What We Attend to, We Become: Is Love Beyond Our Control?

(Purgatorio, Canto XVIII): Zeno, Slothful and the "return" of Francesca da Rimini

“I transformed my musings into dream”

~ Dante, Purgatorio XVIII, last line.

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Eighteenth Canto of the Purgatorio, Dante and Virgil meet the Slothful. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

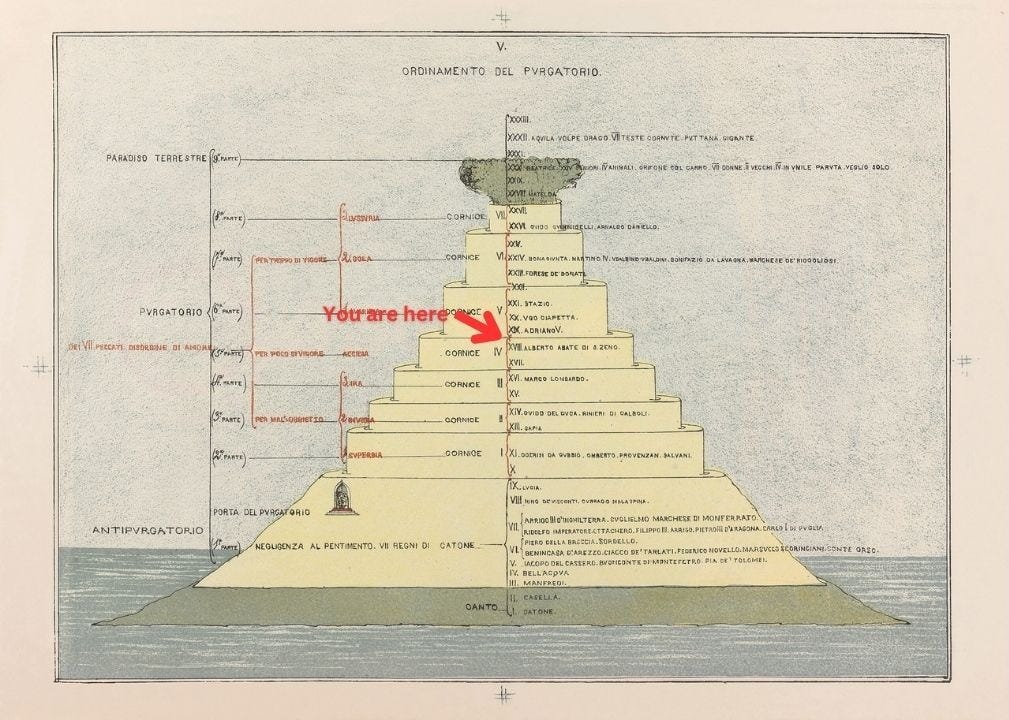

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

The fourth terrace of Sloth - Virgil continues his discourse on love - Dante’s tiredness - The rushing souls of the Slothful - The virtue of Zeal - Mary and Julius Caesar - Abbott of San Zeno - Exempla of Sloth - Hebrews and the Red Sea - Followers of Aeneas.

Canto XVIII Summary:

Virgil’s speech on love, in a pause, had left Dante “goaded by new thirst” (4). As much as it had revealed and instructed, it was not enough to satisfy his curiosity about the nature of love, which had been simplified to its first principle in his understanding of it:

Therefore, I pray you, gentle father dear,

to teach me what love is: you have reduced

to love both each good and its opposite.

xviii.13-15

Virgil continued his discourse, pointing out an even deeper understanding of love than he had before; up until now was just the prelude.

He said: “Direct your intellect’s sharp eyes

toward me, and let the error of the blind

who’d serve as guides be evident to you.”

xviii.16-18

Being of the nature of love, the soul gravitates toward that which its love resonates with; this is the natural love of the first part of the speech in canto xvii.

The origin of love is our instinctive attraction to what pleases us; an attraction in itself natural and blameless.1

The perception creates and draws to itself an image of the thing loved, and meditates upon it, turns toward it. This focused attention moves toward the thing loved. In this conception, the image must be directed at something outside of oneself; this idea of the external object is further explored in the next canto.

Your apprehension draws an image from

a real object and expands upon

that object until soul has turned toward it;

and if, so turned, the soul tends steadfastly,

then that propensity is love-it’s nature

that joins the soul in you, anew, through beauty.

xviii.22-27

This steadfast tending is the first of three elements in the operation of love in the thought of Thomas Aquinas, who drew his theory from interpreting Aristotle’s de Anima; this is the conception that populates Dante’s philosophy.

The image of the upward moving flame seeking to reunite with its own element as an example is also the first of another three conceptions; those of natural love. The soul, embodied, makes its quest just as that flame toward reuniting with its natural element, in this case, toward the thing that pleases. This quest is the second element of love, desiderium; the final stage, in line 33, is the enjoyment of that love once obtained.

Then, just as flames ascend because the form

of fire was fashioned to fly upward, toward

the stuff of its own sphere, where it lasts longest,

so does the soul, when seized, move into longing,

a motion of the spirit, never resting

till the beloved thing has made it joyous.

xviii.28-33

Medieval philosophers for the most part followed Aristotle in supposing that fire mounted, earthy bodies sank, etc., because each element tended towards its “natural place,” where it was most at home; in the case of fire toward the “sphere of fire,” believed to surround the earth between the sphere of air and the sphere of the moon.2

Virgil used this moment to point out that those who “would insist / that every love is, in itself, praiseworthy” (35-36) are in error; he is specifically referencing the Epicureans, whose philosophy, in the most basic sense, emphasized moving toward ataraxia, or tranquility, through the cultivation of pleasure and the avoidance of pain, which some mistakenly thought of as chasing after pleasure in a hedonistic sense.

To complete this thought, Virgil used the metaphor of the wax and stamp; while the love, the intention—the wax—may be good, the effect of the thing loved—the impression—could be faulty, if the object of love is faulty.

Love is a passion, and the lover is one who undergoes an effect originating with some “esser verace,” [true being] an object which stamps his mind, as the image of the seal and wax has suggested. This is true of both natural and elective love: the circle of love begins outside the mind, with the object.3

This discussion had brought up more questions in Dante’s mind as he fine tuned his understanding between determinism and free will; he asked the question that was central to this discourse on love, as well as being the defining question presented by the entire Divine Comedy: if “all movements of the soul are to be seen as movements of love,”4 then how can any movement of love, natural or rational, be bad?

Yet the explanations given by reason and philosophy, through Virgil, were about to reach their limit when it came to answering Dante’s question in full. Virgil knew that only Beatrice, as the voice of theology, would be able to fulfill this question; he called it “truth of faith” (47).

Every substantial form, at once distinct

from matter and conjoined to it, ingathers

the force that is distinctively its own,

A force unknown to us until it acts-

it’s never shown except in its effect,

just as green boughs display the life in plants.

And thus man does not know the source of his

intelligence of primal notions and

his tending toward desire’s primal objects.

xviii.49-57

The soul and body are inextricably linked together, and by that union have the discursive intellect as their unique power; the combination of intellect and will. This is manifested through its expression of itself, just as the green leaves of a plant express it’s life. The plant, like the fire of line 28, becomes the second example of natural love. When Virgil said that humanity cannot know the source of these parts of themselves as they are so innate within us, he compared it to the inborn zeal of the bee for making honey; the primal will acts without guile and so can be neither praised nor blamed.

It should be noted that Dante, in three similes, has drawn on fire (inanimate nature), plants (animate nature), and now bees (sentient nature), following a progression from lower to higher orders.5

And, at the pinnacle of his argument, and the final element that can be explained through reason, Virgil said:

Now, that all other longings may conform

to this first will, there is in you, inborn,

the power that counsels, keeper of the threshold

of your assent: this is the principle

on which your merit may be judged, for it

garners and winnows good and evil longing.

xviii.61-66

That threshold of consent, the keeper of the threshold, is the conscious action of free will.

Free will, now termed an innate virtue, is the power of choice as to means and involves both the apprehensive power and the will. Thus here we have a correspondence and proportion between the perception of the first principles and discursive reason, on the one hand, and the will of the end (natural appetite) and the elective power known as free will, on the other.6

The philosophers of the past, such as Plato and Aristotle, explained the notion of free will, of this “inborn freedom” (68), as ethical philosophy. Beatrice will speak on free will to Dante later, and Virgil encouraged Dante to remember this discourse.7

Wherefore be it known that the first principle of our freedom is freedom of choice…when we see this we may further understand that this freedom, or this principle of all our freedom, is the greatest gift conferred by God on human nature.

Dante, De Monarchia I.xii 2, 6

Each and every love may be awakened in us of necessity, but it lies within our power to check it at the first stage of love, and before the inclination and complacency in the object which is properly so termed becomes a desire and moves toward possession of the object, thus crossing the “threshold of assent.”8

Laborare est orare - To work is to pray

As the moon shone near midnight and Virgil had finished his discourse, freeing Dante from doubt, a sleepy weariness came over him. This, however, was quickly interrupted by the introduction of the souls on the fourth terrace, those of the Slothful, in a frenzied rush of running.

Just as-of old-Ismenus and Asopus,

at night, along their banks, saw crowds and clamor

whenever Thebans had to summon Bacchus,

such was the arching crowd that curved around

that circle, driven on, as I made out,

by righteous will as well as by just love.

xviii.91-96

The rivers Ismenus and Asopus, in the region of Boeotia, were near Bacchus’ birthplace, and the frenzied and orgiastic gatherings of the gods’ followers would converge along their banks. The running shades, unable to stop in their Zeal, called out the examples of that Zeal, their Whip, or examples of the virtue of that terrace. They called them out quickly as they ran:

In her journey, Mary

made haste to reach the mountain, and, in order

to conquer Lérida, first Caesar thrust

against Marseilles, and then to Spain he rushed”

xviii.99-102

Mary, upon receiving a message from an Angel about the pregnancy of her cousin Elizabth (who would become the mother of John the Baptist) hurried to see her:

And Mary arose in those days, and went into the hill country with haste, into a city of Juda; and entered into the house of Zacharias, and saluted Elisabeth.

Luke 1:39-40

Julius Caesar, as he traveled to Spain to fight, attacked Marseilles on the way, and then went on with haste to battle at Lérida before continuing on to battle with Pompey in Spain; describing the energy with which Caesar moved forward into battle, Lucan said:

Just so flashes out the thunderbolt shot forth by the winds through clouds,

Accompanied by the crashing of the heavens and sound of shattered ether;

It split the sky and terrifies the panicked

People, searing eyes with slanting flame.

Lucan, Pharsalia I.151-154

The rest of the rushing souls continued on, calling out their haste, “lest time be lost through insufficient love” (104); one called out as he ran, pointing Virgil and Dante to the passage upward. That soul was Gherardo II, abbot of the church of San Zeno during the time of the Emperor Frederick I. As Gherardo rushed away, Dante and Virgil were quickly left far behind.

Yet just as the whips to Zeal were said in haste and in passing, so were the examples of the bridles, those who exemplified the error of this terrace, called out. Two running souls named the Hebrews in their journey in the desert, as well as the crewmates of Aeneas on their journey to Italy from Troy, who were tired of the journey and stayed behind in Sicily, as the examples of Sloth.

The Israelites were sluggish and recalcitrant in crossing the desert after the Lord had caused the waters of the Red Sea to divide so that they marched across it as on dry land, while the Egyptians perished in it. Joshua and Caleb were the two exceptions; aside from them, only those Israelites who had been born in the desert reached the Promised Land.9

The reference is to those of Aeneas’ band who chose to remain in Sicily with Acestes and so avoid the hardship of the journey: Weary are they of bearing the ocean-toil.10

With the discourse finished and the souls having run away, Dante was left to meditate on the many thoughts that presented themselves to his mind, and with this, he fell into dreams.

💭 Philosophical Exercises

The metaphor of a torch in the dark forest from the previous canto helped us understand the nature of attention, or, as Dante describes it, Love, and how it directs its gaze.

So, for the sake of simplicity, I will use the terms Love and Attention interchangeably, for both suggest a kind of magnetic force, something that draws objects nearer to us, pulling them into the orbit of our concern.

Unlike a physical magnet however, Love and Attention don’t simply attract opposites. Their pull is subtler, and much more mysterious. But let’s explore this further.

Let us explore this by stretching our imagination once more. Imagine this, my dear reader: you and I stand together at the edge of a high cliff, the wind pressing gently against us, and we are about to leap into deeper waters below.

I. Islands: The Island of Apprehensiva

We have finally, after both hesitating for a while, leapt from the cliff’s edge together and plunged into the deep waters. The first island we have to swim towards is the island of apprehensiva for it is here, according to Aristotelian, Thomist, and Augustinian thought, that the soul first perceives the images of the external world.

This island that we reach, after conquering the frosty waters, is rich with forms, filled with images similar to those we have encountered on the terraces so far, drawn from ancient and biblical stories, each offering a model for how to imitate virtue and the good. But this island is not decorated only with beauty. There are also images that disturb, that caution us, that show us what we must learn to resist.

These images enter the soul. They become part of us.

If I may ask my reader: please look around yourself on this island, what images do you see, which ones flow into your mind? They can be either some images that comes to your apprehensiva from The Divine Comedy or from your own daily life.

Have you captured that image?

If yes, let’s swim to the next island.

II. Island of Imaginativa or Fantasia

Immediately upon reaching the shore of this second island (even before our clothes have had time to shed the last drops of water) we find ourselves once again drenched, this time in thought.

There, on the shoreline, we see contemplation.

You and I see people, much like us, ruminating, reflecting on the images they gathered from the first island. They are sorting, discerning, turning each one over in their minds like a seashell in their hands, asking which images are worthy to be kept, and which must be let go.

This is one of the processes of our soul: we first gather images, then they get imprinted onto our souls like images get imprinted on wax.

This is why, on the far shore of this second island - the island of contemplation - we no longer see our fellow travellers merely contemplating images, they are now imprinting them onto wax.

The representations we gather, as I mentioned before, can be of virtue or vice. And the kinds of images we imprint depend entirely on what we choose to attend to. The more frequently you return to a particular image, the more deeply it sinks into the wax of the soul.

In fact, this is one of the core principles behind how propaganda works. The mind may resist new information the first time it appears. But by the second or third exposure, it begins to feel familiar. It no longer registers as something new or worthy of scrutiny and so it slips past the gates of critical thought.

But that, of course, is a story for another time.

III. Meeting Dante

Before we swim, or perhaps sail, to the next island, my reader and I will meet Dante. He will be standing on the shore, waiting for us.

He will tell us whether we are permitted to continue by swimming or by boat - for each method leads to a different island. The path we take will depend not on chance, but on the images we chose to carry with us.

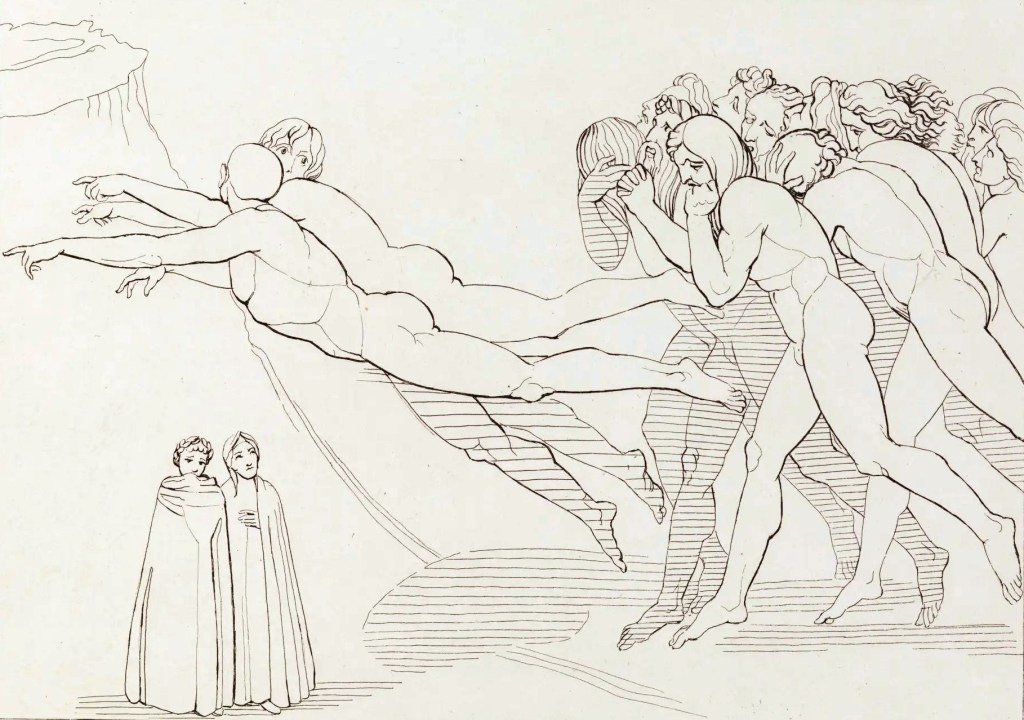

Does my reader remember Francesca da Rimini?

We met her in the Inferno, among the souls of the lustful. There, Francesca described Love as an uncontrollable force, something that seizes us and drives us beyond our will, stripping us of control.

But Dante’s own view of Love is far richer, far more nuanced. For him, Love is not simply a storm we are caught in, it is the very energy that drives the soul. And crucially, it can be guided.

We can take hold of this force by learning to control the images we allow into our minds. The things we attend to, contemplate, and return to with our gaze - they draw us toward certain inclinations, forming the shape of our desires.

Let us not forget: Francesca and Paolo began by reading romantic tales together, stories filled with images of passion and forbidden longing. They didn’t fall immediately. First, they read. Then they reflected. Then they succumbed.

This is the quiet power of attention. What we dwell upon, dwells in us.

So, when we reach Dante, he will ask us a simple but piercing question: Is the image you hold in your hands, the one imprinted on the wax of your soul, truly the one you wish to attend to?

For if we say yes, that very act sets something in motion. It stirs desire. It awakens a pull within the soul: drawing us, slowly but surely, toward the object we have chosen to contemplate.

IV. Our mind is shaped by what it repeatedly attends to

For Francesca, love was deterministic by its nature. In her words, she had no choice but to succumb to it, but for Dante the choices we make, the images we select, the fantasias we choose to attend to, determine in itself and act of free will.

Love is not a raw feeling but the directed inclination of the soul toward something it has chosen to attend to. Love in its very self is not blameworthy, but what we love, how much we love and whether we choose to restrain or cultivate that love - that is where the moral weight lies.

Every day we choose whether we should build our day around prayer or around appetite; around stillness or overstimulation; around beauty or mediocrity. The ocean is nothing but a collection of tiny drops, the desert is nothing but a grain of sand, a house is nothing but a collection of individually insignificant bricks layered harmoniously together.

And this is where we come back to Dante at the shore telling us whether we are going to reach the next destination by boat or by swimming. The truth is that there is no next destination for those who choose vice over virtue.

Vice is not a violation of a religious dogma, but a stab that wounds your own life. If your ego hinders your own progress it is you who suffers. If you refuse to forgive, it isn’t the person who hurt you who suffers, but you who carries the weight of the chain. When you wear a mask for too long, you forget the shape of your own face.

Vice is like a water drop that evaporates and never becomes part of the ocean. It is a grain of sand that vanishes into the grass and can no longer dream of becoming a powerful sandstorm; vice is a single brick of stone which on its own can never dream of becoming a house or part of a beautiful cathedral.

So, if the image we present to Dante is one of vice, he will send us into the waters to swim, aimlessly, without destination, until, eventually, we drown. But if we offer him a virtuous image, he will place in our hands a boat and a compass. For when one chooses a noble pursuit, one also chooses a guiding star.

This is the very nature of Dantean free will. The Divine created the beautiful landscapes that surround us, but it is we who must attend to our own gardens.

(There are more Philosophical Exercises in the next section)

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

I. Mere “Study” Without Action is Fruitless

Every other terrace in Purgatorio includes a prayer—except the terrace of sloth. As the commentator Carroll (1904) observes:

“It is only when ‘study’ is accompanied by action that it makes ‘grace bud again.’”

This unity between prayer and action, between study and action, continues to fascinate me.

It is foolish to act without first studying or praying - this is how mistakes are born. But equally, if we only study and never act, we fall into inertia. We risk drowning in sloth, where knowledge becomes stagnant and grace cannot grow.

This is why the slothful of this terrace are running with tremendous zeal, zeal they never had while alive.

II. Mary and Caesar

Sloth is the insufficiency of Love.

Earlier, we explored Love as a driving force: an energy that propels the soul into action. Just as bees are drawn to flowers to extract nectar and make honey, Love moves us toward our proper tasks. To be slothful means not that one refuses to act, but that one does not love enough what must be done.

If you’re wondering how to ignite this fire of Love, return to the Philosophical Exercises of the previous and present cantos. The first step is to direct our attention toward the right object of Love. The second is to imprint the right images on the wax of the soul, images that nourish action rather than drain it.

In this canto, Dante offers us two powerful counter-examples to sloth.

The first is Mary, who rushes to Elizabeth after learning that she is pregnant. Despite being pregnant herself, Mary does not hesitate. Her Love for Elizabeth overrides any inclination to remain still. Her movement is a testament to the zeal and vitality that true Love inspires.

The second example comes from ancient Rome: Julius Caesar, during his campaign in Spain. His swift and decisive action reveals not just military ambition, but a form of focused intensity that Dante interprets as a virtuous zeal, a worldly echo of the urgency Love demands.

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

The last lines of this canto perfectly describe my current state of mind.

Then, when those shades were so far off from us

that seeing them became impossible,

a new thought rose inside of me and, fromthat thought, still others—many and diverse—

were born: I was so drawn from random thought

to thought that, wandering in mind, I shutmy eyes, transforming thought on thought to dream.

Dorothy L. Sayers, Purgatory 210

Sayers 141, 210

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on Purgatorio 421

Singleton 422-423

Singleton 429

Singleton 431

Paradiso V.19-24

Singleton 437

Singleton 445-446

Singleton 446

Beautiful. Clarifying. Inspiring. Thank you.

"For when one chooses a noble pursuit, one also chooses a guiding star.

This is the very nature of Dantean free will. The Divine created the beautiful landscapes that surround us, but it is we who must attend to our own gardens."

When you said our attention draws the object towards us, I thought also of how people are literally and almost physically drawn into their social media devices. With encapsulating virtual reality devices they may as well be. With that their attention will be completely ensnared. Virtually imprisoned. Imprisoned virtue?