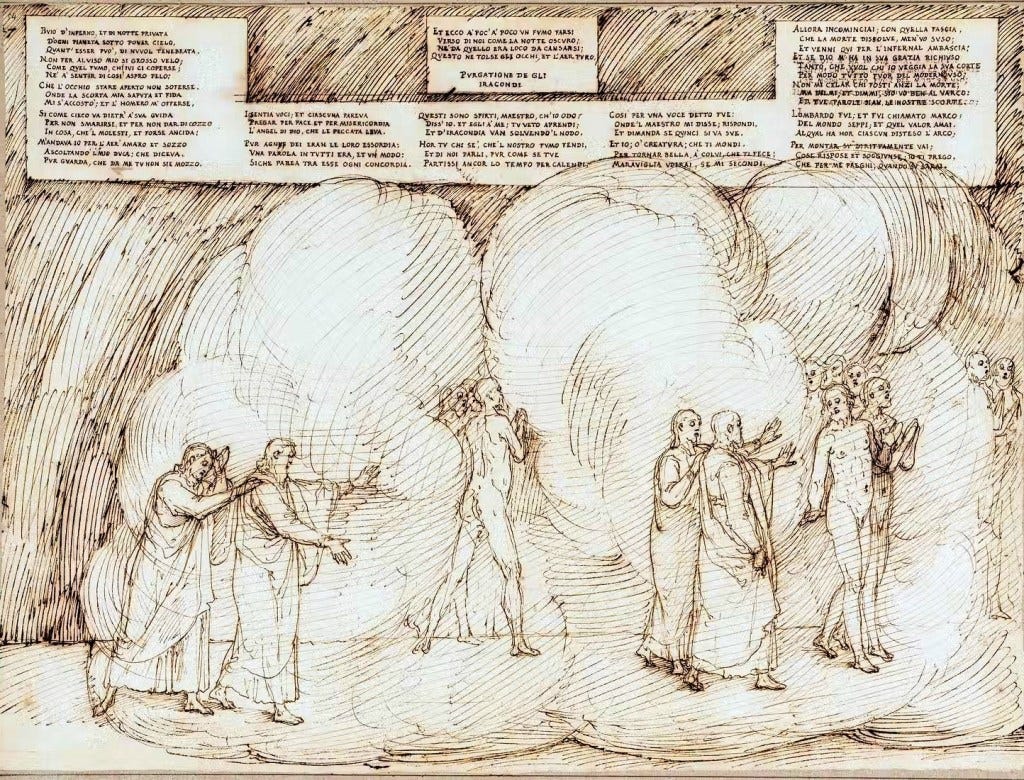

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Dante and Virgil enveloped by thick smoke - Prayer of Agnus Dei - The Wrathful of the third terrace - Marco of Lombardy - Philosophical and theological discussions - Astral influences, free will, church and empire - The smoke begins to clear - Marco departs.

Canto XVI Summary:

So thick and dense was the smoke that enveloped Dante and Virgil that no other darkness— not even the darkness of Hell, which Dante would know all too well—could compare to the stinging veil that it cast over them. Blinded, Dante drew close to Virgil—who, though he also was clouded over, was still able to guide Dante forward

Virgil as a wise guide has a way of ‘seeing’ that is not purely physical and accordingly can lead Dante on around the terrace.1

Just as a blind man moves behind his guide,

that he not stray or strike against some thing

that may do damage to-or even kill-him,

so I moved through the bitter, filthy air,

while listening to my guide, who kept repeating:

“Take care that you’re not cut off from me.”

xvi.10-15

Under these conditions, they heard the prayer of this third terrace, the prayer of the Wrathful. The voices sang in unison, in beautiful purgatorial harmony, the Agnus Dei, or Lamb of God; for the Wrathful to pray for peace, to the meek spirit of the Lamb, is fitting.

Agnus Dei qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis, dona nobis pacem.

O Lamb of God, that takest away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us; grant us Thy peace

Prayer of the Canon of the Mass

As Dante listened, he asked Virgil if they were hearing souls singing, as he still could not see through the thick smoke. Virgil named the sin of this terrace; those who aim to “loose the knot of anger” (24), to fulfill that debt of punishment.

The effect of Wrath is to blind the judgement and to suffocate the natural feelings and responses, so that a man does not know what he is doing. The penance of the Wrathful is therefore, once again, the endurance of the sin itself. Dante habitually connects Wrath with images of smoke and suffocation-reference the Sullen Wrathful in the fifth circle of Hell, whose “hearts smouldered with a sulky smoke,” and whose punishment is to lie gurgling and choking in the muddy bed of Styx.2

A single voice called out to them, if not able to see Dante directly, then seeing the change in that texture of smoke as Dante’s living body passed through it—the spirits then must not affect the texture—and knew also that he was different because he did not speak in the timeless manner of the afterlife, but like “a man who uses months to measure time” (27).

The dead know no division of time, since time does not pass for them.

Benvenuto, Comentum Super Dantis Aligherii Comoediam

Virgil encouraged Dante both to answer his question, and ask the right way of ascent up the mountain. Dante asked the soul to follow him, but learned that the soul could only come with them so far, and that even if they could not see each other, they could hear and communicate. Dante explained his journey and pointed out his path to see God’s “court” was not a common one for mortals to make:

Paul was caught up to Heaven and saw God’s “court,” and other contemplatives also had that experience in some measure, as the reader will learn in Paradiso. But the reader will also learn there that the upward way, the ladder, of contemplation which reaches to Heaven has been abandoned in modern times.3

The soul introduced himself as Marco, who proved to be an exemplar—even in his purgatorial state—of an old order of nobility, a higher standard than what Dante knew in the society of his day. Marco knew the workings of the world and yet still “loved those goods / for which the bows of all men now grow slack.” (47-48); that bow signifying the steady aim toward the thing desired; while those in Hell aimed it at selfish longings, here we find it aimed, even if not yet perfected, at higher goods.

Of Marco Lombardo not much is certainly known. Most of the old commentators agree that he lived at Venice in the thirteenth century, and was a man of great courtesy, generosity, and nobility of mind, though of a peppery temper.4

Marco pointed out that they were headed in the right direction, and asked for prayers of intercession when Dante returned to the world of the living. Dante took an oath, a pledge to do so, and opened up a conversation which would continue nearly through the end of the canto; as we saw with Guido del Duca in the last terrace, these questions were opportunities to expound upon philosophical and theological truths, as Dante saw them. Dante asked a question that opened up the very foundation of the understanding of free will.

And I to him: “I pledge my faith to you

to do what you have asked; and yet a doubt

will burst in me if it finds no way out.

Before, my doubt was simple but your statement

has doubled it and made me sure that I

am right to couple your words with another’s.

xvi.52-57

This doubt of which he spoke was one that came to him in the second terrace of Envy as he spoke with Guido del Duca on the wickedness of the world,5 especially those regions in Italy that Dante and Guido both were so invested in, their homeland; this was his simple doubt. Marco’s words, when he spoke of “those goods / for which the bows of all men now grow slack” (47-48), had doubled Dante’s doubt, by joining the two prospects together and creating a bigger set of questions than he had before. Whereas in his conversation with Guido, he saw the loss of virtue just in his region of Italy, now he was thinking of the loss of virtue in general in all of humanity, and on a different scale than just societal unrest.

The world indeed has been stripped utterly

of every virtue; as you said to me,

it cloaks-and is cloaked by-perversity.

Some place the cause in heaven, some, below;

but I beseech you to define the cause,

that, seeing it, I may show it to others.

xvi.52-54

If the world is stripped of virtue, “pregnant within and covered without”6 with evils, then why is this so? Dante needed to know clearly this vital truth so that he could share it, both in poetry and on his return to the living. Did the cause come from a mechanical determinism, from a fate set by destiny, the stars, and astral influence? Or was the reason solely to be found on the material plane of earthly life?

Marco sighed, as if to show that he too, had thought deeply about these things, and had come to a solution to the problem. Here begins “the first great Discourse on Free Will,”7 and Marco’s extended speech covers lines 65-129.

You living ones continue to assign

to heaven every cause, as if it were

the necessary source of every motion.

If this were so, then your free will would be

destroyed, and there would be no equity

in joy for doing good, in grief for evil.

xvi.67-72

Marco explained first that the living assume that astral influences affect humanity to the point that celestial forces are responsible for every action in personal and social affairs; but if this were so, there would be no room for free will, and would also cancel out even the need for the rewards of heaven and hell. The writers of the early and high middle ages had much to say about these influences.

Here and elsewhere it has to be borne in mind that Dante’s talk about the stars should not be summarily dismissed as ‘mere astrology’ or ‘medieval superstition’. When he speaks of the stars as the sole origin of causation he means by that exactly what the modern determinist means by saying that all events in the universe, including human behaviour, follow each other in inevitable sequence as the result of the physical interaction of the atoms composing it.8

And, what is more horrible, certain astronomers, crudely prophesying, declare that to be of necessity which in truth ye, making ill use of the liberty of the will, have rather chosen.

Dante, Epistole xi.4

The second error is that of necessity determined by fate, as influenced by the stars; thus, if a man was born under a certain star, he will inevitably be a thief, whether he be good or bad. This view destroys free will as well as merit and reward, for, if a man does what he does under compulsion, what good is freedom of choice? What merit can he gain?

Bonaventure, Seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit viii.18

Whatever by nature has the use of reason has the power of judgement to decide each matter. It can distinguish by itself between what to avoid and what to desire.

Boethius, Consolation of Philosophy v.1

Marco then set the stage for the true interpretation of astral influence, not as an end in itself, but only as a starting point; to say that astral influence was the sole determination of actions was denying both reason and judgement; yet this takes strength and practice to both right the disordered action and to stay on a firm path of right action. Perhaps it is in this way that Dante blended theology and astrology as he understood them to be compatible.

The heavens set your appetites in motion-

not all your appetites, but even if

that were the case, you have received both light

on good and evil, and free will, which though

it struggle in its first wars with the heavens,

then conquers all, if it has been well nurtured.

xv. 73-78

Even if the astral influences can affect our tendencies, as Dante believed, they are not firm and fast in that influence unless one lets them be; that ‘light on good and evil’ is the rational discernment that comes with sound judgement. To fight back against our own disordered inclinations and passions, as influenced by the astral tendencies, is the mark of philosophy in practice, and it is the sage who overcomes by this nurturing of order and exercising right choices.

Hence the heavenly bodies cannot be the direct cause of the free will’s operations. Nevertheless they can be a dispositive cause of an inclination to those operations, in so far as they make an impression on the human body, and consequently on the sensitive powers which are acts of bodily organs having an inclination for human acts. Since, however, the sensitive powers obey reason, as the Philosopher [Aristotle] shows, this does not impose any necessity on the free will, and man is able, by his reason, to act counter to the inclination of the heavenly bodies.9

The will can tend freely towards various objects, precisely because the reason can have various perceptions of good. Hence philosophers define the free will as being a free judgement arising from reason, implying that reason is the root of liberty.10

Wherefore be it known that the first principle of our freedom is freedom of choice, which many have on their lips but few in their understanding. For they get as far as saying that free choice is free judgment in matters of will; and herein they say the truth; but the import of the words if far from them, just as is the case our teachers of logic…therefore I say that judgment is the link between apprehension and appetite.

Dante, De Monarchia I.xii.2-4

When the free will is reigned and nurtured and all the actions are beneficial, doing no harm, that is when the expression of true freedom is manifested;11 when the soul is acting in accordance to its pure state (which we will find, through Paradiso, is love), then on the strength of that action, the celestial forces lose their influence to make one act blindly due to inherited traits; then, one can weed out the traits that are not of good influence and even choose to keep those traits that are beneficial to the character.

Marco, “a true investigator and informant,”12 is eager to lay out these foundational ideas upon which so much else leading upward in the Purgatorio and into Paradiso will depend; through him, Dante is weaving the fabric of his world view and philosophy, without which, the greater meaning of this poem as a whole would not be as accessible. He began to speak of the idea that a “free will [is] subjected to a higher authority,”13 and that without that willing subjugation, the greater social structure of government and politics cannot function for the best.

On greater power and a better nature

you, who are free, depend; that Force engenders

the mind in you, outside the heaven’s sway.

Thus, if the present world has gone astray,

in you is the cause, in you it’s to be sought;

and now I’ll serve as your true exegete.

xvi.79-84

They alone are free who of their own will obey the law. Dante, Epistole vi.23

Marco described the nature of the soul as being like a child, running this way and that after its own inclination, looking to trivial joys which may seem innocent, but end up beguiling, or deceiving the senses. Here is where the “guide or rein” becomes necessary, and in this example, Marco pointed to social laws that will help bring this order to the outer world; we have already seen what brings order to that inner world. Without a just ruler who could impose such order—in fairness, not in control—the foundations of society would collapse, which is what we saw in Dante’s conversation with Guido, that “first doubt”; the true city of which he spoke is the ordered city.

The goal, or ‘city,’ for mankind collectively is universal justice, which under the perfect rule of the monarch should prevail, and is synonymous with temporal felicity, the goal to which the emperor is ordained to lead…This ‘true city’ should not be understood as the eternal happiness in Heaven mentioned in De Monarchia, since it is the Church that leads to the heavenly goal. Here it is strictly a question of guidance by the emperor, who leads to a temporal goal.14

The laws exist, but who applies them now?

no one-the shepherd who precedes his flock

can chew the cud but does not have cleft hooves;

and thus the people, who can see their guide

snatch only at that good for which they feel

some greed, would feed on that and seek no further.

xvi.97-102

Marco acknowledged that the laws were in place for an ordered society as Justinian had placed them,15 and yet now, there was not a just ruler to enforce them; more than that, he used a cryptic analogy of a shepherd who could “chew the cud but does not have cleft hooves” (99).

Spiritual rule is symbolized by ‘chewing the cud,’ which had come to signify meditation, and temporal rule by ‘having cloven hoofs,’ signifying the making of distinctions, in an established allegorical interpretation of Leviticus 11:3: “Any animal that has hoofs you may eat, provided it is cloven-footed and chews the cud.” The pope confounds the two rules or divinely ordained governances by usurping the office of temporal guide without being a competent horseman who holds the reins in his hands, i.e., who enforces the law, for that is not his proper office.16

If the people’s own spiritual leader was chasing the riches and power the world had to offer, so much more would his flock chase after those same things, thinking that they are sanctioned by his example. The pope, in taking on temporal as well as spiritual power, was misleading not only Italy, but their greater world.

For Rome, which made the world good, used to have

two suns; and they made visible two paths-

the world’s path and the pathway that is God’s.

One has eclipsed the other; now the sword

has joined the shepherd’s crook; the two together

must of necessity result in evil.

xvi.106-111

Rome, under Justinian, had two suns; the temporal power of the emperor and the spiritual power under the pope, independent of each other; now that the temporal had joined the spiritual, no good could come of it.

Dante argues against those who interpreted the sun and the moon made by God to mean, allegorically, the two regimens, the spiritual and the temporal, the Church and the empire, for he would have had the moon stand for the empire and therefore have no light except that from the sun. This was a standard allegory widely accepted and debated. The poet’s image of “two Suns” is highly significant against such a background, for he has thereby affirmed the independence and autonomy of empire and Church.17

Marco shifted ideas here and looked to the region in northern Italy where old standards of nobility and justice once held sway; that is, until the time of the death of Emperor Frederick II. Now, however, rest assured, there is not a noble nature to be found.

The object of Frederick was to make of Italy and Sicily a united kingdom within the Empire. The settled purpose of the Papacy, supported by a revived and enlarged league of Lombard towns, was to frustrate this design. In the end the Papacy won the battle. The man was defeated by the institution, and with him passed away the last chance of an effective Roman Empire in central Europe or for many centuries of a united Italian kingdom.18

Marco called out the names of three famous exemplars of this old nobility still living in the year of the poem, 1300; they rejected the current standard of unrest and malcontent, even to longing for a release of life into Heaven to escape the misfortunes of their day. These are Currado da Palazzo, Gherardo and Guido da Castel; Dante mentioned Gherardo in his Convivio as an example of virtue, and Castel was known to have been a guest of Dante’s patron, Can Grande della Scala.

In closing, Marco declared the truth of his statements and proclaimed that the Church had defiled herself by falling into filth; she not only defiled herself, but also the temporal powers from which she was attempting to wrest powers. There was no winner in this battle.

“Good Marco,” I replied, “you reason well;

and now I understand why Levi’s sons

were not allowed to share in legacies.

But what Gherardo is this whom you mention

as an example of the vanished people

whose presence would reproach this savage age?”

xvi.130-135

The sons of Levi, the secondary ministers of the temple of the Hebrews who helped the high priests, descendants of the sons of Aaron, were not allowed to inherit wealth or property; as they were supported by offerings, it was better to avoid the temptations of wealth so that they did not fall into the corruption that stems from it.

When Dante asked Marco to clarify who Gherardo is, in surprise that Dante did not recognize the name, mentioned that he was also known as Gaia’s father. Most commentators point to Gaia’s infamy for promiscuity, even as her father was the most noble, showing how in one generation the decline of society had already taken root; yet one mentions another quality that brought her fame, her beauty and virtue:

Gaia was a beautiful and well-mannered girl resembling her father in almost everything. Anonimo Fiorentino

They approached the edge of the choking smoke, enough to be able to see light coming through; unwilling to let the approaching Angel see him, as he had not yet fulfilled his purgatorial duty and needed to remain within the smoke, Marco departed.

💭 Philosophical Exercises

You say: I am not free. But I have raised and lowered my arm. Everyone understands that this illogical answer is an irrefutable proof of freedom.

~ Leo Tolstoy

Umberto Eco, once wrote:

I believe that what we become depends on what our fathers teach us at odd moments, when they aren't trying to teach us. We are formed by little scraps of wisdom.

My father, who is largely responsible for this read-along, as he was the one who first introduced me to Dante, once told me that a parent can call themselves successful only when their child is able to make virtuous decisions without needing their parents’ guidance.

It was only later at “odd moments”, as Umberto Eco might have said that I began to notice my father’s quietly Dantean way of raising me.

Dante believed that vice stems from disordered perception, from misplaced love, and from the inability to adjust one’s sails toward the right destination. And like Dante, my father believed that the highest form of guidance was to teach me how to guide myself, to choose the books that would aid in my ascent. The kind of volumes that serve as stepping stones, strong enough to bear your weight as you move toward the next stage of your being.

He believed that if I could learn to seek the right path on my own, if he could teach me how to learn, he had done his part.

It is, after all, a parent’s duty to raise a child who can act virtuously, independently.

I. 'The Case of Benevolent Kidnapper’

Now, let’s consider the reverse.

What happens when guidance becomes control?

Imagine being kidnapped, strangely enough, by a good person. This ‘benevolent kidnapper’ forces you to do good deeds against your will: give money to charity, care for the sick, forces you to tell truth. You have no choice but to perform good deeds.

You perform these tasks, you give huge sums to the poor, and help those with ill-health, but could you call yourself in such scenario a good person?

I would assume, my reader’s answer is ‘no’ since you did not choose to do any of this.

It appears that we can only truly claim ownership of our actions when we possess the capacity to choose our course of action.

In Dante’s vision, those consumed by vice are like travelers following a broken compass. The souls in Inferno are damned not merely for their sins, but because they insist their compass is intact. They refuse correction, reject dialogue, and cling to their distorted sense of direction.

The souls in Purgatorio, by contrast, are there to repair it and to reorient their inner compass toward true north once more.

II. Don’t Assign Your Destiny to the Stars

You living ones continue to assign to heaven every cause, as if it were the necessary source of every motion. If this were so, then your free will would be destroyed, and there would be no equity in joy for doing good, in grief for evil. The heavens set your appetites in motion— not all your appetites, but even if that were the case, you have received both light on good and evil, and free will, which though it struggle in its first wars with the heavens, then conquers all, if it has been well nurtured.

There are several cantos in the Commedia that I love; one of them was when Dante meets Brunetto Latini, who tells us if we pursue our star, we won’t fail to reach a splendid harbour. Another favourite of mine is of course when we meet Ulysses, who tells us how to seek light at the edge of the known world.

This canto stands firm in the pantheon of my favourites, for the words of Marco reveal to us so much about how we reduce our lives to worthless existence by denying any responsibility for it.

There are many things in life that lie beyond our control. We do not choose when we are born, to which parents, on which continent, and even our own name is given to us.

Marco reminds us that the heavens may set our appetites in motion. However, there is a domain within us, a realm both Aristotelian and Augustinian, that not even God intrudes upon: our will, our conscience, our mind.

We are all born with free will, but like a muscle, its strength depends on how well it is trained.

Just as both I and an Olympic athlete are born with the same basic anatomy, it is the years of discipline and practice that make us incomparable. So it is with the will - its power lies not in its mere existence, but in how we shape and strengthen it.

How does one strengthen their will?

Nietzsche wrote that (one of the many aspects) of decadence is inability to resist stimuli, one is constantly driven by impulses, in multiple directions. You will always have impulses, as Nietzsche observes, but having free will means that you can arrange your impulses in order directed towards a goal.

I guess geniuses think alike, for what else is Dante’s journey?

It began in the depths of decadence, in disordered impulses and lack of goals. I particularly like Robert and Jean Hollanders’ translation of the verses:

'... and you have free will. Should it bear the strain in its first struggles with the heavens, then, rightly nurtured, it will conquer all.

“Rightly nurtured” and “in its first struggles with the heavens” - Dante and Nietzsche tell us that while the heavens roll the die of where our life journey begins, it is in our free will how it will unfold.

III. Dante and Milton

We will explore the concept of free will more deeply in Paradiso, where Beatrice will illuminate how the all-powerful Divine still grants us the right to choose.

But here, I’d like to pause and highlight one more important distinction, namely, the difference between Dante and Milton.

As you can plainly see, failed guidance is the cause the world is steeped in vice, and not your inner nature that has grown corrupt.

These lines (103–105) come from Robert and Jean Hollander’s translation, and I love how Marco tells Dante that our inner nature is not corrupt in itself. It is disorder within that gives rise to vice.

You cannot blame the seed of a beautiful flower for failing to grow if it was planted in barren, uncultivated soil.

In Dante’s view, we reach the Divine way of life by placing ourselves in order—by aligning our loves, desires, and reason in harmony. For Milton, however, the vision is slightly different. He sees the inner world as a battleground between loyal and rebel angels. The fall of Lucifer is not only a cosmic event, but one that unfolds within each of us and the clash continues, endlessly, in the depths of the human soul.

IV. Not so famous last words

I am profoundly moved by this canto. The idea of free will interests me since I see the consequences when some people accept it and when some people reject it in real life. Our capacity to come up with the very concept of free will (the power of acting without the constraint of necessity or fate) is fascinating in itself.

If we invent words to describe the reality around us, if we see a rock and create a word so that someone who cannot see it might still understand, then is free will perhaps something similar?

An invisible reality within us that we have named, not invented, because we have experienced its presence?

In that case, those who reject the idea of free will might resemble someone untrained in a discipline, trying to convince an Olympic athlete that lifting heavy weights is impossible, simply because they themselves have never trained, never tried, never discovered that inner strength.

Is this the reason why this concept is explored in a canto where the sight prevails?

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. Smoke and Sight

If the envious are blinded to the world so they may look inward, the wrathful are blinded by their rage. They see nothing beyond themselves.

It is interesting to see how Dante explores the function of sight, for seeing only your inner landscapes is different from not being able to see landscapes that surround you. Smoke has a particular meaning here - in your wrath you obfuscate your ability to see anything beyond yourself, but here is a catch: in Inferno the punishments were designed in contrapasso, here in Purgatorio, punishments aim at purifying the soul.

When you are consumed by wrath, you lose sight of your immediate surroundings. Your focus narrows, fixating entirely on the object of your anger while everything else fades away.

Here, Marco can only see the present moment. His vision, unlike the wrathful, is not clouded by fixation but grounded in clarity. And fittingly, he speaks of free will, which exists only in the here and now19 in the choices we make in each passing moment.

II. Church and Empire

You can conclude: the Church of Rome confounds

two powers in itself; into the filth,

it falls and fouls itself and its new burden.

These lines deserve further explanation, but what I want to draw my reader’s attention to is a broader misconception. Medieval times are often portrayed as a kind of Stalinist authoritarianism: an era of rigid control, silencing of dissent, and blind obedience.

And while it’s true that the period was marked by persecution and the consolidation of institutional power, I’m often struck by how boldly and unapologetically Dante criticizes the Church and the Popes. His critique is not mild,it is sharp, at times even violent.

Dante lived within the system, yet dared to judge it by a higher moral and spiritual standard. That, in itself, complicates the modern caricature of the so-called “dark” Middle Ages.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

At first it savors trivial goods; these would

beguile the soul, and it runs after them,

unless there’s guide or rein to rule its love.Therefore, one needed law to serve as curb;

a ruler, too, was needed, one who could

discern at least the tower of the true city.~ 91-96 lines

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on the Purgatorio 342

Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory 192

Singleton 346

Sayers 192-93

Purgatorio xiv.91-123

Singleton 349

Sayers 193

Sayers 193

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica II.II, q 95 a 5

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica I.II, q 17 a 1-2

To give this a modern reference, I cannot help but think of the lyrics to a Mumford & Sons song: So tame my flesh / and fix my eyes / a tethered mind / freed from the lies. (I Will Wait, from the album Babel)

Singleton 358

Singleton 356

Singleton 363

Purgatorio vi.88-90

Singleton 364

Singleton 368

Sayers, Inferno 25

Reminds me of Aldous Huxley’s brilliant novel The Island