Dante and Cato: Don't Let Your Dreams Die -Put off the old man, and put on the new

(Purgatorio, Canto II): Music that turns one into stone, Angels and Demons, Casella

“Man is so constituted that he then only excels other things when he knows himself.”

~ Boethius

Welcome to Dante Read-Along! ✨

(If this post appears truncated in your inbox you can read it on the web by clicking here. )

Welcome to Dante Book Club, where you and I descend into Hell and Purgatory to be able to ascend to Paradise. Our guide is the great Roman poet Virgil and in this Second Canto of the Purgatorio, we meet the souls arriving into Purgatory. You can find the main page of the read-along right here, reading schedule here, the list of characters here (coming soon), and the list of chat threads here.

In each post you can find a brief summary of the canto, philosophical exercises that you can draw from it, themes, character, and symbolism explanations.

All the wonderful illustrations are done specially for the Dante Read-Along by the one and only Luana Montebello.

This Week’s Circle ⭕️

The base of Mount Purgatory - The glow of Dawn over the ocean - A fast moving light in the distance - The form of a bright, winged angel - The boat carrying the newly arrived souls - They sing a Psalm of Exodus and deliverance - Casella the musician sings to soothe a weary Dante - They are rebuked by Cato - The souls and the poet and pilgrim scatter, looking for a path up the mountain.

Canto II Summary:

As the sun rises over the waters from Dante and Virgil’s perspective on the shores of Mount Purgatory, Dante places them in space and time through his exposition on the placement of the heavenly bodies in the sky in alignment with specific places on earth.

Purgatory, in the southern hemisphere, is in opposition to Jerusalem, which Dante considered to be the center of the known world in the northern hemisphere. While it is sunset in Jerusalem, it is sunrise in Purgatory and midnight over the Ganges river in India. Noon is the missing element, and we can consider that it is over Cadiz, west of the Straits of Gibraltar, where Ulysses may have left from as he and his crew took their final adventure.1

The Scales of line 5 are those of the constellation Libra, whose “Scales are said to fall from the hand of night when night overcomes the day.”2 Aurora, the goddess of the Dawn, - familiar to readers of Homer’s famous epithet the ‘rosy-fingered dawn’ - was also known as Eos in antiquity:

Eos, who shines upon all men on earth

And on the deathless gods who hold broad heaven.

Hesiod, Theogony 374-375

Now that the dawn of Easter morning has been established, the story continues, with Dante and Virgil standing, contemplative, on the shore, where Virgil has just washed Dante’s face with dew and tied the rush girdle of humility round his waist:

We still were by the sea, like those who think

about the journey they will undertake,

who go in heart but in the body stay.

ii.10-12

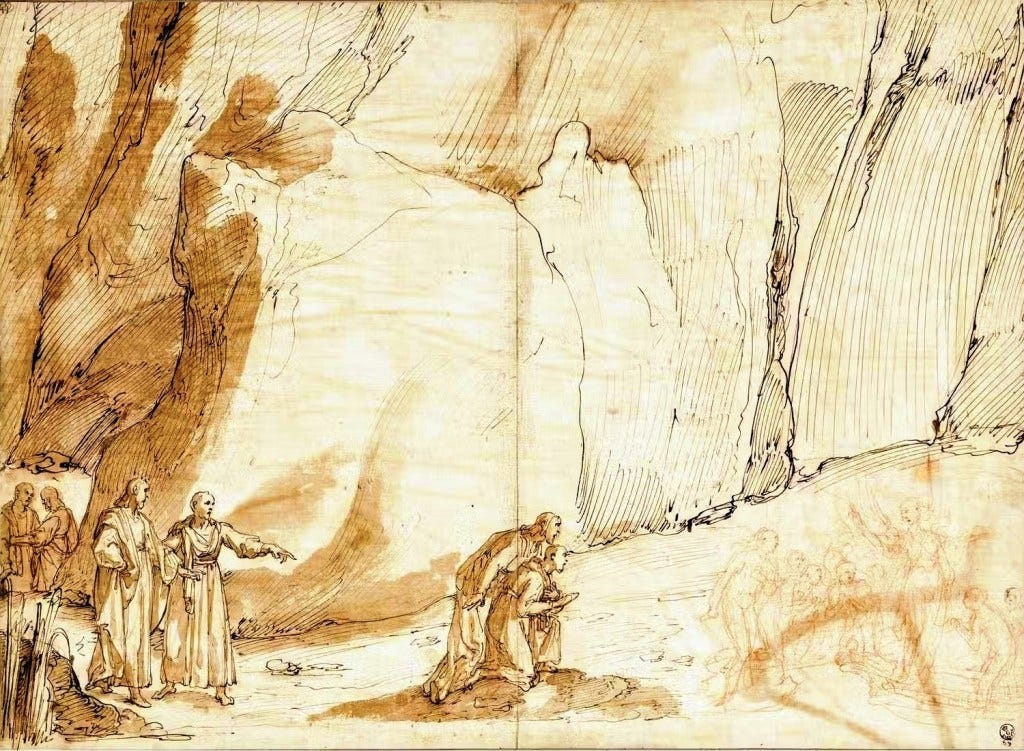

As they stood, Dante saw a swiftly moving glowing light, one that, on reflection, he prays that he will see again. How different is this hopeful vision to the portents of the unknown in the Inferno! As the light moved with incredible speed toward them, it began to manifest into form, with a glowing whiteness on either side and one beneath; as the image became clearer as wings, Virgil recognized it and cried out with an imperative command:

“Bend, bend your knees; behold the angel

of God, and join your hands; from this point on,

this is the kind of minister you’ll meet.

See how much scorn he has for human means;

he’d have no other sail than his own wings

and use no oar between such distant shore.

ii.28-33

The last time that we saw an angel was outside the gates of Dis,3 one full of wrath for those cast out from Heaven. This angel navigates the divine boat with only his wings, “pointing heavenward to the source of the power whereof he is the instrument,”4 piercing the air as he fans them to move the boat with such swiftness. Compare the power of these wings with those bat-like wings of Lucifer, deep in the Inferno, creating not movement, but stagnation and immobilization.

As the boat neared them on the shore, the light of the angel overwhelmed Dante with it’s brightness, so much so that Dante could not bear to look; a theme that we will encounter again and again as we rise through Purgatorio and into Paradiso;5 and to think, that if Virgil had not begun the purification process by washing the stain of Hell off of Dante, he may truly have been blinded.

The boat arrived at shore, gliding along the top of the waters as the souls within held no weight. The “celestial pilot” was of such divinity - that is, so “inscribed” with blessedness - that even the thought of them brought that same blessedness to the one considering him. His ship was full of souls; they are in fellowship, in unison, of one purpose, singing together the first line of the Psalm of the Exodus: - In exitu Israel de Aegypto - “when Israel went forth from Egypt” from Psalm 113.

This passage is worthy of a full exposition on its own, as the first line sung is the example used by Dante in his Letter to Can Grande, his patron, to explain the last of four levels of allegorical interpretation - sometimes called Medieval Exegesis - that he used in crafting his text. The Letter is contained within Dante’s Convivio, and the relevant passage is footnoted below.6

This single verse is supposed to bring the rest of the psalm to mind. The song is appropriate to the time of the journey, since this is Easter Sunday morning, and Exodus signifies, of course, Passover and Easter. Presumably all souls as they reach this shore would sing this psalm, a hymn of thanksgiving for liberation from “Egypt” and the bondage (of sin), as the closing verses of the psalm make clear: “It is not the dead who praise Thee, Lord, nor those who go down into silence; but we bless the Lord, both now and forever.”7

The Exodus of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt to the Promised Land was interpreted in three ways: as prefiguring the Redemption of the human race by Christ; as representing the moral conversion of Christians from sin to grace during their lives; and as foreshadowing the final journey of the souls of the saved, after death, from this world to Heaven. In this journey, the living Dante, following Christ by descending into Hell and rising again, is making his moral Exodus; the souls of the saved are making their final journey of Exodus from earth to Paradise.8

The delivering angel retreated as quickly as he had come; the souls, entered into this new world, would be “spurred by their desire for justice” to eagerly begin their climb, just as those souls clamoring for Charon’s boat in the Underworld were eager.

The sun had risen higher, as Apollo the Archer chased Capricorn further from the sky’s meridian, and the newly arrived souls ask of Dante and Virgil the way that they should go, thinking they they were also souls newly entered into this land.

“You may be convinced

that we are quite familiar with this shore;

but we are strangers here, just as you are;

we came but now, a little while before you,

though by another path, so difficult

and dense that this ascent seems sport to us.”

ii.61-66

Upon realizing that Dante was a living, breathing person, the souls crowded round him, eager to see him, in our first Homeric simile of Purgatory:

Just as people crowd around a messenger

who bears an olive branch, to hear his news,

and no one hesitates to join that crush,

so here those happy spirits - all of them -

stared hard at my face, just as if they had

forgotten to proceed to their perfection.

Ii.70-75

One soul comes forward to embrace Dante, who, in attempting to return the embrace, finds that his arms pass through the incorporeal soul; three times Dante tried, in the same way that Aeneas, in the Underworld of Virgil’s Aeneid, tries to embrace his father upon finding him in the blessed land of the Elysian fields:

“So, father,

Give me your hand! Give it, don’t pull away as I hug and embrace you!”

Waves of tears washed over his cheeks as he spoke in frustration:

Three attempts made to encircle his father’s neck with his outstretched

Arms yielded three utter failures. The image eluded his grasping

Hands like the puff of a breeze, as a dream flits away from a dreamer.

Aeneid vi.697-102

Only when the soul spoke did Dante realize who it was; his friend from earth, Casella the musician.

This was Casella da Pistoia, a great musician, especially in the art of setting words to music. He was very well acquainted with the author, who in his youth wrote many songs and ballads, which Casella set to music. Dante took great delight in hearing him sing them.9

Dante mentions again that he is eager to return to this place one day (as he did in line 16), indicating that he sees the state of his soul as worthy of this placement in Purgatory, and wonders why Casella is only at that moment arriving, as it seems he had died some time before.

Casella tells him that the ministering angel chooses who can sail and had for a time not chosen him, with the implication that all will be brought in time; the angel’s choices are guided by the “Just Will” of God. However, with the timing of the Jubilee of Pope Boniface VIII and the broad swath of indulgences granted, it seems that all are now able to cross much more quickly.

From whence those bound for Purgatory come is identified as the source of the Tiber river outside of Rome; the meeting place for those bound for Hell is not so identified. Dante asks Casella for a balm to his weary soul — which is still newly out of Hell — and asks him to sing a song for him if it be allowed under the laws of Purgatory, which Dante is yet to familiarize himself with. Casella opens with a line from Dante’s own poetry:10

“Love that discourses to me in my mind”

he then began to sing - and sang so sweetly

that I still hear that sweetness sound in me.

My master, I, and all that company

around the singer seemed so satisfied,

as if no other thing might touch our minds.

ii.112-117

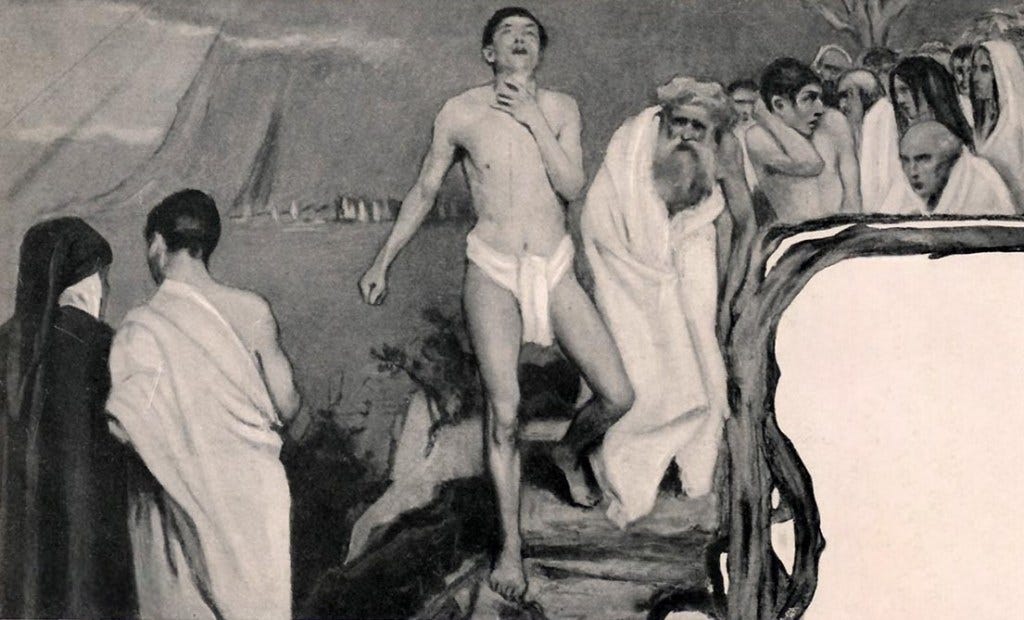

As beautiful and soothing as this music is, however, it is keeping the souls who listen, entranced, from their greater purpose; a purpose that has no place for lingering. Cato, the guardian of Purgatory, arrives to rebuke and scold those who would stand listening to something of earth rather than moving forward with the cleansing of Purgatory.

What have we here, you laggard spirits?

What negligence, what lingering is this?

Quick, to the mountain to cast off the slough

that will not let you see God show Himself!”

ii.120-123

This idea of ‘slough’ is anything of the earthly body that covers the illumination of the cleansed soul; as a snake shedding an old skin, it is more than a filth to be washed away as was the stain of Hell on Dante’s face; it is a removal of that which encrusts the shining soul within.

How then, can you see the kind of beauty that a good soul has? Go back into yourself and look. If you do not yet see yourself as beautiful, then be like a sculptor who, making a statue that is supposed to be beautiful, removes a part here and polishes a part there so that he makes the latter smooth and the former just right until he has given the statue a beautiful face. In the same way, you should remove superfluities and straighten things that are crooked, work on the things that are dark, making them bright, and do not stop ‘working on your statue’ until the divine splendour of virtue shines in you, until you see ‘Self-Control enthroned on the holy seat.’

Plotinus Enneads I.6.9.5-15

The souls, thus scolded, scatter like doves in another Homeric simile, away from the music and from Dante, seeking the way to a path up the mountain. Dante and Virgil follow just as quickly.

💭 Philosophical Exercises

As far as possible, join faith to reason.

~ Boethius

‘To make it easier for him, I will wipe a little of the blinding cloud of worldly concern from his eyes.’

These are the words of Lady Philosophy, spoken to Boethius as he sat alone in his dark prison cell, awaiting execution. Blinded by the Furies - those evil spirits who sang to him a sweet but delusive song, he is momentarily consoled by a false and fleeting comfort. Their song lures him to forget the great Lady who had served him so faithfully, the one who alone could offer true peace, true consolation, if only he would wipe the worldly dust from his eyes.

When Boethius wipes his ‘worldly tears’, as Dante did at the end of the previous canto, she proceeds with another beautiful piece of wisdom:

This is hardly the first time that wisdom has been threatened with danger by the forces of evil.

But let us be fair to Boethius, his work is too beautiful and meaningful, that I feel it awfully unjust to quote him; we must read his work with the same intensity as we read Dante now.

We find our pilgrims cleansed from the tears of Inferno and Dante tells us about the stars, the stars that we can see in this realm, his description is beautiful and tells us about the world above as well as about the world below.

If the previous canto was all about the planet Venus that represents Love, this canto is dedicated to Mars. Each part of the Seven Liberal Arts (Grammar, Logic, Rhetoric, Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy) in Dante’s Convivio was associated with a planet, and Mars was associated with Music.

I want to remind my reader that the descent into Hell and into self-destruction is easy. Its gates are wide open, welcoming at all times. It is the ascent, the journey our pilgrims now undertake, that demands true effort. Michelangelo could have shattered his massive block of marble in an instant, but carving it into an angel, shaping it into beauty, required patience, vision, and mastery.

If Inferno was harrowing for its horrors, Purgatorio is demanding in a different way: here we must shed our vices, our excesses, to ascend toward what now appears to be inscrutable heights. Ascent is always more difficult than descent.

Here, we witness Dante experience a moment of hesitation; one that mirrors, yet differs from, the doubt he expressed in the second canto of Inferno. There, he confesses: “I annulled the task I had so quickly undertaken” (lines 37–41). In the Inferno, Dante’s hesitation stemmed from self-doubt.

But there are dangers that are much greater than self-doubt and they are distraction and false consolation. These can lead us astray more subtly, yet more perilously, for they disguise themselves as comfort, pulling us away from the path without resistance.

Dante’s mind is fixed upon the planet Mars at this point of our journey, which is located in the west, meaning that his back is turned to the east where the sun and true transformation flows. Dante’s spirit, in other words, focuses on Music instead of following the true path.

We still were by the sea, like those who think

about the journey they will undertake,

who go in heart but in the body stay.(lines 10-12)

This is the evil of distraction and false consolation, this is what furies did to Boethius, they made his heart go but his body stay. The simile in the lines 10-12 might sound familiar to my reader, we have heard them before…

I. How Our Dreams Die in the silence of our Imagination

And just as he who, with exhausted breath,

having escaped from sea to shore, turns back

to watch the dangerous waters he has quit,so did my spirit, still a fugitive,

turn back to look intently at the pass

that never has let any man survive.(Inferno I, lines 22-27)

In Inferno, the simile was of a man who, with exhausted breath, had just escaped the deadly embrace of the sea and looked back at what nearly dragged him into the abyss. In Purgatorio, the simile shifts: the man has escaped the sea and now looks forward to the journey ahead but only imagines it. He does not yet undertake it.

How often do we do the same, my reader?

We imagine the journeys we could have taken, the lives we might have lived, if only we had dared to set foot on the path. And so, our potential self dies not in action, but in the silence of our own imagination. They say there is no encounter more painful than meeting the person you could have become, if only you had acted.

II.

Soon, we witness a group of souls disembarking on the shore, delivered by a heavenly figure, whom we will briefly explore in the Themes section. What is curious is that Virgil, our reason, is almost completely silent in this canto, the only words he utters are:

“Bend, bend your knees: behold the angel

of God, and join your hands; from this point on,

this is the kind of minister you’ll meet.

What does Dante the writer try to convey through this nuance?

The Russian philosopher Nicholas Berdyaev, writing in the early 20th century, observed that reason is only one way through which we perceive, attend to, and comprehend the world. In the philosopher’s view, we perceive the world through experience, religious feeling, and the inner freedom of the spirit—not merely through rational analysis. For Berdyaev, true knowledge arises not from detached objectivity, but from a personal, existential engagement with truth that transforms the knower in the process.

This scene reflects Berdyaev’s insight. Here, Virgil - Reason - tells us to bow before something greater than ourselves, something that lies beyond our comprehension.

It is worth reminding that Virgil remains silent when Dante becomes distracted and indulges in the beautiful song flowing from Casella’s lips. It is another figure who puts Dante back to the righteous path…

III.

‘Who’, she demanded, her piercing eyes a light with fire, ‘has allowed these hysterical sluts to approach this sick man's bedside?

‘They have no medicine to ease his pains, only sweetened poisons to make them worse. These are the very creatures who slay the rich and fruitful harvest of Reason with the barren thorns of passion. They habituate men to their sickness of mind instead of curing them.’

~ The Lady Philosophy in Boethius’s The Consolation of Philosophy

There can be nothing more dangerous to our dreams and goals we want to achieve than the seductive powers of comfort. The ascent, the sculpting of our better selves, depends on the intensity of our dreams and strength our will. Comfort kills them both. For when Dante meets his friend Casella here he asks:

And I: “If there’s no new law that denies

you memory or practice of the songs

of love that used to quiet all my longings,then may it please you with those songs to solace

my soul somewhat; for—having journeyed here

together with my body—it is weary.”(lines 106-111)

The song that Casella sings is to the Lady Philosophy, which, as Hollander notes, comes from Dante’s own work, Convivio. Once again, we see the unmistakable footprints of Boethius in Dante’s thought. A modern parallel to this scene might be you or I watching inspirational self-help videos on YouTube—feeling moved, yet doing nothing to truly transform our lives.

Where is Virgil here? Where is our guide, our Reason, to wake us up from this trance?

He is quiet. Perhaps also seduced by the sweet song of Casella. After all our reason easily confuses what we see in imagination from reality.

It is Cato who comes to Dante’s ‘rescue’ by calling those who listen ‘laggard spirits’, who ‘linger’ instead of beginning their ascent.

I found this profoundly moving, as it reveals the darker recesses of our psyche. We often grow weary and fatigued, like Dante, in whatever pilgrimage we choose to undertake. Ascent is difficult, and far too often we substitute the real progress we might make with escapism—retreating into a world of shadows and distractions.

Those who escape Inferno often believe the hardest part is behind them, unaware that descending into the depths of Hell is far easier than ascending the heights of virtue.

Final Thoughts 💭

We have covered a great deal in this section, and I would like to close it with the words of Saint Paul: “Put off the old man, and put on the new.”

In the Christian vision, life is ultimately a pilgrimage. There are, of course, pilgrimages to sacred sites, these are physical journeys, journeys of the body, but there are also pilgrimages of the spirit, of the soul, of the conscience. The physical pilgrimage has value only if it brings the essence of one’s being closer to virtue.

One person might gaze at Botticelli’s Venus on a computer screen and undergo a deep spiritual transformation. Another might stand before the very same painting in the Uffizi in Florence and remain utterly unmoved.

This is precisely what we witness with Dante and the other souls in this scene. They are in Purgatory, they have been granted the chance to cleanse their vision and move toward the highest good and yet they choose escapism, a substitution in the form of music.

This Week’s Sinners and Virtuous 🎭

(Themes, Quotes, Terms and Characters)

Intensity of pilgrimage

There are so many themes in this canto I long to include, and I can hardly forgive myself each time I press delete. But one I cannot leave behind is the theme of intensity or the burning focus with which one must approach the path to virtue.

The journey toward greatness is not measured by distance but by depth. It is not how far we go, but how deeply we draw from the well of our own spirit. The heights we may reach (those inscrutable heights of moral or spiritual excellence) depend on how much inner fire, how much fervour, we bring to the task.

To cultivate virtue is not to tread a gentle path, but to will ourselves again and again into concentration, presence, and purpose.

Angel with no oars

See how much scorn he has for human means;

he’d have no other sail than his own wings

and use no oar between such distant shores.(31-33)

In contrast to Ulysses who made oars his wings, substituted his spirit to technology, this heavenly angel has no oars, and his boat was ‘not swallowed by the water’.

If Inferno had guardian demons, Purgatory has guardian angels.

Dante’s embrace

Dante embraces Casella even before he recognises him. I found Hollander’s remark on this quite interesting, that Dante, after crossing the Inferno, became more open and kind here. He notes that this is an example of display of ‘Christian affection’.

Those who are aimed for Purgatory

From Dante’s description, we learn that Casella had been dead for some time, and if we align the dates, it appears he enters Purgatory three months after his death. Some commentators have noted that the souls destined for Inferno go there immediately, while those bound for Purgatory must wait to be chosen and prepared before being allowed to enter this new realm. In Casella’s case, it appears he was permitted to board the angelic boat only three months after his death.

Barbara Reynolds, in her commentary, speculates that Casella may have spent his life singing unworthy songs and that it was his friendship with Dante that ultimately saved him.

Music in Purgatory

My reader might remember that in Inferno we had a perverted forms of music, embodied by the corrupt politicians. I would like to note that from now on music will become more and more angelic. Once again, for a deep thinker, especially like Dante, nothing is black or white, music can be devilish and distracting, but also healing and helpful.

For those who would like to revisit that part 👇

Quotes 🖋️

(The ones I keep in my journal as reminders of eternal wisdom):

Don’t we all need Cato in our lives? There verses hit my particularly strongly reading Purgatory this time with all of you. I have marked the lines that I find exceptionally touching with bold.

We were spellbound, listening to his notes,

When the vet vulnerable old man appeared and cried:

‘What is this, laggard spirits?

‘What carelessness, what delay is this?

Hurry to the mountain and there shed the slough

That lets not God be known to you.

(Hollander’s translation of the last lines of Purgatorio)

Inferno xxvi.106-11

Charles S. Singleton, Commentary on Purgatorio 26

Inferno ix.85-90

Singleton 30

Jean & Robert Hollander Purgatorio 40

“This exposition has to be both literal and allegorical. To better comprehend this, it should be understood that written works can be comprehended and explained in terms of four main senses.

The first is called literal; this is the one that [does not go beyond the letter of the fictitious words, since they are the fables of the poets].

The second is called allegorical, and this is the one hidden under the mantle of these fables; it is a truth concealed beneath a beautiful lie…

The third sense is called moral; this is the one that teachers must intently hunt down in written words, for their own and their students’ benefit…

The fourth sense is called anagogical, that is, supersensible. This is when a passage of writing is interpreted spiritually, which, while still true in the literal sense, through the things denoted denotes the celestial things of eternal glory, as one can see in the song of the Prophet which says that in the exodus of the people of Israel from Egypt, Judea is made holy and free. Although plainly true in terms of the letter, no less true is the spiritual sense: that in its exodus from sin the soul is made holy and free in its power.”

Dante, Convivio II.i.1-7, condensed, translated by Andrew Frisardi.

Singleton 31

Mandelbaum 630-31

Singleton 36

Dante Convivio III.i

This canto felt so dense. I read it multiple times in 2 translations. I need the help of Mandelbaum's footnotes, but am drawn to Musa's wording and spacing of these cantos. I appreciate your writing and my familiarity with the sections you include is helpful.