You Cannot Know Your Fate: The Deception of Seers and Sorcerers

(Inferno, Canto XX): Seers, sorcerers and astrologers

The gods perceive what lies in the future, and mortals, what occurs in the present, but wise men apprehend what is imminent.

~ Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! 🌒

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

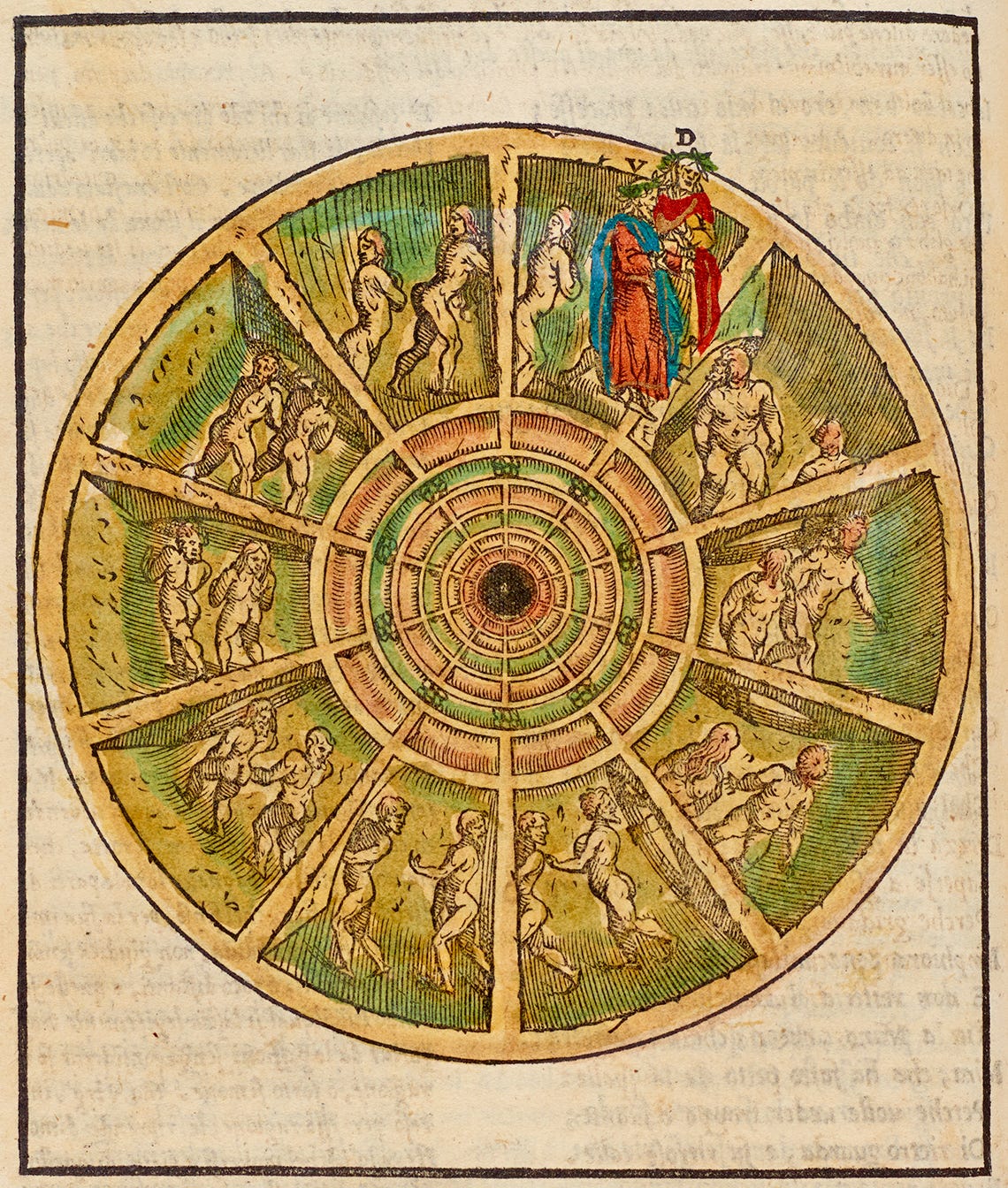

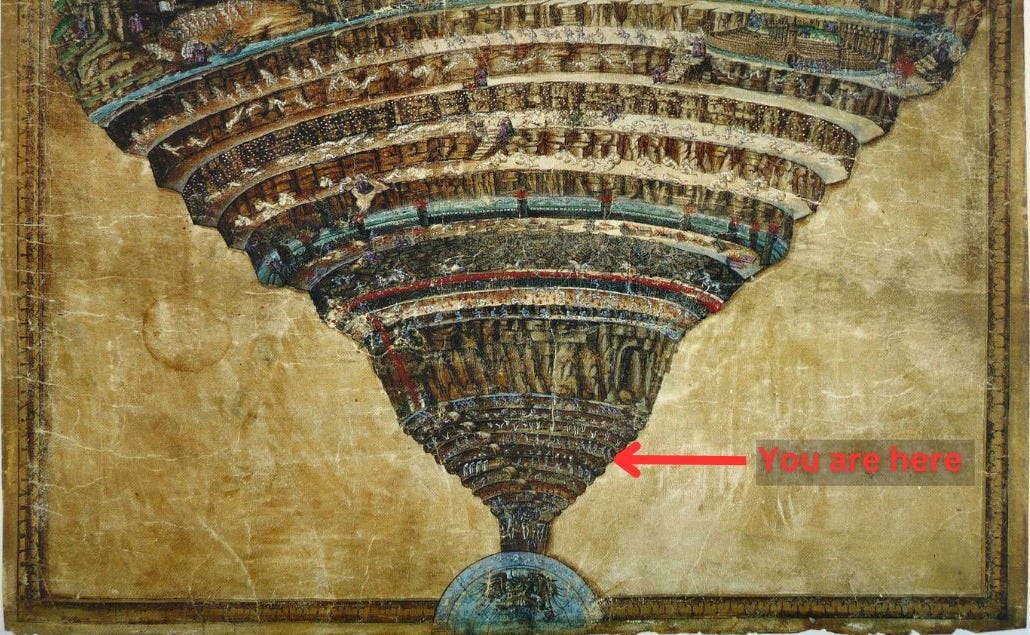

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Twentieth Canto we enter the fourth pouch of the Eighth Circle and the Sorcerers and Astrologers. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

Circle Eight, Fourth Pouch - Sorcerers, Magicians, Astrologers - Their heads and necks twisted - The sinners can only walk backwards - Amphiaraus, Tiresias and Manto - Virgil recounts the founding of his home city of Mantua.

Canto XX: Summary

Dante calls out in the opening of Canto XX that he is looking to a new group of sinners and a new punishment that is in need of exploration. The first canticle is the Inferno itself, the first “song” of the three songs of Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. They have arrived at the fourth pouch of the Eighth Circle.

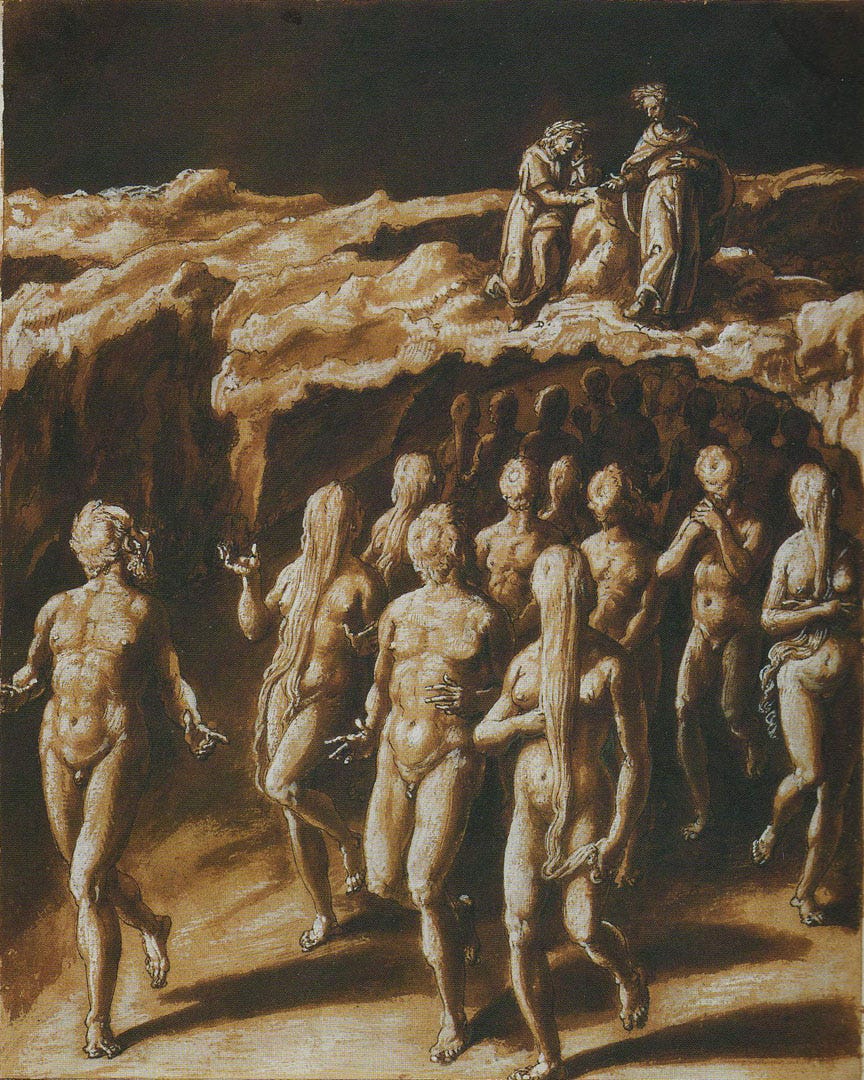

He could see down into the trench, the floor of it wet with the tears of suffering. The sinners walked quietly, sadly, and slowly. Their bodies confessed their punishment; their heads twisted backward, looking forever behind, even walking backwards, the twisting an impediment to all their movements (13). He had never seen anyone in the world above, who, even suffering the most extreme paralysis, came close to being as twisted as these souls. The figure he sees has tears streaming down its back and buttocks; Dante wept with pity, (XX.23-25) but Virgil, seeing Dante weeping and leaning on the rocks, rebukes his foolishness:

Here pity only lives when it is dead:

for who can be more impious than he

who links God’s judgment to passivity?

XX.28-30

Here are the same lines from the Musa translation:

In this place piety lives when pity is dead

for who could be more wicked than that man

who tries to bend divine will to his own!

XX.28-30

This bending of the divine will to one’s own is the hallmark of sorcerers, seers, magicians, and the like, the inhabitants of this fourth pouch; their “twisted sight looks to self instead of to God for the source and direction of [their] power.”1

Virgil points out the first of the sinners in this fourth pouch: Amphiaraus (31-39), a seer who was one of the Seven against Thebes in Greek myth.2

You see how he has made his back his chest:

because he wished to see too far ahead,

he sees behind and walks a backward track

XX.37-39

Next they see Tiresias (40-45), whose story is found in Ovid. Tiresias, having been both a man and a woman, could answer a dispute between Juno and Jove. He answered in favor of Jove, upon which Juno struck him blind. Jove gave him the gift of prophecy - vision - to replace what Juno had taken away. Aruns (46-51) was an Etruscan diviner in the northwest of Italy who foretold the Roman civil war. He lived in the Luni hills, known for mines of exquisite marble.

Virgil begins the story of the founding of his home city, Mantua, with the figure of Manto (52-99). Regarding Manto’s “disheveled locks” the commentator Benvenuto says “here [Dante] hints at the witches who sometimes go about at night, naked, with their hair loose.”3

In Dante’s version of Virgil’s speech, Manto was a prophetess, and the daughter of Tiresias. She fled Thebes and the tyrant Creon, and after wandering for years founded Mantua, the city in which Virgil was born. Virgil describes it’s placement and geography (61-81); Manto traveled from beautiful high and savage landscapes - where the bishopric of three district met on an island in lake Benaco, and where they could all say mass if they were there together because of this meeting of districts (67-69) - and follows its course until it spreads out from its mountain paths into flat, even stagnating plains:

And when she passed that way, the savage virgin

saw land along the middle of the swamp,

untilled and stripped of its inhabitants.

And there, to flee all human intercourse,

she halted with her slaves to ply her arts;

and there she lived, there left her empty body.

XX.82-87

There is more on the story of Manto below in the Philosophical Exercises.

Dante asks if there is anyone in that trench of note that he should speak to, and Virgil points him to Eurypylus (106-114). Virgil sung of him in the Aeneid as an augur, a priest who could read the signs and omens of religious significance.

Virgil points out others being punished in this fourth pouch: Michael Scot who “knew how the game of magic fraud was played” (117). He was a court astrologer, a philosopher, and translated works from Arabic into Latin. Guido Bonatti was an astrologer and diviner from Forli who advised on political matters using his special foresight. He wrote a treatise on astrology and worked for a time as advisor to Frederick II.

Asdente, a shoemaker “who now would wish he had attended to / his cord and leather, but repents too late” (119-120), was said to have magic powers. Finally, they saw the sad, unnamed women who “ had left their needle, / shuttle, and spindle to become diviners; / they cast their spells with herbs and effigies” (XX.121-122). Their herbs and magic potions went along with the waxen effigies used in magical rituals, to control the will of others.

Virgil points out the signs of the approaching morning by the stars - “Cain with his thorns” (124) - their man in the moon - indicates it is time to keep moving.

They continued on.

💭 Philosophical Exercises:

Don’t run ahead of God

~ a Russian proverb

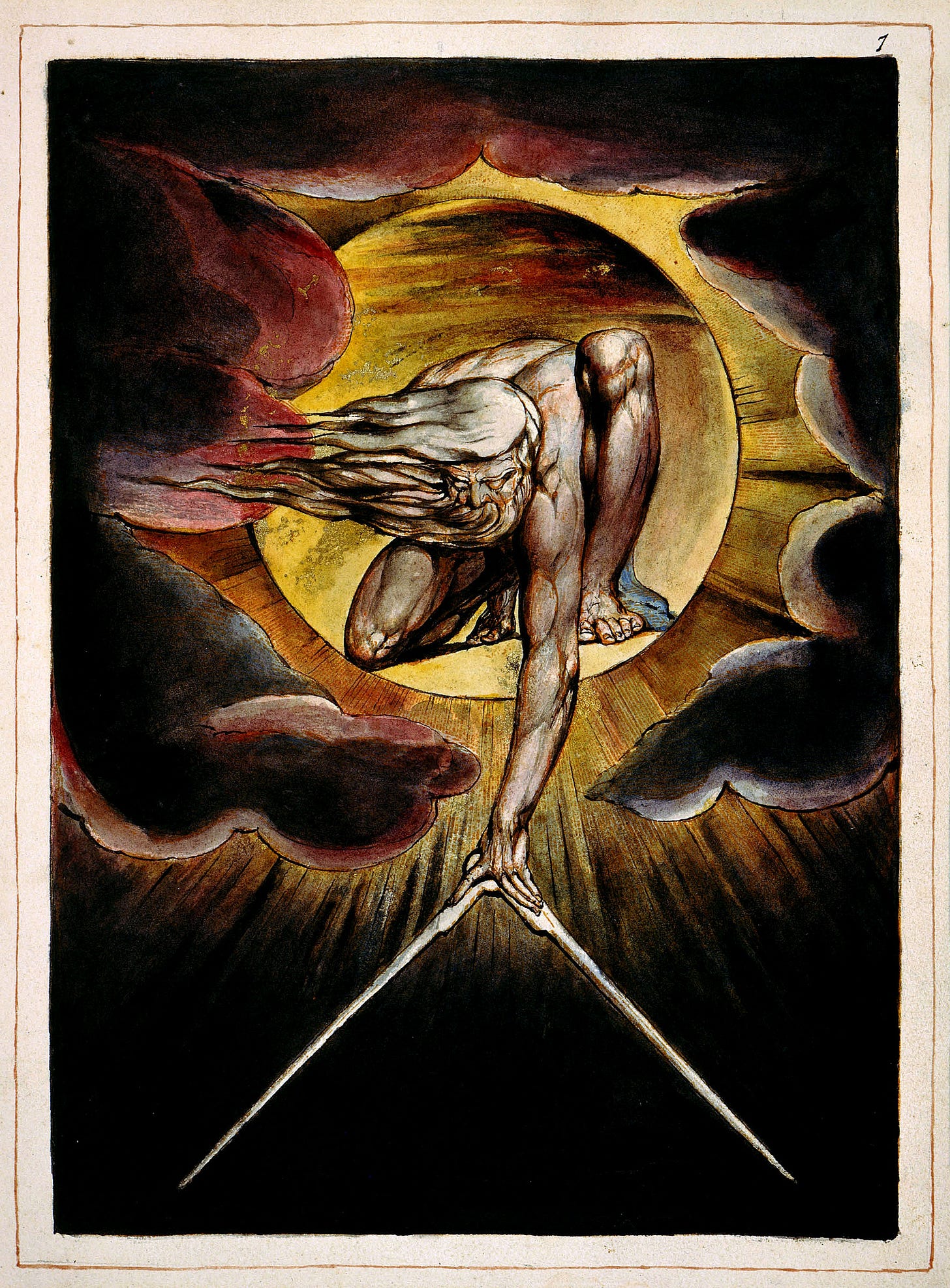

I have placed this William Blake painting on the wall of every reading nook and library I’ve ever had. It portrays Urizen, a god traditionally associated with the geometric and mathematical harmony of the universe. However, that is not the reason I chose to frame this painting and place it where I can see it as often as possible.

For Blake, Urizen was a cold and restrictive god; it represented calculating reason, which imposed its rigid laws upon the world, thus impeding imagination.

At first glance, prophecies, seers, and divinations may seem unrelated to this cold-hearted god. However, Blake, an admirer of Dante, created numerous illustrations for The Divine Comedy. If we observe the damned in this bolgia—those whose necks are twisted backward—we begin to see a connection. Let us start with Amphiaraus.

‘Amphiaraus was one of the seven kings who joined in the expedition against Thebes; foreseeing that the issue would be fatal to himself, he concealed himself to avoid going to war, but his hiding place was revealed by his wife Eriphyle…’4

Amphiaraus meets his end in battle when the earth swallows him—his wife and son perishing as well for their betrayal. Yet one might wonder: why is he being punished if all he did was attempt to evade death? Would we not all do the same?

Some commentators suggest that Dante places him here because Amphiaraus tried to “escape his destiny.” But this interpretation seems inconsistent, for in the Canto of Suicides, Dante explicitly asserts the primacy of free will. To condemn Amphiaraus for resisting fate would run contrary to Dante’s broader Christian vision, where moral responsibility is tied not to fate but to choice.

Amphiaraus is damned not because he knew his fate for certain, but because he self-prophesied his death; this links up to another thinker whom Dante admired and whom we met in Limbo, and that is Seneca.

See how he’s made a chest out of his shoulders;

and since he wanted so to see ahead,

he looks behind and walks a backward path.(Inferno XX, lines 37-39)

Seneca wrote that we suffer more in imagination that we do in reality. When our mind rushes ahead of itself, tries to predict the future, to forecast and foretell what hasn’t yet happened, we lose control of ourselves. When we act as our own seers, predicting an outcome with certainty, we unconsciously align our actions to fulfil that very prophecy. In doing so, we summon the doom we foresaw—not as an inevitability, but as something that could have been avoided had we not called it upon ourselves.

Like Urizen, who confines the boundless possibilities of the universe within his rigid, calculated vision, so too do the seers. They reduce the fluid uncertainty of the future to the narrow certainty of their own prophecy.

This is precisely the story of Amphiaraus, but what about Tiresias?

If Amphiaraus represents self-prophecy, Tiresias rises from individual to social seership, foretelling the future that affects entire societies and nations.

Once again, one can write an entire book on Tiresias’ symbolism, the story of him striking two mating serpents and being transformed into a woman for seven years is deep and rich with symbolism in itself.

In Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, Tiresias is the seer to whom King Oedipus turns to uncover the cause of the city’s afflictions. He is told that the plague gripping Thebes stems from the unresolved murder of King Laius and that Tiresias alone can reveal the culprit. At first, the prophet resists, knowing the devastation his words will bring. But when pressed, he gives up, delivering the prophecy that will seal Oedipus’ fate—the murderer he seeks is none other than himself.

But of course the most mind-blowing twist, a spectacular battle between Dante and his guide unfolds secretly right in front of our eyes. Virgil tells us a story of how his native city of Mantua was founded and the story he tells to Dante differs radically from the account he offers in his poem the Aeneid. In the Aeneid, Mantua was founded by Ocnus, the son of seeress Manto.

In this canto, however, Dante, who knew the Aeneid by heart, forces his guide to tell a different version of the story—one where Mantua was founded by Manto herself. According to Dante, the city arose not from the lineage of Ocnus, as Virgil wrote, but as a tribute to the prophetess, built upon the very ground where people once gathered to seek her visions.

There is a close-knit connection between the foundation myths of ancient cities—Troy, Mantua, Rome, Florence—all of which were built upon legends, and Dante perceives a danger in this. If Amphiaraus embodies self-prophecy and Tiresias represents societal prophecy, then Manto personifies foundational prophecies—the myths upon which entire civilizations rest.

It is worth noting that all the seers Dante condemns in this bolgia hail from the pre-Christian classical era. It is as if Dante is underscoring that Amphiaraus could not have known his future because he lived before the Christian truth was revealed, before divine providence replaced the uncertainty of pagan fate.

Final Thoughts on Sorcery

We have covered much in this part of Philosophical Exercises and yet have only grazed the surface of Dante’s vision. I had to leave out certain figures, such as Aruns—who, I believe, represents event-prophecy, as the Romans once sought him to divine the outcomes of great conflicts, including the civil war between Caesar and Pompey.

Two ideas in this canto have left me sleepless at times, reshaping my philosophy of life. The first concerns free will; the second touches upon Stoicism—or, more broadly, ancient practical philosophy.

In the Christian worldview, we, as creations of God, are endowed with free will—the capacity to choose and to shape the course of our lives. Only the all-knowing God possesses foreknowledge of the future. Thus, anyone who claims the power of prophecy either denies human agency, asserting that our choices are predetermined5, or elevates themselves to the level of divine omniscience—an act of hubris that, in Dante’s moral universe, invites its own punishment.

The second idea can be described in connection with William Blake’s deity called Urizen. Amphiaraus, for example, died before he actually reached the battlefield. He died in his mind, because he suffered in his imagination more he did in reality. The universe is too complex for us humans to be able to predict the infinite ways the events might unfold. Anyone who claims to know his fate, let alone the fate of someone else acts like Urizen, who cold-heartedly reduced the majesty of the universe to rigid self-invented laws.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Argument Against Dante? But Wise Men Know What is Imminent

(Difference between Wisdom and Prophecy)

The Greek poet C.P. Cavafy has a line in his poem where he says:

Mortal men perceive things as they happen.

What lies in the future the gods perceive,

full and sole possessors of all enlightenment.

Of all the future holds, wise men apprehend

what is imminent.

‘…wise men apprehend what is imminent’. We can still foresee the course of our lives without turning to seers, prophets, or astrologers. The wise discern what is imminent not through divination, but through careful observation—of how individuals shape their daily existence and in what sort of values a particular society has.

There is no secret that a person addicted to particular substances will meet a certain imminent end if they won’t change their life. We are what we repeatedly do after all. In the same way one can foresee that greed destroys the fabric of society, and a society that refuses to replace vice with virtue will imminently collapse.

This means that our actions have consequences. The problem of those who consult seers is that they switch responsibility from themselves onto the future.

Popularity of Dark Arts

Interestingly, astrology was a subject of interest to Dante. It is worth noting that, to some extent, astrology served as a precursor to astronomy. As modern physicist Carlo Rovelli highlights in his essay on Dante, the great poet envisioned a three-sphere structure of the universe centuries before Einstein provided scientific evidence for it.

Dante Addressing Us

May God so let you, reader, gather fruit

from what you read; and now think for yourself

how I could ever keep my own face dry

I recall Dante urging us to pay close attention when we stood outside the gates of Dis. There, we had to sharpen our focus to grasp the nature of despair and the sinners we would soon encounter in the Lower Hell. It is as if Dante is telling us that the Furies embody one aspect of despair, while the seers—such as Amphiaraus—are not merely figures from the pagan past but also represent a particular kind of prophecy.

Dante tells us that the fruit is there, right in front of our eyes, if we dare to notice it, then pluck and eat it.

Isn’t this always like this with knowledge?

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

Mortal men perceive things as they happen.

What lies in the future the gods perceive,

full and sole possessors of all enlightenment.

Of all the future holds, wise men apprehend

what is imminent. Their hearing,

sometimes, in moments of complete

absorption in their studies, is disturbed. The secret call

of events that are about to happen reaches them.

And they listen to it reverently. While in the street

outside, the people hear nothing at all.~ C.P. Cavafy, But Wise Men Apprehend What Is Imminent

Characters:

- Amphiaraus - One of the kings of the Seven Against Thebes, Amphiaraus foresaw that he would die during the siege on Thebes so he attempted to hide, but his wife Eriphyle gave his position away. As he fled from Polynices, an earthquake shook the land and he was killed by being swallowed up in it; Statius gives a vivid retelling in his Thebaid:

Troops stand back,

As all suspect the ground, giving wide berth

To land so treacherous, and vacant lies

The site of ravenous destruction, shunned

In awe of that infernal sepulchre….

by chance he stood

Nearest the prophet as he fell, poor soul,

And blanched to see the chasm gaping wide…

The impious earth sucks in

Warriors and arms. This soil, look, where we stand,

Seems to be fleeing. I myself beheld

The road to night's dark depths, the solid earth

Riven and he, than whom none dearer to

The prescient stars, the prophet Amphiaraus,

Dropping, and stretched my arms and cried in vain.

A miracle it was: still master of

His steeds he left that fissured smoking place,

The foam-bespattered field.

Statius Thebaid VIII.126-130, 134-136, 141-150

Tiresias - A Theban seer whose story of transformation is found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Juno and Jove were arguing a point, and agreed to ask Tiresias to settle the dispute. Having been both a man and a woman, he was in a unique position to answer their dispute of who enjoyed sex more; Tiresias concluded that it was women.

Both agreed to seek the arbitration

Of Tiresias,

Who, in a leafy forest, had once profaned

The coupling of two enormous serpents,

By giving them a blow with his walking stick.

A wonder, for at once he was transformed

Into a woman and remained as such

For seven years. But when the eighth year came,

He saw the same two serpents once again

And said, “since striking you has the effect

Of turning one into one’s opposite,

I’ll strike you once again.”

And having done so,

Became the image of this former self.

Metamorphoses III.415-426

Aruns - In Lucan’s Pharsalia, there is a sequence of events in which Aruns, the seer, or auger, sacrifices a bull and reads the signs of it’s death and sacrifice to foresee the Civil War between Pompey and Julius Caesar. The bull fought against them in being led to sacrifice, and the state of it’s body and organs did not bode well for the turmoil ahead.

When from these signs he understood the prophecy of great disaster,

he exclaims: 'It is hardly right for me, gods, to reveal to the peoples

all the turmoil which you plan; and, greatest Jupiter, I have not appeased

you with this offering, but infernal gods have come into

the slain bull's breast. Unutterable are the things we fear, but soon

our fears will be exceeded.

Pharsalia I.630-635

- Manto - The prophetess after which Virgil’s hometown was named.

- Eurypylus - An augur, or priest skilled in reading the signs of prophecy. In Dante’s version of the myth, Eurypylus and Calchas “cut the cables’ of the ships of Greece heading to Troy in their method of gaining a favorable wind after weeks of waiting, stagnant, to set sail toward battle. Calchas called for the sacrifice Agamemnon’s daughter Iphegenia in order to get the favorable wind they needed. However, in the Aeneid Eurypylus’ only role is in consulting the oracle of Apollo to find out when they should leave Troy:

Baffled, we sent Eurypylus off to find answers at Phoebus’

Oracle. But his report from the shrine was completely horrendous.

Aeneid II.114-115

Sayers Hell 199

See Inferno XIV.68-69

Singleton 351

Hollander, 372

Christian worldview also has an idea of predetermination in our life, but it is very different from being determined, or from the ancient view of predetermination. Boethius touches upon this perfectly in his book, where he shows us how we can have a free-will and yet have a life that is predetermined. I guess we have to do Boethius read-along in 2026!

Despite the of chiding of his underworld guide Virgil, I continue to be moved by Dante's humanity and compassion in this hellish place. "... now think for yourself how I could ever keep my own face dry when I beheld our image so nearby and so awry that tears, down from the eyes, bathed buttocks, running down the cleft. Of course I wept, leaning against a rock along that rugged ridge" (Mandelbaum XX: 20-26). When the fate of his fellow human beings calls for empathy it's there, as is his sense of righteous justice towards the more serious sinners. The delicate balance between these two states has been captured so well in his words.

"I guess we have to do Boethius read-along in 2026!"

Yes!:)